Mediation Approaches in Malawi: Conflict Resolution & Peacebuilding

advertisement

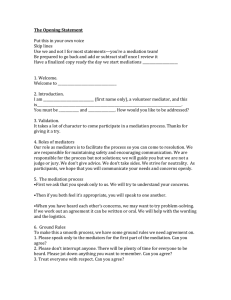

Mediation: No One Size Fits All

Master Dicks Mfune

Development Studies PhD candidate, MPM, BA (HRM0, Dip. in Management Studies.

Malawi Institute of Management, Blantyre Campus, Malawi

Telephone: +265 (0) 888875938/ (0) 999697514, Email: masterdicksmfune@gmail.com

Abstract

This paper analyses the different approaches to mediation in Malawi. As conflicts keep on increasing,

and getting more challenging, the practice of peacebuilding and resolving conflict must evolve to keep

pace. Today’s conflicts are chaotic and protracted intra-state affairs and mediation is no longer

primarily the business of the state. More than ever, both conflict and peace feature an intricate web of

actors, and can happen concurrently at different levels. These, therefore, call for creative and flexible

responses. Disputes and violent conflicts impinge on the attainment of development outcomes as

espoused by Malawi 2063 Enabler 2: Effective Governance Systems and Institutions and sub-theme

sustainable peace and security. Sustainable peace and security is crucial for the creation of a sound,

competitive and equitable environment for economic development. Sustainable development will not

happen without peace and national security. Therefore, mediation, as an alternative dispute

mechanism, plays a pivotal role in maintaining a peaceful Malawi that attracts and retains investors;

provides access to justice and effective remedies in creating an inclusively wealthy and self-reliant

nation. This paper is based on literature review and empirical evidence collected through largely

qualitative research design. The study revealed that there are seven approaches to mediation: (i)

facilitative or traditional, (ii) court mandated, (iii) evaluative, (iv) transformative, (v) med-arb, (vi)

arb-med, and (vii) e-mediation. The analysis of empirical evidence shows that there are; (a) insider

(local) mediators like dare, abunzi, gacaca, sangweni in Rwanda, Zimbabwe and Malawi, (b) outsider

(international).mediators, and (c) combination of insider and outsider mediators. One-size-fits-all

(mediation approach) peacebuilding is a risky and ultimately futile business. Applying one best fit

mediation approach across conflicts rarely works. Furthermore, short-term international interventions

are proving insufficient to address today’s conflicts. Ultimately, there is no substitute for local

knowledge and strong relationships on the ground. To paraphrase the old saying, trust takes mere

seconds to break, and forever to repair – but it is built up over years. Neutral ‘outsiders’ are thus

assumed to fit the mould best. In many disputes of the world, however, communities in conflict prefer

to deal with insiders who know the situation, have established relationships of trust, and stay

committed. In addition, outside intervention of any kind is not always possible, nor desired. For these

reasons, sustainable peace often depends on the involvement of people who are part of the conflicted

society’s fabric. Sadly, insider mediators’ contributions often go unrecognised, as international

attention is drawn to the more visible, ‘glamorous’ aspects of high-powered diplomacy. Best approach

to mediation is contingent upon the context and level of the conflict.

Keywords: alternative dispute resolution, conflict, dispute, mediation, peacebuilding

Introduction

Peacebuilding in the post–Cold War era is a nonlinear process due to the complexity of

protracted conflict and violence involving nonstate groups as well as regional and

international actors. Despite the decrease in the number of war deaths since 1946, conflict

and violence are currently on the rise, with many conflicts today waged between nonstate

actors such as political militias and criminal and international terrorist groups (UN 2020),

resulting in a massive scale of forcibly displaced persons. The intermingling factors that have

led to these trends lie in weak governance, organized crime, fragmented opposition

movements, violent extremism, gender, youth, and natural resource management in conflict

settings. Given the above situation, mediation, understood as preventive diplomatic efforts for

peace by the international community, has been considered an effective instrument for

preventing, managing, and resolving conflicts and developing sustainable peace. The term

“mediation” entered the diplomatic arena in 1948 when the UN launched mediation efforts in

Palestine. Since then, international mediation, regardless of whether it addresses interstate or

intrastate conflicts, has mainly been undertaken by third parties or external actors, especially

as the number and intensity of intrastate conflicts have increased since the end of the Cold

War.1

Conflicts have been with man since creation. In fact, it was as a result of the conflict that God

sent away Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, in the Bible. Conflicts or disputes

engender both positive and negative responses depending on the way we treat them when

they arise. Conflict is indeed a social process which is a common and essential feature of

human existence (Amon, 2007). Conflict situations arise when individuals or groups pursue

positions, interests, needs, or values that may lead to actions that come up against the

interests, needs, and values of others when they also want to satisfy their goals. Conflict

resolution is the process of bringing disputes to an end and removing the identified causes or

triggers of conflicts and their forms of expression. Conflict resolution has set of techniques

for resolving conflicts with the assistance of a third party (DGS, 2019). Alternative dispute

resolution (ADR) is a concept that encompasses a variety of mechanisms by which conflicts

are resolved. (Amon, 2007). The main types of ADR methods are Adjudication, Mediation,

Conciliation, and Arbitration. They have a lot of similarities with the main purpose is

providing less time-consuming resolution pathways than litigation. The main purpose of

ADR methods is to reach a settlement and not direct enforcement of rights. Each method has

its advantages and disadvantages (ODR Guide, 2022). Malawi’s commitment to non-violent

means of resolving conflicts is specifically provided for in section 13{1) of the Constitution

as one of the principles of national policy, which states that “the state shall strive to adopt

“mechanisms by which differences are settled through negotiation, good offices, mediation,

conciliation and arbitration” (GoM, 1995)

However, mediation is said to be the most preferred approach to ADR (Sharp, 2017).

