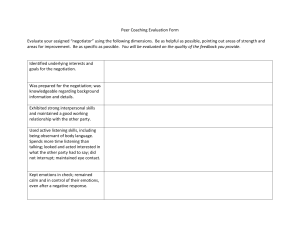

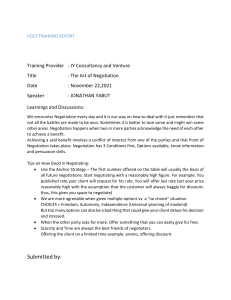

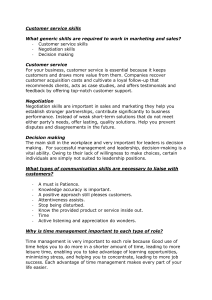

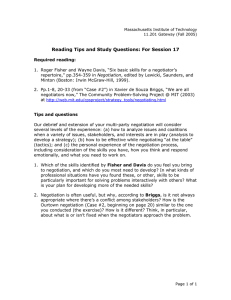

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/obhdp When we should care more about relationships than favorable deal terms in negotiation: The economic relevance of relational outcomes (ERRO) Einav Hart a, b, *, Maurice E. Schweitzer b a b George Mason University, United States University of Pennsylvania, United States A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Keywords: Negotiation Dual concern theory Negotiation context Service negotiation When should negotiators care relatively more about their relationships with their counterparts than about the deal terms? We introduce a new dimension to characterize negotiation contexts to answer this question: the Economic Relevance of Relational Outcomes (ERRO). ERRO reflects the extent to which the total economic value of a negotiation hinges on the strength of a negotiator’s post-negotiation relationship with their counterpart. For example, in hiring a tutor, a student may derive economic value from both the wage and the quality of the tutor’s post-agreement service; if the student’s post-negotiation relationship with the tutor influences the quality of the service, this negotiation context is high ERRO. Importantly, although ERRO is an objective feature of the negotiation context for each negotiator, individuals may perceive their negotiation context to have higher or lower ERRO than it actually does. Across four experiments (N = 1601), we identify ERRO as a fundamental dimension of negotiation contexts. We find that in high ERRO contexts (e.g., many services, such as hiring a tutor) compared to low ERRO contexts (e.g., buying a couch), individuals negotiate more collaboratively, are more likely to privilege relational concerns over favorable deal terms, or may even forgo negotiating altogether. Compared to negotiators who build poor relationships, negotiators who build positive relationships with their counterparts attain better economic outcomes in high ERRO contexts because their counterparts invest greater effort following the negotiation. By introducing ERRO, our work underscores the importance of post-negotiation behavior and identifies when, how, and why relational outcomes influence economic outcomes. 1. Introduction We negotiate for many consequential outcomes in our professional and personal lives. A large and growing literature has substantially advanced our understanding of negotiators’ concerns, strategies, and outcomes (Bazerman et al., 2000; Brett et al., 2007; Gunia et al., 2016; Novemsky & Schweitzer, 2004; Raiffa, 1982; Thompson et al., 2010). This work has identified economic concerns and relational concerns as two key dimensions of the negotiation process (Carnevale & Pruitt, 1992; Curhan et al., 2006; Gunia et al., 2011; Pruitt, 1998). These “dual concerns” are often conceptualized as separable and even orthogonal (e. g., Carnevale & Probst, 1998; Carnevale & Pruitt, 1992; Pruitt & Rubin, 1986; Van Lange, 1999). Although prior work has found that negotiators who prioritize relational concerns choose different negotiation strate­ gies and develop better relational outcomes than those who do not, no prior work has identified contextual features of a negotiation that might influence why or when negotiators might prioritize relational concerns. In our investigation, we introduce a novel dimension to characterize negotiation contexts: the Economic Relevance of Relational Outcomes (ERRO). We conceptualize ERRO as a continuum that reflects the extent to which a negotiation counterpart’s post-negotiation behavior can in­ fluence a negotiator’s overall (“final”) economic outcome. ERRO is a fundamental dimension of every negotiation context for every negoti­ ator and determines when, how, and why negotiators should privilege relational outcomes relative to favorable deal terms. Consider a party planner who negotiates with a caterer. The party planner might care not only about obtaining favorable deal terms but also about their relationship with the caterer, because a poor relation­ ship may diminish the caterer’s motivation and consequently harm the quality of the service the caterer delivers, which ultimately yields a poor economic outcome. Conversely, a buyer who negotiates for a new out­ door BBQ grill may be relatively unconcerned about their relationship with the seller since this relationship – and the seller’s post-negotiation motivation to help the buyer – may not impact the quality of the BBQ * Corresponding author at: George Mason University, 4400 University Drive MSN 5F5, Fairfax VA 22030-4022, United States. E-mail address: ehart8@gmu.edu (E. Hart). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2021.104108 Received 31 July 2020; Received in revised form 8 November 2021; Accepted 16 November 2021 Available online 12 December 2021 0749-5978/© 2021 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 grill. In these examples, we characterize the catering negotiation as high ERRO for the party planner, and the BBQ grill negotiation as low ERRO for the buyer. In general, negotiations for service purchases (e.g., catering) are likely to be characterized by higher ERRO than negotiations for product purchases (e.g., BBQ grill). Often, however, negotiations for products involve a service component. For example, when purchasing a new grill (a product), how the grill is delivered and assembled (a service deter­ mined by the counterpart’s motivation) might matter. As a result, we conceptualize ERRO as continuous and highly context dependent; it cannot simply collapse onto a service-product dichotomy. In contrast to prior negotiation scholarship that has used deal terms to represent economic outcomes, we conceptualize the total economic value negotiators derive from a negotiation to include both deal terms (e.g., how much an employer pays in wages) and post-negotiation behavior (e.g., how hard the employee works after receiving that wage), which may depend on the relationship between negotiators. Of course, negotiators may generally derive utility from developing a positive relationship, but in contrast to prior work that has considered relational outcomes, ERRO identifies how, when, and why relational outcomes impact economic outcomes across negotiation domains and roles. That is, no prior work has considered how a structural feature of the negotiation context might influence the economic value a negotiator derives from developing a positive relationship. We define “high ERRO” contexts as domains in which a counterpart’s post-agreement motivation and behavior can substantially change the economic value that a negotiator derives from the negotiation. That is, high ERRO contexts occur when there is a strong relationship between negotiators’ relational outcomes and their economic outcomes. For example, consider a manager who negotiates with a new recruit. The economic value the manager derives from the negotiation is not simply reflected by the deal terms; instead, a great deal of the economic value the manager derives from the negotiation occurs after the negotiation concludes. As a result, the relationship the manager and recruit develop through the negotiation may influence the recruit’s post-negotiation motivation, and ultimately influence the manager’s economic outcome.1 We define “low ERRO” contexts as exchanges in which a negotiator’s counterpart’s post-agreement motivation can only weakly, if at all, in­ fluence the economic value the negotiator derives from the negotiation. That is, in low ERRO contexts, negotiator’s relational and economic outcomes are only weakly related. This conceptualization of ERRO reflects an objective relationship. That is, in objectively high ERRO contexts, a negotiator’s relational outcomes significantly influence their economic outcomes, and in objectively low ERRO contexts they do not. Importantly, however, ne­ gotiators’ perceptions of ERRO may diverge from the objective reality. In developing our theoretical framework, we consider the possibility that negotiators’ subjective perceptions of ERRO – the extent to which the negotiator believes that a good relationship will or will not influence their final economic outcome – may diverge from objective ERRO. That is, we distinguish objective ERRO from perceived ERRO. In Fig. 1, we depict how perceived ERRO influences negotiators’ concerns and behavior. We assert that a negotiator’s perceived ERRO will influence their negotiation strategy and behavior as they assess the relative importance of privileging relational versus deal term concerns. In Fig. 2, we depict how objective ERRO moderates the relationship between relational outcomes and post-negotiation economic outcomes. We conceptualize economic outcomes to include both deal terms (e.g., Fig. 1. Perceived Economic Relevance of Relational Outcomes (Perceived ERRO), Negotiator Concerns, and Negotiation Behavior. Note. The Economic Relevance of Relational Outcomes (ERRO) is a fundamental dimension of the negotiation context for each negotiator: a continuum that reflects the extent to which the negotiator’s relational outcome influences their final, postnegotiation economic outcome. We expect each negotiator’s perception of ERRO to influence the extent to which they privilege relational concerns rela­ tive to deal terms when they negotiate. A negotiator’s perception of ERRO is likely to be influenced by their role and individual characteristics. Fig. 2. Economic Relevance of Relational Outcomes (ERRO) and Negotiation Outcomes. Note. The Economic Relevance of Relational Outcomes (ERRO) moderates the influence of a negotiator’s relational outcome with their final, post-negotiation economic outcome. ERRO is context-dependent and can vary across negotiators within the same negotiation. For example, when negotiating with a babysitter, the negotiation may be high ERRO for the parent, but low ERRO for the babysitter. In high ERRO contexts, a negotiator’s relational out­ comes are closely linked with their economic outcomes; in low ERRO contexts, a negotiator’s relational outcomes are only weakly linked with their eco­ nomic outcomes. wage) and post-negotiation behavior. Across four experiments (N = 1601), we document the importance of ERRO. We distinguish high ERRO from low ERRO negotiation contexts and demonstrate how negotiator behavior, deal terms, and postnegotiation behavior and outcomes differ between high and low ERRO contexts. Although little prior negotiation scholarship has considered how contextual differences might influence relational concerns, we reveal that negotiators readily recognize the economic relevance of their counterpart’s post-negotiation behavior (ERRO) and negotiate very differently in high and low ERRO contexts. Specifically, we show that in high ERRO contexts, compared to low ERRO contexts, negotiators: (1) are more concerned about their relationship with their counterpart; (2) are more likely to privilege relational concerns in their negotiation behavior: they negotiate less competitively and more collaboratively; and as a result (3) build better relationships that ultimately (4) motivate their negotiation counterparts to exert greater post-negotiation effort in ways that boost their economic outcomes. We advance our conceptualization and understanding of the nego­ tiation process in three key ways. First, perceived ERRO explains when 1 Though this assertion might sound readily apparent, it is not how prior negotiation scholarship has studied or conceptualized salary negotiations (see a substantial literature that has used cases such as “New Recruit” that has conceptualized salary negotiations as single-shot experiences that conclude with a signed deal sheet; e.g., Amanatullah & Tinsley, 2013; Curhan & Over­ beck, 2008; Wiltermuth & Neale, 2011). 