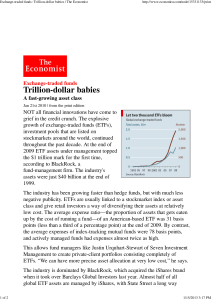

Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs 1. What is an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF)? 1.1 Introduction Exchange-traded Funds (ETFs) have multiplied in size and number since they were first introduced in 1993. As of December 2018, there were more than 6,000 publicly traded EFTs globally (see in Figure 1).1 The estimated combined value of these ETFs is over $5 trillion. There are approximately 2,800 ETFs listed on US exchanges with a total estimated value of $3.85 trillion. These investment vehicles now rival publicly traded stocks for investors’ attention. For comparison, the Wall Street Journal 2 reported that there were only 3,671 publicly traded stocks on US exchanges in 2017, down from 7,322 in 1996. The reduction in publicly traded companies is attributed to mergers, acquisitions, and a decline in Initial Public Offerings (IPOs). Figure 1 - Total Publicly Traded ETFs 2003 - 2018 1 2 statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/278249/global-number-of-etfs/, sourced January 2, 2020. Thomas, Jason M., Where Have All the Public Companies Gone?, Wall Street Journal, Nov. 16, 2017. 1 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs ETFs crowding out individual stocks, coupled with the lack of IPOs, is potentially detrimental for individual investors. In the past, many of the the growth companies that went public needed to so because the only place they could raise sufficient amounts of new capital was in public markets. But that is not the case any longer as private equity groups and venture capitalist are now able to provide sufficient capital to allow private growth companies to reach considerable sizes before they have to go public. And when they do, the IPO is often more of a liquidation event (i.e. insiders and early investors cashing out) than a capital raise. Consider Amazon and Facebook; Amazon was taken public for $600 million just three years after Jeff Bezos founded it, while Mark Zuckerberg didn’t take Facebook public for eight years after its creation. Facebook’s IPO resulted in a market value of $100 billion for the company. ETFs are not just replacing individual stocks in investor’s portfolios; they were initially intended to supplant mutual funds as the go-to alternatives for investors willing to manage their own portfolios. By taking on this task, the do-it-yourself investors can avoid the 2% fees charged by the average mutual fund, but must be willing assume the duties of the investment decisions. The ETF structure facilitates portfolio management by providing3: 1) Access: ETFs allow individual investors to build sophisticated portfolios through strategic allocations in all asset classes in a manner similar to those used by institutional investors and portfolio managers; 2) Transparency: Because most ETFs report their portfolio positions frequently during the day and at the end of the trading day, individual investors can quickly and reliably determine what is in inside the portfolios they own; 3) Liquidity and Price Discovery: Because trading may be irregular or disrupted in many markets of interest to individual investors, ETFs can provide liquidity and price discovery. For example, many parts of fixed income markets and less liquid parts of US equity markets are more easily accessed through ETFs, that allow individual investors to easily get into and out of these markets and afford some degree of diversification across a specific asset class. The ability to access foreign stock markets quickly and inexpensively is also an important advantage of ETFs, especially when trading disruptions occur in these markets or when foreign investors are constrained through capital controls or outright exclusions to direct investing. 4) 4) Tax efficiency: Because ETFs can be arbitraged through in-kind exchanges (more on this later), they are less exposed to capital gains taxes relative to mutual funds and other investment vehicles. These tax savings are passed on to ETF investors. 3 Hill, J. M, D. Nadig, and M Hougan, A Comprehensive Guide to Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), CFA Institute research Foundation, 2015. 2 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs 1.2 What is an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF)? Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are investment vehicles introduced in US markets in 1993 to compete directly with mutual funds and other similar investment vehicles. They are simply (unmanaged or managed) portfolios of securities related to an investment theme or strategy that are publicly traded like stocks. They can be sector specific, industry specific, country specific, investment style specific, etc. As of early 2020, there are thousands of publicly traded ETFs. Table 1 presents a partial breakdown of various ETF choices based on asset classes, sectors, and other general categories such as country, region, investment style, and asset class size. Table 1 – ETF counts by classifications Asset Classes # of ETFs Alternatives 37 Bond 408 Commodity 117 Currency 35 Equity 1576 Multi Asset 95 Preferred Stock 12 Real Estate 50 Volatility 24 Total 2354 Sectors Consumer Discretionary Consumer Staples Energy Financials Healthcare Industrials