DOI: 10.1111/1475-679X.12174

Journal of Accounting Research

Vol. 55 No. 5 December 2017

Printed in U.S.A.

Does Corporate Social

Responsibility (CSR) Create

Shareholder Value? Evidence from

the Indian Companies Act 2013

H A R I O M M A N C H I R A J U∗ A N D S H I V A R A M R A J G O P A L†

Received 6 October 2015; accepted 4 March 2017

ABSTRACT

In 2013, a new law required Indian firms, which satisfy certain profitability,

net worth, and size thresholds, to spend at least 2% of their net income on

corporate social responsibility (CSR). We exploit this regulatory change to

isolate the shareholder value implications of CSR activities. Using an event

study approach coupled with a regression discontinuity design, we find that

the law, on average, caused a 4.1% drop in the stock price of firms forced

to spend money on CSR. However, firms that spend more on advertising

are not negatively affected by the mandatory CSR rule. These results suggest

that firms voluntarily choose CSR to maximize shareholder value. Therefore,

∗ Department of Accounting, Indian School of Business; † Roy Bernard Kester and T.W.

Byrnes Professor of Accounting and Auditing, Columbia Business School.

Accepted by Douglas Skinner. We thank an anonymous referee, Yakov Amihud, Bernie

Black, Sanjay Kallapur, Simi Kedia, Yongtae Kim, Bill Kross, Stephanie Larocque (discussant),

Suresh Radhakrishnan, Srini Rangan, Sri Sridharan, K.R.Subramanyam, Stephan Zeume (discussant), Hao Zhang, and workshop participants at 2015 MIT Asia Conference in Accounting, 2015 AAA conference and the Indian School of Business for helpful comments. We also

thank Ranjan Nayak and Aadhaar Verma for providing excellent research assistance. Finally,

we thank our respective schools for financial support.

1257

C , University of Chicago on behalf of the Accounting Research Center, 2017

Copyright 1258

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

forcing a firm to spend on CSR is likely to be sub-optimal for the firm with a

consequent negative impact on shareholder value.

JEL codes: M14; M40; M41; M48

Keywords: CSR; shareholder value; Indian Companies Act 2013

1. Introduction

Spending on certain forms of corporate social responsibility (CSR) is now

mandatory in India.1 Clause 135 of the Companies Act (mandatory CSR

rule, hereafter) passed by the Indian Parliament in 2013 requires a firm,

which meets certain thresholds in any fiscal year, to spend 2% of its average

net profits of the prior three years on CSR activities.2 A legislative mandate

forcing corporations to spend funds on CSR activities is perhaps the first of

its kind in the world. We exploit this unique setting to isolate the impact of

CSR on shareholder value.

There are two competing views on whether CSR affects shareholder

value. The “shareholder expense” view, advocated most notably by Milton

Friedman [1970], asserts that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” He goes on to argue that “if businessmen do have a social responsibility other than making maximum profits for stockholders,

how are they to know what it is? Can self-selected private individuals decide

what the social interest is?” Under Friedman’s framework, CSR activities of

a firm are typically viewed as a manifestation of moral hazard toward the

shareholder. The contrasting view, labeled here as the “stakeholder value

maximization” view, following the “doing well by doing good” theory advanced in the management literature, argues that strategic CSR spending

can increase firm value. The intuition is that a firm’s self-interested focus

on stakeholders’ interests increases their willingness to support the firm’s

operations in several ways (Kitzmueller and Shimshack [2012]).

Existing empirical evidence on whether CSR creates shareholder value

is inconclusive, partly because these studies are clouded by methodological concerns such as potential endogeneity, reverse causality, or omitted

variable problems (Margolis, Elfenbein, and Walsh [2009]).3 The choice

to conduct CSR is voluntary. Assuming firms spend their optimal level of

1 While the term CSR itself is not defined in the Indian Companies Act 2013, the Act does

provide a list of activities that it considers to be CSR. We provide these details in section 3.1.

2 As per the mandatory CSR rule, if during any fiscal year a firm has either (1) a net worth

of Indian Rupees (INR) 5,000 million (about U.S. $83 million) or more; (2) sales of INR

10,000 million (about U.S. $167 million) or more; or (3) a net profit of INR 50 million (about

U.S. $0.83 million) or more, it is required to spend 2% of its average net profits of the last

three years on CSR related activities. An exchange rate of 60INR = 1US$ is assumed for the

conversion of INR to US$.

3 For reviews of the literature on CSR, see Griffin and Mahon [1997], Orlitzky and Benjamin

[2001], Margolis and Walsh [2003], Orlitzky, Schmidt, and Rynes [2003], Margolis, Elfenbein,

and Walsh [2009], and Kitzmueller and Shimshack [2012].

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

1259

CSR, on average, there ought to be no association between future firm

performance and CSR in the cross-section (Himmelberg, Hubbard, and

Palia [1999]). Hence, it is difficult to ascertain whether the observed associations between CSR and firm performance (i) are causal in nature;

or (ii) are merely attributable to model misspecification due to the influence of unobserved firm level heterogeneity related to CSR (Himmelberg,

Hubbard, and Palia [1999]). Second, as highlighted by Hong, Kubik, and

Scheinkman [2012], reverse causality can drive the results as firms that are

doing well, and are hence less financially constrained, are more likely to

spend resources on CSR activities. Hence, firm performance could cause

higher future CSR, as opposed to the other way around. Third, as Lys,

Naughton, and Wang [2015] suggest, CSR could merely signal and not

cause future profits. In sum, the correlation between CSR and firm value or

firm performance, documented by earlier studies, albeit interesting, does

not necessarily warrant a causal interpretation.

To partially overcome these inferential problems, we exploit numerical

thresholds specified in the mandatory CSR rule and employ a regression

discontinuity design (RDD) to identify a potentially causal link between

CSR and firm value.4 An RDD typically compares the outcomes just above

and just below a discontinuous threshold, and attributes any differences

in the outcome variable to the intervention that creates the discontinuity,

assuming that but for the intervention, firms above and below the threshold are similar.5 Because the intervention is exogenously imposed, firms

have no control as to whether they will receive the intervention or not.

Hence, there is an equal probability that the firm might be assigned on either side of the threshold, thereby making RDD a close approximation of

a randomized experiment near the threshold (Lee and Lemieux [2010]).

However, an important limitation of RDD is that it captures treatment effects localized around the threshold and hence the results are not always

generalizable to the entire population.

In this paper, the discontinuity arises because, around the INR 50 million profit threshold exogenously determined by the mandatory CSR rule,

a minor change in net income leads to a discrete change (i.e., a discontinuity) in the application of CSR rule. Such discontinuity classifies firms as

AFFECTED (those who are required to comply with CSR rule) and UNAFFECTED (those who are not required to comply with CSR rule). Intuitively,

there is no reason to expect systematic differences in a firm with a net income of INR 51 million and another with a net income of INR 49 million.

Thus, any differences in the cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) around

4 Gow, Larcker, and Reiss [2016] document an increasing trend in the use of quasiexperimental methods to draw causal inference in accounting research and believe that papers using these methods are considered stronger research contributions.

5 See Imbens and Lemieux [2008], Lee and Lemieux [2010], and Robert and Whited

[2012] for recent overviews on the RDD methodology and surveys of RDD applications in

the economics and finance literature.

1260

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

the significant CSR event dates (the outcome variable in our setting) for

firms that are just above the threshold and have to comply with the CSR

requirement and those that are just below the cutoff and did not have to

comply, can be attributed to the CSR rule. Hence, our setting enables us to

draw more reliable causal inferences on the impact of CSR on firm value.