2 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 and why negotiators are more or less likely to privilege relational over deal term concerns. Our work stands in sharp contrast to prior work that has either overlooked the potential relationship between relational and economic outcomes or conceptualized relational and economic concerns as distinct dimensions of negotiation outcomes (e.g., Carnevale & Probst, 1998; Pruitt & Rubin, 1986; Van Lange, 1999). By introducing the ERRO construct, we explicitly characterize when and why relational concerns and deal term concerns are relatively more important for economic outcomes. Second, we identify when and how negotiators’ relational outcomes are associated with their economic outcomes within a single negotia­ tion. This is distinct from the important influence relational outcomes can also exert on subsequent negotiations. Notably, we assert that the dominant experimental paradigm that scholars have used to study ne­ gotiations – single-shot hypothetical negotiations – has severely limited our ability to understand post-negotiation behavior. This includes postnegotiation behavior that may be directly relevant to economic out­ comes. For example, a popular negotiation simulation asks participants to assume the role of a job recruiter and a job candidate. The simulation ends when negotiators reach an agreement or an impasse, and scholars have used the negotiated deal terms to determine economic outcomes. In some cases, scholars have tried to measure relational outcomes as a separate outcome dimension. For example, negotiation scholars might conclude that expressing anger in a negotiation may improve economic outcomes but harm relational outcomes (Côté et al., 2013; Van Kleef & Côté, 2007). We assert that this paradigm and this approach fall short in approximating real-world behavior and outcomes. Specifically, we argue that in a context like a job negotiation (high ERRO), relational outcomes can profoundly influence final economic outcomes. By over­ looking what happens after the negotiation (e.g., the job candidate actually works for the company and may be poorly motivated), the existing negotiation literature has neglected to consider when, how, and why relational outcomes influence economic outcomes. By introducing ERRO, we also introduce a theoretical framework to explain conflicting findings in the existing literature. Prior work has found that relational concerns are sometimes positively related to eco­ nomic outcomes (Curhan et al., 2006, 2010; Kong et al., 2014), and other times negatively related to economic outcomes (Amanatullah et al., 2008; Beest et al., 2008; Bowles et al., 2007). We assert and demonstrate that relational outcomes are strongly (positively) related to economic outcomes in high ERRO contexts, but not in low ERRO contexts. Third, through ERRO, we fundamentally advance our understanding of subjective outcomes (Becker & Curhan, 2018; Curhan et al., 2006, 2009, 2010; Hart & Schweitzer, 2020). By introducing ERRO, we explain when and why subjective outcomes influence post-negotiator behavior and economic outcomes. That is, our investigation advances the subjective value literature by identifying when and why subjective outcomes matter. in negotiation (e.g., Carnevale & Probst, 1998; Pruitt & Rubin, 1986; Van Lange, 1999). Negotiation scholarship has assumed that negotiators are very con­ cerned about their own deal terms (Bazerman & Neale, 1993; Fisher et al., 1991), and that they also often care about their relationship with the counterpart (Amanatullah et al., 2008; Bear et al., 2014; Becker & Curhan, 2018; Bowles et al., 2007; Gaspar et al., 2019; Gelfand et al., 2006; Gunia et al., 2016; Moran & Schweitzer, 2008). In a theoretical paper, Gelfand et al. (2006) suggest that negotiators may have varying levels of desire for connectedness with others (“relational self-con­ strual”), depending on negotiators’ personality characteristics and cul­ ture, as well as their existing relationship with their negotiation counterpart. For example, women are more likely than men to be con­ cerned about their relationship with their negotiation counterpart (Amanatullah, Morris, & Curhan, 2008; Bowles, Babcock, & Lai, 2007), and individuals from collectivistic, interdependent cultures (e.g., China, Japan) are more likely to be concerned about their relationships than those from individualistic cultures (e.g., USA) (Gelfand et al., 2012; Gunia et al., 2016). Notably, this work focuses on individual-level fac­ tors that might inform the importance of relational concerns. In contrast to this work, we identify ERRO as a contextual factor that reflects the negotiation domain and the negotiator’s role. ERRO explains when and why negotiators should privilege relational concerns relative over deal term concerns. We postulate that high ERRO contexts cause negotiators to become more likely to focus on their relationship with their counterpart, because the counterpart’s post-negotiation behavior exerts greater impact on the negotiator’s economic outcomes. For example, in high ERRO contexts such as hiring a tutor, compared to low ERRO contexts such as pur­ chasing educational books, negotiators will be relatively more con­ cerned about their relationship with their counterpart than about the deal terms (see Fig. 1). Hypothesis 1. Compared to contexts in which negotiators perceive low ERRO, when negotiators perceive high ERRO, they will be more concerned about developing a positive relationship with their counterpart. 1.2. Negotiation strategies Scholars typically distinguish between two broad categories of negotiation strategies: 1) Competitive or aggressive strategies that claim value and 2) Collaborative or integrative strategies that focus on un­ derstanding the other parties’ interests and creating joint value (Car­ nevale & Pruitt, 1992; Deutsch, 1973; Hüffmeier et al., 2014; Kimmel et al., 1980; Van Kleef et al., 2004; Walton & McKersie, 1965; Weingart et al., 2004). For example, competitive strategies include expressing anger (Mislin et al., 2011; Overbeck et al., 2010; Van Kleef & De Dreu, 2010) and making extreme offers (Gunia et al., 2011; Schaerer et al., 2015; Schweinsberg et al., 2012), whereas collaborative strategies include asking questions (Gunia et al., 2011; Koole et al., 2000; Pinkley et al., 1995), engaging in small-talk (Mislin et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2002; Shaughnessy et al., 2015), and expressing positive emotions (Anderson & Thompson, 2004; Van Kleef et al., 2004). Negotiators’ goals and concerns influence their strategy choices (Amanatullah et al., 2008; Carnevale & Pruitt, 1992; Curhan et al., 2008; Gelfand et al., 2006; Kimmel et al., 1980; O’Connor & Arnold, 2011; Patton & Balakrishnan, 2010; Ten Velden et al., 2009). For example, prior work has found that negotiators who have strong relational goals (e.g., women) make more generous offers and are more willing to compromise (Amanatullah et al., 2008; Howard et al., 2007; Patton & Balakrishnan, 2010). Conversely, negotiators with low relational goals are more likely to negotiate aggressively, act dominantly, and make extreme offers (Magee et al., 2007; Ten Velden et al., 2009). Prior work has also found that negotiators often anticipate the con­ sequences of their actions on their relationship with their counterpart 1.1. Negotiators’ pre-negotiation concerns Scholars have assumed that negotiators have common and competing interests. For example, Fisher et al. (1991, p. xvii) defines negotiation as “back-and-forth communication designed to reach an agreement when you and the other side have some interests that are shared and others that are opposed.” Similarly, scholars have assumed that negotiators seek to balance cooperative and competitive motives (Anderson & Galinsky, 2006; Curhan & Brown, 2012; Hart & Schweit­ zer, 2020; Schaerer et al., 2020). Carnevale and Pruitt (1992) introduced the Dual Concern model, which highlights “self-concern” and “rela­ tional-concern” (or “other-concern”) as two primary concerns for ne­ gotiators. A substantial literature has built on this classic work; although some theories allow for the co-occurrence or some correlation between concerns, this literature has largely conceptualized concern for one’s own outcome and concern for the relationship as orthogonal dimensions 3 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 determines when and why relational outcomes matter. By introducing ERRO, we also reconcile conflicting findings in the negotiation literature. A substantial literature describes a compensatory relationship between economic and relational outcomes: negotiators can achieve better economic outcomes by sacrificing relational outcomes or boost relational outcomes at the expense of economic outcomes. For example, by using competitive and aggressive tactics such as expressing anger, making an aggressive first offer, and exaggerating one’s position, negotiators can improve their deal terms (Bazerman et al., 2000; Brett et al., 2007; De Dreu et al., 2007; Friedman et al., 2004; Galinsky & Schweitzer, 2015; Gunia et al., 2016; Pinkley et al., 1994; Raiffa, 1982; Thompson et al., 2010). Yet, these tactics may harm negotiators’ re­ lationships and impressions (Bhatia & Gunia, 2018; Bottom et al., 2006; Campagna et al., 2016; Mislin et al., 2011; Schweitzer et al., 2002; White et al., 2004). Other negotiation scholarship, however, has found a positive asso­ ciation between relational and economic outcomes (Bazerman & Neale, 1991; Curhan et al., 2010; Kong et al., 2014; Morris et al., 2002; Morris & Keltner, 2000; Tinsley et al., 2002). This work has found that nego­ tiators who foster trust and build a good relationship with their coun­ terpart are more likely to attain favorable deal terms in the negotiation (e.g., Kong et al., 2014). Related work finds that individuals who develop positive relationships and reputations are more likely to sub­ sequently form beneficial partnerships and be willing to collaborate in the future (Curhan et al., 2009; Drolet & Morris, 2000; Glick & Croson, 2001; Mannix et al., 1995). These two streams of research present a puzzle. To attain the best economic outcomes, should negotiators employ assertive negotiation tactics that sacrifice relational outcomes? Or should they build re­ lationships to attain the best economic outcomes? By introducing ERRO, we answer these questions. In high ERRO contexts, negotiators who attend to relational concerns will attain better economic outcomes. In low ERRO contexts, negotiators who prioritize deal term concerns will attain the best economic outcomes. Most negotiation studies have either explicitly or implicitly assumed that the negotiated deal terms represent the economic value of the negotiation process. To date, surprisingly few investigations have considered negotiators’ post-agreement behavior (see Campagna et al., 2016; Friedman et al., 2020; Hart & Schweitzer, 2020; Mislin et al., 2011 for exceptions). Instead, the dominant experimental paradigm for studying negotiations involves a single-shot negotiation that concludes once the parties agree on a term sheet. This is true for nearly every negotiation context from purchasing cell phones to hiring a “New Re­ cruit” to “Merging Companies” (Bowles et al., 2007; Overbeck et al., 2010; Pinkley et al., 2019; Wiltermuth & Neale, 2011). Across these varied contexts, the underlying structure of the negotiation exercises is nearly identical. Importantly, in these prior negotiation studies, the exercise ends when negotiators record their negotiated outcome and specify the terms of the deal. Even for negotiation studies that explicitly consider service and employment contexts (Bowles & Babcock, 2013; Curhan et al., 2008; Curhan & Overbeck, 2008; Overbeck et al., 2010; Wiltermuth et al., 2018; Wiltermuth & Neale, 2011), there is never a post-negotiation “employment” period in which negotiators’ relational outcomes and their resulting post-agreement motivation might influ­ ence the economic value of the negotiation. That is, even in contexts when relational concerns are almost certain to influence the economic value of a negotiated agreement, prior work has overlooked this possi­ bility. This has significantly limited our understanding of negotiations. For example, prior scholarship that finds that assertive