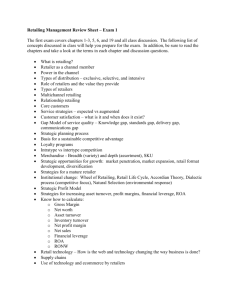

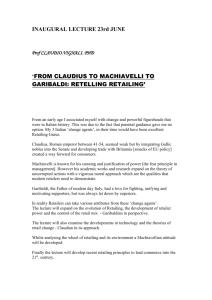

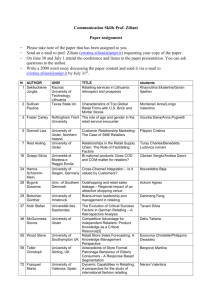

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322878809 The Evolution and Future of Retailing and Retailing Education Article in Journal of Marketing Education · February 2018 DOI: 10.1177/0273475318755838 CITATIONS READS 164 13,398 3 authors, including: Dhruv Grewal Scott Motyka Babson College Babson College 275 PUBLICATIONS 55,657 CITATIONS 9 PUBLICATIONS 494 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Dhruv Grewal on 22 July 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE 755838 research-article2018 JMDXXX10.1177/0273475318755838Journal of Marketing EducationGrewal et al. Article The Evolution and Future of Retailing and Retailing Education Journal of Marketing Education 2018, Vol. 40(1) 85­–93 © The Author(s) 2018 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475318755838 DOI: 10.1177/0273475318755838 journals.sagepub.com/home/jmed Dhruv Grewal1, Scott Motyka2, and Michael Levy1 Abstract The pace of retail evolution has increased dramatically, with the spread of the Internet and as consumers have become more empowered by mobile phones and smart devices. This article outlines significant retail innovations that reveal how retailers and retailing have evolved in the past several decades. In the same spirit, the authors discuss how the topics covered in retail education have shifted. This article further details the roles of current technologies, including social media and retailing analytics, and emerging areas, such as the Internet of things, machine learning, artificial intelligence, blockchain technology, and robotics, all of which are likely to change the retail landscape in the future. Educators thus should incorporate these technologies into their classroom discussions through various means, from experiential exercises to interactive discussions to the reviews of recent articles. Keywords learning approaches and issues, marketing education issues, experiential learning techniques, retailing, e-commerce/Internet marketing, course content, teamwork/projects/issues Retailing and retailers face a rapidly changing market landscape, due largely to the ways modern customers shop: instore, online, through mobile channels, and even with emerging machine-to-machine commerce (Grewal, Roggeveen, & Nordfält, 2017; Rafaeli et al., 2017; Roggeveen, Grewal, Townsend, & Krishnan, 2015; Roggeveen, Nordfält, & Grewal, 2016). Such shifting consumption patterns are partly a function of technological advances associated with novel offerings and capabilities provided by the Internet of things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain technologies, and robotics (Rafaeli et al., 2017). These impending technological promises follow from the relatively recent emergence of now familiar advances in the Internet, computing and storage capabilities, big data, and retail analytics. These trends have prompted the enormous growth of Internet-based retailing, as well as tremendous challenges and opportunities for the retail sector. Amazon has led the way, establishing a powerful competitive advantage over most retailers. Big data and retail analytics are less obvious in everyday consumers’ lives, but their influence has been equally important (Bradlow, Gangwar, Kopalle, & Voleti, 2017). Retailers are developing their analytical capabilities to understand and serve customers better, price products and services dynamically, and manage the flow of merchandise in the supply chain. As retailing and retailers change, it is equally important for retailing education to evolve in parallel. Retailing education must reflect technological advances, in all its various forms. First, the content covered needs to be up-to-date. Second, digital, online pedagogical solutions should integrate mobile and smart devices in the classroom. Third, retailing education continues to need relevant case studies and vignettes on novel and emerging issues (e.g., Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods), along with relevant experiential exercises. Accordingly, we structure this article to acknowledge the past, the present, and the future of retailing and retailing education. First, we examine major changes in a key retailing textbook (Retailing Management; Levy, Weitz, & Grewal, 2014, 2018) and the supporting material it has provided, from its first through 10th editions, to highlight how retail education has and continues to evolve.1 In this analysis, we first cover significant retailing innovations that have changed the retail and consumer landscapes and tie them to changes in retail education. Second, we discuss current challenges and shifts in retailing that are influencing retail education. Third, we pursue insights into several new technologies that have the promise of changing retailing and its teaching, such as the IoT, machine learning, AI, and blockchain technologies. 