Ex ante, it is difficult to predict the impact of the mandatory CSR rule on

shareholder value. In situations where firms’ CSR activities are not aligned

with their shareholder’s interests (as suggested by Friedman [1970], Tirole

[2001], Benabou and Tirole [2010], and Cheng, Hong, and Shue [2013]),

the new mandatory CSR rule, via its increased reporting and governance

requirements, will likely force firms to redirect their CSR spending to maximize firm value, leading thus to an increase in the shareholder value

of firms affected by the rule. For instance, the increased scrutiny under

mandatory CSR can force managers to cultivate relations with stakeholders

that would pay off in the long run. However, if firms already conduct CSR

to maximize their firm value before the law was passed, imposing binding

legal constraints on their CSR choices will lead to declines in their shareholder values (Demsetz and Lehn [1985]). For example, if at equilibrium,

a firm’s marginal benefits of CSR are lower than the marginal costs of CSR,

then the firm will not spend on CSR. In such a case, requiring such a firm to

spend 2% of its profits on CSR will only lead to a reduction of shareholder

value.

To test these predictions, we examine CAR of AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED firms around eight important event dates underlying the legislative passage of the mandatory CSR rule. Our main finding is that around

these significant events, CAR for the AFFECTED firms is lower than the CAR

for UNAFFECTED firms, suggesting an economically significant negative relation between CSR and shareholder value. We find that, on average, firms

that are forced to spend money on CSR experience a 4.1% drop in the stock

price around the eight events. Given that firms are required to spend 2% of

their profits on CSR, to the extent CSR-related activities are negative NPV

projects, the passage of this rule is likely to result in a 2% decline in shareholder value—corresponding directly to cash outflows of CSR activities. Although the 4.1% decline in shareholder value is not statistically different

from 2%, interviews with CFOs of some of our sample firms suggest that the

decline in shareholder value beyond 2% is plausible on account of factors

such as the stock market’s perception of increased Governmental interference in business, increased compliance costs associated with reporting and

monitoring CSR activities, and/or the diversion of scarce managerial time

and effort to CSR activities that do not add to shareholder value.6

We then perform three cross-sectional analyses to identify conditions under which the mandatory CSR rule is likely to affect firm value differentially.

6 We hasten to add that we cannot empirically disentangle the impact of these conjectures

on shareholder value.

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

1261

These predictions are motivated by the “stakeholder value maximization”

perspective of the management literature. Specifically, we examine whether

the impact of CSR on shareholder value varies depending on the firm’s political connections, its advertisement spending, and its affiliation to a highly

polluting industry. We find that the CAR for AFFECTED firms is less negative

if such firms advertise. This is consistent with Servaes and Tamayo [2013]

who argue that CSR and firm value are positively related for firms with high

consumer awareness, as proxied by advertising expenditure. However, we

find no consistent results for cross-sectional variation in stock price reactions to the mandatory CSR rule for AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED firms

when we partition firms on political connectedness or on their membership in a polluting industry.

We also examine whether the mandatory CSR rule impacts long-term

value of the AFFECTED firms using Tobin’s Q as a measure of firm value. If

investors consider CSR activities to be detrimental to firm value, then the

Q of the affected firms should decline more, relative to that of unaffected

firms, in the years when the likelihood of the passage of mandatory CSR

rule increased. Consistent with our expectations, we find a greater decline

in the Q of the AFFECTED firms in the years 2011 and 2013 relative to the

Q of the benchmark UNAFFECTED firms.

Overall, our results suggest that, on average, the mandatory CSR rule imposes significant net costs on firms that are required to comply with this

regulation, leading to declines in shareholder value. We perform several

additional tests to check the sensitivity of our results. First we test the basic

assumption of RRD that firms should not be able to manipulate the rating variable and thereby select themselves in treatment and control groups

(Lee and Lemieux [2010]). For this purpose, we examine the frequency

distribution of firms around the thresholds and find no abnormal jumps.

These results suggest that our RDD analysis is not affected by the possibility that potential treatment firms might have managed their profits/book

value/sales to fall right below the cutoff to escape having to comply the

law. Further, our results are robust to both nonparametric and parametric

techniques of estimating the treatment effect.

We make several contributions to the literature. First, our paper establishes a potentially causal link between CSR and firm value. Establishing

causality between CSR and firm value is difficult due to potential confounding factors that may also contribute to a firm’s decision to engage in CSR.

To overcome this hurdle, we use an RDD around regulatory change which

forced certain firms to spend on CSR, as a mechanism to examine whether

CSR indeed affects shareholder value. This research setting significantly

mitigates endogeneity concerns and makes it more likely that changes in

firm value around the event can be attributed to CSR.

Second, we document a negative relation between mandatory CSR and

shareholder value. Our finding suggests that if firms choose their CSR

spending optimally before the law was imposed, there ought to be no relation between voluntary CSR and firm value. Forcing these firms to spend

1262

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

on CSR therefore has a negative impact on shareholder value. A related

implication of our paper is that studies that find an association between

corporate outcomes (e.g., higher operating performance, lower cost of capital, or lower earnings management) and voluntary CSR spending need to

grapple with the possibility that such associations are confounded by omitted variables, consistent with Himmelberg, Hubbard, and Palia [1999].

Third, a majority of prior studies consider voluntary CSR. To the best of

our knowledge, we are the first to examine the impact of legislatively mandated CSR spending. Our results demonstrate that forcing firms to spend

on CSR, on average, is likely to lead to negative consequences for shareholders. Finally, our study complements prior research that examines the

effect of firm-specific characteristics on the relationship between CSR and

shareholder value (e.g., Servaes and Tamayo [2013], Di Giuli and Kostovetsky [2014]). We show that firms with greater advertisement spending are

less likely to be negatively affected by the mandatory CSR rule.

Like any study that exploits a legislative change set in a particular institutional context, our paper also suffers from certain limitations relating

to generalizability. It can be argued that the mandatory CSR activities prescribed by the Indian Companies Act 2013 are different in nature from

the voluntary CSR seen in the rest of the world. Although the findings are

relevant for India, it is unclear whether these findings can be applied to

other parts of the world which have different economic and regulatory environments. We submit that, despite these generalizability limitations, the

key findings of our paper have implications for efforts to encourage CSR

in other economies. In particular, our study suggests that giving the firm

flexibility to define what CSR means and letting it choose where it wants to

direct its CSR spending is preferable from the shareholder’s perspective.

2. Related Literature and Hypotheses

Does CSR affect firm value? The existing theoretical literature on this

question can be categorized under two opposing views: (i) shareholder expense view; and (ii) stakeholder value maximization view. The shareholder

expense view follows Milton Friedman’s [1970] assertion that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Friedman argues that CSR

involves managers spending shareholders’ money and “in effect imposing

taxes, on one hand, and deciding how the tax proceeds shall be spent, on

the other.” He considers CSR to be a drain on the firm’s valuable resources

that should be utilized for shareholder value maximization.

In contrast to the shareholder expense view, Freeman’s [1984] stakeholder theory argues that a firm should consider the interests of everyone

who substantially affects (or is affected by) the welfare of the firm. Thus,

social, environmental or ethical preferences of stakeholders can induce

CSR activities (Baron [2001], McWilliams and Siegal [2001]). Such strategically motivated CSR activities can be profitable and the management

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

1263

literature terms this thesis as “doing well by doing good.” 7 Following this

stakeholder view, studies have documented that a high commitment to CSR

activities is associated with attracting and retaining higher quality employees (Greening and Turban [2000]), improving the effectiveness of the marketing of products and services (Fombrun [2005]), increasing demand for

products and services (Navarro [1988]), providing superior access to valuable resources (Cochran and Wood [1984]), generating moral capital or

goodwill that tempers punitive actions by regulatory agencies during a negative event (i.e., an insurance effect) and thereby preserving or increasing

firm value (Godfrey [2005]).

The economics-based reasoning for profitable CSR is that these activities

reduce transaction costs with stakeholders and provide net benefits to the

firm. The theory of the firm, as advanced by Coase [1937] and expanded by

Jensen and Meckling [1976], among others, views a firm as a nexus of contracts (both explicit and implicit) between shareholders and other stakeholders in which each group of stakeholders supplies the firm with critical

resources. Firms that undertake CSR activities tend to develop a reputation for keeping their commitments associated with the implicit contracts.