negotiation strategies enable recruiters to gain favorable deal terms with a recruit may overstate the value of employing aggressive strategies. In contrast to prior work that has either overlooked the importance of relational concerns or found inconsistent relationships between relational concerns and economic outcomes, we develop a framework to explain when and how relational outcomes matter. By introducing ERRO, we explicate the relationships among relational outcomes, post- (Bear & Segel-Karpas, 2015; Curhan et al., 2008; O’Connor & Arnold, 2011; Patton & Balakrishnan, 2010). For instance, women often expect that initiating a negotiation and negotiating aggressively will harm their relational outcomes (Amanatullah & Morris, 2010; Babcock et al., 2006; Bowles et al., 2007, 2019). As a result of both increased relational concerns and expected backlash for negotiating, women negotiate less often than men, and negotiate less assertively and less aggressively when they do (Amanatullah et al., 2008; Bowles et al., 2007). Negotiators’ cultural background is also likely to influence their expectations of how competitive negotiations will be, as well as their relational goals, and consequently determine their negotiation strategies (Gelfand et al., 2012; Gelfand & Brett, 2019; Gunia et al., 2011, 2016; Rudman & Fairchild, 2004). Taken together, prior work suggests that negotiators choose collab­ orative strategies to promote relational outcomes. Thus, the more in­ dividuals care about maintaining a good relationship with their counterpart, the less likely they will be to employ competitive negoti­ ation strategies, and the more likely they will be to employ collaborative tactics. We build on Hypothesis 1, predicting that high ERRO increases negotiators’ relational concerns, to conjecture that ERRO influences negotiators’ willingness to use collaborative, rather than competitive, negotiation tactics due to heightened relational concerns (see Fig. 1). Hypothesis 2. Compared to when negotiators perceive low ERRO, when negotiators perceive high ERRO, they will be more likely to choose negotiation tactics that privilege relational gains over favorable deal terms. Hypothesis 3. Negotiators’ relational concerns will mediate the in­ fluence of ERRO on negotiator behavior. 1.3. Relational outcomes and post-negotiation behavior Mirroring the conceptualization of negotiators’ dual concerns, negotiation scholars have conceptualized two distinct types of out­ comes: economic outcomes (the terms of the deal or “objective outcome”), and relational outcomes (“subjective outcome”). Though early bargaining and negotiation scholarship focused on economic outcomes, important scholarship advanced our understanding of sub­ jective outcomes (Curhan et al., 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010; Curhan & Brown, 2012). This work maps negotiators’ subjective outcomes along three dimensions: (1) Self-perception (e.g., competence and happiness); (2) Process-perception (e.g., fairness and ease of the negotiation pro­ cess); and (3) Relational-perception, the extent to which the negotiation builds trust and a future relationship. Theoretical work often assumes that negotiators’ subjective outcomes are distinct from their objective, economic outcomes. For example, Curhan and Brown (2012, p. 586) state, “a negotiator needs to gauge which types of ends are most important.” In our investigation, we focus on relational outcomes, a key dimen­ sion of subjective outcomes. Relational outcomes are particularly likely to influence a counterpart’s post-negotiation behavior in ways that in­ fluence a negotiator’s future outcomes. For example, prior work has found that negotiators who experience greater subjective value attain better outcomes in a subsequent negotiation with the same counterpart (Curhan et al., 2010) and have lower turnover intentions (Curhan et al., 2009). This work demonstrates that subjective outcomes affect in­ tentions and behavior – and that subjective outcomes may be quite important. Missing from this line of investigation, however, is when negotiators’ subjective outcomes are more or less important. Also largely missing from prior work is the conceptualization of the negoti­ ation process as only one part of the economic relationship between counterparts. For example, even if a negotiator had no intention of ever hiring a caterer again for a future job, they may still value relational concerns in their present negotiation, because the caterer’s postnegotiation behavior will influence their economic outcomes. We identify ERRO as a critical feature of negotiation contexts and roles that 4 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 negotiation behavior, and economic outcomes (see Fig. 2). We assert that relational outcomes influence how motivated a negotiation counterpart is to assist the negotiator after the negotiation. ERRO determines the extent to which this motivation matters for the negotiator’s economic outcome. For example, an assertive car buyer who harms relational outcomes may curtail a seller’s motivation to help the buyer after the negotiation. After receiving the title and keys for the car, however, the seller’s motivation is unlikely to impact the buyer. In contrast, a buyer who harms their relationship with a caterer may harm the caterer’s motivation to help the buyer after the negotiation. In this case, the caterer’s motivation may directly impact the buyer’s economic outcome (and gastronomic wellbeing). negotiations and when participants can choose as many strategies as they wish without explicitly trading-off collaborative and competitive tactics. We preregistered all of our studies and report all experimental con­ ditions, exclusion criteria,2 and the measures we analyzed in the method section of each study. The data, preregistrations, and materials from all studies can be found in the ResearchBox online repository (https://resea rchbox.org/366&PEER_REVIEW_passcode=JWVHNH). 2. Pilot Study: High ERRO and low ERRO contexts We conducted a preregistered pilot study https://aspredicted. org/blind.php?x=bf5t2s to assess ERRO scores across negotiation con­ texts. We recruited 968 participants via Facebook Marketplace to participate in a study for $5 Amazon gift cards (425 female; Mage = 33.2, SD = 7.6).3 Each participant rated six negotiation contexts, presented in a random order. In each scenario, we asked participants to imagine that they wanted to buy a product (couch, electronic vacuum, smartphone) or hire a service provider (housecleaner, mover, tutor; see Appendix A for full text). We asked participants to imagine that they had negotiated with a counterpart (one of six different male names, e.g., “Daniel”) for this service or product. We told participants that they had agreed on a price and at the end of the negotiation they had an OK relationship with their counterpart. For each scenario (service or product), we asked two focal questions. First, we asked participants to imagine that if instead of an OK rela­ tionship, they had developed a good relationship, and to describe how that difference would impact the value of the service or product they received, on a scale from − 10: “Much Worse” to +10: “Much Better.” Second, we asked participants to imagine that if instead of an OK rela­ tionship, they had developed a bad relationship, and to describe how that difference would impact the value of the service or product they received (from − 10 to +10). For each item, we calculate ERRO as the difference between the good relationship rating and the bad relationship rating. Hypothesis 4. ERRO will moderate the link between a negotiator’s relational outcome with their counterpart and their economic outcome. Specifically, in high ERRO contexts, higher relational outcomes will be strongly associated with higher economic outcomes. In contrast, rela­ tional and economic outcomes will not be associated in low ERRO contexts. 1.4. Overview of studies Across our studies, we investigate the economic relevance of nego­ tiators’ relationships (ERRO) across different negotiation contexts: We explore how ERRO impacts negotiators’ concerns, negotiation strate­ gies, and post-negotiation behavior and outcomes. Across all four studies, we test Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, and we show that negotiators have higher relational concerns in high ERRO contexts than they do in low ERRO contexts. We demonstrate that negotiators with greater relational concerns are more likely to privilege negotiation strategies that promote relationship-building over strategies focused on attaining favorable deal terms, and we show that in high ERRO contexts these strategies improve post-negotiation economic outcomes. In our pilot study, we surveyed users of a large online marketplace and find that ERRO is higher for services than it is for products. In Study 1, we survey individuals who had purchased services and products in a second online marketplace to measure the relative importance of rela­ tional concerns and favorable deal terms across high and low ERRO contexts, and we link these concerns with negotiation behavior. In Study 2, we introduce a novel negotiation paradigm to directly test the extent to which negotiators privilege relational outcomes over favorable deal terms in high ERRO contexts. In Studies 3a and 3b, we manipulate ERRO within an incentivecompatible employment context that involves a post-negotiation stage that impacts economic outcomes. In these studies, we document important links among ERRO, relational concerns, post-negotiation effort, and economic outcomes. In Study 4, we conduct a dyadic, incentive-compatible online negotiation between bosses and workers. This study involves a post-negotiation effortful task that influences economic outcomes. In this study, we document the impact of ERRO on negotiators’ concerns, negotiator behavior, relational outcomes, postnegotiation effort, and economic outcomes. In the Supplementary Online Materials, we report three additional studies that demonstrate the impact of ERRO on participants’ preference for collaborative tactics over competitive strategies. We find very similar patterns of results when we manipulate ERRO within service 2.1. Results Consistent with our preregistration, we focus on the withinparticipant difference between the average ERRO score for the three products (Cronbach’s α = 0.859) and the average ERRO score for the three services (α = 0.867); we report means and standard deviations for each item in Table 1. Participants rated the service exchanges as substantially higher ERRO (M = 6.22, SD = 6.84) than the product exchanges (M = 5.56, SD = 6.39; paired-t(967) = 4.66, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.150). We find the same result when we regress ERRO scores for all six items by category (service or product), controlling for the item number as a dummy var­ iable, and clustering the model variance by participant to account for the repeated observations: The three services have higher ERRO than the products (B = 0.662, t(962) = 2.98, p = .003). We next analyzed the difference between services and products for 2 We preregistered and used the same exclusion criteria for each study. Specifically, we immediately excluded participants who responded they did not live in the USA, were not fluent in English, or failed an attention-check ques­ tion. Participants who failed these questions did not continue with the survey past the initial questions (and were not included in the total sample size). At the end of each study, we had a comprehension question: participants completed the study even if they failed that question. Consistent with our preregistration, we report results for participants who passed our attention checks. We note that all of our key results hold when we conduct the analyses with the full sample. 