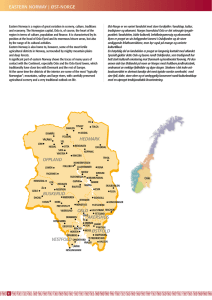

Sven Ivar Dysthe: Swinging 60 - Norsk designpioner

advertisement

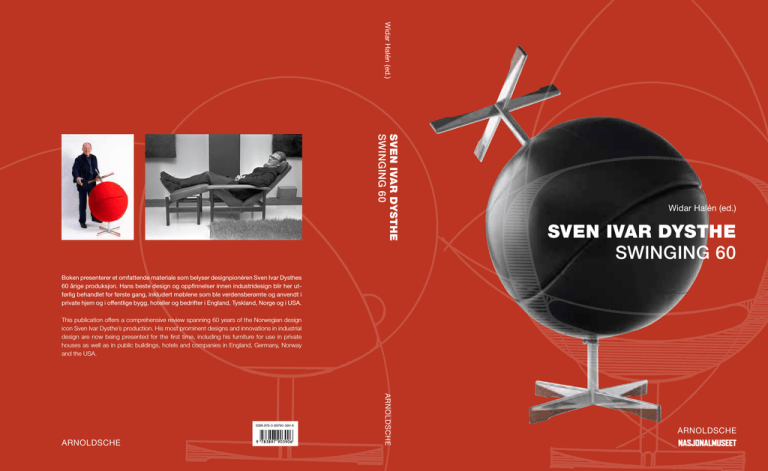

Widar Halén (ed.) SVEN IVAR DYSTHE Swinging 60 Widar Halén (ed.) SVEN IVAR DYSTHE Swinging 60 Boken presenterer et omfattende materiale som belyser designpionéren Sven Ivar ­Dysthes 60 årige produksjon. Hans beste design og oppfinnelser innen industridesign blir her utførlig behandlet for første gang, inkludert møblene som ble verdensberømte og anvendt i private hjem og i offentlige bygg, hoteller og bedrifter i England, Tyskland, Norge og i USA. This publication offers a comprehensive review spanning 60 years of the Norwegian design icon Sven Ivar Dysthe’s production. His most prominent designs and innovations in industrial design are now being presented for the first time, including his furniture for use in private houses as well as in public buildings, hotels and companies in England, Germany, Norway and the USA. ARNOLDSCHE Dysthe Arnoldsche ARNOLDSCHE ISBN 978-3-89790-390-6 ARNOLDSCHE SVEN IVAR DYSTHE Swinging 60 Trinelise Dysthe Thomas Flor Widar Halén ARNOLDSCHE Art Publishers Forord Foreword Dysthe Design – Swinging 60, hyller Sven Ivar Dysthes 60 årige karriere, som en av våre mest markante designere i etterkrigstiden. Sven Ivar Dysthe (f. 1931) er en av våre få internasjonalt utdannete designere, med masteroppgave i industridesign fra det prestisjetunge Royal College of Art i London i 1954. Dysthe kom som et friskt pust inn i det norske designmiljøet. Han har vært med å plassere Norge på kartet i en tid da vi fikk lite oppmerksomhet utenlands. Norsk design og norske møbler har ofte vært kritisert for å være for ”norske”, i betydningen tunge, klumpete og husmannsaktige. Dysthe var med sine internasjonale vyer med på å endre dette bildet. Han lanserte en stil som var norsk, men med tydelige internasjonale referanser. Dette sees best i hans møbelmodeller, som hele livet har vært hans største virkefelt, og hvor han som få andre har preget vårt daglige miljø i Norge. Som industridesigner har Dysthe tegnet en lang rekke produkter – reoler, kjøkkeninnredninger, hyttemøbelsystemer, skibindinger, trykkluftkompressor og ulike lamper med mer. Da han fikk Jacob-prisen i 1989 roste juryen hans evne til å gjennomarbeide et produkt til minste detalj, og til å finne enkle løsninger på kompliserte problemer. Dysthes formuttrykk er elegant, internasjonalt og ukunstlet, og han har gitt et grunnleggende bidrag til å utvikle norsk design i internasjonal retning, og til å plassere Norge på det store designkartet. Det er med stor glede Nasjonalmuseet gir en bred og systematisk presentasjon av Sven Ivar Dysthes verk i form av ustilling og bok. En stor takk til Sven Ivar Dysthe og til forfatterne Trinelise Dysthe, Thomas Flor og Widar Halén, samt til bokens sponsor Stiftelsen Scheibler og til Arnoldsche Art Publishers. Dysthe Design – Swinging 60 pays homage to Sven Ivar Dysthe’s sixty-year career as one of our most celebrated designers in the post-war period. Sven Ivar Dysthe (b. 1931) is one of Norway’s few internationally trained designers, having graduated in 1954 with a masters degree in industrial design from the prestigious Royal College of Art in London. Dysthe brought a breath of fresh air into the world of Norwegian design. He helped to put Norway on the map at a time when we were receiving little international attention. Norwegian design and Norwegian furniture have often been criticised for being too “Norwegian”, meaning heavy, cumbersome and provincial. With irresistable ambition, Dysthe helped to change this image. He launched a style that was still Norwegian, but had clear international references. This is best seen in his furniture designs, the field in which he has always been most active – designs with which he transformed the daily environments of ordinary Norwegians like no one else. As an industrial designer Dysthe has been responsible for a wide range of products – shelving systems, kitchen units, chalet furniture, ski bindings, industrial compressors, domestic lamps of various kinds, and much more. When he was awarded the Jacob Prize in 1989 for his life’s work, the jury praised his ability to refine a product to the minutest detail and to find simple solutions to complex problems. With a style that is elegant, international and unpretentious, Dysthe has made a fundamental contribution to making Norwegian design more internationally viable, helping to put Norway on the map of design interests worldwide. It is with great joy that the National Museum presents this broad and systematic review of Sven Ivar Dysthe’s work to coincide with its major exhibition of the designer’s work. We owe a debt of gratitude to Sven Ivar Dysthe and the authors Trinelise Dysthe, Thomas Flor and Widar Halén. Our thanks are also due to the sponsor of this publication, Stiftelsen Scheibler and to Arnoldsche Art Publishers. Audun Eckhoff, Direktør Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design 1 Detalj av svingstolunderstell til 3001-seriens første ”sjefstol”. Dokka Møbler, 1962. Detail of the swivel base of the first 3001 “Executive Chair”. Dokka Møbler, 1962. Audun Eckhoff, Director The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design 7 8 9 10 Svennestykket APPRENTICE PIECE Av Trinelise Dysthe Trinelise Dysthe 11 Svennestykket APPRENTICE PIECE Møbelsnekker Cabinetmaker ”Jeg vil bli snekker”, utbrøt femåringen. Han hadde fått høvelbenk av morfaren som hadde vurdert håndlaget til gutten. ”Jeg vil bli snekker. Møbelsnekker!” gjentok han da han hadde fullført 8 klasse. Han trivdes ikke på skolebenken, men sløydtimene hadde gitt ham mestringsfølelsen og selvtilliten tilbake. Men faren ble skuffet. Han hadde bygget opp en agenturforretning, og hadde nok sett for seg at sønnen skulle følge i samme fotspor. Men han kom ham i møte, og gjennom en bekjent fikk han skaffet ham en læringsplass hos en av de mest anerkjente snekkerverkstedene i Trondheim. Etter tredje året var Sven Ivar klar til å ta sin svenneprøve. ”Du