Materials Real Estate Technology Telecom Utilities Total Source: ETFdb.com # of ETFs 37 28 82 58 57 37 59 51 80 9 25 523 Other (sub category counts) Industry Specific (80) Regional (14) Country (71) Bonds (30) Commodity (31) Natural Resources (7) Currency (12) Alternatives (5) Multi Asset (5) Volatility Investment Style (20) Asset Class Size (6) Asset Class Style (3) Asset Class Size and Style (17) Inverse (7) Leveraged (7) # of ETFs 523 3089 2898 816 122 117 35 37 90 18 2659 1728 1700 1700 122 239 3 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs Another source provides a count of all publicly traded ETFs and other exchange traded products (ETPs) by country. As you can see, there are almost 9,000 investment vehicles available to individual investors to facilitate unique portfolio combinations and strategies. Table 2 – ETFs and ETPs by County 4 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs 1.3 How ETFs Shares Are Created and Redeemed ETFs combine important characteristics of closed-end funds (CEF) and mutual funds. Similar to CEFs, ETF shares are traded intraday on exchanges, providing liquidity for interested investors. Similar to mutual funds, ETF shares can be created or redeemed at the end of the day. Thus, the size of the fund can increase and decrease depending on investor demand. However, the redemption process for ETFs differs from that of mutual funds in two important ways. First, end of day redemptions occur between the ETF Distributor and Authorized Participants (AP)4, who have exclusive agreements for end of day trading. Second, in many ETFs, primary trades occur in-kind (i.e. and exchange of securities) and do not require cash-based security purchases or sales by the ETF. Note that most active APs act as agents to facilitate creation or redemptions on behalf of their clients. Furthermore, the roles of APs and market makers are different, but some firms act as both an AP and a market maker for a given ETF. The creation of new shares and the redemptions of existing shares are generally initiated by market makers who engage an AP when there is an imbalance of orders to buy or sell ETF shares that cannot be met through the secondary market (individual investors transacting with the market makers). Before the market opens for trade, an ETF will report current fund holdings and will identify which securities are in the basket (i.e. portfolio of securities reflecting the ETF’s holdings) that the ETF will accept for creations or deliver for redemptions on that day. The exchanges between an ETF and an AP are typically in-kind if the ETF is based on stocks or bonds. Figure 2 illustrates the flow of the transactions for ETF share creation. The AP delivers a basket of securities in exchange for ETF shares. The ETF shares are then exchanged with the market maker in return for cash or securities related to the holdings of the ETF. Likewise, if a large institutional investor wished to buy a block of ETF shares they may deliver cash to the AP, who in turn delivers securities to the ETF in exchange for ETF shares, which are then delivered to the investor. Figure 2 - ETF Share Creation 4 Examples of US Authorized Participants include ALPS, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, BNP Paribas, BNY Mellon Capital Markets, Cantor Fitzgerald Solutions Group, Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, GTS, Jeffries, JP Morgan, KCG, Mizuho Securities USA, Morgan Stanley, Susquehanna International Group, UBS Securities, Virtu Financial, and Wells Fargo Securities. 5 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs Figure 3 illustrates the flow of the transactions for ETF share redemptions – which is the reverse of the creation process. Here, market makers will exchange ETF shares with the AP in return for cash or securities. The AP, in turn transacts with the ETF by giving up ETF shares in return for securities held by the ETF. Similarly, if ETF shares are trading above their fair value, and investor may want to sell its holdings of those shares. Following the same process, the AP will exchange those shares with the ETF and deliver cash or securities to the investor. Figure 3 - ETF Share Redemption In addition to providing low cost and transparent trading, this process encourages arbitrage. If ETF share values deviate too far from the combined values of the underlying securities held in the ETF portfolio, market makers and institutional investors can step in an make quick profits by trading through this mechanism. Finally, as indicated in Table 1, there are typically dozens of designated APs for each ETF, ensuring that EFT share prices cannot stray too far from their intrinsic values (note that on average only 5 APs are active for a given ETF). However, APs are not obligated to create or redeem ETF shares, which means that in volatile markets, ETF share prices have the potential to deviate materially from intrinsic value. Table 1: Mean Authorized Participants for ETFs5 by Size and Type Size ($ million) Mean # of APs ETF Type 790 and above 38 Emerging Markets Bonds 158 to 790 36 Domestic High-Yield Bond 27 to 158 33 Emerging Markets Equity Under 27 31 International Equity Domestic Equity All 34 All Mean # of APs 29 30 35 35 35 34 5 Antoniewicz, R. and J Heinrichs, The Role