1 Babson College, Babson Park, MA, USA Keck Graduate Institute, Claremont, CA, USA 2 Corresponding Author: Dhruv Grewal, Toyota Chair of Commerce and Electronic Business, Professor of Marketing, Marketing Division, Babson College, 213 Malloy Hall, Babson Park, MA 02457, USA. Email: dgrewal@babson.edu 86 Journal of Marketing Education 40(1) Figure 1. Retailing technology timeline. Note. Adapted from Braun (2015). Figure 2. Technology topics covered in Retailing Management (1992-2018 [10 editions]). Retailing in Textbooks: The Past To assess the potential of technology to change both retailing and retailing education, we take a historical perspective and map key technological advances in retailing, as indicated by each edition of Retailing Management, a popular retailing textbook, according to when the innovations were introduced (Levy et al., 2014; see Figures 1 and 2). Although core retailing concepts (e.g., visual merchandising, pricing, atmospherics) have largely remained the same, the ways retailers deliver on these principles have changed tremendously, particularly due to technological innovations. The widespread introduction of the Internet in 1994 eventually led to the notion of omnichannel retailing, defined as a consistent, integrated shopping experience across all channels maintained by the retailer. In the face of these rapid developments, not just retailers but also educators have had to constantly refine their understanding. The second edition of Retailing Management (Levy & Weitz, 1995) was published a year after the popular introduction of the Internet. It reflected the then-timely technology changes, such as quick-response delivery systems and their uses of electronic data interchange, enabled by the Internet, to reduce inventory costs. Amazon also launched in 1995, initiating the start of the e-tailing revolution. In the third and fourth editions of Retailing Management, the authors describe the Internet channel as “non-store and electronic retailing,” but as the importance of this channel grew, so did the terminology. As the Internet took wider hold, retailers began to understand the value of online retailing, leading 87 Grewal et al. them to prioritize this channel equally with brick-and-mortar stores. As a result, educators shifted from describing an “electronic channel” and instead began referring to “multichannel retailing,” such that the fifth to ninth editions of Retailing Management (2003-2014) acknowledge their equal importance. Then in 2007, the Apple introduced the iPhone, and by 2009, the smartphone, which included competing Android models, was widely adopted. Consumers no longer had to choose whether to shop in either a brick-and-mortar store or at their desks on a computer in their homes or offices. Smartphones with mobile applications empowered consumers to shop not only anytime but also anywhere. This expansion represented a great opportunity for retailers, but it also meant new challenges. Consumers demand consistency from the retail experience. If a customer can compare in-store prices with online prices in real time on a smartphone, retailers cannot manage their Internet and brickand-mortar channels independently. Thus, the concept of “omnichannel retailing,” which appeared in Retailing Management’s 10th edition is thus more than just offering customers products through multiple channels. It is the coordination of offerings across retail channels that provides a seamless and synchronized customer experience, using all of the retailer’s shopping channels (Witcher, Swerdlow, Gold, & Glazer, 2015). Recognizing that online retailing was changing how consumers bought, competitors have responded actively, as recently exemplified by Walmart’s massive investment to acquire Jet.com ($3.3 billion in cash and stock), to enhance its competitive ability relative to Amazon and the rest of the marketplace (Stone & Boyle 2017). At almost the same time, Amazon acquired Whole Foods for $13.4 billion to enhance its brick-and-mortar capacities (Wingfield & de la Merced, 2017) Brick-and-mortar retailers and online channels also increasingly feature a cooperative effort, such that Amazon obtained Whole Foods for $13.4 billion to enhance its brickand-mortar capacities (Wingfield & de la Merced, 2017). Overall, conventional brick-and-mortar retailers need to coordinate their activities across multiple channels, in formats that reflect multi- or omnichannel integration, to leverage the power of their traditional channels, exploit the benefits of advanced technology channels, and achieve seamless integration across all their customer touchpoints (Ailawadi & Farris 2017; Grewal, Bart, Spann, & Zubcsek, 2016; Inman & Nikolova 2017). Retailing in and Beyond the Classroom: The Present To establish the current state of the art, this section first outlines real-world retail developments, then describes how those developments and advanced pedagogy should be integrated into retailing curricula. Retailing Analytics’ Growing Importance When retailers gain greater insights into their customers by combining data sets, such as details about purchase data, location data, and social media data, they can leverage this information to create value for consumers. Retailers such as Kroger, CVS, and Target are investing heavily in retail analytic capabilities and moving from traditional loyalty programs to systems that integrate and make effective use of varied data to engage customers (Grewal, 2018). They are also spending more of their promotional budgets on online and social media-based promotions, such as advertising through Google AdWords, Instagram, and Facebook. At the same time, customers are making increased use of digital channels, by posting reviews about products, services, and providers, which can help other