Elements of Rhetoric PowerPoint

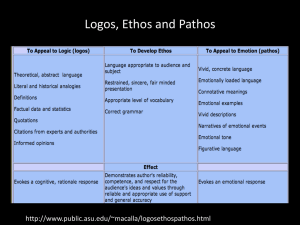

advertisement

Using the “Available means” “The faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” Aristotle What is persuasion? Sometimes rhetoric has a negative connotation and suggests deception; but for our purposes of study we will not label rhetoric as such. “At its best, rhetoric is a thoughtful, reflective activity leading to effective communication, including rational exchange of opposing viewpoints.” What does it mean to be thoughtful? What does it mean to be reflective? What is effective communication? What does it mean to be rational? Those who understand and can effectively use the means to appeal to an audience gain power. Those who understand and can effectively use the means to appeal to an audience can resolve conflicts peacefully or without confrontation. Those who understand and can effectively use the means to appeal to an audience can persuade readers and/or listeners to support their position on an issue. Those who understand and can effectively use the means to appeal to an audience can move others to action. 1. It is always situational and has context. The occasion (what is happening at that moment) or the time (think time period) and place is always considered by the writer or speaker. 2. It always has a purpose or goal that the speaker or writer wants to achieve. Win an argument? Persuade the audience to take action? Evoke sympathy? Make someone laugh? Inform the audience of an important issue? Provoke emotion? Celebrate an important occasion? Repudiate (reject as having no authority or binding force) a claim? Put forth a proposal? Secure support for an initiative? Bring about a favorable decision? Sometimes the context arises from current events or bias, a tendency that prevents unprejudiced consideration of an issue. Ex: writing about freedom of speech in a community where graffiti has run rampant must be considered. That context forces the writer to adjust the purpose of the piece so as not to offend the audience. Aristotelian Triangle Speaker/ Writer Audience/ Reader Subject/ Subject There is an interaction among the subject, speaker, and audience that must be considered for rhetoric to be effective. This interaction determines the structure and language of the argument. Skilled writers consider the interaction among speaker, subject, and audience as they are developing whatever it is they are writing. 1. Choose a subject and then evaluate what they already know about it, what others have said about it, and what kind of evidence will sufficiently develop their position. 2. Consider the audience. What does the audience know about the subject? What is the audience’s attitude about the subject? Is there common ground between my views (the writer) and the audience’s views on the subject? 3. Are aware of the persona assumed when writing. That is the character created when the writer writes. Poet? Expert? Comedian? Scholar? Critic? 4. Each audience requires use of different information to craft the argument effectively. In order to persuade the audience, writers make strategic choices by appealing to ethos, logos, pathos. Ethos: an appeal to character, credibility, trustworthiness Logos: an appeal to logic or reason Pathos: an appeal to emotion In order to demonstrate they are credible and trustworthy, speakers and writers appeal to ethos. The ethos of the speaker includes expertise, knowledge, experience, training, sincerity. Appeals to ethos often emphasize shared values between the speaker and the audience Sometimes, a speaker’s reputation immediately establishes ethos. Sometimes, ethos is established through the exchange between listener and speaker by making a good impression. An appeal to logos is an appeal to reason or logic. That is offering clear, rational ideas. When you appeal to logos, you have a clear main idea (thesis) with specific details, examples, facts, statistical data, or expert testimony as support. Another way to appeal to logos is to acknowledge a counterargument by anticipating objections or opposing views. Don’t worry about weakening your argument by discussing the opposing view; most likely, you will create an even stronger logical appeal by demonstrating your careful consideration of the subject. Sometimes in a logical appeal, you will concede (agree) or make a concession. That is you agree that an opposing argument may be true, but then you work to prove why that argument is not valid. When you refute (deny), you provide evidence that actually strengthens your argument by disproving the opposing view. (refutation) Pathos is an emotional appeal. Writing that relies strictly on pathos is rarely effective in the long term. It can become propagandistic in purpose; more polemical than persuasive. However, using language (figurative, anecdotal) that engages the emotions of the audience can add an important dimension to the argument. Choosing words with strong connotations (positive or negative) evoke emotion. Imagery is another language technique that evokes pathos. Logos: logic Ethos: credibility Pathos: emotion Let’s examine Lou Gehrig’s July 4, 1939, farewell speech for its rhetorical qualities. Context (occasion, time, place) Purpose (goal) Thesis Subject Audience Speaker Persona Ethos Logos Pathos Read pages 6 – 8. Complete the graphic organizer by identifying where the specific appeals have been used and were effective in Heyman’s article. Ethos Logos Pathos Read pages 9-10 and complete the graphic organizer below. This is the organization of the piece of writing. Why is it important to consider how the essay and its individual paragraphs or sections are arranged? We must ask ourselves “Is the text organized in the best possible way in order to achieve its purpose?” We know that an essay always has a beginning, a middle, and an end: the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. But how a writer structures the argument within that framework depends upon his or her intended purpose and intended effect. This is a five part structure for an oratory, or speech that writers use today, although perhaps not always consciously. 1. The introduction (exordium) 2. The narration (narratio) 3. The confirmation (confirmatio) 4. The refutation (refutatio) 5. The conclusion (peroratio) Introduces the reader to the subject under discussion In Latin, “exordium” means “beginning a web”. Why so aptly named? Can be a single paragraph or several that draws the readers into the text by piquing their interest or challenging them Often it is in the introduction that the writer establishes ethos. Why is this important? Provides factual information and background material on the subject. Establishes why the subject is a problem that needs addressing. The level of detail included in this section is largely dependent upon the audience’s knowledge of the subject. It is in this section that the writer often appeals to pathos, as an attempt to evoke an emotional response about the importance of the issue being discussed is made. This is usually the major part of the text. Includes the development or the proof needed to make the writer’s case. Here the most specific and and concrete detail is concluded. This section generally makes the strongest appeal to logos. Why? This section addresses the counterargument. This is seen in many ways as a bridge between the writer’s proof and conclusion. This is often placed at the end of the text as a way to anticipate objections to the proof given in the confirmation section. However, that is not always the case, dependent upon the audience being addressed. If opposing views are well known or valued by the audience, then the writer may want to address them before presenting his or her own argument. This section is largely appealing to logos. Can be one paragraph or several. Brings the essay to a satisfying close. There is usually an appeal to pathos and a reminder of the ethos established earlier. Instead of just repeating what has been said before, this section brings all the writer’s ideas together and answers the question, “So what?” Writers should remember that the last words of a text are those the audience is most likely to remember. Begin thinking about a research paper topic regarding a contemporary issue that is worthy of debate. Next Friday, you will be asked to submit a topic for approval along with a brief description of the issue and why it is worthy of research. Some ideas to begin sparking your research ideas: Global warming The Afghanistan War The student loan debt crisis Changing weather patterns The same elements of rhetoric are at work in visual texts like political cartoons. Political cartoons are often satirical, using wit to make a point, or critical, using evaluative judgments to state a position. However, sometimes they are neither as evidenced in the Rosa Parks cartoon by famous Washington Post political cartoonist Tom Toles. http://www.larsonsworld.com/blog/archives/cat_1064569116.html Ethos Logos Pathos http://thecomicnews.com/images/edtoons/2012/0314/gop/01.jpg