Consequently, stakeholders of these firms are more likely to contribute resources and effort to the firm and accept less favorable explicit contracts

(compared to stakeholders of firms with no or low levels of CSR activities).

The empirical evidence on the direct effect of CSR on firm value is

mixed. Margolis, Elfenbein, and Walsh [2009], in their influential metaanalysis of roughly 167 studies, find that some studies document a positive

effect when they regress firms’ financial performance (either accountingbased ROA or stock returns) on corporate goodness while others find a

negative effect. The average effect across these studies is a small positive

increase in firm performance. More recently, Dhaliwal, Li, Tsang, and Yang

[2011] conclude that the voluntary disclosure of CSR activities (i) attracts

institutional investors and analysts; and (ii) reduces the firm’s cost of capital. Servaes and Tamayo [2013] find that CSR activities and firm value are

positively related for firms with high customer awareness. In contrast, Di

Giuli and Kostovetsky [2014] find that Democrat-leaning firms are associated with more CSR activities than Republican-leaning firms, and increases

in firms’ CSR ratings are associated with negative future stock returns and

declines in ROA. This finding suggests that CSR activities that are motivated

by the political affiliation of stakeholders come at the expense of firm value.

While the discussion so far focuses on how voluntary CSR can be costly

or beneficial to shareholders, we have to also consider the implications

of mandatory CSR in India, as imposed by the Companies Act. There are

several reasons why mandatory CSR activities and their disclosure may not

benefit, and might even harm, shareholders. If Friedman’s view of CSR is

7 Benabou and Tirole [2010], Margolis, Elfenbein, and Walsh [2009], and Kitzmueller and

Shimshack [2012] are some papers that review the literature on “doing well by doing good.”

1264

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

indeed descriptively valid and firms optimally choose not to spend funds

on CSR, imposing binding legal constraints on their CSR choices will lead

to declines in their shareholder values. Once CSR spending and its reporting become mandatory, the Government could start prescribing how the

CSR money should be spent, thereby limiting a firm’s flexibility in coming

up with its CSR policies. Moreover, various interest groups may find it easier to lobby management to advance their environmental and social goals.

Finally, mandatory CSR also comes with compliance obligations such as administrative costs associated with reporting information and the need for

the board to monitor the firm’s CSR activities.

While a new regulation could often impose net costs on shareholders,

there can be circumstances where the regulation could be beneficial.8 In

the pre-mandatory CSR period, managers potentially expend a sub-optimal

level of CSR because of pressures to achieve short-term earnings targets.

However, under mandatory CSR, managers may be nudged to cultivate relations with various stakeholders that might pay off in the long run. Moreover, managers’ CSR activities could reflect their own social preferences. Increased reporting and governance requirements imposed by the law might

make firms redirect their CSR spending to maximize firm value. Finally, as

discussed earlier, firms could use CSR activities to signal their commitment

toward their implicit contracts. Mandatory CSR requires a firm to make its

CSR policies more formalized and visible, which, in turn, could strengthen

such a commitment. Hence, the terms of the firms’ explicit contracts could

become more favorable to the firm.

In summary, there are several ways in which CSR can either have a positive or negative impact on firm value. Based on this discussion our first

hypothesis is:

H1: The mandatory CSR rule affects shareholder value.

We go on to hypothesize conditions under which mandatory CSR rule is

likely to affect firm value differentially. Motivated by prior work on CSR, we

consider whether the impact of CSR on shareholder value varies depending on the firm’s political connections, its advertisement spending, and its

affiliation to a highly polluting industry.

First, we consider the impact of a firm’s political connectedness on the

relation between CSR and firm value. Faccio [2006] suggests that political connections can be of value to a firm in several ways including preferential treatment by government-owned enterprises (such as banks or raw

material producers), lower taxation, preferential treatment in competition

for government contracts, relaxed regulatory oversight of the company in

8 For example, Chhaochharia and Grinstein [2007] find that certain governance-related

provisions of Sarbanes Oxley Act led to increase in firm value. Black and Khanna [2007] find

that the governance reforms (Clause 49) introduced in India are associated with positive stock

market reaction. Similarly, Black and Kim [2012] find that the 1999 Korean governance reforms also led to increase in firm value for the affected firms.

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

1265

question, or stiffer regulatory oversight of its rivals. However, as pointed by

Shleifer and Vishny [1994], politicians themselves will extract at least some

of the rents generated by connections, and firm value will be enhanced only

when the marginal benefits of the connections outweigh their marginal

costs. CSR spending might constitute a potential mechanism via which a

firm can satisfy the preferences of politicians and increase its ability to conduct business with the government and other entities with their political

connections.

Political connections assume greater importance in the context of India where government regulation is high, corruption is accepted as a

ground reality, and enforcement mechanisms are unpredictable (Khanna

and Palepu [2000]). Consequently, CSR activities can become an important

part of corporate strategy to enhance these political ties. For example, in his

inaugural Independence Day speech, the Prime Minister of India recently

urged corporations to take up building toilets in schools as a priority under

their CSR policies. Within four days, companies announced over INR 200

crore (US$ 33.33 million) of contributions to the government’s “Swachh

Bharat” (Clean India) campaign.9 To the extent firms can use CSR as a

mechanism to enhance their political ties, CSR can be valuable. Therefore,

we hypothesize that:

H2a: The negative (positive) effect of mandatory CSR rule on shareholder

value is lower (higher) among firms that are politically connected.

The marketing and management literature suggest that CSR activities

of a firm can attract customers. Fisman, Heal, and Nair [2008], in their

model, argue that consumers realize that only firms that care about product

quality are willing to invest in CSR activities because purely profit-oriented

firms (that can compromise on quality) find these investments to be “too

expensive.” By engaging in CSR, firms are able to identify themselves as

the ones selling better quality products. Further, socially responsible consumers (e.g., “green” consumers) are more likely to buy and some are even

willing to pay more for products of CSR firms (Navarro [1998], Sen and

Bhattacharya [2001]). Servaes and Tamayo [2013] find that CSR and firm

value are positively related for firms with high consumer awareness, as proxied by advertising expenditure. They argue that a necessary condition for

CSR to modify consumer behavior and hence affect firm value is consumer

awareness of the firm’s CSR activities. Advertising expenditure increases the

potential customers’ awareness of the firm, its products, and practices (including its CSR activities). This, in turn, is likely to increase the chances of

a consumer identifying with the product, thereby enhancing revenue and

eventually firm value. Following this logic, we hypothesize that:

9 http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Modis-Swachh-Bharat-call-gets-Rs-200-crorefrom-TCS-Bharti/articleshow/40384230.cms

1266

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

H2b: The negative (positive) effect of mandatory CSR rule on shareholder

value is lower (higher) among firms with high levels of advertisement

expenditure.

Finally, we investigate whether the negative effect associated with the

mandatory CSR rule is relatively strong among firms in polluting industries. Once CSR becomes mandatory, environmental activist groups and local communities can pressure these firms to spend money on green technologies or environmental controls. While these investments can benefit

the overall environment, they typically tend to yield limited firm-specific

benefits. Hence, we hypothesize that:

H2c: The negative (positive) effect of mandatory CSR rule on shareholder

value is higher (lower) among firms that are in high polluting industries.

3. Research Design and Data

3.1

BACKGROUND OF THE COMPANIES ACT

2013

The Indian Companies Act, 2013 was enacted on August 29, 2013. This

legislation attempts to overhaul a nearly 60-year-old Indian corporate law

framework to bring it in line with global best practices. A unique feature

of this Act is clause 135 (referred to as the CSR rule in this paper) which

specifies that if in any given year, a firm has either (1) a net worth of Indian

Rupees (INR) 5,000 million (about U.S. $83 million) or more; (2) sales of

INR 10,000 million (about U.S. $167 million) or more; or (3) a net profit

of INR 50 million (about U.S. $0.83 million), it is required to spend 2% of

its average net profits of the last three years on CSR activities.