3 We preregistered a sample size of at least 300 participants, and that we would continue data collection after a week if we did not obtain that sample. On the first day of the study we substantially surpassed our intended sample size. 5 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 (from “Never” to “More than 10 times”). We defined products for par­ ticipants as “any type of object that one person owns and transfers to another in exchange for compensation. For instance, electronics, furni­ ture, cars.” We defined services for participants as “any activity that one person does for another in exchange for compensation. For instance, assembling furniture, cleaning, moving.” We next asked participants about their most recent exchange on Craigslist (purchase product, pur­ chase service, sell product, or provide service), and we focused our questions on this most recent exchange. Table 1 The Impact of the Relational Outcome on the Economic Outcome across Prod­ ucts and Services (Pilot Study, N = 968). Services (average) Cleaner Mover Tutor Products (average) Couch Vacuum Smartphone ERRO (Good - Bad) Good Relationship Bad Relationship 6.22 (6.84) 5.99 (7.76) 6.23 (7.75) 6.44 (7.79) 5.56 (6.39) 5.29 (2.90) 5.21 (3.73) 5.26 (3.69) 5.41 (3.73) 4.90 (3.02) ¡0.93 (5.41) − 0.78 (5.89) − 0.96 (6.05) − 1.03 (6.03) ¡0.66 (5.13) 5.78 (7.27) 5.57 (7.27) 5.35 (7.33) 5.01 (3.72) 4.91 (3.75) 4.79 (3.74) − 0.77 (5.76) − 0.66 (5.68) − 0.56 (5.65) 3.1.3. Relational and deal term concerns We asked participants to indicate how important different concerns were in their interaction with their counterpart (i.e., the provider of the product or of the service). Participants indicated the importance of relational concerns, rating three statements including, “I wanted to have a good relationship with the counterpart,” (Cronbach’s α = 0.883), and the importance of favorable deal terms (“I wanted to get the best deal for myself”), on a scale from 1: “Not at all” to 5: “Extremely”. We present the full list of items we used in Appendix B. Note. Ratings reflect how developing a good (compared to an OK) and a bad (compared to an OK) relationship with a negotiation counterpart would impact the economic outcome of the negotiation (from − 10: Much worse to +10: Much better). We define ERRO as the difference between these two ratings. ERRO is larger for service negotiations than for product negotiations. Participants ex­ pected good relationships and bad relationships to have a larger influence on the economic value for services than for products. We report average ratings and standard deviations in parentheses. 3.1.4. Negotiation behavior We asked participants if they had attempted to negotiate any terms of the deal (Yes/No) and who had initiated the discussion (themselves or their counterpart, since on the website, both would-be buyers and would-be sellers can post ads and message others). Participants completed the survey by answering demographic questions. the good relationship and bad relationship rating questions separately. Participants thought that a good relationship would be more beneficial for the value of services than for products (MServices = 5.29, SD = 2.90 vs. MProducts = 4.90, SD = 3.02; paired-t(967) = 4.85, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.156). Similarly, participants thought that a bad relationship would be more harmful for services than for products (MServices = − 0.93, SD = 5.41 vs. MProducts = − 0.66, SD = 5.13; paired-t(967) = 2.89, p = .004; Cohen’s d = 0.095). 3.2. Results 3. Study 1: High and low ERRO negotiations in an online marketplace 3.2.1. Relational and deal term concerns Buyers in high ERRO contexts, who purchased services, reported higher relational concerns (M = 3.51, SD = 0.98) than participants in low ERRO contexts, who bought products (M = 3.14, SD = 1.11; t(398) = 3.60, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.361). This result supports our prereg­ istered Hypothesis 1, and we depict these values in Fig. 3. Buyers’ concern for favorable deal terms was similar in the high ERRO (M = 3.86, SD = 1.00) and low ERRO contexts (M = 3.97, SD = 1.07; t(398) = − 1.06, p = .291; Cohen’s d = 0.106). We also note that buyers’ rela­ tional concern was lower than their deal term concern in both the high ERRO condition (t(205) = − 4.08, p < .001) and the low ERRO condition (t(193) = − 8.37, p < .001), as well as across conditions (t(399) = − 8.95, p < .001). In Study 1, we surveyed buyers who had reached agreements on Craigslist (craigslist.org), an online marketplace that facilitates millions of service and product exchanges between buyers and sellers each day (Kroft & Pope, 2014). In our survey, we assessed buyers’ relational and deal term concerns across high and low ERRO contexts. Building on our Pilot Study results, we operationalize high ERRO contexts as purchasing services, and low ERRO contexts as purchasing products. We preregis­ tered this distinction and our study at AsPredicted (https://aspredicted. org/blind.php?x=7rv3cqorg). 3.1. Method 3.2.2. Relational concerns and negotiation behavior In analyzing buyers’ negotiation behavior, we excluded 56 buyers who did not remember if they had initiated a negotiation (26 in low ERRO and 30 in high ERRO). Buyers were less likely to initiate a 3.1.1. Participants We surveyed 770 Craigslist users via MTurk (362 female; Mage = 36.74, SD = 10.92). We paid participants a flat payment of $1 for completing the survey, which took on average 8 min (SD = 5). We asked participants to describe their most recent transaction, and we found that 199 participants had sold products, 209 had purchased products, 156 had provided services, and 206 had purchased services. Consistent with our preregistration and conceptualization of ERRO, we focused on buyers – for whom we theorize their counterparts’ post-negotiation motivation may be particularly important. We report results for the 400 participants (186 female; Mage = 37.2, SD = 11.5) who purchased services or products and correctly completed attention checks. Including the 15 buyers who failed the attention check did not affect the direction or significance of our key findings. We report results for sellers, who provided services or products, in the Supplementary Online Materials. 3.1.2. Procedure We asked participants to recall their recent exchange through the Craigslist website, and to recall their concerns and experiences. We asked participants whether they had purchased a product through Craigslist, sold a product, purchased a service, and provided a service Fig. 3. Buyer’s relational and deal term concerns in high and low ERRO con­ texts (Study 1, N = 400). Note. Buyers are more concerned about their rela­ tionship with the provider in high ERRO contexts than they are in low ERRO contexts. Error bars represent ± S.E.M. 6 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 negotiation in high ERRO contexts (M = 76.8%, SD = 42.3) than in low ERRO contexts (M = 93.3%, SD = 25.0; logit regression B = − 1.440, 95% CI = [− 2.129, − 0.751]; z = − 4.10, p < .001). A Chi2 test on the binary initiation variable showed similar results (Chi2(1) = 18.816, p < .001). We next tested whether buyers’ relational concerns mediate the ef­ fect of ERRO on their propensity to initiate a negotiation (as a binary variable). We used the indirect bootstrapping technique to test for mediation using a logit regression, with 5000 resamples. We find a significant indirect effect of relational concerns on initiating negotiation (B = − 0.512, 95% CI = [− 0.860, − 0.164]). We also still find a signifi­ cant direct effect of ERRO, even controlling for this indirect effect (B = − 1.205, 95% CI = [− 2.004, − 0.607]). These results remain the same when we include participants’ deal term concern in the model; this variable does not have a significant impact on whether or not the buyer initiated a negotiation (B = 0.189, z = 1.10, p = .272). determined the sample size in advance to guarantee at least 80% power in detecting differences above d = 0.35. 4.1.2. Procedure Participants were buyers in a hypothetical exchange with a provider on Craigslist. In the high ERRO condition, we informed participants that they were looking for someone to clean their house; in the low ERRO condition, we informed participants that they were looking for a used vacuum. We asked participants to think about their future interaction with the provider (seller). Participants rated the importance of relational concern (α = 0.913) and concern for favorable deal terms (α = 0.896) on 5-point scales from 1: “Not at all” to 5: “Extremely”. We list the items in Appendix B. 4.1.2.1. Negotiation strategy. Participants chose negotiation strategies (“bots”) that reflected explicit trade-offs between relational and eco­ nomic concerns. First, participants chose among a set of five bots that reflect different mixes of negotiation strategies yielding an expected outcome indicated by: “4/7 profit; 0/7 relationship”, “3/7 profit; 1/7 relationship”, “2/7 profit; 2/7 relationship”, “1/7 profit; 3/7 relation­ ship”, or “0/7 profit; 4/7 relationship”. We included two lines of text to describe each bot’s strategic approach and the expected outcome (Ap­ pendix C). After participants made their first choice, they made a second stra­ tegic choice with a larger “budget.” In this second set of choices, the bots’ expected outcomes ranged from “7/7 profit, 0/7 relationship” to “0/7 profit, 7/7 relationship” in one-point intervals (we present the bots in Appendix C). Based on the two choices, we calculated the IncomeConsumption Curve (ICC) as the linear slope for each participant: The difference in relational points between the two choices divided by the difference in deal term points. This slope measures the change in in­ dividuals’ preferences between deal terms and relationships, reflected by the budget change. We can thus investigate the extent to which ne­ gotiators privilege relational concerns over obtaining favorable deal terms across high ERRO and low ERRO contexts. Finally, participants answered demographic questions. We prereg­ istered this study on AsPredicted (https://aspredicted.org/blind.php? x=rg8he3). 3.2.3. Participant gender Consistent with our preregistration for this study and the other studies in this paper, we conducted exploratory analyses that included participant gender and the interaction between gender and ERRO. Including gender did not affect any of our key findings in this study or any of our subsequent studies. 3.3. Discussion In an online marketplace, we find that buyers care more about their relationship with their counterpart in high ERRO than low ERRO con­ texts. This finding supports Hypothesis 1. We also find that buyers are significantly less likely to initiate a negotiation in high ERRO contexts than they are in low ERRO contexts, and that buyers’ concerns about their relationship with their negotiation counterpart mediate their willingness to negotiate. These findings provide initial support for our theory and conceptualization of ERRO. 4. Study 2: Explicit trade-offs between relational and deal term concerns In Study 2, we investigate how negotiators trade-off relational and deal term concerns. We develop a novel negotiation paradigm to capture explicit trade-offs by adapting the Income-Consumption Curve frame­ work from the economics literature (see Rutherford, 2013). Specifically, we describe negotiation “bots” that operationalize trade-offs between better deal terms and better relational outcomes. We impose a strict “budget,” such that better outcomes along one dimension are associated with worse outcomes along the other dimension. Consistent with Study 1, we operationalize high ERRO as service purchases, and low ERRO as product purchases. In this study, we randomly assign negotiators to be buyers in either high ERRO or low ERRO contexts to rule out selfselection concerns that might have influenced our findings in Study 1. In the Supplementary Online Materials we also report a robustness check study (Supplemental Study 2), in which we contrast high ERRO and low ERRO negotiations within service exchanges. 