er for ung. Det er for tidlig”, mente mesteren, men Sven Ivar sto på sitt. Han hadde ikke fått kontrakt, og visste at han hadde rett til å ta prøven etter tredje året. ”Du kan nok saktens få til et svennestykke, men du vil ikke klare å mestre en stor og vanskelig oppgave.” Mesteren var fortsatt ubøyelig. ”Da velger jeg å lage en vanskelig oppgave”, repliserte Sven Ivar. I mellomtiden hadde familien flyttet til Bærum kommune hvor snekkermester Reidar Hansen drev et velrenommert verksted på Skui. Faren tok “I want to be a carpenter,” exclaimed the five-yearold. Impressed by the youngster’s manual dexterity, his grandfather had given him a carpenter’s bench. “I want to be a carpenter. A cabinetmaker!” he repeated after finishing his fourth form. He had not been comfortable in school, but woodworking classes had filled him with confidence and belief in his own skill. Even so, his father was disappointed. He had built up an agency business, which he was probably hoping his son would take over. But the youngster had different ideas, and with the help of an acquaintance his father managed to find an apprenticeship at one of Trondheim’s most reputable carpentry workshops. After three years, Sven Ivar was ready to take his apprentice’s exam. “You’re too young. It’s too early,” the master craftsman said, but Sven Ivar was insistent. Having not signed a contract, he knew that he was entitled to take the exam after three years. “I dare say you could make an apprentice piece, but you wouldn’t be able to cope with a large and difficult task.” The master was still adamant. “In that case I choose to take on a difficult task,” replied Sven Ivar. page XXX: 2 System Dysthe hyllesystem, kalket eik eller teak. Gjøvik Møbler, 1959. System Dysthe, shelf system in limed oak or teak. Gjøvik Møbler, 1959. 3 Etter svenneprøven ville Sven Ivar Dysthe utdanne seg til designer. Faren støttet hans yrkesvalg. After finishing his apprentice piece, Sven Ivar Dysthe wanted to train as a designer. His father supported his choice of profession. kontakt, og Sven Ivar kunne dra hjem og stå hos ham og fullføre svenneprøven. I løpet av året tegnet og snekret han en gedigen herrekommode i mahogni med avrundete dører, innvendige sinkete skuffer, sjalusitrekk, spesialinnredning til konvolutter og brevpapir i A4-format, oppheng til skjorter og bukser, skuffer til undertøy og sokker, ventilert skoskuff og til og med et flaskerom til en styrkedrikk eller to som det seg hør og bør for en herre av datidens gode selskap. (fig. 3) I 1951 ble ”vågestykket” og ferdighetene til den unge snekkeren vurdert av Håndverklaugets jury, og sto til særdeles i alle disipliner. Nye valg 3 Svennestykke, en innholdsrik herrekommode i mahogni fra 1951. Apprentice piece, a comprehensive master dresser in mahogany from 1951. 12 Etter endt militærtjeneste i 1952 var den unge snekkersvennen klar for å prøve seg på arbeidsmarkedet som fullbefaren møbelsnekker, men var det fremdeles dette han ville? I tre år hadde han arbeidet etter andres tegninger. Nå ville han noe Meanwhile, the family had moved to the municipality of Bærum near Oslo, where master carpenter Reidar Hansen ran a highly respected workshop at Skui. Sven Ivar’s father got in touch with Hansen and negotiated an opportunity for his son to make his apprentice piece in this local workshop. In the course of a year, Sven Ivar designed and crafted a huge master dresser, which he made in mahogany with rounded doors, dovetailed drawers, a slatted roll front, internal compartments for envelopes and A4 writing paper, a space to hang shirts and trousers, drawers for underwear and socks, a ventilated drawer for shoes, and even a drinks cabinet from which the owner could serve himself a little restorative, as respectable gentlemen were once inclined to do (fig. 3). In 1951, this “daredevil creation” and the skills of the young man who made it were assessed by the jury of the Craftsmen’s Guild, and approved as outstanding with regard to all the disciplines involved. 13 6 Stueinteriør og møbler tegnet av Sven Ivar Dysthe til Foreningen brukskunsts høstmønstring ”Form og hjem 55”. Living room interior and furniture by Sven Ivar Dysthe at the Association of Applied Art’s autumn exhibition “Form and Home 55”. 18 19 MANNEN BAK STOLEN The Man Behind the Chair Av Thomas Flor Thomas Flor mannen bak stolen the man behind the chair Internasjonal debut International Debut ”Det er kanskje ubeskjedent, men jeg ser ingen grunn til at Norge skal stå tilbake for de andre skandinaviske land på det internasjonale møbelmarked. Vi har tradisjoner og vi har solide håndverkere!” (fig. 21) “It may seem immodest, but I see no reason why Norway should stand in the shadow of the other Scandinavian countries in the international furniture market. We have traditions and capable craftsmen!” (fig. 21) Sven Ivar Dysthe la ikke skjul på ambisjonene sine da han ble intervjuet en septemberdag i 1953.1 Den 22 år gamle bærumsgutten hadde i likhet med den jevngamle danske designeren Poul Kjærholm bakgrunn som møbelsnekker, og ble intervjuet i forbindelse med at han på denne tiden skulle ta fatt på sitt siste år av industridesigner-utdanningen ved Royal College Of Art i London. Professoren hans ved avdelingen Wood, Metals and Plastic var heller ingen ukjent størrelse. Richard Drew Russell hadde i 1944 blitt utnevnt til ”Royal Designer for Industry” og var sentral i utformingen av den framtidsrettete Festival of Britain i 1951. At Russell hadde et spesielt godt øye til Sven Ivar Dysthes arbeider, kommer også fram i avisartikkelen. Her roste han den unge studentens nylig utstilte monter i Victoria & Albert Museum, som noe av det beste laget ved skolen. (fig. 22) Han la også vekt på den unge nordmannens oppfinnsomhet og konstruktive presisjon. Dette var egenskaper som allerede hadde gitt Dysthe en premie for møbeltegninger sammen med medstudenten, australske Robyn C. Wade2 og det ærefulle oppdraget å lage et treskrin som huset gaven fra Royal College of Art til Dronning Elizabeths kroning i 1953. (fig. 23) Sven Ivar Dysthe