For example, the rule implies that if in the year 2012, a firm that meets

any of the three criteria has to spend 2% of profits averaged over the three

years, 2010, 2011, and 2012. Similar to Iliev [2010], in the context of section 404 of the Sarbanes Oxley Act, these numerical thresholds help us

disentangle the contribution of the CSR rule from other requirements of

the Companies Act 2013 (e.g., enhanced corporate governance and disclosure norms, greater accountability of management and auditors; stricter

enforcement, protection for minority shareholders, etc.) that apply to all

listed firms, regardless of numerical cutoffs.

The passage of Companies Act 2013 is a culmination of several years of

effort. We focus on eight event dates that represent major milestones in the

legislative passage of the Act. Figure 1 summarizes the timeline of events.

These events are as follows:

r Event # 1: The Companies Act was first introduced in the Lok Sabha

(the lower house of the Indian parliament) on August 3, 2009 as the

Companies Bill, 2009 (Bill, hereafter). The Bill in its original form had

no clause on CSR.

r Event # 2: The 2009 version of the Bill was referred to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance, which submitted its report on

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

Event # 1

Aug 3, 2009

Event # 2

Aug 31, 2010

Event # 3

Feb 28, 2011

Event # 4

Dec 14, 2011

Introduction

of the

Company’s

Bill 2009 in

the Lok

Sabha

For the first

time,

Standing

Committee

on Finance

inserts the

notion of

Mandatory

CSR in its

report

Bowing to

corporate

pressure, the

Ministry of

Corporate

Affairs

announces

that it is

considering

making CSR

voluntary

and not

mandatory

Government

eventually

goes ahead

with the

mandatory

CSR and

introduces a

revised

Company’s

Bill in the

Lok Sabha

Event # 5

Jun 26, 2012

Standing

Committee

on Finance

endorses the

bill with no

new changes

relating to

mandatory

CSR

1267

Event # 6

Dec 18, 2012

Event # 7

Aug 8, 2013

Event # 1

Aug 29, 2013

The

Companies

Bill 2012,

containing

mandatory

CSR clause,

is passed in

the Lok

Sabha

The

Companies

Bill 2012 is

passed in

the Rajya

Sabha

The

President

signs the

bill and it

is enacted

FIG. 1.—Timeline of important events related to the passage of the mandatory CSR rule.

August 31, 2010. The Finance Committee introduced the notion of

mandatory CSR for the first time in its report dated August 31, 2010.

Anecdotal evidence and reports in the popular press suggest that the

Finance Committee, perhaps anticipating popular backlash that might

result from a very progressive pro-business bill, inserted several new

clauses to make the bill slightly more pro-development. The proposal

mandating CSR spending was among these clauses and noted that:

“every company having [(net worth of rupees 500 crore or more, or

turnover of rupees 1000 crore or more)] or [a net profit of rupees 5 crore

or more during a year] shall be required to formulate a CSR Policy to ensure

that every year at least 2% of its average net profits during the three immediately preceding financial years shall be spent on CSR activities as may

be approved and specified by the company.”10

r Event # 3: On account of protests from industry, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs announced on February 28, 2011 that it is considering

making only the disclosure, as opposed to the actual spending, of CSR

mandatory. The proposal for mandatory CSR attracted a lot of criticism from companies who argued that what they spend on community

welfare, education, health, development, and environmental activism

is for them to decide. Azim Premji, Chairman of Wipro Ltd., opposed

mandatory CSR and argued that “my worry is the stipulation should

not become a tax at a later stage ... Spending two per cent on CSR is a

lot, especially for companies that are trying to scale up in these difficult

times. It must not be imposed.” He also felt that a distinction should

be made between personal philanthropy and CSR, which is a company

activity.11 Murli Deora, the Minister of Corporate Affairs (the ministry

10 From a research design standpoint, as discussed later, it is important to note that these

numerical cutoffs introduced on August 31, 2010, remained unchanged through various iterations of the bill until the bill became law.

11 http://businesstoday.intoday.in/story/azim-premji-aima-convention-corporate-socialresponsibility/1/198960.html

1268

r

r

r

r

r

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

that crafted the Companies Bill, 2009), also acknowledged that there

was an argument as to whether the Government should mandate anything.

Event # 4: The Ministry of Corporate Affairs eventually resisted pressure from corporate houses and went ahead with the mandatory CSR

rule.12 Keeping in view the recommendations made by the Finance

Committee, a revised Bill was prepared and the original Bill was withdrawn. The new Bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha on December 14,

2011. The Bill was again referred to the Finance Committee as certain

new provisions, which had not been referred earlier to the committee,

were included in this new Bill.

Event # 5: The Finance Committee submitted its report on June 26,

2012.

Event # 6: The Lok Sabha subsequently approved the Bill on December

18, 2012 and labeled it as the Companies Bill, 2012.

Event # 7: The Companies Bill, 2012 was then considered and approved by the Rajya Sabha (the upper house of the Indian parliament)

on August 8, 2013 as The Companies Bill, 2013.

Event # 8: The Companies Bill, 2013 received the President’s assent on

August 29, 2013 and has now become law.

Under the hypothesis that CSR is value-destroying, we expect firms affected by the mandatory CSR rule to experience (i) negative stock market

reactions on Event # 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 because each of these events is associated with an increased probability that the mandatory CSR rule will pass;

and (ii) a positive stock market reaction on Event # 3 because it mitigates

any possible harmful effects of the mandatory CSR rule by decreasing the

probability that the legislation, in its proposed form, will pass.

While the term “CSR” itself is not defined in the Act, Schedule VII of the

Companies Act, quoted below, requires CSR activities of the firm to focus

on at least one of the following areas: (i) eradicating extreme hunger and

poverty; (ii) promotion of education; (iii) promoting gender equality and

empowering women; (iv) reducing child mortality and improving maternal

health; (v) combating HIV, AIDS, malaria and other diseases; (vi) ensuring

environmental sustainability; (vii) employment-enhancing vocational skills;

(viii) social business projects; (ix) contribution to the Prime Minister’s National Relief Fund or any other fund set up by the Central Government

or the state governments for socioeconomic development, and relief and

funds for the welfare of the scheduled castes, the scheduled tribes, other

backward classes, minorities and women; and (x) such other matters as may

be prescribed.13

12 Such resistance also suggests that reverse causality (from firm value to the implementation of the law) is highly unlikely.

13 Descriptive data on the magnitude and nature of CSR spending for one year, 2012, are

presented in panels B and C of table 1.

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

1269

The CSR rule also provides guidance on the enforcement mechanism

needed to achieve the CSR goals. Specifically, it requires that a firm create a CSR committee consisting of three or more directors, at least one of

which must be an independent director. The CSR committee is expected

to devise, recommend, and monitor CSR activities, and the amounts spent

on such activities. The new rule also requires that a firm must (i) publicly

disclose an official policy on its CSR activities and document CSR activities

implemented during the year in its annual report; and (ii) demonstrate a

preference for local areas where they operate. While a company is not subject to liability for failing to spend on CSR, a company and its officers are

subject to liability for not explaining such a failure in the annual report of

the board of directors.14

Overall, the mandatory CSR rule of the Companies Act, 2013 is a unique

regulation as it may be the first time in the world that a country has mandated expenditures for the public good, rather than simply tax companies

or leave them to conduct CSR activities on their own. According to Ernst &

Young, these provisions would generate over U.S. $2.5 billion of CSR spending annually. India is home to the largest concentration of poverty on the

planet and can certainly benefit from this large inflow of funds to socially

responsible activities. However, it is unclear whether such mandatory CSR

improves or hurts shareholder value.