4.2. Results 4.2.1. Relational and deal term concerns Participants were more concerned about their relationship with their counterpart in the high ERRO condition than they were in the low ERRO condition (M = 3.16, SD = 0.99 versus M = 2.18, SD = 0.95; t(293) = 8.59, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 1.000). Conversely, participants were less concerned about reaching favorable deal terms in the high ERRO con­ dition (M = 4.11, SD = 0.73) than they were in the low ERRO condition (M = 4.49, SD = 0.63; t(293) = − 4.73, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.550). We depict this pattern in Fig. 4. 4.2.2. Negotiation strategy choices In the first strategic choice, participants distributed 4 points between relational and deal term concerns. In this first choice, participants allocated more points to relational concerns in the high ERRO condition (M = 1.73 out of 4, SD = 0.83) than they did in the low ERRO condition (M = 1.06, SD = 1.01; t(293) = 6.17, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.725). In the second strategic choice, participants allocated 7 points. Again, par­ ticipants allocated more points to relational than deal term concerns in the high ERRO condition (M = 2.62 out of 7, SD = 1.28) than they did in the low ERRO condition (M = 1.68, SD = 1.56; t(293) = 5.64, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.659). We depict these results, supporting Hypothesis 2, in Fig. 5. Importantly, from the two choices participants made, we can calculate the Income-Consumption Curve (ICC) as a linear slope for each 4.1. Method 4.1.1. Participants We recruited 302 MTurkers to participate in a short study in ex­ change for $1.00 (participants spent an average of 6 min in the survey; SD = 5). We report results from 295 participants who correctly answered the attention check (134 female; Mage = 37.5, SD = 10.3) and note that our results hold when we include all participants in the analyses. Participant gender did not affect the direction or significance of any of our key findings. We randomly assigned participants to one of two experimental conditions: High or low ERRO. Informed by results from Study 1, we 7 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 We note that the mediation findings hold when we include partici­ pants’ deal term concern in the mediation models: We find that deal term concern significantly affected both choices (Choice 1: B = 0.375, z = 4.35, p < .001; Choice 2: B = 0.479, z = 3.86, p < .001) and the slope (B = − 0.141, z = − 2.44, p = .015), but we still observe a significant indirect effect of relational concerns for all dependent variables (all p’s < 0.024). 4.3. Discussion In Study 2, we introduce a novel negotiation paradigm that requires participants to make explicit trade-offs between favorable deal terms and better relational outcomes. Across two rounds of decisions, we find that participants’ preferences for relational outcomes were significantly influenced by ERRO: Participants were more willing to forego better deal terms to obtain a better relational outcome in high, rather than low ERRO contexts. Consistent with Study 1, participants rated relational concerns as more important in high ERRO contexts than they did in low ERRO contexts, providing further support for Hypothesis 1. In addition, par­ ticipants rated deal terms as relatively less important in high ERRO negotiations. The impact of ERRO on negotiation strategies was partially mediated by negotiators’ relational concerns, providing support for Hypotheses 2 and 3. Taken together, these findings introduce a new negotiation paradigm to assess relative preferences, build confidence in the underlying ERRO construct, and bridge micro-economic research with the negotiation literature. Fig. 4. Relational and deal term concerns in high and low ERRO negotiations (Study 2, N = 295). Note. Participants are more concerned about relationships in high ERRO than low ERRO contexts, and relatively less concerned about favorable deal terms. Error bars represent ± S.E.M. 5. Study 3: Incentivized Bosses and Workers in high and low ERRO contexts In Studies 3a and 3b, we manipulate ERRO directly, rather than describe the negotiation contexts as a product or service. In Study 3a, we extend Study 2 and assess how ERRO impacts negotiators’ concerns and trade-offs in an incentive-compatible context. In Study 3b, we investi­ gate the downstream impact of negotiators’ use of competitive and collaborative negotiation strategies on their counterparts’ postnegotiation effort and ultimately on their economic outcomes. In addi­ tion, in this study we measure relational outcomes using the subjective value scale (SVI; Curhan et al., 2006). In this study, we assess the link between relational outcomes and economic outcomes to test Hypothesis 4. Taken together, in Studies 3a and 3b we investigate how ERRO in­ fluences negotiator behavior, relational outcomes, post-negotiation behavior, and economic outcomes. Fig. 5. Negotiation strategy choices: Trading off relationship and deal term gains when negotiating in high ERRO versus low ERRO contexts (Study 2, N = 295). Note. Participants allocate more points to improve relationships (versus deal terms) in the high ERRO condition than they do in the low ERRO condi­ tion. Dashed lines reflect the point budgets in each choice set. Lighter dots represent ± S.E.M. participant. The ICC is steeper – reflecting a larger preference for improving relational outcomes relative to deal terms – in the high ERRO (M = 0.56, SD = 0.77) than in the low ERRO condition (M = 0.35, SD = 0.72; t(293) = 2.36, p = .019; Cohen’s d = 0.274). Put differently, in the high ERRO condition, participants allocated about half of the additional budget to improving their relationship with their counterpart, compared to only a third of the additional budget to improving their relationship with their counterpart in the low ERRO condition. 5.1. Method For this study, we designed a novel negotiation task with a postnegotiation stage. First, the Boss and the Worker negotiate a salary. Then, after they reach an agreement, the Worker decides how much costly effort to exert on behalf of the Boss. We operationalize ERRO as the relative importance of the Worker’s effort in determining the Boss’ economic outcome. In Study 3a we investigate the Boss’ concerns and decisions; in Study 3b we investigate the Worker’s decisions and the downstream impacts of these decisions for the Boss. We describe the context as a “widget-selling task.” In this task, the Worker travels to sell widgets, and decides how many miles to travel, from 0 to 5 miles. The more the Worker travels, the more widgets they are likely to sell, but each mile of travel is costly for the Worker. In addition to the Worker’s travel (effort), luck plays a role in determining total sales. Luck is a random number between 0 and 5. The Boss has a budget from which they pay the Worker a salary for the widget-selling task, and the Boss gets to keep what they do not pay the Worker. After the negotiation, the Worker chooses an effort level, the luck number is revealed, and the Boss then earns a profit based upon the total number of sales. (The total sales reflect a combination of the Worker’s 4.2.3. Relational concerns and choices We next tested whether participants’ relational concerns mediated the impact of the ERRO condition on each of their two “bot” choices and the Income Consumption Curve slope. We used the indirect boot­ strapping technique to test for mediation, using 5000 resamples. We find a significant indirect effect of relational concerns on participants’ first choice (B = 0.194, 95% CI = [0.082, 0.306]), second choice (B = 0.417, 95% CI = [0.236; 0.598]), and the slope (B = 0.140, 95% CI = [0.053, 0.227]. For the two choices, the ERRO direct effect remained significant when we controlled for relational concerns (Choice 1: B = 0.476, 95% CI = [0.243; 0.709]; Choice 2: B = 0.532, 95% CI = [0.180, 0.884]). For the slope, relational concerns fully mediate the effect of ERRO (direct effect B = 0.048, p = .477). These findings are consistent with Hy­ pothesis 3. 8 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 effort level (miles traveled) and the Luck Number; the Worker does not directly profit from the total sales.) The Boss’ economic outcome is determined by the amount they pay the worker, the Worker’s effort, and luck. In the high ERRO condition, the Boss’ payment is determined mostly by the Worker’s effort; in the low ERRO condition, the Boss’ payment is determined mostly by luck. Specifically, in the high ERRO condition, the Worker’s effort has 9 times the impact of Luck on the total sales, whereas in the low ERRO condition, luck has 9 times the impact of the Worker’s effort on total sales. We include the full instructions and details for Studies 3a and 3b in Appendix D. 6.2.2. Negotiation strategy choices In the first negotiation strategy decision (distributing 4 points), participants allocated more points to relational concerns in the high ERRO round (M = 1.88 out of 4, SD = 1.02) than they did in the low ERRO round (M = 1.51, SD = 1.00; paired-t(178) = 4.48, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.336). In their second strategic choice (distributing 7 points), participants again allocated more points to relational concerns in the high ERRO round (M = 3.00 out of 7, SD = 1.65) than they did in the low ERRO round (M = 2.44, SD = 1.46; paired-t(178) = 4.99, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.359). As in Study 2, we calculated the Income-Consumption Curve (ICC) as a linear slope for each participant per round (i.e., slopes for the high- and low ERRO rounds). Consistent with our findings in Study 2, the ICC slope was steeper (reflecting an increasing preference for relational outcomes) in the high ERRO round (M = 0.80, SD = 0.82) than in the low ERRO round (M = 0.59, SD = 0.73; paired-t(178) = 3.32, p = .001; Cohen’s d = 0.270). These slopes can be interpreted as follows: In the high ERRO round, participants allocated about 4/5 of the additional budget to relational outcomes (rather than deal term gains), whereas in the low ERRO round participants allocated about 3/5 of the additional budget to relational outcomes. We depict these data, supporting Hypothesis 2, in Fig. 6. 6. Study 3a: Costly trade-offs 6.1. Method 6.1.1. Participants We recruited 218 participants from a University Behavioral Lab pool. Consistent with our preregistration (https://aspredicted.org/blind.php? x=py9qq6), we analyzed the data of 179 participants who correctly answered the attention check (131 female; Mage = 21.6, SD = 4.9). Including all participants in the analyses did not affect the direction or significance of our key findings, nor did participant gender. Participants received Amazon gift cards that included a base participation payment of $3.00 and a bonus payment that depended on their decisions in the experiment (M = $2.99, SD = $0.88). Participants spent an average of 14 min in the study (SD = 12). Our design included two within-participant conditions (high vs. low ERRO), and we deter­ mined the sample size in advance to guarantee at least 80% power in detecting within-participant effect sizes above 0.20.4 6.2.3. Relational concern and choices We tested if participants’ relational concern mediate the impact of ERRO on their choices. We again used the indirect bootstrapping tech­ nique to test for mediation, using 5000 resamples. We find an indirect effect of relational concerns for participants’ first choice (B = 0.534, 95% CI = [0.428, 0.640]), second choice (B = 0.786, 95% CI = [0.610, 0.963]), as well as on the ICC slope (B = 0.259, 95% CI = [0.177, 0.340]), providing some support for Hypothesis 3. Notably, the ERRO direct effect remained significant in all of these analyses, even when controlling for relational concerns (all direct effect p’s < 0.006). As in Study 2, deal term concern significantly affected both choices (Choice 1: B = 0.241, z = 3.08, p = .002; Choice 2: B = 0.416, z = 3.59, p < .001) and the slope (B = − 0.122, z = − 2.36, p = .018). Importantly, our key results remain unchanged. That is, we still observe a significant indirect effect of relational concerns for all DVs (p’s < 0.001). 