Mediation is a third-party intervention process that aims at helping the parties to a dispute

reconcile their difference, reach a compromise and attain a settlement of their conflict. In

1

M. Taniguchi (2022) Japan International Cooperation Agency, Tokyo, Japan e-mail:

Taniguchi.Miyoko@jica.go.jp

mediation, a neutral third party tries to help disputants resolve disagreements and negotiate a

settlement. Mediation focuses on the interests, needs, and rights of the parties to the conflict

(DGS, 2019). There are two types of mediation or people that are mediators involved in

mediation, namely international also known as an outsider, and local or internal known as an

insider. The mediator manages the interaction between the parties and facilitates open

communication and dialogue. Usually, parties to a conflict accept that they have a conflict

situation and are willing and committed to resolving it (DGS, 2019). Reflecting on the above,

conflict resolution literature has emphasized the roles of international or outsider mediation,

while little research has focused on internal or insider mediation (Taniguchi, 2022). Wehr

and Lederach (1991) first developed the concept of “insider-partial” mediators within

conflicts who benefit from a certain connectedness to and a high degree of trust from the

conflict parties. Svensson and Lindgren (2013) further elaborated the role of insider-partial

mediators who bring important indigenous resources to a peace process and can thus

complement external mediators by mitigating the bargaining problem of information failure.

Despite the recognition of the importance of insider mediation for sustainable peace, it has

not been a focus in academia because it is difficult for outsiders to obtain data and

information that are politically sensitive or confidential in a transitional setting in order to

understand such a complex process. Most networks, which are considered the fundamental

infrastructure of insider mediation, are informal or personal, requiring outsiders to apply an

adaptive approach reflecting local power dynamics and social relations among individuals

and groups at the national and local levels. In addition to the lack of studies that have

examined “insider mediation,” it is scientifically or methodologically difficult to prove the

outcome and effectiveness of the practice, as peacebuilding itself is a complex and

continuous process that has no clear end or stopping point (Taniguchi, 2022).

To encourage effective mediation, the UN issued The United Nations Guidance for Effective

Mediation in 2012 as an annex to the report of the secretary-general on Strengthening the role

of mediation in the peaceful settlement of disputes, conflict prevention and resolution

(A/66/811, June 25, 2012) (UNSC 2012), identifying key fundamentals1 based on case

studies. However, third-party or external mediation has not always been successful under

political transition settings in conflict-affected countries in which society is divided and there

is weakened social cohesion and trust. As observed in the cases of Colombia, Myanmar,

Syria, Libya, and Yemen, mediation and other forms of third-party involvement appear to be

challenging (Baumann and Clayton 2017) and limited in their ability to address the complex

and interdependent dynamics of conflicts at the national and local levels.

This paper discusses seven styles of mediation, facilitative, court-mandated, evaluative,

transformative, med-Arb, arb-med, and e-mediation (Shonk, 2022; OMA, 2022), and two

approaches of mediation, namely, outsider and insider mediation also known as traditional

approaches2, other call them institutions such as the dare3 in Zimbabwe, abunzi4 and the

2

UNECA organised its Fourth African Development Forum (ADF IV) under the theme Governance for a

Progressing Africa. The forum brought together key stakeholders as a means of stimulating debate and

building consensus, identifying key and new areas for policy research and advocacy.

3

Zartman, I.W. 1999. Introduction: African traditional conflict “medicine”. In: Zartman, W.I. ed. Traditional

cures for modern conflicts. African Conflict “medicine”. Boulder, CO, Lynne Rienner. pp. 1–11.

gacaca5 courts of Rwanda, the bashingantahe6 in Burundi, Public Affairs Committee (PAC)7,

and Sangweni8 in Malawi, Presidential Prayer Breakfast in Kenya9 and Malawi10 continue to

play tremendous roles in conflict resolution. These institutions have presided over cases such

as land disputes, civil disputes and, in some instances, criminal cases. In countries like

Rwanda, these traditional institutions of dispute resolution are fully recognised under the law,

while in other countries such methods exist extra-judicially., and seven approaches to

mediation. The seven approaches of mediation are facilitative, court-mandated, evaluative,

transformative, med-Arb, arb-med, and e-mediation (Shonk, 2022; OMA, 2022). While all

mediators work to help parties resolve conflict, mediators use a variety of styles and

approaches to do this. Much like doctors and counsellors will use different strategies to

achieve desired results, so too do mediators use different techniques (OMA, 2022). The

paper uses case studies of traditional approaches of dare courts in Zimbabwe, Abunzi and

gacaca in Rwanda, bashingantahe in Burundi Public Affairs Committee (PAC), and Sangweni

in Malawi, Presidential Prayer Breakfast in Kenya and Malawi. These traditional approaches

4

The abunzi is a mediation committee located at the cell level in Rwanda. The abunzi is one of the institutions

that seek to resolve disputes locally. abunzi mediators are mandated by statutory law to resolve disputes via

mediation.