did not exactly hide his ambitions in an interview he gave one September day in 1953.1 Like the Danish designer Poul Kjærholm, of the same age as Dysthe, the 22-year-old from Norway had trained as a cabinetmaker and the reason for the interview was that Dysthe was about to embark on his final year of training as an industrial designer at the Royal College of Art in London. His professor at the Department of Wood, Metal and Plastics was far from unknown. In 1944 Richard Drew Russell had been appointed “Royal Designer for Industry”, and his influence had been crucial to the design of the forwardlooking Festival of Britain in 1951. The fact that Russell was impressed by Dysthe’s work is also mentioned in the newspaper article. There he praises a display case by his young student, which had recently been shown at the Victoria & Albert Museum, as among the best work ever done at the college (fig. 22). He also alludes to the young Norwegian’s inventiveness and technical precision – qualities that had already earned Dysthe a prize for furniture design, which he shared with his fellow student, the Australian Robyn C. Wade.2 But not least there was the honour of making a wooden casket to hold the Royal College of Art’s gift to Queen Elizabeth on the occasion of her coronation in 1953. (fig. 23) Dansk intermezzo page XXX: 20 Prisma-serien og en bearbeidet versjon av 3001-seriens ”Secretary Chair”, gjengitt fra en filmsekvens i Pål Bang-Hansens dokumentarfilm A Forum for the Arts om Henie Onstad Kunstsenter. 22 Monter, engelsk valnøtt, malt tre, glass og messing for Royal College of Arts gullsmedavdeling. Utstilt i Victoria & Albert Museum, London i 1953. The Prisma range and a revised version of the 3001 “Secretary Chair”, seen here in a screenshot from Pål BangHansen’s documentary A Forum for the Arts about the Henie Onstad Art Centre. Display case in English walnut, painted wood, glass and brass, made for the jewellery department at the Royal College of Art, London. Exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1953. 44 Sven Ivar Dysthe gikk ut av Royal College Of Art i 1954 med skolens høyeste utmerkelse, Diploma of Design, First Class. Den sjeldne utmerkelsen ble ifølge Dagbladet3 bare utdelt i anerkjennelse for usedvanlig dyktighet. I Aftenposten kunne en samtidig lese at den nyutdannete industridesigneren skulle videre til København for å jobbe hos toppfolkene innen den danske møbelkunsten, Danish Intermezzo In 1954, Dysthe graduated from the Royal College of Art with the best achievable grade, Diploma of Design, First Class. According to Dagbladet,3 this rare distinction was only awarded in recognition of exceptional achievements. An article in Aftenposten added that the next stop for the newly qualified industrial designer would be Copenhagen, where 45 mannen bak stolen the man behind the chair et solid og ærlig produkt utført i bøk, teak og flettet sjøgress, som i tråd med tiden hører til under vignetten Scandinavian Design. Siden Hvidt & Mølgaards ansatte oftest jobbet i team, er det usikkert i hvor stor grad Dysthe selv bidro i til dette designet, men fra en av hans tegninger av stolen datert 26. april 1955 ser man hvilket talent han hadde utviklet, både som tegner og i formidlingen av tekniske løsninger. (fig. 24) Tilbake i Oslo fikk Sven Ivar Dysthe i 1955 ”sommerjobb” for møbelhandleren Einar Mortensen A/S. Han fikk i oppdrag å tegne et stueinteriør til den årlige Høstmønstringen i regi av Foreningen Brukskunst.6 Til dette skapte han en relativt rettvinklet polstret sittegruppe med et lavt bord som omkranset tidens konversasjonspunkt, peisen. (fig. 25) Interiøret hadde også en moderne spisestue og skrivebord med tilhørende stoler utført i bøk, teak og flett. Disse var laget egenhendig av Dysthe og tok utgangspunkt i noen av elementene fra modell 316. Men stolene var for- Møbelfabrik as model 316 in 1956 – a robust and honest product made of beech, teak and woven seagrass. It was an supreme example of Scandinavian Design as it was known in that period. Since Hvidt & Mølgaard’s employees usually worked in teams, it is hard to say how much ­Dysthe contributed to this design, but one of his drawings of the chair dated 26 April 1955 certainly gives a clear impression of the skill he had developed, both as a draughtsman and in conveying technical solutions. (fig. 24) In 1955 Dysthe returned to Oslo to take up a “summer job” working for the furniture dealer Einar Mortensen A/S. He was commissioned to design a living-room interior for the annual autumn exhibition organised by the Norwegian Association of Applied Art.6 For this he created an almost rectangular ensemble of upholstered chairs with a low table arranged around what was in those days the typical focus of such conversational spaces, the fireplace. (fig. 25) The interior also had 23 Tegning, lett polstret toseters sofa i japansk alm. Konkurransebidrag i samarbeid med Robin C. Wade, tredjepris i The Furniture Makers Guild Coronation Competition, London 1953. Drawing for a lightly padded settee in Japanese elm. Competition submission in collaboration with Robin C. Wade, third prize in the Furniture Makers Guild Coronation Competition in London, 1953. hvor han også regnet med at han ville lære mye mer om samarbeidet mellom designer og produsent.4 I Danmark skulle Dysthe jobbe på tegnekontoret til de kjente møbeldesignerne Peter Hvidt og Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen, som allerede sto bak mange møbeltyper slik som den banebrytende og eksportvennlige AX-stolen fra 1947. I samarbeid med Hvidt & Mølgaards ansatte arkitekter, fikk Dysthe her et verdifullt innblikk i designprosessene fram til ferdig produkt. Spesielt drillet ble han i detaljene, og hvordan tegnekontorets modeller og prototyper ble saumfart med millimeters presisjon. 