and Activities of Authorized Participants of Exchange-Traded Funds, Investment Company Institute, 2015 6 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs 1.4 How ETFs Shares Are Created and Redeemed – SPDR Gold Trust (GLD) Example6 The SPDR Gold Trust is the largest non-equity, non-bond ETF with over $46 billion in market capitalization and average trading volume of over 7.3 million shares daily.7 Shares of this trust trade on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) under the symbol GLD. The trust’s holdings are comprised solely of gold bullion; therefore, the shares are designed to reflect the price of gold as closely as possible. This means that the value of the shares will fluctuate with the price of gold. This in turn means, that GLD is a suitable vehicle for hedging and speculation. As of June 30, 2019, the Custodian for the trust held 25,651,752 ounces of gold on behalf of the trust in the form of London Good Delivery gold bars with a market value of $36.1 billion. Primary market participants for GLD include: § § § § BNY Mellon Asset Servicing (The Trustee), which is responsible for the day-to-day administration of “the Trust” (i.e. the Fund). HSBC Bank plc (The Custodian), which stores Good Delivery gold bars for the Trust in London. World Gold Trust Services, LLC, (The Sponsor) a subsidiary of the World Gold Council, which oversees the performance of the Trustee and the Custodian. The Authorized Participants, which include Credit Suisse Securities (USA) LLC, Goldman Sachs & Co., Goldman Sachs Execution & Clearing, L.P., HSBC Securities (USA) Inc., J.P. Morgan Securities LLC, Merrill Lynch Professional Clearing Corp., Morgan Stanley & Co. LLC, RBC Capital Markets, LLC, UBS Securities LLC, and Virtu Financial BD LLC. The price of GLD is determined by market supply and demand and reflected on the exchange where it’s traded (NYSE Arca), just like the spot gold price is determined by the supply and demand of gold in the London Bullion Market. One GLD share represents 0.1 ounce of gold. Therefore, the market value of one GLD share should be equal to the value of 0.1 ounce of gold (with small deviations throughout the trading day). If the price differences get too large, the APs (or clients) will arbitrage that difference to make a riskless (almost) profit and force the prices of gold and GLD back into equilibrium. For example, if the price of GLD trades at a premium to the price of gold, an Authorized Participant (AP) can buy gold, deposit the gold at the Trustee, which then creates shares in return for the AP, who can then sell these on the stock market. This process will drive up the gold price and lower the price of GLD. APs will continue the arbitrage process until the gap is closed. See Figure 4 for an illustration of the process. 6 Much of the information for the section is presented in the prospectus for the SPDR Gold Trust found at https://www.spdrgoldshares.com/media/GLD/file/SPDR-Gold-Trust-Prospectus-20190908.pdf 7 ETFdb.com, sourced on Feb 7, 2020 at https://etfdb.com/compare/market-cap/ 7 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs GLD securities can only be created or redeemed in a “Basket” of 100,000 shares. Because one share represents 0.1 ounce, 10,000 fine troy ounces (about 25 Good Delivery bars) are required for creating 100,000 shares of the Trust. Likewise, 100,000 shares are required for redeeming (withdrawing) 10,000 fine troy ounces from the Trust. The day GLD was launched, one share represented 0.1 ounce. Currently, one share represents 0.094 ounce. The difference arises because over time small amounts of the Trust’s gold are sold to pay for the Custodian’s storage fees and the Trustee’s expenses. This gradual, but continuous, selling is the reason that one GLD share now represents somewhat less than 0.1 ounce of gold, and this difference will continue to grow over time. As a consequence, APs currently need to deposit less than 10,000 ounces at the Trustee in order to create 100,000 shares, and will receive less than 10,000 ounces when redeeming 100,000 shares. Figure 4 - SPDR Gold Trust (GLD) ETF Share Creation Naturally, the arbitrage works the other way around when GLD trades at a discount to the gold price. In this situation, APs will redeem shares at the Trustee in exchange for gold that they can sell in the London Bullion Market. See Figure 4 for an illustration of the process. Figure 5 - SPDR Gold Trust (GLD) ETF Share Redemption 8 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs 2. What is an Exchange Traded Note (ETN)? An ETN is an unsecured debt obligation that tracks the performance of certain market indexes; it is not a managed fund like an ETF. Unlike typical debt securities, ETNs do not pay interest. They track the total return of markets, so investors receive whatever the total return of the market is, minus fees. The issuer of the note is responsible for maintaining counterbalancing hedges to ensure it can meet its obligations to investors. This risk management function is essential because ETNs have the largest potential counterparty risk of all exchange-traded products (ETPs) due to their being unsecured debt notes. In this regard they are similar to corporate bonds, but because they are unsecured, they could lose all of their