5

Gacaca is a local court in Rwanda which is made up of locally elected judges called inyangamugayo who are

chosen on the basis of their integrity. Although they existed in pre-colonial times, gacaca courts were

reincarnated in post-genocide Rwanda and mandated by the state to try cases of crimes committed during the

1994 genocide.

6

Bashingantahe is a traditional institution in Burundi, comprising a body of local people vested with social,

political and judicial power to resolve conflicts.

7

Formed in 1992 during the Malawi’s political transition from one party to multi-party system of government,

the PAC remains a key civil society organization in the field of human right, mediation, advocacy, religious coexistence, electoral processes and peace and security

8

A Ngoni word meaning “at the gate”. In Old Biblical times, important and Ngoni culture decision by the

elders of the village, clan or tribe were being made at the gate of kraal. This is the concept, Centre of

Peacebuilding and Conflict Management (C4PCM) advocated for mediation in 2019 Presidential Election

Dispute between Lazarus Chakwera and Saulosi Chilima against Electoral Commission and Malawi

Government.

9

Prayer Breakfast, a culinary diplomacy used for dialogue and mediation. In African culture it is believed that

enemies cannot eat together in the same plate. Therefore, if you want to bring enemies to a table to

negotiate, let the food unite them. The 2019 prayer event came with a surprise as the political enemies of

2017 General Election, President Uhuru, his deputy Ruto and Opposition Leaders Raila Odinga, Kalonzo

Muyoka, buried the hatchet. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/kenya/article/2001327659/history-of-kenyasnational-prayer-breakfast.

10

However, the same culinary diplomacy failed to bring the ruling part and opposition in Malawi together

when PAC and Calvary Family Church tried to organise a Presidential Prayer Breakfast. Each of these lack

characteristics of effective mediation: consent, impartiality, inclusivity, neutrality and integrity of the

organisers. https://www.faceofmalawi.com/2019/05/08/chakwera-shun-presidential-prayers-breakfast-totake-place-at-state-house/

have used the seven styles/approaches of mediation as a single style or combination of these.

On the other hand, the paper also explains how outsider mediators have played a role in

resolving conflicts single handled or in combination with local institutions such as in

Mozambique, Kenya and Malawi at various times. However, this paper is going to only

discuss the Mozambique, Rwanda, Kenya and Malawi cases because of the space of time and

space.

Approaches to Mediation

Expert Evidence (2015) and the President and Fellows of Harvard College, (2022) discusses

approaches as types of mediation and outlines seven types of mediation. These are

facilitative, court-mandated, evaluative, transformative, med-Arb, arb-med and e-mediation.

These are discussed in the subsequent paragraphs.

Facilitative Mediation

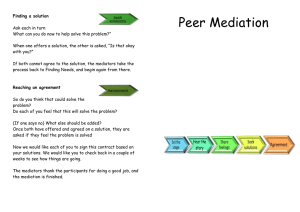

In facilitative mediation or traditional mediation, a professional mediator attempts to facilitate

negotiation between the parties in conflict. Rather than making recommendations or imposing

a decision, the mediator encourages disputants to reach their own voluntary solution by

exploring each other’s deeper interests. In facilitative mediation, mediators tend to keep their

own views regarding the conflict hidden.

Court-Mandated Mediation

Although mediation is typically defined as a completely voluntary process, it can be

mandated by a court that is interested in promoting a speedy and cost-efficient settlement.

When parties and their attorneys are reluctant to engage in mediation, their odds of settling

through court-mandated mediation are low, as they may just be going through the motions.

But when parties on both sides see the benefits of engaging in the process, settlement rates

are much higher (The President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2022). Expert Evidence,

2015). Recently, a Court-Mandated mediation was used to settle the intra-party dispute

involving Nankhumwa and Chaponda as to who is the leader of the Opposition, Justice

Kenyatta made his determination that Nankhumwa remains the Leader of Opposition. And

after the Court-Mandated Meditation both parties to the dispute agreed to the decision and

reconciled. As Magalasi11 (2020) wrote “Dust settles in DPP as it maintains Nankhumwa as

Leader of Opposition”.

Evaluative Mediation

Standing in direct contrast to facilitative mediation is evaluative mediation, a type of

mediation in which mediators are more likely to make recommendations and suggestions and

to express opinions. Instead of focusing primarily on the underlying interests of the parties

involved, evaluative mediators may be more likely to help parties assess the legal merits of

their arguments and make fairness determinations. Evaluative mediation is most often used in

court-mandated mediation, and evaluative mediators are often attorneys who have legal

expertise in the area of the dispute.