consumers make informed purchase decisions. After purchasing, customers also post information to their social network feeds about the purchases they have made, as well as their opinions and reviews of the product and overall shopping experience. Kumar, Anand, and Song (2017) have linked profitability to the increased use of analytics, such that retailing analytics promise to take an ever-growing role, in both retailing and retailing education. The strategic use of analytics can drive insights at four levels: market, firm, store, and customer (Kumar et al., 2017). For example, retailers might analyze store-level data to create geo-fenced mobile ads (delivered to mobile users in predefined geographic areas) or to understand the effects of specific store atmospherics on sales, customer satisfaction, or basket size. To facilitate such analyses, retailing students will need to learn Python (used for machine learning and natural language processing [NLP]; www. python.org) and SQL (used to access data from databases) programming languages. To facilitate managerial decision making, the results of these analytics also must appear in easy-to-understand, dynamic dashboards using visualization programs such as Tableau. As these topics continue to grow in importance and complexity, we expect the development of new elective courses, related to retailing management but focused primarily on retail analytics, dashboards, and data visualization through tools such as Tableau. Educators can access free software licenses for students, sample data sets, and classroom activities through its Tableau for Teaching program (https://www.tableau.com/academic/teaching). The primary method retailers use to analyze social media data is sentiment analysis, often monitored through various social media listening dashboards, as offered by companies such as Salesforce Radian6 and Brandwatch. Social media analysts search for key terms related to their brand and use NLP to score each post as positive or negative (Pang & Lee, 2008), then aggregate the scores across consumers to gain a measure of their overall attitude toward the brand (Roggeveen & Grewal, 2016). For example, Yelp provides an excellent opportunity for restaurants to understand their customers and 88 develop innovative, appealing offerings. Regional managers can analyze sentiments about their restaurants to identify customers’ concerns about prices, atmospherics, service quality, product offerings, and other aspects of the retail offering. Sentiment analysis is rapidly evolving, with the focus shifting from categorizing posts as positive or negative to identifying the strength of both positive and negative sentiments (Ordenes, Ludwig, de Ruyter, Grewal, & Wetzels, 2017). People rarely express a completely positive or negative view; instead, consumer reviews tend to highlight both positive and negative aspects (e.g., “I love how inexpensive the store is, but hate that it’s so disorganized” (Ordenes et al., 2017). Current sentiment analysis methods classify mixed sentiment posts as “neutral,” but doing so ignores rich information about their customers’ complex sentiments. By assessing the strength of positive and negative sentiment separately, retailers can gain a better understanding of their customers and incorporate these insights into their predictive models and strategy. Big Data As the cost of data storage and processing continues to decline, retailers are collecting more data, including purchase data from enterprise systems (e.g., quantity purchased, price and cost of each item, size of discounts applied, composition of shopping basket, and time and date of purchase; Grewal et al., 2017) as well as social media and demographic information about customers. Big data provide a wealth of both opportunities and challenges. In particular, they allow retailers to create massive data warehouses that combine multiple data sets and thus uncover unique insights. For example, retailers can combine customer loyalty data, demographic information (e.g., age, gender), and geographic data (e.g., store locations, weather forecasts) to build better demand models that enable them to better manage inventory and labor costs. Big data originally were defined by the “three Vs”: volume (amount of data), variety (types of data), and velocity (rate at which data are generated; McAfee, Brynjolfsson, & Davenport, 2012). In recent years, researchers and practitioners have called for adding a fourth V: veracity (Mattmann, 2013). Retailers accustomed to working with market research firms that provide well-validated measures and weighted samples will need to learn to cast a more skeptical eye on big data analytics. When data are gathered from multiple sources with varying degrees of validity, examining the accuracy or veracity of those data, before making managerial decisions, is critical. Furthermore, big data create significant security risks. The 2017 breach of Equifax, in which the personal information of 145 million U.S. consumers was stolen, the 2016 hack of Uber in which 57 million riders’ and drivers’ data were stolen, and the 2017 hack of Forever 21’s point-of-sale system are all Journal of Marketing Education 40(1) prime examples. As the amount of data stored by retailers grows exponentially, so do the demands for retailers to adopt a common set of procedures to protect the security of their customer