value if the issuer were to go bankrupt (i.e. investors are subject to the issuer’s business risk). For example, when Lehman Brothers defaulted in 2008, the three ETNs it had issued lost almost all their value. Notably, because ETNs are unsecured debt obligations of the institution that issues them, investors holding ETN securities have no voting rights (again similar to corporate debt). In a similar vein, an ETN issuer may halt creation and redemptions of baskets if it does not wish to change or add to the debt on its balance sheet related to the index on which the ETN is based. For example, in 2012 the ETN issuer that created VelocityShares 2X VIX Short-term ETN (TVIX) decided to halt creations of baskets for several weeks. ETNs offer two distinct advantages in exchange for this counterparty risk. First, ETNs can be structured to provide access to unique areas of the markets not readily available to most investors. This is often accomplished with zero tracking error (i.e. the index returns are easily matched by the ETN issuer). The second advantage relates to taxation. Even though ETNs trade like ETFs on a stock exchange, they are not taxed like ETFs. That is an important distinction. Currently, the IRS considers ETNs to be prepaid forward contracts. Therefore, there are no dividends or interest to be taxed as regular income and a long-term investor may experience materially better tax treatment upon the sale of the ETN shares. Additionally, unlike mutual funds and some ETFs, ETNs never pay out capital gains which relieves the ETN holder of another potential source of taxation. 9 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs 3. Considerations for Selecting the “Right” ETF or ETP 3.1 Efficiency Considerations When considering an investment in ETFs, the investor should pay attention to the all of the costs associated with managing the fund, including: the expense ratio, tracking error, tax issues, trading costs, and bid-ask spreads, and premia and discounts. We will explore each of these next. Expense Ratios: Expense ratios for ETFs tend to be lower, and sometimes much lower, than those for mutual funds competing with similar strategies. In either case, expense ratios are a function of the strategy of the ETF (or mutual fund) and can vary widely. For example, as indicated by the figures in Table 3, the expense ratios for US Fixed Income strategies average 0.25% while those for US Equities are closer to 0.50%. The higher risk strategies (i.e. Alternatives, Inverse, and Leverage) all have the highest expense ratios. Table 3 – Expense Ratios by Asset Class (2014) Source: ETF.com and The CFA Institute Research Foundation 10 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs Tracking Error: Tracking error refers to the difference between an EFT’s performance record and that of its benchmark. For example, suppose a fund tracking the S&P 500 reported a return of 11.27% for a particular year. If the actual index reported a return of 11.68%, the tracking error would be 0.41% (11.68% - 11.27%). Note that professionals often measure ETF tracking error on a daily basis, but this is unnecessary. Also note that tracking error is a function of the management fees, so one can think of this metric as measuring relative management performance and the cost of doing so combined. Therefore, two ETFs with similar management fees may have very different relative performance compared to the benchmark. Finally, funds that consistently underperform their benchmark should be avoided. Tracking error can also be caused by changes to the underlying index securities, volatility in the EFT’s asset class of broader market, regulatory or tax requirements, non-management fees and other expenses incurred by the fund, and artificial tracking error that arises if funds managers have to place a value on illiquid securities held by the fund. These securities may not report prices every day. Tax Issues: Investors need to be aware of capital gains distributions when investing in tradable funds. All mutual funds must distribute realized capital gains in the year that they are captured, and these gains are passed on to fund holders. However, the timing of the distributions (often at year end) may benefit some fund investors (those that exited their position before the distribution) and penalize others (those that may not have held the fund for the full year but suffer the tax consequences of the distribution). Unlike mutual funds and other funds, ETFs typically exchange baskets and shares (see sections 1.3 and 1.4). This activity is called an in-kind exchange and does not create a tax obligation. Furthermore, most ETFs are index funds and have significantly lower turnover that active strategies. Finally, the in-kind exchange mechanism means that ETFs (unlike mutual funds) do not have to sell appreciated securities to provide liquidity to APs, they simply exchange securities. Finally, ETFs are taxed based on one of five underlying regulatory structures: open-end fund, unit investment trust, grantor trust, limited partnership (LP), or exchange-traded note (see section 2). Because tax laws are constantly changing, it is important to know your ETFs structure and how it is taxed. Trading Costs: This is a cost in addition to management fees, and comprise commissions paid to brokers to enter and exit positions. Because index ETFs do not engage is a lot of trading, their costs will be relatively low. However, actively managed ETFs will experience higher trading costs. 