5 Et av produktene kontoret jobbet med under Dysthes opphold var utviklingen av spisestuestolen som i 1956 ble presentert som modell 316 av Søborg Møbelfabrikk. Det var 46 he was expecting to work with the best in Danish furniture design and to learn much more about the collaboration between designer and manufacturer.4 In Denmark Dysthe worked in the design office of the well-known furniture designers Peter Hvidt and Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen, who were already famous for a wide range of products, including the pioneering and readily exportable AX chair from 1947. The collaboration with Hvidt & Mølgaard’s staff architects gave Dysthe valuable insights into the design processes that lead to a finished product. In particular, he was drilled in attention to detail and the checking of draughtsmen’s models and prototypes with minute exactitude.5 One of the products the office was developing during Dysthe’s period with the firm was a dining-room chair, presented by the Søborg 24 Tegning, spisestuetol i bøk, teak og flettet sjøgress datert 26.4 1955. Fra tiden hos Peter Hvidt & Orla MølgaardNielsen i København. Sven Ivar Dysthes arkiv. Working drawing for a dining-room chair in beech, teak and woven seagrass, dated 26.4.1955, from Dysthe’s time at Peter Hvidt & Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen in Copenhagen. Sven Ivar Dysthe archives. 47 25 Tegning, polstret stol for Einar Mortensen AS, vist på Foreningen Brukskunst høstutstilling ”Form & Hjem 55”. Designerens første møbel etter oppholdet i Danmark hadde et ­estetisk slektskap med samtidige britiske utøvere som Ernest Race. Sven Ivar Dysthes arkiv. Drawing for an upholstered chair for Einar Mortensen AS, at the Association of Applied Art’s autumn exhibition “Form and Home 55”. Dysthe’s first furniture design after his stay in Denmark had an aesthetic affinity with the work of contemporary British designers such as Ernest Race. Sven Ivar Dysthe archives. enklet både i understell, så vel som i det pragmatiske svungne ryggbrettet som kjennetegner Hvidt & Møldgaards modell. (fig. 26) Lykken smilte til Dysthe, da han i kjølvannet av Brukskunstmønstringen fikk tilbud om jobb som designer for Hiorth & Østlyngen. Skandinavisk stil Denne høsten traff Sven Ivar Dysthe sin kommende ektefelle Trinelise Hauan. Hun var nyutdannet interiørarkitekt under Finn Juhl ved Skolen for Boligindretning i København, og sammen delte de to et felles estetisk ståsted.7 Dysthe begynte raskt å tegne og lage prototyper på verkstedet hos snekkermesterne Hiorth & Østlyngen, på denne tiden et av de toneangivende norske tegnekontorene. Sjefen på kontoret, Arne Hiorth, hadde noen vellykkete møbeltyper bak seg som var i tråd med samtidens utforskning av nye materialer og rasjonell serieproduksjon, blant annet hans 103/80 ”Knock- 48 a modern dining suite and writing table featuring chairs made of beech, teak and wicker. Manufactured single-handedly by Dysthe himself, these chairs included some of the features of the model 316. But the newer item was simpler, both in its lower frame and the removal of the pragmatic curve of the backrest, which was a characteristic of the Hvidt & Møldgaard model. (fig. 26) As a consequence of the Association of Applied Art show, fortune smiled on Dysthe when the firm Hiorth & Østlyngen offered him a job as designer. Scandinavian Style That autumn, Sven Ivar Dysthe also met his future wife, Trinelise Hauan, a recent graduate from the School of Interior Design in Copenhagen, where she had studied under Finn Juhl. The fact that both had spent time in the country meant they shared the same aesthetic outlook.7 It wasn’t long before Dysthe was designing and producing prototypes in the workshop of 26 Skrivebord og stol for Einar Mortensen AS vist på Foreningen Brukskunst høstmønstring 1955. Writing table and dining-room chair for Einar Mortensen AS, at the Association of Applied Art’s autumn exhibition, 1955. 49 27 Utstillingsinteriør fra Foreningen Brukskunsts høstmønstring 1956, hvor Dysthes stoler i kombinasjonen stål og tre ble trukket fram i Bonytt som utstillingens mest interessante. Exhibition interior for Hiorth & Østlyngen at the Association of Applied Art’s autumn exhibition, 1956. Dysthe’s prototype in steel, wood and leather was praised in Bonytt as the exhibition’s most interesting item. 52 53 mannen bak stolen the man behind the chair 32 Tegning, System/Sekvens lenestoler i tre, stål og skinn datert 8.7.1959. Den uvanlige materialkoblingen av tresarger forbundet med stålbein ble det estetiske grepet møbelprodusenten og designeren valgte å satse på. Sven Ivar Dysthes arkiv. Drawing for System/Sekvens armchairs in wood, steel and leather, dated 8.7.1959. The unusual combination of wooden casing and steel legs became the aesthetic feature the manufacturer and designer chose to focus on. Sven Ivar Dysthe archives. 60 61 mannen bak stolen the man behind the chair 33 1001 AF lenestol, palisander, mattbørstet sinkbelagt stål og sort skinn. Designet 1959 og produsert av Dokka Møbler i 1960. Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo. The 1001 AF armchair in rosewood, brushed galvanised steel and black leather. Designed in 1959 and produced by Dokka Møbler in 1960. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo. 62 63 37 1001-serien slik den inngikk sammen med Verner Pantons Barcone og Heartcone stoler i salongbaren til Astoria Hotell Trondheim 1960. The 1001 series as it appeared together with Verner Panton’s Barcone and Heartcone chairs in the lounge bar of the Astoria Hotel in Trondheim, 1960. 72 73 mannen bak stolen the man behind the chair 39 1001 Recliner, regulerbar hvilestol, palisander, forkrommet stål og skinn. Dokka Møbler, 1961. Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo. The 1001 Reclining, adjustable easy chair in rosewood, chrome-plated steel and leather. Dokka Møbler, 1961. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo. 76 77 mannen bak stolen the man behind the chair 45 3001 AX ”Visitor” lenestol, palisander, mattbørstet sinkbelagt stål og skinn. Dokka Møbler, 1961. Kravet om større komfort resulterte i en type stopning som kunne gi assosiasjoner til tidens eksklusive bilseter. Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo. The 3001 AX “Visitor” armchair in rosewood, brushed galvanised steel and leather. Dokka Møbler, 1961. The demand for greater comfort resulted in a kind of padding suggestive of the seats found in the exclusive cars of the day. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo. 84 42 3001 AF konferansestol, palisander, mattbørstet sinkbelagt stål og skinn. Designet 10.3.1961 og produsert av Dokka Møbler 1961. The 3001 AF conference-room chair in rosewood, brushed galvanised steel and leather. Designed 10.3.1961 and produced by Dokka Møbler in 1961. 85 47c XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Interior from the city hall of Münster. 3001 AF and specially made rostrums. Dokka Møbler ca. 1964. 92 93 mannen bak stolen the man behind the chair Dokka-suksessene representerte de derimot ikke, og nettopp dette ble kritisert av Alf Bøe i artikkelen ”Farvel til Sparta”. Han roste inntrykket av eleganse i Dysthes stoler og sofaer, men savnet raffinementet som preget de første Dokkamøblene. Bøe sammenlignet også disse forholdsvis store stykkene kunstindustri med den overstoppete bestefarstolen, og selv om de var vidunderlig behagelige, syntes kunsthistorikeren at de ble for karikerte i sin utstråling av VIP.77 (fig. 56) Frode Braathens bakgrunn fra moteverdenen hadde lært ham at det en ser på kvinnenes kåper det ene året, havner på møbler det neste. Og skinnkvaliteten på de nye Dokka-møblene var like utsøkt og holdbar som det som ble brukt til hansker. Det såkalte anilinskinnet (markedets beste skinnkvalitet) var innfarget gjennom en spesiell fargeprosess som angivelig fikk de duse fargene til å gløde.78 Dokka hadde også innledet et samarbeid med den danske tekstilfabrikanten Fiedler, som produserte et teksturert stoff av den finske tekstildesigneren Marjetta Metsovaara. Dette møbelstoffet, som ble vist på noen av nyhetene på denne vandreutstillingen, skilte mellom blank og matt overflate i gjengivelsen av et sirkelmønster. Her var Braathen på høyde med hva som skjedde hos motehuset Marimekko, men disse mønstrete tekstilene passet til helt andre møbeltyper enn Dokkas i utgangspunktet maskuline framtoninger. Et poeng som også ble trukket fram i det danske tidsskriftet Mobilias særutgivelse i november 1965, som i sin helhet var dedikert Dokka i forbindelse med denne vandreutstillingen.79 Oslo-visningen ble noe forkortet fordi Braathen hadde fått vite at den norske kronprinsen skulle være i New York i forbindelse med et idrettsarrangement. I all hast fikk han fløyet over hele arrangementet som skulle monteres i varehuset Spivack International, og Kronprins Harald åpnet utstillingen. (fig. 57) I New York ble Sven Ivar Dysthes nyhet 7001 innkjøpt til den norske ambassaden i Washington, og fra denne utstillingen kunne en lese en større begeistring for møblene enn i Norge: At hele Dokka-kolleksjonen utmerket seg i forhold til den typiske skandinaviske stilen, nesten som haute couture.80 104 one year end up on furniture the next. And the quality of the leather used in the new Dokka creations was as exclusive and durable as that used for gloves. So-called aniline leather (the best the market could offer) was dyed using a special process that supposedly made the mellow colours glow.78 Dokka had also initiated a collaboration with the Danish textile manufacturer Fiedler, who produced a textured fabric by the Finnish designer Marjetta Metsovaara. This furniture fabric, which appeared on some of the new models in the touring exhibition, exploited the contrast between glossy and matt expanses in a repetitious circular pattern. In this Braathen demonstrated that he understood the spirit of what was emerging from fashion houses like Marimekko, yet these patterned fabrics were better suited to a kind of furniture that had little in common with the fundamentally masculine mood of the Dokka range – a point that was also made in a special edition of the Danish magazine Mobilia, published in November 1965, which was devoted in its entirety to Dokka on the occasion of its new touring exhibition.79 When this same exhibition came to Oslo, it was cut short because Braathen had learnt that the Norwegian crown prince was travelling to New York in connection with a sporting event. In great haste he had the entire display flown across the Atlantic and installed in the Spivack International department store, where it was duly opened by Crown Prince Harald. (fig. 57) The exhibition in New York, where Dysthe’s new 7001 was purchased for the Norwegian Embassy in Washington, demonstrated that there was greater enthusiasm for Dokka’s furniture there than in Norway – and that the Dokka range stood out as distinct from the typical Scandinavian style, almost like haute couture.80 Laminette While Dokka’s touring exhibition was on the road, Dysthe was working on the drawings for what would become another success story in Norwegian industrial design – a chair that most Norwegians have sat on at some time or other, the Laminette. Dysthe had been working on an idea for a 56 7001 H lenestol med fotskammel, skinn og palisander. Designet 18.5.1964 og produsert av Dokka Møbler fra 1965. Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo. The 7001 H armchair with footstool in leather and rosewood. Designed 18.5.1964 and produced by Dokka Møbler in 1965. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo. 105 Plast og popdesign Plastic and Pop-Design Widar Halén Widar Halén plast og popdesign plastic and pop-design Høsten 1952 ble Sven Ivar Dysthe student på det prestisjetunge Royal College of Art linje Wood, Metal and Plastics, og han lærte der å kjenne de nye plastmaterialene. Et studentarbeid fra 1953 var blant annet et plastfutteral for en Remington barbermaskin.1 I løpet av en 20-årsperiode gjorde den kjemiske industrien plastmaterialene mer attraktive ved stadige utviklinger av nye typer og forbedringer. Etter flere hundre års produksjon av de såkalte kassemøblene, foregikk det nå en fullstendig stilendring mot friere og rundere former, som vesentlig skyldtes introduksjonen av plast i møbelindustrien. Dysthe fulgte godt med i denne utviklingen og i 1958 deltok han i Askim Gummivarefabrikks konkurranse for møbler i firmaets produkt Viking skumgummi. Han vant førstepremie og innkasserte 2000 kroner for den beste stolen og 2500 kroner for den beste sovesofaen. Juryens formann, arkitekt Odd Brochmann, presiserte at ”Sven Ivar Dysthes stol og sovesofa står i særklasse både når det gjelder formen og når det gjelder hensynet til anvendelse av skumgummi”.2 Det var det siste som var hensikten, for Askim Gummivarefabrikk hadde siden ca 1950 produsert skumgummi til møbelstopping etc., men etter at skumplasten kom i 1953 hadde de fått en stor konkurrent. Fabrikken hadde ikke selv noen møbelproduksjon, men de ville lage modeller av vinnerutkastene, som møbelprodusentene så kunne kjøpe rettighetene til. Høsten 1958 ble sofaen og stolen til Dysthe vist på Foreningen Brukskunsts 40-årsjubileumsutstilling i Kunstnernes Hus.3 (fig. 90 ) Her viste de også Trinnelises og Sven Ivars felles forslag til arbeidsrom. Sove- page XXX: 89 Popcorn i glassfiberarmert polyester med forkrommet stålunderstell. To med skaibetrekk, Møre Lenestolfabrikk 1968 og to prototyper for nyere versjon fra 1995, produsert av Fora Form 2012. Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo. Popcorn chairs in fibreglass-reinforced polyester with chrome-plated chassis. Two chairs with Skai leather upholstery, Møre Lenestolfabrikk from 1968, and two prototypes from 1995 for the later version were produced by Fora Form in 2012. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo. 158 In autumn 1952, Sven Ivar Dysthe began studying at London’s prestigious Royal College of Art in the Department for Wood, Metal and Plastics, where he became acquainted with new plastic materials. One of his student works from 1953 was a plastic case for a Remington shaver.1 Over a twenty-year period the chemical industry had made plastics more attractive, thanks to constant improvements and the development of new types. Furniture design, which for centuries had been stuck with jointed box structures, suddenly underwent a complete change of style toward freer and rounder shapes, a change that was attributable in large part to the industry’s adoption of plastics. Dysthe paid close attention to these developments, and in 1958 he participated in a competition organised by Askim Gummivarefabrikk for furniture that would use the company’s Viking foam rubber. Winning first prize, he received 2,000 kroner for the best chair and 2,500 kroner for the best sofa-bed. The chairman of the jury, architect Odd Brochmann, stressed that “Sven Ivar Dysthe’s chair and sofa-bed are in a class of their own, in terms of both design and the use of foam rubber.”2 It was the latter that mattered for Askim Gummivarefabrikk, which had been producing foam rubber for upholstery and other uses since around 1950, but the advent of foam plastics in 1953 had confronted the firm with a major competitor. Although the factory did not produce furniture itself, it commissioned prototypes of the winning designs, the rights to which it hoped furniture manufacturers would then buy. In autumn 1958, Dysthe’s chair and sofa-bed were shown at the Norwegian Association of Applied Art’s fortieth anniversary exhibition at Kunstnernes Hus. 3 (fig. 90) Also on show at this event was a workroom interior jointly designed by Trinelise and Sven Ivar Dysthe. The latter’s sofa-bed was a simple rectangular item, while the chair had a more organic form reminiscent of the famous Womb Chair that Eero Saarinen had designed for Knoll in 1946. Dysthe’s chair had a broad rounded backrest and an ergonomic bulge to support the lower back. In later years Dysthe admitted that his winning proposal reflected his fascination with American design, and that he had indeed been inspired by Saarinen’s famous chair.4 This he might have sofaen var enkel og rettvinklet, mens stolen hadde en mer organisk form som kan minne om Eero Sarinens berømte Womb-stol for Knoll fra 1946. Den hadde en bred avrundet rygg med en ergonomisk forhøyning mot sitteputen. Dysthe har i ettertid bekreftet at vinnerutkastene avspeilet hans fascinasjon for amerikansk formgivning, og at han hadde vært inspirert av Saarinens berømte stol.4 Kanskje så han denne på den meget omtalte utstillingen ”Amerikansk Form”, som turnerte i de nordiske landene, og som ble vist i København i 1954, da han bodde der. Skumgummien var imidlertid noe kostbar og det skulle vise seg at skumplasten som Lauritz Sundes Porolon A/S hadde sikret seg rettighetene til i 1953, var atskillig rimeligere og mer holdbar, og derfor etter hvert ble foretrukket i møbelindustrien.5 Etterkrigstiden var en periode med omstilling og stor utvikling for møbelindustrien i Norge, og 1950-tallet er preget av effektivisering og rasjonalisering. Norske møbelprodusenter reiste på studieturer til USA og det daværende Vest-Tyskland, som var foregangsland. Nye materialer som skumgummi og skumplast effektiviserte nå stoppemetodene, og i 1955–56 ble de første hele møblene av fiberarmert styropor og polyester produsert i Norge.6 Inspirasjonen kom delvis fra USA og de revolusjonerende plastmøblene designet av Charles Eames og Eero Saarinen, men også fra VestTyskland hvor man i krigsindustrien hadde eksperimentert med bruken av styropor, polyuretan og andre plastmaterialer. Lauritz Sunde i Ålesund hadde kommet i kontakt med skumplast laget av polyuretan under en reise i Vest-Tyskland i 1952, og allerede året etter hadde han sikret seg rettighetene til dette materialet i Norge og produsert landets første stol i skumplast, Ja-va, som sies å være den første helstøpte skumplaststolen i verden.7 En annen gründer, direktør Gerner Svendsen i Grenax Plastics Co. i Kristiansand, var i 1951 i Vest-Tyskland og kom hjem med plastmaterialet styropor, som han ga til sin assistent Rudolf Torjussen. Han begynte å eksperimentere med dette materialet med tanke på møbelproduksjon i samarbeid med Johan Jansen, som laget støpeformer i aluminium og Henry W. Klein seen at the widely discussed exhibition “American Form”, which