data and to ensure ethical uses of the related analytics. Any solutions retailers implement also need to pursue win–win outcomes, for the firm and the customer. For example, website ads are often customized on the basis of data, which customers did not know were being collected. They do not like shopping for an air mattress on Amazon, then seeing ads for air mattresses on every website they browse for weeks afterward. Research has shown though that retailers can reduce or eliminate consumer aversion to personalized ads, simply by disclosing that their ads are personalized (Aguirre, Mahr, Grewal, Ruyter, & Wetzels, 2015). Active Learning and Digital Pedagogy As smartphones, tablets, and laptops have been more widely adopted, retailing education also has begun to shift, away from traditional pedagogical models that use static business cases and toward a more dynamic, active learning model. Unlike traditional, lecture-based classes, active learning requires students to engage and become partners in their learning experience. Research has found active learning can increase grades on examinations and concept inventories and significantly increase the odds of passing the class (Freeman et al., 2014). For example, case studies and vignettes pertaining to innovative topics and relevant experiential exercises (e.g., retailer analyses, simulations) encourage students to apply the knowledge they have gleaned from their textbooks and class discussions to real-world problems. Through active learning, students gain a better understanding and appreciation of core concepts and are more motivated to engage with the learning process. The following sections describe some example exercises that educators can incorporate into their classes to encourage active learning. Using Simulations. Textbooks are a cornerstone of retailing education, but students often struggle to connect the various topics in a holistic fashion. Educators tend to cover a different retailing topic each week, and though it is clear to the educator how the concepts relate, inexperienced students learn these topics in a disconnected fashion. To make the content “come alive,” students might engage in retailing simulations that force them to combine multiple concepts covered in the course to manage a virtual business, perhaps in a dynamic, competitive environment. By applying the concepts actively, students learn the content better; research shows that overall class grades improve with simulation performance over the course of a semester (Woodham, 2017). Educators can choose from simulations that focus on managing a retail location, such as Interactive Simulation’s Entrepreneur (https://www.interpretive.com/business-simulations/entrepreneur/), or managing a manufacturer and its retail channels, 89 Grewal et al. such as McGraw Hill’s Practice Marketing (http://www. mhpractice.com/products/Practice_Marketing). There are two general options for integrating simulations into a course: benchmark and direct competition. In benchmark simulations, each group competes against a computer in an independent but identical business environment. This option supports easy assessments across groups. However, such simulations are less dynamic and engaging, because teams are playing against a computer. Because the simulation is standardized, students can readily discuss strategies across groups or search for optimal solutions online, which may diminish the value and power of this learning experience. In a direct competition simulation, the student groups instead compete against one another. Students thus are more engaged, because they know their competitor is a real person. The business environment also is dynamic, changing according to each group’s decisions, so students are less likely to discuss strategies with other groups (i.e., their competitors) and cannot find solutions online, because each simulation game is unique. The use of simulations can greatly enhance learning experiences (Woodham, 2017), but simulations also require careful integration into the class. An instructor should establish 8 to 10 groups of three to four students each (depending on class size). Then two separate simulation games can be run, with four or five teams assigned to each. It is possible to run 10 separate groups within a single simulation, but teams that underperform at first often face too much competition, such that they struggle throughout the simulation and begin to disengage from the learning process. A business environment of four to five groups makes it possible for underperforming teams to improve, which keeps them engaged in active learning. We also recommend that rather than using simulation decisions as homework assignments, educators devote an entire class period to each decision, to highlight the importance of the activity and encourage students to take it seriously. In addition, such a structure gives the instructor sufficient time to interact with each group individually and help them make decisions, in a strong active learning environment. The final deliverable can feature 15- to 20-minute presentations of the virtual firm to a board of trustees (i.e., the class), in which students argue for why they should remain in a leadership role, by detailing the strategies they used, their successes and failures, and what they would do differently in the future. Students also might write