11

Magalasi, C., (2022). Dust settles in DPP as it maintains Nankhumwa as Leader of Opposition”.

https://malawi24.com/2022/09/23/dust-settles-in-dpp-as-it-maintains-nankhumwa-as-leader-of-opposition/

Transformative Mediation

In transformative mediation, mediators focus on empowering disputants to resolve their

conflict and encouraging them to recognize each other’s needs and interests. First described

by Robert A. Baruch Bush and Joseph P. Folger in their 1994 book The Promise of

Mediation, transformative mediation is rooted in the tradition of facilitative mediation. At its

most ambitious, the process aims to transform the parties and their relationship through the

process of acquiring the skills they need to make constructive change.

Med-Arb

In med-arb, a mediation-arbitration hybrid, parties first reach agreement on the terms of the

process itself. Unlike in most mediations, they typically agree in writing that the outcome of

the process will be binding. Next, they attempt to negotiate a resolution to their dispute with

the help of a mediator. If the mediation ends in an impasse, or if issues remain unresolved,

the process isn’t over. At this point, parties can move on to arbitration. The mediator can

assume the role of arbitrator (if he or she is qualified to do so) and render a binding decision

quickly based on her judgments, either on the case as a whole or on the unresolved issues.

Alternatively, an arbitrator can take over the case after consulting with the mediator.

Arb-Med

In arb-med, another among the types of mediation, a trained, neutral third party hears

disputants’ evidence and testimony in an arbitration; writes an award but keeps it from the

parties; attempts to mediate the parties’ dispute; and unseals and issues her previously

determined binding award if the parties fail to reach agreement, writes Richard Fullerton in

an article in the Dispute Resolution Journal. The process removes the concern in med-arb

about the misuse of confidential information, but keeps the pressure on parties to reach an

agreement, notes Fullerton. Notably, however, the arbitrator/mediator cannot change her

previous award based on new insights gained during the mediation.

E-mediation

In e-mediation, a mediator provides mediation services to parties who are located at a

distance from one another, or whose conflict is so strong they can’t stand to be in the same

room, write Jennifer Parlamis, Noam Ebner, and Lorianne Mitchell in a chapter in the book

Advancing Workplace Mediation Through Integration of Theory and Practice. E-mediation

can be a completely automated online dispute resolution system with no interaction from a

third party at all. But e-mediation is more likely to resemble traditional facilitative mediation,

delivered at a distance, write the chapter’s authors. Thanks to video conferencing services

such as Skype and Google Hangouts, parties can now easily and cheaply communicate with

one another in real time, while also benefiting from visual and vocal cues. Early research

results suggest that technology-enhanced mediation can be just as effective as traditional

meditation techniques. Moreover, parties often find it to be a low-stress process that fosters

trust and positive emotions.

Insider Mediators

Different terminology are used for insider mediators (IM). Some call them traditional

approaches, and others local mediators. This paper uses the term IM to mean traditional

approaches or institutions in mediation. An Insider Mediator (IM) is described as“an

individual or group of individuals who derive their legitimacy, credibility and influence from

a socio-cultural and/or religious – and, indeed, personal - closeness to the parties of the

conflict, endowing them with strong bonds of trust that help foster the necessary attitudinal

changes amongst key protagonists which, over time, prevent conflict and contribute to

sustaining peace. ”The term insider mediator is preferred to alternative definitions that have

been proposed by the field, such as ‘partial-insider’ or ‘local mediator’ since, as this will

show, IMs are only ‘partial’ in certain respects. In addition, IMs may originate from and work

at local, national, and/or regional levels, whereas the term ‘local’, is often used

synonymously with the word ‘community’ or ‘grassroots.’ The potential areas where IMs

may be acknowledged and/or supported include but are not limited to: peace processes;

political disputes; electoral-related violence; natural resource-related conflicts; humanitarian

crises; preventing violent extremism; identity conflicts; intra-group tolerance; and, diverse

community-level issues. It is argued that for as long as societies have experienced clashes of

positions and interests leading to tensions and/or conflict, IMs – community leaders, elders,

political or religious figures, rebel/military commanders, teachers, doctors, business leaders,

academics, writers and artists, amongst others- have played the role of an IM, shuttling

between and within fractured groups, leveraging their relationships and seeking to exert a

level of influence that may make the difference, over time, between conflict and peace

(UNDP, 2020).

Achieving the Malawi 2063 vision of creating an inclusively wealthy and self-reliant nation

requires Enabler 2: Effective Governance Systems and Institutions, specifically, sustainable

peace and security (NPC, 2020), will require a significant and sustained investment of human

and financial resources by all players, as well as a Ministry’s commitment to preventing

violent conflict and promoting peace. The political will to make this happen is strong.