6.1.2. Procedure We informed participants that they would be the “Boss” in this experiment and that they would be matched with another participant who is the “Worker.” In actuality, we assigned all participants in this study to the role of the Boss. Each Boss participant answered questions for both the low ERRO condition (total sales are mostly determined mostly by luck) and the high ERRO condition (total sales are mostly determined by the Worker’s effort (miles)). In both the high ERRO and low ERRO rounds, participants read the instructions and answered comprehension questions. As in our prior studies, in each round, par­ ticipants rated the importance of relational concerns and favorable deal terms (Appendix B). Next, in each of the two ERRO conditions, participants made two strategy decisions as in Study 2 (“Negotiation Bots”; Appendix C). The first choice was always among 5 bots, and the second choice was among 8 bots. In total, participants made 4 decisions: We analyzed all of the dependent variables within-participants. Finally, participants answered demographic questions. 7. Study 3b: ERRO and workers’ post-negotiation behavior In this study, we explore how negotiator behavior impacts post- 6.2. Results 6.2.1. Relational and deal term concerns As in our prior studies, participants were more concerned about their relationship with their worker-counterpart in the high ERRO condition (M = 3.59, SD = 0.99) than they were in the low ERRO condition (M = 3.39, SD = 0.97; paired-t(178) = 2.76, p = .006, Cohen’s d = 0.204), supporting Hypothesis 1. Participants were equally concerned about reaching favorable deal terms across conditions (MhighERRO = 3.35, SD = 0.78 vs. MlowERRO = 3.42, SD = 0.78; paired-t(178) = − 1.48, p = .141; Cohen’s d = 0.090). Fig. 6. Negotiation strategy choices: Trading off relationship and deal term gains when negotiating in high ERRO versus low ERRO contexts (Study 3a, N = 179). Note. Participants allocated more points to improve relationships (at the expense of favorable deal terms) in the high ERRO condition than in the low ERRO condition. Dashed lines reflect the point budgets in each choice set. Lighter dots represent ± S.E.M. 4 We wanted to have sufficient power to test exploratory hypotheses withinand between-participants, hence the larger sample size relative to Study 2. 9 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 negotiation effort and economic outcomes. We use the same context as the one we used in Study 3a, and we expect the benefits to a Boss of choosing a collaborative, rather than a competitive, strategy to be higher in the high ERRO context (because high Worker effort matters a great deal) than in a low ERRO context (because high Worker effort matters relatively less). We test Hypothesis 4, that there is a stronger relation­ ship between relational outcomes and economic outcomes in the high ERRO context compared to the low ERRO context. 7.2. Results 7.2.1. Workers’ post-negotiation effort We regressed Workers’ effort on ERRO condition, Boss’ strategy, and their interaction term, with the model variance clustered by participant to account for multiple decisions. Across the two Boss’ strategy condi­ tions, Workers chose directionally, but not significantly, higher effort levels (miles) in the high ERRO condition (M = 2.46, SD = 1.66) than they did in the low ERRO condition (M = 2.25, SD = 1.58; B = 0.214, t (222) = 1.28, p = .201). Notably, we find a significant interaction effect (BERRO×Collaborative = 0.186, t(222) = 2.03, p = .044): In line with our theorizing, the economic impact of the Boss’ negotiation strategy was larger in the high ERRO condition (B = 1.714, t(110) = 13.13, p < .001) than it was in the low ERRO condition (B = 1.342, t(112) = 10.35, p < .001). Consistent with our theorizing, we also find this interaction effect on Bosses’ expected earnings (BERRO×Collaborative = 5.311, t(222) = 5.03, p < .001). 7.1. Method 7.1.1. Participants We recruited 313 participants from a University Behavioral Lab pool, and we analyzed the data of 226 who correctly completed the attention check (160 female; Mage = 22.9, SD = 7.9). Including all participants in the analyses did not affect the direction or significance of our key findings, nor did participant gender affect any of our key findings. As in Study 3a, participants received Amazon gift cards that included a base participation payment of $3.00 and a bonus that depended on their decisions in the experiment (M = $1.34, SD = $0.15). Participants spent an average of 11 min in the study (SD = 19). We had two withinparticipant conditions, and we determined the sample size to be able to detect effect sizes of approximately 0.30 between-participants with 80% power.5 Participants who completed Study 3a could not participate in this study. 7.2.1.1. Relational outcomes and economic outcomes. We first examined Workers’ relationship satisfaction by regressing satisfaction on the ERRO condition, Boss’ strategy, and their interaction term, with the model variance clustered by participant. As expected, Workers had higher relational outcomes with collaborative Bosses (M = 5.04, SD = 1.15) than competitive Bosses (M = 1.81, SD = 0.90; B = 3.231, t(222) = 34.46, p < .001). Although we expected the ERRO × Boss’ strategy interaction to be significant, neither the interaction term nor the main effect of ERRO were significant predictors (both p’s > 0.41). Hypothesis 4 predicts that ERRO will moderate the relationship be­ tween Workers’ relational outcomes and their effort choices. As we re­ ported above, ERRO did interact with the Boss’ strategy to affect effort. Next, we tested whether relational outcomes mediated this relationship. We thus regressed effort choices on relationship satisfaction, the Boss’ strategy, ERRO condition, and the ERRO × Boss’ strategy interaction term, clustering the variance by participant. We used the indirect bootstrapping technique to test for mediation of the ERRO × Boss’ strategy interaction by relationship satisfaction, using 5000 resamples and find evidence for mediation on Workers’ effort (BRelationship = 0.448; 95% CI = [0.326, 0.569]; the interaction between ERRO and the Boss’ strategy was no longer significant - direct effect p = .090).6 We also note that the effect of relational outcome remains similar when we included all four SVI dimensions; in this analysis, we also see a significant effect of the instrumental outcome (B = 0.238, t(218) = 3.23, p = .001). Next, we conducted a similar mediation model on the Bosses’ ex­ pected earnings by the Boss’ strategy, ERRO condition, and the ERRO × Boss’ strategy interaction term with Workers’ relationship satisfaction as the potential mediator, clustering the variance by participant. We find both an indirect effect through relationship satisfaction (BRelationship = 2.337; 95% CI = [1.017, 3.658]) and a direct effect of the ERRO × Boss’ strategy interaction term (BERRO×Strategy = 5.172, 95% CI = [3.083, 7.262]). We depict this interaction effect in Fig. 7. 7.1.2. Procedure Participants completed the study online, and we used a similar procedure to the one we used in Study 3a. In this study, however, all participants were “Workers.” We randomly assigned Workers to either the high ERRO or the low ERRO condition. We had two withinparticipant conditions pertaining to the Boss’ strategy (for ease of reference, Competitive or Collaborative). We told participants that in each of two rounds they would be matched with a “Boss” participant: a different Boss in each round. We described the Boss’ behavior in the negotiation using the descriptions below (similar to the descriptions of the two extreme negotiation bots we used in Studies 2 and 3a): Collaborative: “In this negotiation, the Boss sent very collaborative messages. The Boss considered your perspective, asked questions, and made concessions. The Boss was very focused on developing a good relationship with you, not on just getting the best deal terms for themselves.” Competitive: “In this negotiation, the Boss sent very aggressive mes­ sages. The Boss often interrupted you, threatened to leave, and made really low offers. The Boss was very focused on getting the best deal terms for themselves, not on developing a good relationship with you.” In both rounds, participants read that they negotiated with the Boss and agreed to a salary of 300 points, and read the negotiation descrip­ tion (Competitive or Collaborative). Participants then chose their effort level – the number of miles of travel (from 0 to 5). Next, they answered items from the Subjective Value Inventory (Curhan et al., 2006); we focus on the relationship satisfaction dimension (α = 0.985) and present the full scales we used in Appendix B and the main instruction text in Appendix D. Finally, participants answered demographic questions. We prereg­ istered this study on AsPredicted (https://aspredicted.org/blind.php? x=52pz4x). 7.3. Discussion In Study 3, we manipulate ERRO and introduce a novel, incentive6 As we pre-registered, we also included a relationship conflict measure (Hart & Schweitzer, 2020). This measure was highly correlated with the subjective relationship satisfaction measure (R = − 0.872, p < .001). For brevity, we now focus on the relationship satisfaction measure, and note that the result patterns are similar for the conflict measure: Workers perceived higher conflict with the competitive bosses than with the collaborative bosses (M = 4.00, SD = 0.66 vs M = 2.27, SD = 0.72; B = 1.803, t(2 2 2) = 27.15, p < .001), and perceived conflict mediated the interaction effect between ERRO and Boss’ strategy on Workers’ effort (B = − 0.780; 95% CI = [− 0.954, − 0.606]; direct effect p > .26). 5 This sample size allows us to detect effect sizes d > 0.20 within-participants with 80% power; as in Study 3a, we wanted to have sufficient power to test our exploratory between-participants hypotheses. 10 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 8. Study 4: Interactive boss-worker negotiation In Study 4, we extend our investigation of ERRO in a dyadic nego­ tiation that includes a post-negotiation stage in which negotiators’ effort can influence their counterparts’ economic outcomes. We manipulate ERRO across dyads to explore how ERRO influences negotiator in­ tentions, negotiator behavior, relational outcomes, post-negotiation behavior, and economic outcomes. 8.1. Method 8.1.1. Participants We recruited 353 participants from a university Behavioral Lab pool,7 and consistent with our preregistration https://aspredicted. org/blind.php?x=nr5gi3, we analyzed the data of 279 participants who correctly completed the attention check (222 female; Mage = 23.9, SD = 8.0); including all participants in the analyses did not affect the direction or significance of our key findings. Participant gender also did not affect any of our key findings. Participants received Amazon gift cards that included a base participation payment of $4.00 and a bonus payment that depended on participants’ decisions (M = $1.78, SD = $0.95). Participants spent an average of 12 min in the study (SD = 7). Fig. 7. Bosses’ expected economic outcomes (earnings) by Workers’ relation­ ship satisfaction in high and low ERRO conditions (Study 3b, N = 226). Note. The economic outcomes Bosses would have earned are more positively related with Workers’ relationship satisfaction (SVI relational aspect) in the high ERRO condition than they are in the low ERRO condition. Lines represent linear regression line; bands represent 95% CI. compatible negotiation paradigm that includes a post-negotiation stage. As in our prior studies, negotiators in Study 3a were more likely to privilege relational concerns over deal term concerns when ERRO was high than when ERRO was low. In Study 3b, we examine the downstream impact of privileging collaborative versus competitive negotiation tactics in high and low ERRO contexts. As predicted, we find interaction effects between ERRO and the Bosses’ negotiation strategy on both Workers’ relational out­ comes and their post-negotiation effort. Workers invested greater postnegotiation effort for Bosses who chose collaborative tactics than they did for Bosses who chose competitive tactics. Greater effort benefited Bosses in both high and low ERRO contexts, but it particularly benefited