3.2

EVENT STUDY APPROACH AND ASSUMPTIONS

To capture the effect of the CSR rule on firm value, we compare the

CAR of AFFECTED firms to those of UNAFFECTED firms (controlling for

other firm attributes that are likely to affect returns) around each of the

eight key legislative events related with the passage of the Companies Act

2013, as outlined in section 3.1. On each event date, we classify a firm as

AFFECTED or UNAFFECTED based on whether its profit/sales/book value

for the most recent fiscal year end meets the thresholds mentioned in the

CSR rule or not. For example, a firm whose profit equals INR 50 million

for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2010 would be classified as AFFECTED

when we consider the event date August 31, 2010. We measure abnormal

returns by estimating the market model using 200 trading days of return

data ending 11 days before the legislative event. The return on CNX 500

index is used as a proxy for market return.15 Daily abnormal stock returns

are cumulated to obtain the CAR from day t−1 before the legislative event

date to day t + 1 after the event date.

14 Failure to explain is punishable by a fine on the company of not less than INR 50,000

(about U.S. $833) and up to INR 25 lakhs (about U.S. $41,667). Further, officers who default

on the reporting provision could be subject to up to three years in prison and/or fines of not

less than INR 50,000 rupees (about U.S. $833) and as high as INR 5 lakh (about U.S. $8,333).

15 CNX 500 is a broad-based benchmark of the Indian capital market. It comprises

of 500 firms that represents about 96% of the free float market capitalization of the

stocks listed on National Stock Exchange of India (NSE). More details can be found at

http://www.nseindia.com/products/content/equities/indices/cnx 500.htm

1270

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

Before we proceed any further with the discussion of market reaction

tests, we lay out certain crucial assumptions that we need to make to interpret these results. It is important to emphasize that we do not assume that

the stock market has perfect foresight. Specifically, on any given event date,

the stock market does not know (i) if and when the CSR law will eventually

go in effect, and (ii) what the final form of the CSR law will look like when

it is eventually passed. Hence, the events we examine represent the natural

progression of a bill under the Indian parliamentary system. It is reasonable to assume that as we proceed along the time line of event dates (i) the

probability of eventual passage of the law increases, and (ii) the probability

of changes to the current version of the bill decreases. Therefore, the difference in the market reaction for the AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED firms

on any event date captures the market’s assessment of the eventual passage

of the law in its current form. We use such market reaction to proxy for the

effect of CSR activity on firm value.

It is important to note that our classification of firms into AFFECTED

and UNAFFECTED does not induce any perfect foresight bias. As mentioned earlier, we classify a firm as AFFECTED or UNAFFECTED based on

whether its profit/sales/book value for the most recent fiscal year end

meets the thresholds mentioned in the CSR rule or not. However, it is

not known whether that same company would continue to meet the profitability threshold at some point of time in future when the CSR rule is

actually passed and is effective. We assume that the market considers the

current level of profitability as an indicator of future profitability. Thus,

we assume that firms that are classified as AFFECTED on a given event

date before the passage of the law are also more likely to be classified as

AFFECTED even after the passage of the law. This assumption is further

strengthened by the fact that three firm characteristics (profitability, sales,

and book value) are used to classify a firm as AFFECTED or UNAFFECTED.

Because the numerical cutoffs related to these three firm characteristics

represent either or conditions, it is unlikely that a firm classified as AFFECTED on a given event date will not be classified as AFFECTED in the

future.16

16 These assumptions are reasonable because (i) the Companies Act with a CSR clause in it,

even though introduced in 2010, eventually was passed in 2013; (ii) no changes were made in

the threshold profit/sales/book value levels that would go in determining whether a firm will

be affected by the CSR rule or not; and (iii) on average, about 83% of firms that we classify

as AFFECTED in year t remain classified as AFFECTED in year t + 1. Similarly, 62% of firms

that we classify as UNAFFECTED in year t remain classified as UNAFFECTED in year t + 1. In

fact, with the benefit of hindsight, it can also be argued that the market fails to anticipate the

time needed to shepherd the Indian Companies Act 2013 into law. For example, by reacting

to Event 2 (figure 2b) as it did, the market is effectively acting as if the legislation will go into

effect immediately. As it turns out, the legislation took another three years, by which time,

whether a firm fell on one side of the cutoff in figure 2b is largely uncorrelated with whether

the firm fell into the AFFECTED category in 2013.

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

3.3

1271

BASIC SET UP OF A REGRESSION DISCONTINUITY DESIGN

We combine the event study approach with a regression discontinuity design (RDD) to document the effect of CSR rule on firm value. The RDD

technique was first introduced by Thistlethwaite and Campbell [1960] in

a study that examined the impact of merit awards on future academic outcomes of students. In their setting, students with test scores, R, greater than

or equal to a cutoff value c received an award, and those with scores below

the cutoff did not receive an award. The process of granting merit awards

generates a sharp discontinuity in the treatment variable (which is receiving the award, in this case) as a function of the rating variable (which is test

score, in this case).17 More formally, the receipt of treatment is denoted by

the dummy variable D ∈ {0, 1}, where D = 1 if R ࣙ c, and D = 0 if R < c. This

framework assumes that individuals with scores just below the cutoff (who

did not receive the award) are very much comparable to individuals with

scores just above the cutoff (who did receive the award). Therefore, a discontinuous jump in Y at c can be attributed to the causal effect of the merit

award because there is likely to be no reason, other than the merit award,

for future academic outcomes, Y, to be a discontinuous function of the test

score. The relationship between Y and R can therefore be estimated using

the following regression model:

Y = α + τ D + f (R) + ε,

(1)

where the term τ captures the effect of merit awards on future academic

outcomes. The inferences drawn under an RDD approach are considered

to be credible because the assignment of individuals in treatment and control groups is “as good as randomized” given that individuals cannot precisely control the assignment variable near the exogenously determined

cutoff (Lee and Lemieux [2010]).

Since the 1990s, the RDD technique has been used in a variety of economic contexts. Some recent applications of RDD in finance include: (i)

Akey [2015] who estimates the value of a firm’s political connections by

comparing the differences in abnormal stock returns of firms connected

to candidates who just won/lost a close election; (ii) Flammer [2015] who

estimates the effect of CSR on firm value by comparing the stock market

reaction to firms whose CSR proposals pass/fail by a small margin of votes;

(iii) Black and Kim [2006] who study Korean governance reforms, which

apply to firms with assets greater than 2 trillion Korean Won, but not to

smaller firms; and (iv) Iliev [2010] who studies the impact of section 404 of

Sarbanes-Oxley, which applies to U.S. firms with $75M public float but not

to the smaller firms.

Our setting of the mandatory CSR rule nicely fits the RDD framework.

The mandatory CSR rule imposes certain profitability/size cutoffs that

17 The rating variable is also referred to as forcing variable or the assignment variable in the

literature.

1272

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

classify firms as AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED. Assuming firms that are just

above and below the cutoffs are fundamentally similar, unobservable firm

characteristics are less likely to impact the relation between CSR and firm

value. Further, there is no reason to believe that one group is more likely

to undertake CSR activities than the other, thereby mitigating the concern that firms spending on CSR self-select themselves based on their private information about future profitability, as suggested by Lys, Naughton,

and Wang [2015]. Therefore, any differences in the stock market reaction around key events related to the passage of mandatory CSR rule, as

measured by CAR, for the two groups of firms (i.e., AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED) can thus be attributed to the mandatory CSR rule that creates the

discontinuity.