Another, more subtle but equally significant, the investment will also be necessary to

strengthen the ‘collaborative capacity of societies. At the national level, this expresses itself

as the ability to collaborate across political and social boundaries to push forward critical

reforms, work together with people from different cultural background, races, creed, religions

and regions in the public interest and address emerging risks or disputes peacefully. At the

local level, collaborative capacity is reflected in levels of social cohesion and the ability of

communities to live and work together in shared spaces. Without this capacity, the consensus

and coalitions that underlie the meaningful change and critical reforms necessary (Fiedrich,

Nes and Okai, 2018 in UNDP, 2020) to achieve the Malawi 2063 (NPC, 2020) cannot be

attained, nor can peace be sustained. This capacity is partly reflected in the institutions, both

international and IM, that mediate consensus and peaceful change, whether parliamentary

committees, local peace councils, national reconciliation commissions or forums of elders.

Critically, it is also reflected in the roles and work of trusted intermediaries —‘insider

mediators’— who bring influence, legitimacy, courage and unique skills to trigger the

changes in attitudes and behaviours required for meaningful transformation, often mediating

differences before tensions erupt into violence (Fiedrich, Nes and Okai,2018 in UNDP,

2020).

Outsider Mediators

One of the procedures for the peaceful settlement of international disputes is mediation,

which is the direct participation by a third country, individual, or organization in resolving a

controversy between states. The mediating state may become involved at the request of the

parties to the dispute or on its own initiative. In its role as mediator the intervening state will

take part in the discussions between the other states and may propose possible solutions. A

related procedure is the offer of good offices, where a state will take various actions to bring

the conflicting states into negotiations, without necessarily taking part in the discussions

leading to settlement.12 In the In Mozambique long civil war, international mediation has

been used to resolve the conflict.

Facilitation process of Mediation in Mozambique

In the past and present, Mozambique as a case in the Southern Africa Development

Community (SADC) has used both the international and traditional approaches in a bid of

resolving the conflicts it faces. It has also used the adaption of the facilitation process to

approach. These approaches have had some successes but also faced some challenges.

Mozambique has faced several cycles of violent conflict since the independence war against

Portuguese rule (1964–1974), followed by a long civil war (1977–1992) between FRELIMO

(Mozambique Liberation Front) and RENAMO (Mozambican National Resistance), and its

recent recurrence (2012–2022). Decades of peace negotiations have followed, resulting in

three main peace agreements: the 1992 General Peace Agreement (GPA), the 2014

Cessation of Military Hostilities Agreement (CMHA), and the 2019 Maputo Accord for Peace

and Reconciliation (MAPR)13. After the 1992 GPA, numerous peacebuilding programs have

been implemented by various actors, ranging from traditional international donor such as

the G19 group1 to donors that have emerged in the last 15 years, for example China, Brazil,

India, Vietnam, and the Gulf Countries (de Carvalho, Rozen, and Reppell, 2016,). From 1992

to 2012, Mozambique’s peacebuilding process was hailed as a successful case of liberal

peacebuilding, resulting from a successful mediation process led by a faith-based mediator,

the lay Catholic association Community Sant’Egidio.

The Mozambican government and RENAMO used international mediation, and this

mediation strategy was a success that led to the 1992 GPA (Lusa News Agency, 2016c). The

Mozambican government nominated the following mediators: Ketumile Masire, former

president of Botswana, linked to the Global Leadership Foundation (GLF), along with Robin

Christopher; Jakaya Kikwete, former president of Tanzania, represented by Ibrahim

Msambaho; and the African Governance Initiative (AGI), linked to former British Prime

Minister Tony Blair, represented by Jonathan Powell of InterMediate (UK). RENAMO

appointed three mediators, namely the EU, which was represented by Mario Raffaelli (former

mediator in the 1992 peace process) and Monsignor Ângelo Romano (Community of

Sant’Egidio); the Vatican, represented by the Apostolic Nuncio in Maputo, Monsignor Edgar

12

West’ Encyclopedia of American Law (2008). Mediation, International Law, https://legaldictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Mediation%2c+International+Law#:~:text

13

Saraiva, R., (2022). JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development, Tokyo, Japan e-mail:

Farosaraiva.Rui@jica.go.jp

Pena, and the secretary of the Episcopal Conference of Mozambique, Auxiliary Bishop of

Maputo, Dom João Carlos Hatoa Nunes; and the South African president Jacob Zuma,

represented by Mandlenkosi Memelo and George Johannes of the Ministry of Foreign

Affairs. Forty-seven sessions of negotiations were held by the Joint Commission and the

international mediators in the five-star “Avenida Hotel” in Maputo (Reis 2017; Lusa News

Agency 2016b; Hanlon 2016; Weimer and Carrilho, 2017).

By August 2016, the international mediation team’s leader, Mario Raffaelli (representing the

EU), noted the lack of immediate progress, as both parties were just “discussing …

discussing … discussing” with no practical achievement, denoting an environment of extreme

uncertainty after few rounds of international mediation. The head of the RENAMO’s

delegation at the time, José Manteigas, mentioned that one of the most contentious issues on

the negotiation table was the appointment of RENAMO provincial governors in six provinces

(Saraiva, 2022).