papers to provide deeper, research-based insights into the retail analytics they used to make their decisions. Enhanced In-Class Discussions and Breakout Groups. The digital revolution has provided retail educators with a wide array of digital options, including e-books and a host of interactive exercises. For example, starting with its eighth edition, Retailing Management has integrated McGraw-Hill’s Connect Marketing platform with the digital version, offering access to a host of retailing exercises. The ninth edition expanded the newsletter content available and provided online access to articles and videos specifically linked to each chapter topic in a blog format (www.theretailingmanagement.com). Synopses of popular press articles also offer suggested discussion questions, such that students can consider relevant, topical issues without needing to purchase subscriptions to sources such as The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal. The abbreviated length also supports the use of these synopses to stimulate active learning discussions in the classroom. For example, consider a recent article synopsis discussing Amazon’s foray into brick-and-mortar retailing, which will involve groceries, as well as showrooms for Amazon products, furniture, and appliances.2 To engage students in active learning, classes might be divided into breakout groups, each of which receives a print version of the article and related discussion questions, such as the following: 1. 2. 3. 4. How is Amazon using its technology to compete in the brick-and-mortar arena? How important is location for Amazon’s showrooms? Its grocery stores? Perform a SWOT analysis to understand the risks and benefits of Amazon opening brick-and-mortar locations. If you were the Chief Marketing Officer of Target, how would you respond to Amazon’s move? Then groups of two to four students each take about 10 minutes to read the article and consider their answers to the questions. By answering them in small groups, each student gains an opportunity to discuss and develop her or his own opinion, which enhances student engagement, classroom discussions, and learning. While the groups are discussing the concepts presented in the synopses, the educator can visit each group and provide individual comments on their insights, which establishes a scaffold for learning and provides the educator with information about students’ effective learning and areas that may need more coverage in class. After the groups finish their analyses, the class comes back together to discuss the reading as a whole. Each group has had time to analyze the reading independently, so these class discussions tend to be dynamic and diverse. Retailer Analysis. Another example assignment, assigns students to groups of two to three people, each of which chooses a retailer to analyze throughout the semester. Each week, students undertake an assignment related to the course content covered in that period (e.g., location analysis, omnichannel strategy, merchandise planning, financial strategy), such that they are required to visit a brick-and-mortar location of their chosen retailer and evaluate it according to that topic. Groups provide brief, 5-minute presentations the following week. By 90 Journal of Marketing Education 40(1) Figure 3. Example analysis of tweets by @Walmart and @Patagonia. Source. AnalyzeWords.com. limiting the presentations to a maximum of 5 minutes, this method forces students to distill their analyses into key takeaways and learn to be concise. For example, the instructions for a retailer analysis assignment that accompanies the class discussion of location analysis were the following: Go to “your store.” If “your store” doesn’t have an Internet store, choose another store for this assignment. Evaluate “your store’s” bricks and mortar assortment. Is it the best assortment for the space and trade area, that is, are they carrying the “right” depth and breadth? Why or why not? Be as specific as possible. Choose one major merchandise category and compare the store’s assortment with the assortment on its website. How does the depth compare? Should there be items in the store that are currently only on the website? If so, what would you remove from the store to make room for the Internet items? Social Media Analytics. Another form of analysis that students can undertake explicitly reflects modern trends in which customers increasingly connect with retailers and other consumers via social media networks, such as Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, and Twitter. To expose students to sentiment analysis concepts, active learning exercises are key, because they ensure those students understand social media platforms and how retailers can use them to drive traffic (e.g., Bal, Grewal, Mills, & Ottley, 2015). During in-class assignments, students can be introduced to social media analytics and NLP, perhaps through the demo website AnalyzeWords.com (see Pennebaker & King, 1999). In an example assignment, students identify the Twitter handles of two retailers with disparate brand identities, such as Walmart (@Walmart) and Patagonia (@Patagonia), then undertake a comparative analysis of tweets by each retailer (see Figure 3). As a semester-long project, students instead might work in teams to create fan pages for the retailer of their choice. They can post content