Bosses in high ERRO contexts. These results provide support for Hy­ pothesis 4: In high ERRO contexts, relational outcomes are more strongly linked with economic outcomes than they are in low ERRO contexts. In this study, we manipulated whether the context was high or low ERRO for the Boss, and Bosses acted differently across the two ERRO conditions. Bosses chose more collaborative tactics in the high ERRO condition than they did in the low ERRO condition, and the more collaborative Bosses were, the harder Workers worked. We did not, however, find a main effect of ERRO on Workers’ relational outcomes or effort. Workers’ relational outcomes and effort are downstream effects of the Bosses’ ERRO condition, and we speculate that our experimental paradigm may have limited the influence of Bosses’ strategic choices on Workers’ perceptions and behavior. In contexts that allow greater communication and richer opportunities to build rapport, we would expect to observe stronger effects of ERRO on a negotiation counterpart. Taken together, these findings link the use of competitive negotiation strategies with relational outcomes, post-negotiation effort, and eco­ nomic outcomes. By incorporating ERRO into the negotiation frame­ work, we identify when attending to relational concerns is more important (when ERRO is high) or less important (when ERRO is low). Studies 3a and 3b show the impact of ERRO on negotiators’ concerns, behavior, and post-negotiation outcomes in a novel, work-relevant setting in which ERRO is manipulated in a within-participant design. One potential limitation of these studies is that the designs may have led participants to focus on the differences between these contexts more then they might in a between-participant design. In Study 4, we address this potential limitation in a between-participant design. We use a dyadic, interactive negotiation paradigm in which participant-dyads are assigned to one ERRO condition and negotiate via an online chat platform. 8.1.2. Procedure We randomly assigned participants to the “Boss” or the “Worker” roles and paired them for a joint task. In the first stage of the study, the Boss and the Worker negotiated a salary, a distributive issue for which each could receive between 0 and 1000 points. Dyads negotiated in an online, interactive chat platform. In the second stage of the study, the Workers completed an effortful, “online item-moving” task that involved repeatedly clicking on an item and dragging it across the screen. Workers could move as many or as few items as they wished from 0 to 100 (Hart & Schweitzer, 2020). All participants completed a sample of the task before the negotiation. As in Study 3, we operationalized ERRO as the importance of the Worker’s effort in determining the Boss’ post-negotiation outcome. In addition to earning points from the salary negotiation (0–1000 points), the Boss could earn points after the negotiation concluded: In the high ERRO condition, the Boss’ post-negotiation outcome depended on how many items the Worker completed (0–100 items, multiplied by 10 points); in the low ERRO condition, the Boss’ post-negotiation outcome depended only on a random luck number (0–100, multiplied by 10 points). In both conditions, the Worker’s economic outcome depended only on the negotiated salary. After reading the instructions, participants rated the importance of relational concerns and favorable deal terms using the same scales we used in our prior studies (see Appendix B). Participants then indicated how they intend to behave in the negotiation, from 0: “Completely collaborative” to 10: “Completely assertive.” We include the exact in­ structions we used in Appendix E. Next, Boss—Worker dyads interacted through a real-time comput­ erized chat platform (Molnar, 2019) for up to five minutes of uncon­ strained chat. To remind participants of the payoffs, we presented the payment scheme above the chat window. After participants completed the chat stage, they answered questions about their subjective value of the negotiation (SVI; Curhan et al., 2006). Worker participants then completed the item-moving task: They had up to 4 min to move as many items as they wished and could quit the task at any time. Following the experiment, we recruited three research assistants to code the text of each negotiation. The research assistants, blind to 7 We preregistered our plan to collect responses from approximately 400 participants by posting the study for a single university-lab study session. We determined this sample size based on our effect sizes in prior studies. 11 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 condition and hypotheses, coded each of the negotiations for focus on the relationship, focus on the deal terms, and conflict in the negotiation. They rated each dimension on a 5-point scale from 1: “Not at all” to 5: “Extremely.” We averaged the three raters’ scores (inter-rater agreement α values were 0.658, 0.856, and 0.883 for the three measures). post-negotiation effort. On average, Workers completed 48.7 items (SD = 43.4). We regressed the quantity of work Workers completed on their relationship satisfaction with their Boss counterpart, the ERRO condi­ tion, and the interaction term. The better the relationship Bosses developed with their Worker counterparts, the more work the Worker completed (B = 26.834, t(131) = 8.97, p < .001). We note that the coefficients for ERRO and the interaction were not significant (p’s > 0.22). However, the relationship effect on Workers’ effort was larger in the high ERRO condition (B = 30.471, t(65) = 8.33, p < .001) than in the low ERRO condition (B = 23.197, t(66) = 4.83, p < .001). 8.2. Results Consistent with our preregistration, our main analyses focus on Boss participants’ concerns, behavior, and post-negotiation outcomes. We also report results for Workers’ effort and their subjective, relational outcomes. 8.2.6. Bosses’ economic outcomes We compared the relationship effect on Bosses’ economic outcomes in the high ERRO and low ERRO conditions. We find a significant interaction effect between ERRO and Workers’ relationship satisfaction (B = 379.092, t(120) = 5.23, p < .001). In Fig. 8 we depict these results for the high and low ERRO conditions, providing support for Hypothesis 4. To better understand this interaction, we next report separate analysis for each ERRO condition. We also note that the Workers’ relationship satisfaction also had a main effect, across conditions (B = 202.564, t (124) = 5.59, p < .001). In the high ERRO condition, Bosses’ outcomes depended on two factors: the salary they agree to pay the Worker and the amount of work the Worker completes. We regressed Bosses’ economic outcomes in the high ERRO condition on their Worker counterparts’ relationship satis­ faction. Supporting our theory, we find that Bosses in the high ERRO who developed better relationships with their Worker counterparts earned better economic outcomes (B = 392.110, t(67) = 8.03, p < .001). In the low ERRO condition, again consistent with our theory, we did not find an effect of relationship satisfaction on Bosses’ economic out­ comes (B = 13.018, t(57) = 0.24, p = .809). 8.2.1. Relational and deal term concerns As in our prior studies, Bosses rated their concern for their rela­ tionship with their counterpart higher in the high ERRO condition (M = 3.49, SD = 1.03) than they did in the low ERRO condition (M = 2.90, SD = 0.98; t(142) = 3.52, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.587), supporting Hy­ pothesis 1. Bosses were similarly concerned about attaining a favorable salary across conditions (MhighERRO = 3.77, SD = 0.88 vs. MlowERRO = 3.89, SD = 0.72; t(142) = − 0.90, p = .371; Cohen’s d = 0.149). 8.2.2. Negotiation strategy Before negotiating, Bosses in the high ERRO condition intended to be directionally more collaborative (versus assertive) (M = 5.40, SD = 2.06) than did Bosses in the low ERRO condition (M = 4.81, SD = 2.08; t (142) = 1.71, p = .090; Cohen’s d = 0.285). Consistent with our pre­ registration, although the main effect was only marginally significant, we conducted a mediation model: Bosses’ relational concerns mediate the relationship between ERRO on Bosses’ negotiation intended strat­ egy. We conducted indirect bootstrapping with 5000 resamples (B = 0.963; 95% CI = [0.659, 1.266, 0.659]; direct effect B = 0.021, p = .946). These finding are consistent with Hypotheses 2 and 3. We next included Bosses’ deal term concern in the model predicting negotiation strategy: The deal term concern had a significant effect on the intended strategy (B = − 0.672, t(140) = 3.66, p < .001), but the mediating effect of relational concern remained (p < .001). 8.3. Discussion In this study, we used an interactive negotiation to explore how ERRO influences ex-ante relational concerns, the negotiation process itself, and negotiated outcomes including deal terms, relational out­ comes, and post-negotiation effort. We find that compared to Bosses in the low ERRO condition, Bosses in the high ERRO condition cared more about developing a positive relationship with their counterpart and negotiated more collaboratively. We also find that Bosses in the high ERRO condition who developed better relationships with their coun­ terparts earned better economic outcomes than did those who did not, because their counterparts completed more work following the 8.2.3. Negotiation process To gain further understanding of how collaborative Bosses were, we conducted exploratory analyses of the content of the negotiations themselves. We did not preregister the text coding or negotiation process analyses that we conducted, but these exploratory analyses enable us to gain insight into how Bosses acted across the ERRO conditions. As coded by independent raters who were blind to condition, Bosses in the high ERRO condition were significantly more relationship-focused (MHigh­ ERRO = 1.91, SD = 0.91 vs. MLowERRO = 1.49, SD = 0.69; t(130) = 2.98, p = .003), less deal term (salary) focused (MHighERRO = 3.29, SD = 1.15 vs. MLowERRO = 4.50, SD = 0.65; t(130) = − 7.75, p < .001), and less conflictual (MHighERRO = 2.17, SD = 1.10 vs. MLowERRO = 2.65, SD = 1.07; t(130) = − 2.50, p = .014) than were Bosses in the low ERRO condition. 8.2.4. Relational outcomes Overall, Workers rated their relationship with their Boss counterpart as similar (though directionally higher) in the high ERRO condition than in the low ERRO condition (MhighERRO = 4.04, SD = 2.12 vs. MlowERRO = 3.57, SD = 1.82; t(133) = 1.38, p = .168; Cohen’s d = 0.238). We next regressed Workers’ relational outcomes on ERRO and the Bosses’ intended strategy: More assertive strategies somewhat diminished Workers’ relationship satisfaction (B = − 0.155, t(132) = − 1.95, p = .053); the effect of ERRO was not significant (B = 0.460, t(132) = 1.36, p = .175). Fig. 8. Bosses’ economic outcomes by Workers’ relationship satisfaction in high and low ERRO conditions (Study 4, Bosses N = 140). Note. The total economic outcomes Bosses earned are positively associated with Workers’ relationship satisfaction (SVI relational aspect) in the high ERRO condition but not in the low ERRO condition. Lines represent linear regression line; bands represent 95% CI. 8.2.5. Post-negotiation effort We next explored the links among ERRO, relational outcomes, and 12 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 their overall, final economic outcomes; in low objective ERRO contexts, relational outcomes are only weakly related to economic outcomes. Negotiators, however, may misperceive ERRO. In some cases, negotia­ tors may perceive the context to have greater ERRO than it does, and in others far less than it does. We assert that perceptions of ERRO drive important cognitions and behavior. Specifically, perceived ERRO is likely to impact negotiators’ relational concerns and negotiation behavior (Fig. 1), whereas objective ERRO accounts for when differences in rela­ tional outcomes impact economic outcomes (Fig. 2). Our theorizing and findings also challenge the assumption that ne­ gotiators’ relational concerns and economic concerns are “dimensions [which] are