The work of the decentralization subcommittee was extensive. It aimed at supporting the

process of revising the Mozambican Constitution and a number of different laws: (1) the law

related to the reform of the state, (2) the law on provincial assemblies, (3) the basic law of the

organization and functioning of public administration, (4) the law empowering local district

authorities, (5) and the approval of the law of governing bodies and the (6) law of provincial

funding. This set of new laws was meant to pave the way for a peaceful electoral process.

However, the timing of this ambitious decentralization agenda was not ripe for a concrete

agreement between both parties. RENAMO submitted a reform package to the subcommittee,

but the lack of internal party consensus resulted in the failure of FRELIMO to submit a

complimentary or alternative proposal to the Joint Commission. Therefore, the package of

legal revisions mentioned above was not welcomed in all FRELIMO circles (Lusa News

Agency, 2016d).

Another challenge to this mediation framework was the lack of coordination between the two

subcommittees on matters related to procedures, contents, and calendars, as well as the large

presence of mediators, many of them non-Portuguese speakers, which slowed the progress of

the negotiations. Finally, the exclusion of civil society organizations from the mediation

process, including the third major party in the Mozambican parliament, the Democratic

Movement of Mozambique (Movimento Democrático de Moçambique (MDM)), did not

allow for an alternative, more open format of negotiations, for example through the creation

of national committee for the revision of the constitution (Weimer and Carrilho, 2017)

Beginning in December 2016, a small mediation team of four members was led by the Swiss

ambassador to Mozambique, Mirko Manzoni. The other team members were Neha

Sanghrajka, mediation advisor at the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue; Jonathan Powell,

director at Inter Mediate; and Eduardo Namburete, senior lecturer at Eduardo Mondlane

University and member of parliament for RENAMO between 2005 and 2010 (Reis, 2019).

This mediation team focused on facilitating direct dialogue between the Mozambican

government and RENAMO, while promoting both parties’ self-organization and resilience

and responding in adaptive ways to the challenges that arose during the negotiations. More

importantly, this mediation style was not conditioned by past 1992 GPA mediation practices,

and it was fully committed to a nationally owned peace process.

This case seems to indicate that in contemporary complex and recurrent armed conflicts, the

effectiveness of the mediation process depends first on the resilience and adaptiveness of

both parties in the conflict, as well as the local communities and all domestic stakeholders

involved in the peace process. Second, it also depends largely on the mediators’ mindset and

the ability of the external mediators to listen to domestic actors while focusing on

understanding the culture and context of the conflict-affected situation. A mindset of

discretion and humility, and a smaller number of external mediators involved in the peace

process, contributes to building trust among all parties. Third, when this mindset is allied to a

pragmatic and adaptive approach, this will enable the mediators to face complex and

uncertain environments more effectively (Saraiva, 2022).

Abunzi Mediation in Rwanda

The Abunzi mediation in Rwanda is an illustrative example of the synergies between the state

and the local processes of conflict resolution. Literally translated, the word abunzi means

‘those who reconcile’. The abunzi are local mediators in Rwanda, who are mandated by the

state as the conciliatory approach to resolve disputes, ensuring mutually acceptable solutions

to the conflict. The abunzi mediators are chosen on the basis of their integrity, and they

handle local cases of civil and criminal nature. Currently, more than 30 000 abunzi mediators

operate in Rwanda at the cell level. In 2006, the Rwandan government passed the Organic

Law (No. 31/2006)12 which recognises the role of abunzi or local mediators in conflict

resolution. The abunzi system was popularised in the post-2000 era by the Rwandan

government as a way of decentralising justice, making it affordable and accessible. The

resuscitation of the abunzi is part of the Rwandan government’s repertoire of initiatives

designed to make justice and governance available to citizens at every level. The abunzi exist

alongside other decentralised forms of governance in Rwanda, including the gacaca courts.

By involving these other ‘political orders’13 in governance and conflict transformation

processes, governments in Africa would essentially be opening up democratic spaces for

various actors to exercise their agency in a constructive manner.

Before seeking justice in local courts, mediation by the abunzi is obligatory for local level

disputes, criminal cases and civil cases, whose property value is below 3 million Rwandese

francs.14 Like their counterpart institution of gacaca courts, which has tried more than 1

million cases of genocide, the abunzi system is inspired by Rwandan traditional dispute

resolution systems that encourage local capacity in the resolution of conflicts. In a way,

abunzi can be seen as a hybrid between state-sponsored justice and traditional methods of

conflict resolution, as it helps to address the challenges of an overburdened modern court

system.

Traditional institutions will continue to play a role in local governance, conflict resolution

and justice for various reasons. One major reason is that the state-building enterprises in

Africa have not yet succeeded in increasing robust states capable of providing public goods to

all areas; hence the state will need to devolve responsibilities to local communities. This does

not mean that the state has completely lost its status as a point of reference in governance and

security, but the reality underscores the notion that traditional institutions have a

complimentary role in the face of the diminishing influence of the state. Responding to the

overburdened modern court system in Rwanda, the abunzi system of mediation has helped to

address the question of access to justice by ordinary Rwandans, who might not be able to

afford to participate in the litigation justice environment.