visited Copenhagen in 1954, when Dysthe was living there, as part of a tour of the Nordic countries. Foam rubber was, however, a costly material, and it would soon become evident that foam plastic, which Lauritz Sunde’s Porolon AS had been producing under licence since 1953, was both cheaper and more durable, and hence preferable for the furniture industry.5 The post-war period was one of rapid change and development for the furniture industry in Norway, which moved relentlessly towards greater efficiency and rationalisation during the 1950s. Norwegian furniture manufacturers undertook study trips to the U.S. and what was then West Germany, both of which were frontrunners in the field. New materials such as foam rubber and foam plastic permitted more efficient upholstery techniques, and in 1955–56 the first items of furniture to consist entirely of fibre-reinforced polystyrene and polyester were produced in Norway.6 The inspiration came in part from the U.S. and the revolutionary plastic furniture designed by Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen, but also from West Germany, where factories working for the war industry had experimented with the use of polystyrene, polyurethane and other plastics. Lauritz Sunde from Ålesund first encountered polyurethane foam on a trip to West Germany in 1952. A year later, he had secured a licence to produce this material in Norway, whereupon he produced the country’s first plastic chair, the Ja-va, reputed to be the first single-cast foam plastic chair in the world.7 Another national pioneer was Gerner ­Svendsen, managing director of Grenax Plastics Co. in Kristiansand. Svendsen returned from a trip to West Germany in 1951 with samples of polystyrene, which he handed over to his assistant Rudolf Torjussen. Torjussen began experimenting with the material with a view to producing furniture in collaboration with Johan Jansen, who constructed the aluminium moulds, and the designer Henry W. Klein. A former student of Finn Juhl in Denmark, Klein experimented with a variety of seat shells. In 1955, this innovative partnership produced Norway’s first fibre-reinforced plastic chair, Model 1001. The following year, Rudolf Torjussen applied for a patent for their casting tech- 159 plast og popdesign plastic and pop-design 92 Arbeidstegning til stolen Planet datert 6.10.1963. Sven Ivar Dysthes arkiv. 93 Planet i ny versjon med sving og vippefunksjon. Fora Form, 2002. Working drawing for the Planet chair, dated 6.10.1963. Sven Ivar Dysthe archives. The new version of Planet with swivel and tilt function. Fora Form, 2002. 162 163 plast og popdesign plastic and pop-design som var designer. Klein var utdannet under Finn Juhl i Danmark og han eksperimenterte med en rekke stolskall. I 1955 kunne oppfinnergruppen produsere den første fiberarmerte plaststolen i Norge, Modell 1001. Støpemetoden ble registret hos Patentstyret av Rudolf Torjussen i 1956 (gitt patentrettighet i 1958), og stolen ble først produsert av Sør-Camping Co, det senere Modellmøbler AS og Plastmøbler AS. Patentet med rettigheter til å produsere noen av Kleins første møbelmodeller ble solgt til ikke mindre enn 46 land og kom til å revolusjonere møbelindustrien verden over.8 I 1956 produserte Herbert Waarum, som hadde etablert firmaet Herwaplast i Grimstad, den første stolen i glassfiberarmert polyester i Norge, en teknikk han hadde lært under et opphold i USA i 1948, men denne ble aldri masseprodusert.9 Planet Det var disse norske eksperimentene med plaststøpeteknikker samt Lauritz Sundes såkalte ”sundolitt” (polyuretan), som lå til grunn for Sven Ivar Dysthes første skallstol. Den kuleformete Globus, som han tegnet høsten 1963 for Møre Lenestolfabrikk ble produsert under navnet Planet i 1964. (fig. 91) I Bonytt 1966 ble stolen anmeldt i en artikkel kalt ”Fra kube til kule”, og forfatteren spurte om Dysthe nå ville endre stil fra ”elegant kubisme” til mer runde former. Til dette svarte Dysthe: ”Det gikk nå mer tilfeldig for seg. En tekstilfabrikk ønsket seg en ball av noe slag for å prøve et nytt elastisk stoff. Og jeg tenkte, skal det være rundt så la det være virkelig rundet – en kule. Størrelsen oppsto ikke ved tegnebrettet. På fabrikken tok vi og pumpet opp en garnblåse av plast til jeg syntes det virket passe og sa stopp. Etterpå ble det jo flere modeller, men sånn begynte det”.10 Garnblåsen de brukte var blant de første i plast produsert av Polyform AS i ”sundolitt” polyuretan, levert fra Sunde’s Porolon AS. Begge disse bedriftene lå i Ålesund. Garnblåsen ble påført en delelinje som med et sirkelformet snitt delte formen i to halvkuler. Ut mot snittet ble den belagt med glassfiberarmert polyester, og da 164 nique (issued in 1958), after which the chair went into production at Sør-Camping Co. (later Modellmøbler AS) and Plastmøbler AS. The right to use this patented technique in the production of some of Klein’s early furniture designs was eventually sold to no less than forty-six countries, thus helping to revolutionise the furniture industry worldwide.8 In 1956, Herwaplast, a firm in Grimstad founded by Herbert Waarum, produced Norway’s first chair made of fibreglass reinforced polyester, a technique Waarum had learnt during a trip to the U.S. in 1948, but this was never mass-produced.9 Planet It was these Norwegian experiments with plastic moulding techniques and Lauritz Sunde’s socalled “Sundolitt” (polyurethane) that provided the background for Sven Ivar Dysthe’s first shell chair, the hemispherical Globus. Designed in the autumn of 1963 for Møre Lenestolfabrikk, it was produced under the name Planet in 1964. (fig. 91) A review of the chair entitled “From the cube to the ball” in a 1966 edition of Bonytt asked whether Dysthe was changing his style from “elegant cubism” to more rounded shapes. To this Dysthe responded: “It came about more by accident. A textile factory wanted something rounded to test out a new stretch fabric. And I thought, if it’s going to be round then let’s make it really round – spherical. The size was not decided at the drawing board. At the factory we pumped up a plastic marking buoy until I thought it looked big enough and said stop. Later we made a number of different models, but that’s how it started.”10 The marking buoy they used was one of the first ever made in plastic. It was produced by Polyform AS using “Sundolitt” polyurethane, supplied by Sunde’s Porolon AS, both based in Ålesund. Having drawn a line around the marking buoy, it was cut into two hemispheres. A negative form was then produced by covering one half of the buoy with fibreglass-reinforced polyester. Once this had hardened, the buoy was removed, leaving the mould in which the shell of the chair would be produced. This process was handled by Plastkon- 91 Planet svingstol i glassfiberarmert polyester, skinn, forkrommet stål og palisander med tilhørende bord, tegnet1963. Møre Lenestolfabrikk, 1964. Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo. Planet swivel chair and table in fibreglass-reinforced polyester, leather, chrome-plated steel and rosewood, designed in 1963. Møre Lenestolfabrikk, 1964. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo. 165 plast og popdesign plastic and pop-design Skibindinger i plast Plastic Ski Bindings På 1960-tallet eksperimenterte Dysthe også med andre oppfinnelser enn runde plaststoler, og han har senere sagt at den nye ”skibindingen i plast var den største utfordringen”.26 Å bryte Rottefella- bindingens herredømme var ingen lett sak, men det var dette han ønsket å gjøre da han i 1965 ble kontaktet av skismøringsprodusenten Astra-Wallco AS. Dysthes nabo på Nadderud, Jon Sølvberg arbeidet på denne fabrikken, og var blitt oppmuntret av den berømte trener for landslaget, Kristen Kvello, til å lage en ny skibinding. Dysthe måtte finne en annen løsning enn Rottefellas, og eksperimenterte med en såkalt topunktsbinding med to klør som gikk inn i to festepunkter i skistøvelen og som ble patentanmeldt 13.mars 1965. (fig. 99) Han holdt på i tre år for å finne den beste løsningen, og fikk endelig patentrettighter den 19. desember 1968.27 Noen prøvebindinger ble produsert i små kvanta hos Astra-Wallco AS. Firmaet oppga imidlertid prosjektet og det ble overtatt av Bergans.28 Dette firmaet hadde laget glassfiberski siden 1962 og forsto at Dysthes oppfinnelse ville medføre en total revolusjon innen skiløping. Den 20. mars 1969 leverte Dysthe den endelige tegningen, og Bergans lanserte til skisesongen samme år verdens første vellykkete topunktsbinding.29 (fig. 100) Den var imidlertid laget i aluminium med klør og bøyle produsert av Oslo Spiral og Trådvarefabrikk, men med ”hælplate” i plast og ”plast selvklebende monteringsplate med huller som letter monteringen”. Bergans reklamerte stolt for sin ”Revolusjonerende nye 2-punkts tåbinding”: ”Bergans patenterte topunkts tåbinding er konstruert etter nye prinsipper med maksimal ledighet og sikkerhet som mål. Bindingen opereres med skistaven og høyre og venstre binding går om hverandre”.30 Det var særlig den enkle betjeningen med staven og at høyre og venstre binding var like som var revolusjonerende og noe helt nytt, men andre fordeler var ifølge reklamen: ”maksimal ledighet, enkel montering, effektiv hælstyring og eliminering av kladding på hælene”.31 Den nye oppfinnelsen var imidlertid avhengig av nye skistøvler med to festepunkter foran In the 1960s, Dysthe experimented with other inventions besides round plastic chairs, later remarking that his new “plastic ski bindings were his biggest challenge.”25 It was no easy matter to break the market dominance of the traditional Rottefella binding, yet this was the task Dysthe set himself when the ski wax manufacturer AstraWallco AS approached him in 1964. Jon Sølvberg, a neighbour of Dysthe’s at Nadderud, worked for the firm and had been encouraged by the renowned coach of Norway’s ski team, Kristen Kvello, to develop a new binding. Recognising the need for a mechanism that differed from the Rottefella, Dysthe experimented with a so-called twopoint binding, which consisted of two clamps that latched onto two fastening points on the ski boot. A patent application was submitted for this design on 13 January 1965. (fig. 99) After persevering with his search for the best solution for three years the patent was finally approved on 19 December 1968.26 Astra-Wallco AS produced small sample quantities of the binding,27 but the company decided to abandon the project, which was then taken over by Bergans.28 As a producer of fibreglass skis since 1962, Bergans recognised that Dysthe’s invention had the potential to revolutionise skiing. On 20 March 1969 Dysthe delivered his finished drawings, and in time for the ski season that same year Bergans launched the world’s first successful two-point binding.29 (fig. 100) The aluminium clamps and clips were produced by Oslo Spiral og Trådvarefabrikk, while the “heel plate” was made from plastic with a “plastic adhesive mounting plate with holes for easy assembly.” Bergans advertising was obviously proud of its “Revolutionary new two-point toe binding”; “Bergans’ patented two-point toe binding is designed using the latest principles with the goals of maximum comfort and safety. The bindings … are operated using the ski stick, and the right and left bindings are interchangeable.”30 What was revolutionary and entirely new was the ease of operation using the ski stick and the fact that the right and left bindings were identical, but additional benefits stressed in the advertising included “maximum comfort, easy assembly, ef- 176 177 plast og popdesign plastic and pop-design 102 En serie skibindinger som først viser tre prototyper av aluminiumsbindinger 1966–69, deretter plastbindingene Symmetric i Arnite plast, Bergans 1973, Racer i Arnite plast, Bergans 1976 og Micro i hardplast, Bergans 1980. A series of ski bindings showing three prototypes for the first aluminium binding 1966–69, followed by the plastic bindings Symmetric in Arnite plastic in 1973, Racer in Arnite plastic in 1976 and finally Micro in hard plastic in 1980. All produced by Bergans. 184 185