11 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs Bid-Ask Spreads: This is a cost related to the supply and demand for the particular ETF or ETP, as well as the underlying securities held by the ETF. It is also a function of the liquidity (i.e. how many shares actually trade on an average day). Lack of supply or demand (i.e. lack of transaction liquidity) means that the bid-ask spread will be wider on average and impose higher costs on investors. Table 4 presents median bid-ask spreads for ETF by strategy. Typically these costs are more of a concern for frequent traders than for buy-and-hold-investors. Table 4 – Median ETF Bid-Ask Spreads as of March 2014 Source: ETF.com and The CFA Institute Research Foundation Premiums and Discounts: Every ETF publishes its Net Asset Value (NAV) at the end of the day (4p.m. New York time), but they also publish an estimate of their NAV intraday (as frequently as every 15 seconds). For some ETFs, this frequent NAV quote will keep premia and discounts relatively small throughout the trading day. For others, the deviations away from NAV may relatively large. For example, the SPY is an ETF that tracks the S&P 500 index, which is composed of U.S. listed stocks that trade in liquid markets throughout the day. There is very little change to material mispricing because of the liquidity and depth of the markets for the individual securities and for the SPY. 12 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs However, an ETF specializing in exposure to China will have much more difficulty offering a NAV estimate. In this case, differences between the value of the underlying portfolio and the ETF can arise due to different exchange trading hours that do not overlap (when New York is trading China is not, and vice versa), and the inability of western investors to directly hold A-shares traded in China on the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE). Because the ownership may be indirect (or derivative) and the time zone differences, the ETF would offer an INAV (intraday NAV). Furthermore, even if a foreign-focused ETF held shares that traded on exchanges whose trading hours coincide with those of New York (e.g. Canada and Mexico), currency fluctuations would increase the difficulty of providing a precise INAV. Therefore, premia and discounts for these kinds of ETFs may be larger than one might expect. But note that as soon as it becomes profitable to arbitrage, APs are likely to do so and bring the ETF value back into equilibrium. Another situation where premia and discounts may become large is when there is material demand or supply for the ETF shares. For example, between March 30, 2009 and March 31, 2014, HGY traded at a premium and a discount as large as 6.6% and 3.6, respectively. The deviations away from the NAV for HYG are presented in Figure 6. Figure 6 – HYG Premium vs. Net Inflows Source: The CFA Institute Research Foundation 13 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs Another potential complication is market dislocations. For example, during the Arab Spring in 2011, local disturbances in Egypt caused its stock market to close. However, shares in the ETF EGPT continued to trade in New York. Even though APs were not allowed to trade with the ETF during this time (i.e. no arbitrage), the value per share of the ETF’s provided some indication of the perceived value of the stocks held by EQPT. In this case, EQPT traded at large premiums (over 3%) for several weeks until the Egyptian stock market reopened. 3.2 Risk Risk is often defined as the volatility of a securities market price over a specific time period. However, an investor should also consider other sources of risk when considering an investment in specific ETFs. Fortunately, funds and publicly traded companies are required to provide a risk assessment in their annual filings. For example, the prospectus for GLD includes the following information about risks related to the value of GLD shares:8 The Shares are designed to mirror as closely as possible the performance of the price of gold, and the value of the Shares relates directly to the value of the gold held by the Trust, less the Trust’s liabilities (including estimated accrued expenses). The price of gold has fluctuated widely over the past several years. Several factors may affect the price of gold, including: • • • • • • • Global gold supply and demand, which is influenced by such factors as gold’s uses in jewelry, technology and industrial applications, purchases made by investors in the form of bars, coins and other gold products, forward selling by gold producers, purchases made by gold producers to unwind gold hedge positions, central bank purchases and sales, and production and cost levels in major gold-producing countries such as China, the United States and Australia; Global or regional political, economic or financial events and situations, especially those unexpected in nature; Investors’ expectations with respect to the rate of inflation; Currency exchange rates; Interest rates; Investment and