Kenya Presidential Election Dispute 2019

Marita (2019) explained how the Presidential Prayer Breakfast acted as a facilitative tool in

mediation in Kenya. This was organised by local leaders in legislature and faith based

organisation. Marita says that the 2019 prayer event came with a surprise as the political

opponent of 2017 General Election, President Uhuru, his deputy Ruto and Opposition

Leaders Raila Odinga, Kalonzo Muyoka, buried the hatchet. Definitely, a lot changed owing

to the simmering rivalry between DP Ruto and ODM leader Raila that is if the prevailing

verbal attacks are anything to go by.

Malawi Presidential Election Dispute 2019

This part of discussion is taken from the unpublished research work of Mfune (2020) entitled

“Adaptive Approach to Facilitative Mediation: Insider Mediators”. Before Malawi went into

the Tripartite Elections of 2019 some scholars did an early warning sign and system analysis.

The Presidential Elections 2019 indicates that its results would not be easy to call who will

emerge a winner. They began lobbying development and cooperating partners (DCP) that

conflict sensitivity and peace education be conducted. However, the analysis and results

were rejected. The justification given was that Malawi is a peaceful nation and there was no

need to conduct such awareness to politicians and the general masses. However, when xxx

announced that Professor Arthur Peter Mutharika was the winner violence broke out in some

parts of the country, particularly in the Central and Southern Regions. A lot of lives and

property was lost and damaged. Economic activities were grossly affected. The nation was

tensed. President Chakwera of Malawi Congress Party (MCP) and Chilima of United

Transformation Movement (UTM) took the matter to the constitutional Court. This escalated

the violent conflict, the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) started those who were

seen to be supporting or sympathising with the opposition during the hearing of the

Presidential Election case.

It was during this time that it began to dawn of DCP, CSOs, FBOs business fraternity,

traditional leaders, academia, women and youth that indeed Malawi requires someone to

mediate. The DCP, through UNDP, championed by Mario Jose Torres played a vital role of

international mediator doing shuttle diplomacy. She would contact both the leaders of MCP

and UTM front runners in the opposition, and the leaders of DPP, but there seemed to be no

solution. One side of the Presidential Election dispute was questioning the impartiality of the

CDP. Impartiality is one of the fundamentals of effective mediation. The others are

preparedness, consent, inclusivity, and national ownership. On the other hand PAC and

Pentecostal Revival Crusade of Dr Apostle Madalitso Mbewe bid to reconcile the two

through Presidential Prayer Breakfast which was organised separately were not inclusively

attended by either of the parties in the dispute. This was because PAC was allegedly seen to

favouring the opposition, whilst Apostle Mbewe was seen to be favouring DPP. The Centre

for Peacebuilding and Conflict Management (C4PeaCM) in Blantyre, a faith-based

organisation, in partnership with Centre of Peace and Conflict Management (CEPCOM) at

the University of Malawi in Zomba volunteered to facilitate of the establishment of Insider

Mediators, the concept was shared with several DCP. The idea was accepted but the

response was that they would rather deal with PAC because it was credible and had a

gravitas. The joint effort of C4PeaCM and CEPCOM managed to raise a list of credible

individuals who were retired senior public officers, Ambassador Professor Brown

Chimphamba, who was Malawi’s UN Ambassador during Bingu Wa Mutharika but also Vice

Chancellor of the University of Malawi during Muluzi era, and Chairperson of Malawi

Electoral body that oversee the conducting of Referendum during Kamuzu Banda era; retired

Justice Anastasia Msosa, SC, Chief Justice of Supreme and High Court, and former

Chairperson of the Malawi Electoral Commission during the 1994 and 2004 Elections,

Ambassador Dr. Muyeriwa, High Commissioner Ziliro Chibambo, who was a former

Minister during United Democratic Front era, and late retired Justice Lovemore Munlo, who

was deputy Chief Justice but also former Minister of Justice during Dr Banda era. When the

list was presented to the two sides, they both accepted the names and consent was given that

they would mediate. However, when the concept was taken to DCP for funding, the response

was not positive. On the other hand, PAC as an Insider Mediator also played a critical role of

trying to resolve the Presidential Election 2019 dispute by trying to bring the two parties to

common ground of reaching a compromise, and Rafik Hajat wanted to bring in outsider

mediators led by Lupiya Banda his idea did not go far. These initiatives wanted these insider

and outsider mediators to facilitate the process of dialogue and negotiations in order to

resolve the conflict and restore peace that was lost due to the Presidential Election Dispute.

The Presidential Election dispute was finally referred to the Constitutional court and after

over nine months of hearing the case. Judgment was made that nullified the 2019

Presidential Election results which made Professor Arthur Peter Mutharika State President

and called for fresh elections.

The initiatives were not successful if one has to look at the ultimate outcome, that is, no

negotiation agreement was done that could be as the evidence. However, the message went

across to the disputants that Malawians want peace, and that Malawians will hold them

responsible for the outcome of the fresh presidential elections 2020

Conclusion

There is no one best way to resolve a dispute or conflict, international mediation has its own

merits and demerits, and traditional approaches or insider mediators have their strengths and

weakness. These need to work hand in hand to reinforce each other where one is strong and

the other is weak. However, context matters where one has to be used. The traditional

approaches require to be strengthened through institutionalisation, capacity building, and

financial resources. There is a need to conduct awareness campaign and mainstream

traditional approaches in conflict mechanisms in Malawi.