Our research setting differs from the basic RDD applications listed above,

in that the mandatory CSR rule relies on more than one rating score to

determine treatment status. A firm is affected by the mandatory CSR rule

if during any fiscal year it has either (i) a net worth of Indian Rupees

(INR) 5,000 million (about U.S. $83 million) or more; (ii) sales of INR

10,000 million (about U.S. $167 million) or more; or (iii) a net profit of

INR 50 million (about U.S. $0.83 million) or more. Researchers label this

special case of the RDD as multivariate RDD or MRDD. While there are

several methods to estimate treatment effects under MRDD, we follow a

binding-score regression discontinuity as described in Reardon and Robinson

[2012].18 Specifically, we create a new rating variable M, defined as the

minimum of the three individual rating scores based on profits, book value,

and sales (where each score is first centered around its cutoff score), that

perfectly determines the assignment. Continuing with the notation used in

model (1), receipt of treatment is denoted by the dummy variable D {0, 1},

where D = 1 if M ࣙ c, and D = 0 if M < c. We then fit the following model:

Y = α + τ D + f (M ) + ε.

(2)

As pointed out by Reardon and Robinson [2012], the binding-score regression discontinuity model is appealing because it is intuitively simple

and it parsimoniously reframes the multidimensional vector of rating scores

into a single dimension that alone determines treatment status, and hence

ensures minimal loss of data in estimation.

3.4

DATA

The data for our study are obtained primarily from Prowess, a database

maintained by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). The

Prowess database is widely used by scholars (e.g., Khanna and Palepu

[2000], Bertrand, Mehta, and Mullainathan [2002], Gopalan, Nanda, and

Seru [2007]) to conduct large sample studies on Indian firms.

18 Other methods to implement MRDD include response surface RD, frontier RD, fuzzy

frontier RD, and distance-based RD. Please refer to Reardon and Robinson [2012] and Wong,

Steiner, and Cook [2013] for more details.

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

1273

Our full sample comprises of firms with nonmissing data on total assets,

sales, net income, book value of equity, and market capitalization. We also

require a firm to have stock return data around key event dates related to

the passage of the Companies Act. These data restrictions yield a sample

of 9,921 firm-year observations relating to 2,120 unique firms for the period 2009–2013. There are 5,889 firm year observations (59% of the sample) that are classified as AFFECTED and the remaining 4,032 firm-year

observations (41% of sample) are classified as UNAFFECTED. Panel A of

table 1 presents the industry-wise distribution of our sample. Business services, chemicals, construction, textile, and wholesale industries are heavily

represented among the AFFECTED firms.

To assess whether the nature of CSR spending voluntarily incurred by

firms is consistent with the nature of CSR activities enumerated by the law,

we hand-collect information on the magnitude and characteristics of CSR

spending for just one year from the 2012 annual report or CSR reports of

firms. In panels B and C of table 1, we describe amounts spent on CSR and

the type of activities undertaken.19 Of the 1,237 AFFECTED firms for the

year 2012, only 458 firms (37%) spend money on CSR activities. Panel B

presents the descriptive statistics on the amount of CSR spent by the AFFECTED firms in the year 2012. The median amount spent on CSR is INR

3.02 million (approx. $50,333) which is roughly 0.37% of the average of last

three years’ net income. The 75th percentile for CSR spending as a proportion of net income is 1.31%. Hence, before the passage of the CSR law, a

majority of firms do not spend funds on CSR and those that do, spend well

below the proposed 2% level. Panel C provides details on the type of CSR

activity undertaken by these firms. The most common areas where firms

focus their CSR spending are related to community welfare, education, environment, and health care. These areas of spending are mostly in line with

the type of CSR activities listed in the mandatory CSR rule.

To implement RDD, we focus on firms that are just below and just above

the cutoff prescribed in the CSR rule. Specifically, we select firms whose

binding score rating variable M (as defined in section 3.3) ranges between

–0.50 and +0.50. Hereafter, we refer to this subsample as the RDD sample.

The RDD sample comprises of 2,664 firm year observations from 2009 to

2013. Of these total observations 1,633 firm year observations (61% of the

RDD sample) are classified as AFFECTED and the remaining 1,031 firm-year

observations (39% of RDD sample) are classified as UNAFFECTED. Because

the RDD analysis is conducted separately for each event date, and each

year can have multiple events, the exact number of observations used in

each test is different.

19 To be clear, we intend for the 2012 data on CSR magnitude and type of spending in panels

B and C to be a completely descriptive analysis. We emphasize that we do not use these CSR

magnitude data from 2012 to classify firms as treated and control firms throughout the paper.

In particular, we do not use the 2012 magnitude of CSR spending in any of the regression

analyses reported in the paper.

1274

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

TABLE 1

Sample Description

Panel A: Industry-wise distribution

Industry

UNAFFECTED

AFFECTED

TOTAL

%

135

167

380

263

161

69

87

89

134

121

98

207

133

294

348

462

884

4,032

41%

337

306

415

491

475

177

153

166

236

276

154

295

322

328

205

214

1,339

5,889

59%

472

473

795

754

636

246

240

255

370

397

252

502

455

622

553

676

2,223

9,921

5%

5%

8%

8%

6%

2%

2%

3%

4%

4%

3%

5%

5%

6%

6%

7%

22%

100%

Automobiles and Truck

Banking

Business Services

Chemicals

Construction

Construction Material

Consumer Goods

Electrical Equipment

Food Products

Machinery

Nonmetallic and Industries

Pharmaceutical Production

Steel Works etc.

Textiles

Trading

Wholesale

Other industries with < 2% frequency

Total

Panel B: Descriptive data on CSR spending

N = 458

Mean

Median

SD

P25

P75

CSR spending (INR million)

CSR spending /average last three years profits (%)

49.30

1.22

3.02

0.37

200.89

2.31

0.53

0.07

14.39

1.27

Panel C: Descriptive data on CSR activity undertaken

CSR activity

Community welfare

Education

Environment

Healthcare

Rural development

Women empowerment

Children health

Donations

Disaster relief

Sports

Support for physically challenged

N

%

242

212

191

178

44

37

35

31

25

12

9

52.84%

46.29%

41.70%

38.86%

9.61%

8.08%

7.64%

6.77%

5.46%

2.62%

1.97%

Our full sample consists of 9,221 firm year observations over the period 2009–2013. In panel A of this

table, we present the industry-wise distribution of the sample. In panels B and C of this table, we provide

descriptive statistics on amount spent on CSR, and the type of CSR activity undertaken by sample firms

in the year 2012. Note that the data in panels B and C are descriptive in nature and are not used in any

regression analysis reported in the paper.

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

1275

4. Results

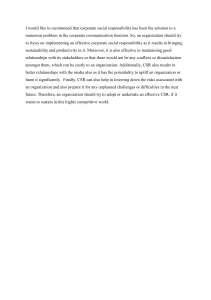

4.1 VERIFYING ASSUMPTIONS UNDERLYING RDD

Consistent with the best practices recommended by Lee and Lemieux

[2008], we begin by testing two crucial assumptions of RDD. The first assumption is that individuals cannot precisely manipulate the rating variable

and hence cannot select themselves into the treatment and control groups.

For example, if firms systematically manage earnings downwards to report

earnings below INR 50 million to avoid compliance with the mandatory

CSR rule, then inferences based on RDD would be invalid because the assignment of firms in the treatment and control groups is not as good as

randomized. To examine this possibility, we graph the frequency of firms

around the profits, book value, and sales cutoffs prescribed in the CSR rule

for the year 2009 and the year 2013. In the year 2009, there was no information about the mandatory CSR rule, whereas in the year 2013, the guidelines for mandatory CSR were well known. Any abnormal jump (drop)

in the frequency of firms just to the left (right) of the cutoff in the year

2013, relative to the year 2009, would suggest that firms deliberately manipulated their profits/book value of equity/sales to avoid potential compliance with the mandatory CSR rule. Figures 2a–2f show no such jumps

or drops in the frequency of firms. Further, in our setting, three different

cutoffs determine the assignment into the treatment group. Hence, the

likelihood that a firm will simultaneously manipulate all the three different

thresholds to avoid compliance with the mandatory CSR rules is relatively

low.

