Susan Dicklitch Powerpoint

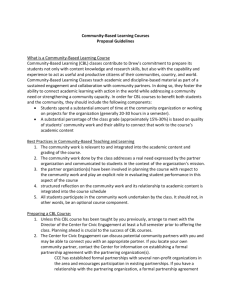

advertisement

Empowering Students and Faculty Through Communitybased Learning…..and making a real difference in the world Spring 2011 Dr. Susan Dicklitch Franklin & Marshall College What is Community-Based Learning? CBL/Service-Learning Pedagogy Community-based learning deliberately integrates community service activities with educational objectives CBL is NOT the equivalent of Voluntarism CBL fills a real need in the community– students perform a valuable, significant, and necessary service which has real consequences to the community (Robert Bringle and Julie Hatcher, “Reflection in Service-Learning: Making Meaning of Experience”, Educational Horizons. Summer 1999, pp. 179-185). Questions for Faculty Utilizing CBL What do you want your students to get out of the CBL experience? How does the CBL component tie in to your course objectives? How will those outcomes be supported by course activities, readings & assignments? How will the CBL experience factor into your evaluation of the students’ learning? The 3 R’s of Community-Based Learning: Rigor Reflection Reciprocity RIGOR High Quality CBL courses successfully blend academic rigor with Community Service REFLECTION Reflection is the bridge between experience and theory (Robert Bringle and Julie Hatcher, “Reflection in Service-Learning: Making Meaning of Experience”, Educational Horizons. Summer 1999, pp. 179-185). RECIPROCITY THE STUDENT LEARNS FROM THE COMMUNITY & THE COMMUNITY BENEFITS/LEARNS FROM THE STUDENT SERVICE Human Rights-Human Wrongs WHY? Africanist by training No knowledge of U.S. asylum law Asked to be an expert witness on a Ugandan asylum case Powerful, real-life experience – wanted to give students that same experience HR-HWs First taught HR-HW in 2002 Senior seminar level Students not expected to have any previous legal training Students are taught about asylum law & human rights in general 5 hour legal-training workshop by community partner HR-HW WHAT? Students work in teams of 2 on real political asylum cases Interview asylum seeker – story of persecution: Affidavit Conduct country-conditions research: Evidentiary Packet Examine case law: Legal Brief/Legal Memo Reflect on experience: Reflection Journal HR-HW HOW? Found a community partner (PIRC -- local NGO) that works with asylum seekers York County Prison – ½ hour away from F&M in York County, (maximum-security prison) Houses about 800 detained immigrants (not all asylum seekers) Community Need? Asylum seekers are not provided counsel by the government Only get legal counsel if they can afford it, or if they are lucky enough -- a pro-bono attorney In 2010, only 43% of “aliens” that went before an immigration judge were represented Making a Real Difference? Students worked on 57 political asylum cases from 2002- 2010 Asylum seekers came from 31 different countries 21 positive outcomes (asylum, withholding of removal, or CAT relief) – 35% grant rate The grant rate for affirmative cases = 61% The grant rate for defensive cases = 35% (EOIR 2010 Stats) Empowering Students? At the beginning of this course, I did not know much about immigration law. I did not know anything about asylum or withholding of removal. At the beginning of this course, I did not think I was interested in being a lawyer or that there were careers in law that could really make such a positive impact on the lives of the suffering. I did not think that working on the case and listening to my client’s story would my me feel physically ill and would keep me up at night. But, then again, I did not know that I would feel this passionate about a cause and that the overwhelming feeling of work combined with the pressure to put together a good case would actually produce one of the most rewarding feelings that I’ve ever felt from a class. At the beginning of this course, I did not know what this course would actually mean to me. Now, I realize that it means first hand knowledge and experience in an issue that I will never forget because I lived through it. It means a greater understanding of what is happening around the globe along with how that affects what is happening in the United States. It means understanding of the asylum law process, its shortfalls, its strengths and potentially how it could be reformed. And it means seeing judges and ICE attorneys as people instead of as the heartless robots that they can sometimes appear to be from the applicants’ perspective. All of this together means that I am more of a global citizen than ever with knowledge of how we are all interrelated (GG, HR-HW, 2009). “Yesterday, I went to meet KL at York County Prison. It was one of the most visceral experiences of my life. She is 21 years old and already has two children. She is only two years older than me. As I heard her story, the harsh reality of what goes on during war became clear to me. I have never had to experience war first hand. I have seen it on television, read about it in books, but I have never sat face to face with someone who had witnessed the wrath of war like KL has”. (AM, HR-HW, 2007) Why Successful? Addresses a real community need Engages students in a real-world issue/problem It’s up-close-and-personal Real partnership between our community partner (PIRC) & the students/faculty Continued faculty/research/engagement Challenges: CBL courses are labor intensive/logistically challenging CBL courses can also be more costly than regular, traditional courses Tenure/promotion systems often do not value “pedagogy” over research Often difficult to find meaningful and intensive CBL experiences for both students and community partners (reciprocity) – find out what the needs are of your community Suggestions: Quality over quantity Need administrative/institutional support Develop faculty (paid) workshops (summer or during semester) Don’t be afraid to try! “Take Aways”: CLB is a valid academic pedagogy (it is not simply glorified voluntarism) If done correctly, it challenges students cognitively, and affectively – the unique blend of cognitive and affective learning often makes a lasting impression on students You can do it! EOIR, 2010) PART II: Five Models of CBL 1) Discipline-Based CBL Students are expected to serve in the community throughout the semester & to reflect on their experiences on a regular basis using course content as a basis for analysis and understanding 2. Problem-Based CBL Students (or teams of students) relate to the community as “consultants” working for a “client” Presumes that students will have some knowledge they can draw upon to make recommendations to the community 3. Capstone Courses Generally designed for majors & minors in a given discipline Usually senior level Draw on knowledge students obtained throughout their coursework & combine it with relevant service work in the community 4. CBL Internships Like traditional internships, more intense than typical CBL courses with students working as many as 10-20 hours a week in a community setting Students charged with producing a body of work that is of value to the community Unlike regular internships -- have regular & on-going reflective opportunities that help students analyze their new experiences using discipline-based theories 5) Undergraduate CommunityBased Action Research Students work closely with faculty members to learn research methodology while serving as advocates for communities Like an independent study option (Excerpted from: Kerrissa Heffernan, Fundamental of Service-Learning Course Construction. RI: Campus Compact, 2001, pp. 2-7.). What are the Learning Objectives of CBL? To engage students in learning outside of the academic classroom – for the rest of their lives they are going to be in that community Hands-on practical experience (boards, service clubs, interacting with school districts etc.,) Knowledge with application helping students to actualize the tools that are needed to navigate the world (part cognitive, part affective), e.g., Mission Statement of the College The Do’s of CBL Pedagogy Academic credit is for learning, not for service Do not compromise academic rigor Set learning goals for students Establish criteria for the selection of community service placements Lay out your learning strategies Prepare students for learning from the community Minimize the distinction between the students’ community learning role & classroom learning role RELAX!!!! (be prepared for loss of control) Howard J. (1993) Community Service learning in the curriculum, in J. Howard (ed) Praxis I: A faculty casebook on community service learning,(Ann Arbor, MI: OCSL Press) pp. 3-12.