Recommendations

Mediation is one of the most effective methods of preventing, managing and resolving

conflicts. To be effective, however, a mediation process requires more than the appointment

of a high-profile individual to act as a third party. Antagonists often need to be persuaded of

the merits of mediation, and peace processes must be well-supported politically, technically

and financially. Ad-hoc and poorly coordinated mediation efforts – even when launched with

the best of intentions – do not advance the goal of achieving durable peace (2012). This

paper recommends the following to the various stakeholders. .

For governments and policy makers

Create mechanisms for interaction that would encourage synergies between modern systems

and endogenous methods of conflict resolution.

Facilitate codification of traditional laws and institutions to enable a clear definition of the

roles, mandates, and boundaries of such institutions.

Building capacity of traditional institutions involved in mediation

Funding of traditional institutions

For civil society, think tanks and academic institutes

Raise scholarly and practical awareness about traditional institutions of conflict resolution

through research, documentation, debate and training.

Facilitate increased collaboration between traditional and modern institutions through

exchange missions, training and joint initiatives.

Mainstream the themes of indigenousness and local capacity in conflict intervention

initiatives.

References

Accord The Abunzi Mediation in Rwanda, Opportunities for Engaging with Traditional

Institutions

of

Conflict

Resolution,

Policy

Brief,

Mediation,

https://www.accord.org.za/publication/the-abunzi-mediation-in-rwanda/

ODR, (2022). What are the Main Types of Alternative Dispute Resolution – ADR,

https://ordguide.com/types-of-adr-adjudication-mediation-concilaition-and-arbtration/#

Expert Evidence, (2015), Different Approaches

evidence.com/different-approaches-to-mediation/

to

Mediation.

https://expert-

The President and Fellows of Harvard College (2022). 7 Types of Mediation,

https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/mediation/types-mediation-choose-type-best-suitedconflict/

Fisher and Phillips, LLP., (2017). Seven (Sometimes Surprising) Facts About Mediation,

https://www.fisherphillips.com/news-insights/seven-sometimes-surprising-facts-aboutmediation.html#:

OMA (2022). Mediation Styles, https://ormediation.org/?s=styles+of+mediation

Sharp,

G.

(2017).

Mediation

Most

Preferred

https://www.mediate.com/mediation-most-preferred-form-of-adr/

Form

of

ADR,

Carvalho, Gustavo de, Jonathan Rozen, and Lisa Reppell. 2016. Planning for Peace: Lessons

from Mozambique’s Peacebuilding Process. Institute for Security Studies (ISS).

https://issafrica.org/research/papers/planning-for-peace-lessons-from-mozambiquespeacebuilding-process.

Division of General Studies, (2019). Introduction to Peace and Conflict, Chukwuemeka,

OdumegwuOjukwa University, Igbraim campus

Government of Malawi, (1995). National Peace Policy, Lilongwe, Government Printer

Government of Malawi, (1995). Republic of Malawi Constitution, Lilongwe, Government

Printer

Government of Malawi, (2004). Government Notice No. 9, Courts Act, (Cap. 3:02), Courts

(Mandatory Mediation) Rules, 2004, Zomba, Government Printer

Hanlon, Joseph, (2014). Novo director do Observatório Eleitoral [New Director of the

Electoral

Observatory].

https://www.open.ac.uk/technology/mozambique/sites/www.open.ac.uk.technology.mozambi

que/files/files/ Elei%C3%A7%C3%B5es_Nacionais_31-24deJulho_Observat%C3%B3rio_

Eleitoral.pdf.

Lusa News Agency. (2016a). Observadores internacionais para cessar-fogo em Moçambique?

[International

Observers

in

Mozambique

for

a

Ceasefre?]

DW.COM.

https://www.dw.com/pt-002/observadores-internacionais-paracessar-fogo-emmo%C3%A7ambique/a-19503402

NPC (2020). Malawi’s Vision, Malawi 2063 – Transforming Our Nation, NPC, Lilongwe.

Reis, B., (2017). Moçambique, segundo ‘round’: mais 60 dias à procura da paz

[Mozambique, Second Round: 60 More Days in Search of Peace]. PÚBLICO Newspaper.

https://www.publico.pt/2017/03/03/mundo/noticia/

mocambique-segundo-round-mais-60dias-a-procura-da-paz-1763813.

United Nations, (2012). United Nations Guidance for Effective Mediation (A/66/811, 25 June

2012). United Nations, New York,

UNDP, (2020) Engaging with Insider Mediators, Sustaining peace in an age of turbulence,

New York, UNDP

Weimer, Bernhard, and João Carrilho, (2017). A economia política da descentralização em

Moçambique: dinâmicas, efeitos, desafos [The Political Economy of Decentralization in

Mozambique: Dynamics, Effects, and Challenges]. Maputo: IESE.