Another important aspect of RDD is that for this approach to work, all

other factors that determine the dependent variable (CAR in our case)

must also evolve smoothly with respect to the rating variable. If the other

variables also show a discontinuity at the cutoff, then the estimated treatment effect of the intervention will be biased. In order to test the validity

of this assumption, we compare the mean and median values of the various

characteristics of AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED firms of the RDD sample.

These results are documented in table 2. The construction of these variables is explained in appendix A. AFFECTED firms are typically larger and

more profitable than the UNAFFECTED firms. This is to be expected because the cutoffs that divide firms as AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED firms

are based on size and profitability. However, AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED

firms are similar in terms of other firm characteristics that are likely to affect firm value such as leverage, sales growth, cash holdings, and board

independence.

AFFECTED firms are more likely to belong to a business group compared to UNAFFECTED firms. We adopt the Prowess database’s group classification to identify business group affiliation and government ownership.

Although we do not have an explicit hypothesis related to group affiliation,

that variable is important to control for in the Indian context, as done previously by Khanna and Palepu [2000], Bertrand, Mehta, and Mullainathan

1276

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

(a)

(b)

Distribution of firms around INR 500 million profit cutoff on 08/29/2013

0

0

50

50

Frequency

Frequency

100

100

150

150

Distribution of firms around INR 500 million profit cutoff on 08/03/2009

-50

0

50

Profit

100

150

-50

0

50

Profit

(c)

100

150

(d)

60

Distribution of firms around INR 5,000 million book value cutoff on 08/29/2013

0

0

20

20

Frequency

Frequency

40

40

60

Distribution of firms around INR 5,000 million book value cutoff on 08/03/2009

2000

3000

4000

5000

Book value

6000

7000

8000

2000

3000

4000

(e)

5000

Book value

6000

7000

8000

(f)

40

Distribution of firms around INR 10,000 million sales cutoff on 08/29/2013

0

0

10

10

Frequency

20

Frequency

20

30

30

40

Distribution of firms around INR 10,000 million sales cutoff on 08/03/2009

5000

7500

10000

Sales

12500

15000

5000

7500

10000

Sales

12500

15000

FIG. 2.—Did firms manipulate profits, book value, or sales to avoid mandatory CSR compliance? Graphs 2a and 2b (2c and 2d) plot the frequency distribution of firms around the

INR50 million profit cutoff (INR5,000 million book value cutoff). Graphs 2e and 2f plot the

frequency distribution of firms around the INR10,000 million sales cutoff. Firms with profit,

book value, or sales above these cutoffs are required by law to spend funds on CSR. Graphs

to the left (a, c, and e) are based on values on 08/03/2009, when the information about

mandatory CSR rule was unknown. Graphs to the right (b, d, and f) are based on values on

08/29/2013 when the information about the mandatory CSR rule was fully known.

[2002], Gopalan, Nanda, and Seru [2007], and other papers. AFFECTED

firms spend more on advertising than UNAFFECTED firms. Further, AFFECTED firms are more politically connected than UNAFFECTED firms. We

measure political connectedness using a dummy variable POLITICAL that

equals one if the firm or the business group to which a firm belongs has

made a contribution of INR 20,000 or more to a political party in India between 2005 and 2012, and zero otherwise. We obtain these data from the

Median

1.4889

0.0236

1.8766

0.5074

0.0203

0.0039

0.0259

0.4615

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

Mean

3.0191

0.0245

2.4263

0.4828

0.0505

0.0805

0.0574

0.4709

0.1009

0.1649

0.0010

0.0126

0.0016

0.0155

0.4578

SD

4.3100

0.0635

1.7854

0.2281

0.0761

0.2487

0.0882

0.1177

0.3013

0.3713

0.0311

0.1116

0.0076

0.1237

0.4985

12.3165

0.0492

1.9229

0.4887

0.0569

0.0780

0.0653

0.4611

0.2394

0.3356

0.0031

0.0276

0.0043

0.0790

0.4770

Mean

8.6899

0.0413

1.4392

0.5089

0.0315

0.0026

0.0351

0.4545

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

Median

SD

15.9263

0.0611

1.5815

0.2162

0.0714

0.1919

0.0848

0.1162

0.4269

0.4723

0.0553

0.1637

0.0132

0.2698

0.4996

AFFECTED (2) N = 1,633

[3] – [2]

7.2010∗∗∗

0.0177∗∗∗

−0.4374∗∗∗

0.0015

0.0113∗∗

−0.0013

0.0092

−0.0070

0.0000∗∗∗

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000∗∗∗

0.0000∗∗∗

0.0000

9.2973∗∗∗

0.0247∗∗∗

−0.5034∗∗∗

0.0059

0.0064∗∗

−0.0025

0.0079

−0.0098

0.1386∗∗∗

0.1707∗∗∗

0.0021

0.0149

0.0026∗∗∗

0.0635∗∗∗

0.0192

Difference in median

[2] – [1]

Difference in mean

This table reports the mean, median, and standard deviation of various firm characteristics for the AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED firms for the RDD sample, which comprises of

2,664 firm year observations from 2009 to 2013. The RDD sample is constructed as follows. First, a binding score rating variable M is created which is defined as the minimum of the

three individual rating scores R1, R2, and R3, which are in turn defined as (Profit – 50)/50, (Book value – 5,000)/5,000, and (sales – 10,000)/10,000, and which perfectly determines

whether a firm is affected by the mandatory CSR rule or not. Profit, book-value and sales for the most recent fiscal year end before any event date are considered to eliminate any

perfect foresight bias. The INR 50 million profits, INR 5,000 million book value, and INR 10,000 sales are the three cutoffs specified in the mandatory CSR rule. If a firm has profit,

book value, or sale above these cutoffs, the firm is then required to spend on CSR. Firms with the variable M ranging between −0.50 and 0.50 comprise our RDD sample, where firms

with M > 0 are AFFECTED by the rule and firms with M < 0 are UNAFFECTED by the rule. The significance of differences in means and medians are evaluated based on the t-test and

Wilcoxon test, respectively (p-values for the t-statistics and Z-statistics are two-tailed). ∗∗∗ , ∗∗ and ∗ denote significance at 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

ASSETS (INR, billions)

ROA

BM

LEV

CAPEX

SGROWTH

CASH

BOARD INDPENDENCE

BIG4

BG

GOVT OWNED

MNC

AD

POLITICAL

POLLUTED

UNAFFECTED (1) N = 1,031

TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics for the RDD Sample

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

1277

1278

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

Web site of the Association of Democratic Reforms, a not-for-profit organization working in the area of electoral and political reforms in India.20

Finally, AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED firms have equal representation in

industries identified by Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government

of India as heavily polluting industries.21 The dummy variable POLLUTED

captures these industries and is equal to one if a firm belongs to metallurgical, chemical, petrochemical, coal, thermal power, building materials,

paper, brewing, pharmaceutical, fermentation, textiles, leather, or the mining industry, and zero otherwise. For these four variables we find no jumps

in the covariates at the cutoffs.22 These results give us comfort to proceed

with the RDD estimation.

4.2

UNIVARIATE RESULTS

In table 3, we report median CAR for the AFFECTED and the UNAFFECTED firms in the RDD subsample, around the each of the eight key

legislative events related to the passage of the Companies Act 2013, as outlined in section 3.1.