on the fan page and other social media sites that they choose to create, using Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. The data analytics provided by these social media sites help students understand how different types of content (e.g., text, pictures, videos) drive traffic and engagement. Such an exercise thus provides insights into the uses of both social media and data analytics. Important Forthcoming Innovations in Retailing Technology: The Future In this section, we discuss several emerging technologies that have the potential to exert substantial effects on various facets of retailing. They also promise to become interesting discussion topics in retailing education classrooms. Artificial Intelligence Whether it is Apple’s Siri, Microsoft’s Cortana, Amazon’s Alexa, IBM’s Watson, or Alphabet’s Deep Mind, AI is being widely adopted. It already is present in the pockets of most smartphone owners. Despite its early development stage, 91 Grewal et al. retailers have begun to adapt their business models to include AI. With the recognition that customers often prefer to search on their phones rather than interact with a salesperson, Macy’s launched On Call, a mobile application that uses IBM’s Watson and smartphone location services to help customers navigate its stores (Arthur, 2016). Because it also features NLP, customers can ask questions of the app, using natural phrases in either English or Spanish. The AI-based responses then influence how customers shop in both stores and online. Product recommendation engines, physically locating items in a store, answering questions about store hours and returns, and supply chain optimization all represent realistic potential uses of AI (Grewal et al., 2017). Frontline Service Robots The retail landscape also promises to be altered by the introduction of frontline service robots. Today, robots are used extensively in large fulfillment centers; they offer the potential to replace human labor in other areas too, including frontline service. For example, retailers are experimenting with drones and driverless vehicles for deliveries (Van Doorn et al., 2017), and McDonald’s has announced that it plans to install automated kiosks in 2,500 of its stores to eliminate the need for cashiers and create the “experience of the future” (Kim, 2017). Internet of Things In the 1990s, users connected to the Internet through desktop computers and dial-up modems with slow connection speeds. But by 2009, smartphones had heavily penetrated markets and the Internet had expanded to include mobile websites and mobile applications. Technology continues to grow smaller and cheaper, enabling a host of “smart devices” connected to the Internet, including Bosch Home Connect ovens, Samsung smart washers and dryers, Nest thermostats, Ring video doorbells, SimpliSafe security system, GPS and accelerator sensors on smartphones, and radio frequency identification tags on products. When data from a multitude of Internet-connected sensors combine, the IoT emerges (Gubbi, Buyya, Marusic, & Palaniswami, 2013). Supported by decreasing storage costs, retail analytics, and advanced visualizations, IoT promises to provide a wealth of data to retailers that should help them optimize their processes. Among many other applications, they can achieve inventory optimization, predictive preventative maintenance, and distribution center efficiencies (Siebel, 2017). Students need to be aware that IoT has not only the potential to improve processes but also the potential to abuse consumer privacy. If in-home appliances gather personal data about the consumers who use them, for example, retailers have ethical responsibilities to use that data appropriately, and students should be prompted to consider such issues carefully. Blockchain/Distributed Ledger Technology Predicted to be worth $7.74 billion in the next few years, blockchain technology is poised to disrupt many industries, including retailing (Conick, 2017; Nowiński & Kozma, 2017). In its simplest form, blockchain or distributed ledger technology (DLT) is an immutable spreadsheet or ledger that is stored on thousands of computers and publicly available for anyone to search at any time (Conick, 2017). By replicating the ledger so vastly, it becomes nearly impossible for the data contained in the spreadsheet to be hacked or altered. The result is trust in the immutable data, such that data intermediaries are no longer necessary. The applications of blockchain technologies pertain to three main areas: authenticating traded goods, disintermediation, and lower transaction costs (Nowiński & Kozma, 2017). By combining blockchain and IoT technologies, retailers can track precisely where products are at any moment in the supply chain. If product provenance is important (e.g., wine, coffee), consumers can scan a quick-response code on the packaging and see the entire journey of their coffee beans, from farm to cup (Conick, 2017). Thus, DLT can affirm customers’ trust in retailers’ claims, eliminating the need for intermediaries that currently function to verify those claims. For example, in the digital advertising space, fraud is rampant today, but if they turn to DLT, retailers can eliminate intermediaries, buy ads directly, and confirm through the blockchain that their marketing communication actually took place. Being able to track products better and