trading activities of hedge funds and commodity funds; and Other economic variables such as income growth, economic output, and monetary policies. The Shares have experienced significant price fluctuations. If gold markets continue to be subject to sharp fluctuations, this may result in potential losses if you need to sell your Shares at a time when the price of gold is lower than it was when you made your investment. Even if you are able to hold Shares for the long-term, you may never 8 SPDR Gold Trust 14 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs experience a profit, since gold markets have historically experienced extended periods of flat or declining prices, in addition to sharp fluctuations In addition, investors should be aware that while gold is used to preserve wealth by investors around the world, there is no assurance that gold will maintain its long-term value in terms of purchasing power in the future. In the event that the price of gold declines, the Sponsor expects the value of an investment in the Shares to decline proportionately. Of course, some of these descriptions of risk are better than others. But if an investor wishes to understand the investment vehicle they are considering for addition to their portfolio, even small amounts of information can be helpful. Additionally, when investing directly in stocks, an investor can read the risk paragraphs for several stocks or peers to get a much better idea regarding industry risk, the exposure of each of the peers to this risk, and how each peer hedges or manages the risk. 15 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs 4. Portfolio Construction, Management and ETF Strategies There are two general ways to think about constructing a portfolio: The top-down method and the bottom-up method (see figure 7). The top down method begins with long-term risk and return objectives in mind. Portfolios are constructed by first considering and selection asset classes suitable for the portfolio. Next, the allocation decision will determine target proportions for equity investments, fixed income (i.e. bonds) investments, cash, and any other asset class that is appropriate and consistent with the portfolio objectives. Once target allocations are determined, the portfolio manager will continue to refine investment choices within each of the general asset classes. For example, with equities the manager will need to determine how much capital will be allocated to the domestic economy and how much will be invested abroad. Furthermore, allocation choices among market capitalization (large caps, midcaps, and small-caps), growth and liquidity, sector weighting, etc. are made. Likewise, with the fixed income allocation, the manager will need to decide how much to allocate to government bonds, investment grade corporate debt, high-yield corporate debt, international debt, municipal debt, and maturities (or more specifically duration) associated with each of these sub-classes. 4. 2. Sub-asset For equities: growth, income, Allocation large cap, small cap, international, country specific, etc. For fixed income: government debt, corporate debt, investment grade, high yield, international, duration, etc. 3. 3. Active / Passive Choosing between actively Balance managed portfolios (self or pro) and passively (e.g. index funds) managed portfolios (self or pro) 2. 4. Manager / Fund Considerations: performance, Selection costs, liquidity, taxes 1. Bottom Up Portfolio Construction Top Down Portfolio Construction Figure 7 – The Portfolio Construction Process 1. Asset Choosing between general asset Allocation classes, e.g. Equities, Fixed Income, Real Assets, Cash 16 Ferraro’s Notes on ETFs and ETNs If other asset classes are used, then additional allocation decisions to the sub-classes are also required. Examples of other asset classes include real estate (e.g. REITs invested in hotels, warehouses, office buildings, medical buildings, server farms, etc.), currencies (major currencies include the Euro, Yen, British Pound, Swiss France, Australian Dollar and the Canadian Dollar), or commodities (oil, natural gas, gold, silver, wheat, soy beans, etc.). The third step in the top down process is deciding whether the portfolio will be actively managed or passively managed. Active management means the portfolio manager is making buy and sell decisions often, and is looking for undervalued or overvalued securities and trying to time the market. Another form of actively managed portfolios is populating the portfolio with actively managed ETFs. The alternative is passive management where the manager is engaged in infrequent rebalancing decisions using index ETFs. Finally, specific decisions need to be made regarding who is to be the manager. If the portfolio is self-managed, then the ETF picking falls to the owner of the portfolio. Of course, the cost and performance of professional management should always be considered. Bottom-up portfolio construction is more opportunistic. That is, the portfolio holdings are a result of market-timing decisions and decisions related to over and undervaluation. This approach will often result in higher portfolio turnover and/or rebalancing. Note that this approach should also be coupled with well-defined risk and return objectives. 17