There is no significant market reaction to Event # 1 on August 3, 2009,

that is, when the Bill was introduced for the first time in the Lok Sabha

(lower house of the Indian Parliament). This outcome is not surprising

because the August 3, 2009 version of the Bill contained no clause related to

CSR. The insignificant result (which is akin to a placebo test) mitigates the

possibility that some unobserved firm characteristics drive the differences

in CAR for the two sub-samples. 23

On August 31, 2010 (Event # 2), the Standing Committee on Finance

presented its report with a mandatory CSR clause. We find a significant

negative market reaction for the AFFECTED (−2.3%) firms but a slightly

positive reaction for the UNAFFECTED firms (0.3%), consistent with the hypothesis that CSR is value-destroying. This event is important in the context

of our study because it contained news related to only the CSR aspect of

the Companies Act. As discussed in section 2, the Parliamentary Standing

Committee on Finance vetted the initial version of the Companies Act and

inserted a mandatory CSR clause. This new rule was a totally unexpected

addition to the Act. For the first time profitability/size/net-worth cutoffs

were prescribed to determine which firms will be affected by the mandatory CSR rule. These cutoffs eventually remained unchanged in the final

version of the bill that was enacted.

20 http://adrindia.org/research-and-report/political-party-watch/combined-reports/2014

/corporates-made-87-total-donations-k

21 http://envfor.nic.in/legis/ucp/ucpsch8.html

22 These results and accompanying graphs are available upon request.

23 Note that we have used the numerical cutoffs prescribed in the second event date

(August 31, 2010) to classify firms into AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED for stock returns related

to the first event date (August 3, 2009). In one sense, this reflects hindsight bias. We prefer

to interpret the null result related to returns on the first event date on August 3, 2009 as a

placebo test.

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

1279

TABLE 3

Market Reaction – Univariate Results Based on RDD Sample

Event

#

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Date

Aug 3, 2009

Aug 31, 2010

Feb 28, 2011

Dec 14, 2011

Jun 26, 2012

Dec 18, 2012

Aug 8, 2013

Aug 29, 2013

Median CAR for

a firm around

all eight events

Predicted sign on

AFFECTED firms (under

the hypothesis that CSR UNAFFECTED

is value-destroying)

(1)

Insignificant

−

+

−

−

−

−

−

−

0.003

0.003∗∗∗

−0.002

−0.001

0.002∗∗∗

0.006∗∗∗

−0.005∗∗

−0.004

−0.003

AFFECTED Difference

(2)

(2) – (1)

0.001

−0.023∗∗∗

0.004

−0.001

0.001∗

−0.016∗∗∗

−0.006

−0.003

−0.008∗

−0.001

−0.026∗∗∗

0.006

0.000

−0.001

−0.021∗∗∗

−0.001

0.001

−0.005

This table reports median 3-day CAR around the key legislative events for the two subgroups of our

sample, that is, UNAFFECTED, and AFFECTED firms in the RDD sample. We measure abnormal returns by

estimating the market model using 200 trading days of return data ending 11 days before key legislative

events related to the passage of the Companies Act 2013. The return on National Stock Exchange’s CNX

500 index is used as a proxy for the market return. Daily abnormal stock returns are cumulated to obtain

the CAR from day t − 1 before the legislative event date to day t + 1 after the event date. The RDD sample is

constructed as follows. First, a binding score rating variable M is created which is defined as the minimum of

the three individual rating scores R1, R2, and R3, which are in turn defined as (Profit – 50)/50, (Book value

– 5,000)/5,000, and (sales – 10,000)/10,000, and which perfectly determines whether a firm is affected by

the mandatory CSR rule or not. Profit, book-value and sales for the most recent fiscal year end before any

event date are considered to eliminate any perfect foresight bias. The INR 50 million profits, INR 5,000

million book value, and INR 10,000 sales are the three cutoffs specified in the mandatory CSR rule. If a

firm has profit, book value, or sale above these cutoffs, the firm is then required to spend on CSR. Firms

with the variable M ranging between −0.50 and 0.50 comprise our RDD sample, where firms with M > 0 are

AFFECTED by the rule and firms with M < 0 are UNAFFECTED by the rule. The significance of median and

the difference in median values for the two subgroups is tested using Wilcoxson test. ∗∗∗ , ∗∗ , and ∗ denote

significance at 1%, 5%, and 10% level (two-tailed), respectively.

For Event # 3, when the Ministry of Corporate Affairs announced that it is

considering making only the disclosure of CSR and not the actual spending

on CSR mandatory, we expect a positive market reaction for the AFFECTED

firms because this event is likely to mitigate any possible negative effects

of the mandatory CSR rule. However, we do not observe any significant

market reaction.

Events # 4–8 are associated with increased probability of the legislation

passing. Therefore, we expect a negative market reaction for the AFFECTED

firms under the hypothesis that CSR is value-destroying. However, we find a

statistically significant negative reaction for the AFFECTED firms only for

Event # 6 when the Lok Sabha (the lower house of the Indian Parliament) passed the Companies Act (–1.6%). The other events such as the

re-introduction of the Bill in the Lok Sabha (Event# 4), submission of a revised report by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance (Event

# 5), the passage of this Bill in the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian Parliament (Event # 7), and Presidential assent to the Bill (Event# 8)

1280

H. MANCHIRAJU AND S. RAJGOPAL

are all associated with a statistically insignificant market reaction for the

AFFECTED firms.

The median CAR for the AFFECTED firms across all these eight events is

negative. Overall, these results provide initial evidence of a negative impact

of CSR on shareholder value.

4.3

GRAPHICAL ANALYSIS

Graphs provide a transparent way of showing how the treatment effect

is identified in an RDD framework. For each of the eight event dates outlined previously, we separately plot the stock market reaction for firms in

the RDD sample. Figures 3a–3h show a scatter plot that presents the stock

market reaction on significant CSR events for AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED

firms. On the X-axis is the binding score rating variable (M, in this case)

which ranges from –0.50 to 0.50, with 0 being the cutoff point. On the Y

axis is the three-day CAR around the event date. To enhance the visual impact of the graph, estimated CAR is superimposed on the plot, where CAR

is estimated as a function of the rating variable M separately on both sides

of the cutoff using local linear estimation, triangular kernel, and Imbens–

Kalyanaraman [2012] bandwidth, using the following equation:

CAR = α + τ AFFECTED + f (M ) + ε.

(3)

Because the only difference near the cutoff is that firms to the right of

zero are AFFECTED by the mandatory CSR rule whereas firms to the left of

zero are UNAFFECTED, any discontinuity in CAR at the cutoff can therefore

be attributed to the mandatory CSR rule because it imposes the threshold

and creates the discontinuity.

We use the RD command in STATA, developed in Nichols [2007], to generate this graph. Figures 3a through 3h correspond to each of the event

dates. For the sake of parsimony, we describe only three graphs. Graph 3a

relates to the Event # 1 on August 3, 2009. There is no significant jump

or drop at the cutoff point suggesting that the average CAR for the AFFECTED and UNAFFECTED firms on this date are statistically indistinguishable. Graph 3b relates to the Event # 2 on August 31, 2010. At the cutoff

point, the fitted curve on the right is significantly lower that the fitted curve

to the left. The only difference near the cutoff is that firms to the right of

zero are AFFECTED by CSR rule whereas firms to the left of zero are UNAFFECTED. Hence, this discontinuous drop in the fitted curve (that captures

firm value) at the threshold can be attributed to the mandatory CSR rule

which imposes the cutoff and creates the discontinuity. Based on this graph

3b, we infer a negative relation between CSR and firm value. Using the

same logic, we find a negative relation between CSR and firm value in Figure 3f that relates to the Event # 6 on December 18, 2012. However, all

the remaining graphs suggest that the market reaction for the AFFECTED

and UNAFFECTED firms on the remaining event dates are statistically

indistinguishable.

IMPACT OF CSR ON SHAREHOLDER VALUE

(b)

3-day CAR around Event# 2 - 08/31/2010

-.5

0

.5

-.06

-.04

-.04

-.02

-.02

0

0

.02

.02

.04

.04

.06

.06

(a)

3-day CAR around Event# 1 - 08/03/2009

1281

-.5

0

(d)

3-day CAR around Event# 4 - 12/14/2011

-.5

0

.5

-.06

-.06

-.04

-.04

-.02

-.02

0

0

.02

.02

.04

.04

.06

.06

(c)