eliminate intermediaries promises to lower operations and transaction costs substantially, providing a compelling opportunity to increase profitability. Discussing New Technologies in The Classroom Within the classroom, educators must reinforce topics related to technology that are not yet covered in textbooks. A simple way to incorporate these concepts would be to start each class with a brief discussion of “retailing technology in the news.” These discussions can also incorporate recent retailing articles published in journals, such as Journal of Retailing. Students would bring to each class popular press retailing-related articles or academic articles pertaining to big data, analytics, robotics, blockchain, IoT, and so on. The instructor can randomly call on two to three students at the start of each class meeting, who summarize the article they read and why they think it is important to retailing. A brief class discussion then ensues, tying the article to relevant course concepts. Conclusions In the 1960s, Gordon Moore (1965), cofounder of Intel, proposed Moore’s law, which asserted that computing technology would double every 24 months—a prediction that has 92 proved surprisingly accurate. Technological revolutions have irrevocably altered the way retailers conduct business, requiring retailing textbooks and educators to update their curricula constantly to stay abreast of the latest advances. We have taken a historical view on retailing education, to highlight its past, its present, and the likely future of retailing technologies and education. One of the most notable changes in retailing textbooks is their treatment of e-tailing channels. We analyzed all 10 editions of Retailing Management, including the third edition, which followed soon after Amazon sold its first book and included a discussion of “electronic retailing” and its potential. As the importance of the online channel grew, Retailing Management altered its discussion, from the potential of electronic retailing to discussing “multichannel retailing” and how to develop retailing strategies for different channels (fifth edition). As smartphone penetration increased and consumers became untethered from their computers, retailers again had to shift their strategy, away from a multichannel approach and toward merging all of their channels into a single, seamless experience, termed omnichannel retailing. The 10th edition of Retailing Management thus discusses how retailers can develop omnichannel strategies. Just as technology has changed the retailing landscape, it has enabled innovative new approaches that retailing educators can adopt. Instead of issuing lectures based on business cases, educators can engage students and help them take responsibility for their education through active learning. We offer suggestions and summaries of several active learning activities related to different topic areas, including retailer analyses, competitive simulations, sentiment analysis, social media campaigns, and big data and privacy issues. Digital learning platforms also provide opportunities for educators to supplement their instruction, with elements such as digital textbooks, flashcards, and interactive lessons. Blogs, such as www.theretailingmanagement.com, provide short summaries of important modern retailing developments that can be distributed as mini case studies to foster classroom discussions about relevant topics. Retailing and retailing education will continue to evolve too. We note three key technological advances that educators need to follow and potentially integrate into their classes. The AI revolution may produce frontline service robots that replace human counterparts. As the number of Internetconnected products increases, the IoT will take on increased importance. Combining AI and retailing analytics, a revolution can optimize retailing strategies, including supply chain efficiency, inventory management, pricing, and perhaps even visual merchandising. As more retailers adopt blockchain technology, new levels of transparency and closer relationships with consumers are likely to emerge, with benefits and challenges that retail actors and the educators who teach about them need to address. Journal of Marketing Education 40(1) Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Notes 1. 2. The textbook was authored by Michael Levy and Barton A. Weitz from the first to eighth editions and by Michael Levy, Barton A. Weitz, and Dhruv Grewal for the ninth and 10th editions. See http://www.theretailingmanagement.com/?p=1577. References Aguirre, E. M., Mahr, D., Grewal, D., Ruyter, K. D., & Wetzels, M. (2015). Unraveling the personalization paradox: The effect of information collection and trust-building strategies on online advertisement effectiveness. Journal of Retailing, 91(1), 34-49. Ailawadi, K. L., & Farris, P. W. (2017). Managing multi- and omnichannel distribution: Metrics and research directions. Journal of Retailing, 93, 120-135. Arthur, R. (2016, July 20). Macy’s teams with IBM Watson for AI-powered mobile shopping assistant. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/rachelarthur/2016/07/20/macysteams-with-ibm-watson-for-ai-powered-mobile-shoppingassistant/#4aad3b8b7f41 Bal, A., Grewal, D., Mills, A., & Ottley, G. (2015). Engaging students with social media. Journal of Marketing Education, 37, 190-203. Bradlow, E. T., Gangwar, M., Kopalle, P., & Voleti, S. (2017). The role of big data and predictive analytics in retailing. Journal of Retailing, 93(1), 79-95. Braun, S. (2015, May 8). The history of retail: A timeline. Retrieved from https://www.lightspeedhq.com/blog/2015/05/the-historyof-retail-a-timeline/ Conick, H. (2017, November/December). What marketers need to know about blockchain. Marketing News, 12-14. Retrieved from https://www.ama.org/publications/MarketingNews/Pages/whatmarketers-need-know-about-blockchain.aspx Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 8410-8415. Grewal, D. (2018). Retail marketing management: The 5Es of retail today. Manuscript in preparation. Grewal, D., Bart, Y., Spann, M., & Zubcsek, P. P. (2016). Mobile advertising: A framework and research agenda. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 34, 3-14. Grewal, D., Roggeveen, A., & Nordfält, J. (2017). The future of retailing. Journal of Retailing, 93(1), 1-6. Gubbi, J., Buyya, R., Marusic, S., & Palaniswami, M. (2013). Internet of things (IoT): A vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future Generation Computer Systems, 29, 1645-1660. Grewal et al. Inman, J. J., & Nikolova, H. (2017). Shopper-facing retail technology: A retailer adoption decision framework incorporating shopper attitudes and privacy concerns. Journal of Retailing, 93(1), 7-28. Kim, T. (2017, June 20). McDonald’s hits all-time high as wall street cheers replacement of cashiers with kiosks. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2017/06/20/mcdonalds-hits-all-timehigh-as-wall-street-cheers-replacement-of-cashiers-with-kiosks. html Kumar, V., Anand, A., & Song, H. (2017). Future of retailer profitability: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing, 93(1), 96-119. Levy, M., & Weitz, B. A. (1995). Retailing management (2nd ed.). Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Levy, M., Weitz, B. A., & Grewal, D. (2014). Retailing management (9th ed.). Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Levy, M., Weitz, B. A., & Grewal, D. (2018). Retailing management (10th ed.). Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Mattmann, C. A. (2013). Computing: A vision for data science. Nature, 493, 473-475. McAfee, A., Brynjolfsson, E., & Davenport, T. H. (2012). Big data: The management revolution. Harvard Business Review, 90(10), 60-68. Moore, G. E. (1965). Cramming more components onto integrated circuits. Electronics, 38, 114-117. Nowiński, W., & Kozma, M. (2017). How can Blockchain technology disrupt the existing business models? Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 5, 173-188. Ordenes, V. F., Ludwig, S., Ruyter, K. d., Grewal, D., & Wetzels, M. (2017). Unveiling what is written in the stars: Analyzing explicit, implicit, and discourse patterns of sentiment in social media. Journal of Consumer Research, 43, 875-894. Pang, B., & Lee, L. (2008). Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Foundations and Trends in Information Retrieval, 2(1-2), 1-135. Pennebaker, J. W., & King, L. A. (1999). Linguistic styles: Language use as an individual difference. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1296-1312. Rafaeli, A., Altman, D., Gremler, D. D., Huang, M.-H., Grewal, D., Iyer, B., . . . Ruyter, K. d. (2017). The future of frontline View publication stats 93 research: A glimpse through the eyes of thought leaders. Journal of Service Research, 30(1), 91-99. Roggeveen, A. L., & Grewal, D. (2016). Engaging customers: The wheel of social media engagement. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(2). doi:10.1108/JCM-12-2015-1649 Roggeveen, A. L., Grewal, D., Townsend, C., & Krishnan, R. (2015, November). The impact of dynamic presentation format on consumer preferences for hedonic products and services. Journal of Marketing, 79, 34-49. Roggeveen, A. L., Nordfält, J., & Grewal, D. (2016). Do digital displays enhance sales? Role of retail format and message content. Journal of Retailing, 92, 122-131. Siebel, T. M. (2017, December). Why digital transformation is now on the CEO’s shoulders. McKinsey Quarterly. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/digital-mckinsey/our-insights/why-digital-transformation-is-now-on-theceos-shoulders Stone, B., & Boyle, M. (2017, May 4). Can Wal-Mart’s expensive new e-commerce operation compete with Amazon? Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/ news/features/2017-05-04/can-wal-mart-s-expensive-new-ecommerce-operation-compete-with-amazon Van Doorn, J., Martin, M., Noble, S. M., Hulland, J., Ostrom, A. L., Grewal, D., & Petersen, J. W. (2017). Domo Arigato Mr. Roboto: Emergence of automated social presence in organizational frontlines and customers’ service experiences. Journal of Service Research, 20(1), 43-58. Wingfield, N., & de la Merced, M. J. (2017, June 16). Amazon to buy Whole Foods for $13.4 billion. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/16/business/dealbook/ amazon-whole-foods.html Witcher, B., Swerdlow, F., Gold, D., & Glazer, L. (2015). Mastering the art of omnichannel retailing. Retrieved from https://www. forrester.com/report/Mastering+The+Art+Of+Omnichannel+ Retailing/-/E-RES129320. Woodham, O. P. (2017). Testing the effectiveness of a marketing simulation to improve course performance. Marketing Education Review. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/ 10528008.2017.1369356