regarded as independent” (Carnevale & Pruitt, 1992, p. 539). We identify ERRO as a contextual factor that determines the relative importance and relationship between negotiators’ deal term concern and relational concern. Second, by establishing the relationships among ERRO, negotiator behavior, and economic outcomes, we qualify the substantial negotia­ tion literature that describes how negotiation strategies (e.g., expressing anger, conceding slowly, or compromising) influence negotiated out­ comes. Prior work has made broad claims about the influence of nego­ tiation strategies on economic outcomes by failing to account for how post-negotiation behavior and negotiation context are likely to moder­ ate these relationships. By considering post-negotiation behavior, we explain how deal terms are not equivalent to economic outcomes. For example, aggressive negotiation tactics may enable negotiators to secure favorable deal terms. By accounting for ERRO, our findings reveal when these tactics are likely to improve economic outcomes and when they are likely to harm economic outcomes. Our work challenges a common assumption in negotiation research, that negotiators need to “forfeit joint economic outcomes […] in deference to the pursuit of relational goals and/or the adherence to relational norms” (Curhan et al., 2008, p. 193). Rather than reflecting a compensatory relationship, we show that in high ERRO settings collabo­ rative tactics may help both relational and economic outcomes, whereas assertive tactics may harm both relational and economic outcomes. Our theorizing solves an important puzzle in the negotiation literature. We explain why relational concerns are negatively related to economic outcomes in some cases (Amanatullah et al., 2008; Beest et al., 2008; Bowles et al., 2007), but positively related to economic outcomes in others (e.g., Curhan et al., 2010; Kong et al., 2014; Morris et al., 2002). We underscore the inherent and critical links among negotiation context, negotiators’ relational outcomes, and their economic outcomes. Third, related to our second contribution, our investigation un­ derscores the importance of accounting for post-negotiation behavior. We advance our understanding of the link between behavior within a negotiation (e.g., competitive or collaborative) and negotiator behavior after the negotiation (e.g., implementing an agreement). In contrast to prior theoretical and experimental negotiation research that has implicitly and explicitly assumed that negotiated deal terms represent the economic value of the negotiation (e.g., Amanatullah et al., 2008; Gelfand et al., 2006; Malhotra & Bazerman, 2008; O’Connor & Arnold, 2001; for exceptions, see: Campagna et al., 2016; Friedman et al., 2020; Hart & Schweitzer, 2020), we demonstrate when and how postnegotiation behavior can profoundly impact the economic value of the negotiation process. In addition to these theoretical contributions, our work informs several substantial practical implications. Many services are character­ ized by high ERRO, and our findings are particularly relevant for the service sector of the economy. More than two-thirds of the world’s Gross Domestic Product involves services (Soubbotina, 2004), and in devel­ oped nations, such as the United States, the service sector accounts for more than four-fifths of the economy. In contrast to the classic negoti­ ation paradigms that disproportionately reflect product-based negotia­ tion and have largely overlooked what happens after negotiators reach an agreement, our paradigms and findings offer a foundation for future work to expand our investigation of negotiation for services. negotiation. We did not find a main effect of ERRO on Workers’ relational out­ comes or their post-negotiation effort. However, we did observe the expected interaction effect between ERRO and negotiation behavior (specifically, conflict behavior) on Workers’ and Bosses’ outcomes. With a richer negotiation context and a larger sample, we expect these re­ lationships among ERRO, negotiation behavior, and Workers’ postnegotiation effort to be even stronger. 9. General discussion In this article, we introduce ERRO (the Economic Relevance of Relational Outcomes) as a fundamental dimension which characterizes negotiation contexts for each negotiator. In high ERRO contexts (e.g., hiring an employee), a substantial portion of the economic value of a negotiation is delivered after an agreement has been reached, when negotiators engage in post-agreement behavior that impacts their counterparts’ economic outcome. For example, if a boss negotiates aggressively with a new employee, the boss might obtain favorable contract terms but harm the employee’s post-negotiation motivation which, in turn, diminishes the boss’ economic value from the negotia­ tion. Notably, prior negotiation scholarship has overwhelmingly assumed that the deal terms negotiators agree to represent the economic value of a negotiation. A growing literature has considered relational outcomes in addition to deal terms (Amanatullah et al., 2008; Curhan et al., 2006; Gelfand et al., 2006; Gunia et al., 2011), but this work has treated relational and economic outcomes as separate dimensions of negotiators’ outcomes, and no prior work has explained when relational outcomes might be more or less likely to impact a negotiator’s economic outcomes. By introducing ERRO, we underscore the importance of postnegotiation behavior, even when the counterparts have no plans to engage in a future negotiation. That is, ERRO characterizes a single negotiation interaction. Importantly, by introducing ERRO, this article is also the first to explain when relational outcomes are more or less likely to impact economic outcomes: In high ERRO contexts, relational out­ comes are strongly linked with economic outcomes. In low ERRO con­ texts, relational outcomes are weakly linked with negotiators’ economic outcomes. Across four experiments (N = 1601), we document substantial dif­ ferences in negotiators’ strategic concerns and negotiation behavior in high ERRO and low ERRO contexts. Across our studies, compared to participants in low ERRO contexts, participants in high ERRO contexts expressed greater concern for relational outcomes and chose more collaborative negotiation strategies. In Studies 3 and 4, we show that privileging relational concerns and developing rapport with a counter­ part in high ERRO contexts can increase a counterpart’s post-negotiation effort and as a result yield better economic outcomes for the negotiator. 9.1. Implications and contributions Our findings have broad theoretical implications. First, our work identifies a novel and fundamental characteristic of negotiation con­ texts. In contrast to prior research that has overlooked differences in negotiation contexts and used similar payoff matrices (e.g., a three-issue integrative negotiation paradigm) interchangeably across negotiation domains, we demonstrate that negotiation contexts can and should be distinguished with respect to the dimension of the economic importance of relational outcomes. We offer a novel conceptual distinction based on ERRO. No prior work has done this, even though this distinction is essential to understanding the relationships among negotiator concerns (i.e., privileging relational over deal term concerns), negotiator behavior (i.e., privileging collaborative versus competitive tactics), the fundamental decision of whether or not to negotiate, and postnegotiation behavior. We distinguish objective ERRO from perceived ERRO. In high objective ERRO contexts, negotiators’ relational outcomes influence 13 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 In service and employment negotiations, contracts are often incom­ plete. As a result, we might expect service contracts to require greater clarification. Interestingly, in our studies, we found that rather than focusing more attention on deal term concern, negotiators in high ERRO contexts actually devoted less attention to deal term concern and instead focused on building rapport. Future work should explore when rela­ tional outcomes can substitute for detailed contracts. This idea is related to scholarship on contingent contracts that can help negotiators contend with uncertainty (Murnighan & Malhotra, 2002; Williamson, 1996). In most service and employment contexts, however, it is extremely difficult to anticipate the full range of eventualities (Holmstrom & Milgrom, 1991). As a result, negotiators agree on contracts that have implicit or unspecified terms (Rousseau, 1989; Simon, 1991). In these cases, parties are well served when they develop trust. Paradoxically, prior work has found that highly specified contracts can undermine trust (Malhotra & Murnighan, 2002; Weber et al., 2004). Our findings reveal that in high ERRO contexts, negotiators are well served by developing rapport. We call for future work to extend our findings to explore the relationships among collaborative negotiation behavior, contracts, rapport, and post-negotiation behavior. 2004; Bowles et al., 2007; Hart & Schweitzer, 2020), and our Study 1 suggests that negotiators in high ERRO contexts are not only more likely to collaborate with and accommodate their counterpart, but they may also be more likely to avoid initiating a negotiation altogether. In high ERRO contexts this may be rational. Surprisingly little prior work has explored reasons to avoid negotiations (see Kang et al., 2020 for an exception), and we call for future work to explore a negotiator’s decision not to negotiate. We further assert that advice to “ask for it” and “lean in” (Amanatullah & Tinsley, 2013; Bowles et al., 2007) should account for ERRO in the negotiation context. Quite likely, advice that is wellsuited to obtaining more favorable deal terms and better economic outcomes in some domains (e.g., low ERRO) may harm economic out­ comes in other domains (e.g., high ERRO). We call for future work to explore the moderating role of ERRO in guiding prescriptive negotiation advice. Broadly, we assert that the standard experimental paradigm in negotiation that concludes with a term sheet has limited our under­ standing of negotiation contexts and how relational outcomes impact economic value. We urge future negotiation scholars to focus on nego­ tiation context, how individuals negotiate, and post-negotiation behavior. 9.2. Limitations and future directions 10. Conclusion Our investigation contrasted high and low ERRO contexts. Though we studied ERRO as a dichotomy, we conceptualize ERRO as a contin­ uum. In general, we expect buyers’ negotiations for services to have higher ERRO than their negotiations for products, but many situational factors are likely to influence the extent to which a service or product exchange has high ERRO. For example, a product that involves delivery of the item and follow-up service (e.g., assembly) increases ERRO. We call for future work to explore ERRO across different negotiation do­ mains and contexts. In our studies, we found that negotiators readily perceived differ­ ences in ERRO across contexts, but future work should explore indi­ vidual differences in perceptions of ERRO. One difference that may influence perceptions of ERRO is culture. For example, different cultures have diverging views on the “fluidity” of negotiated agreements, the extent to which negotiated agreements can be changed over time (Friedman et al., 2020). Quite possibly, negotiators who perceive agreements to be more fluid are also more likely to think of them as higher ERRO. Future work could also investigate the relationship be­ tween ERRO and interdependent, relational construals. We suspect that individuals who construe a relationship as highly interdependent will be more likely to perceive their context as high ERRO. This relationship may account for potential gender differences in perceptions of ERRO. For example, across contexts, women negotiators may perceive higher ERRO than men. It is also possible that cultural expectations and other features of the negotiation process, such as alcohol consumption and where negotiations transpire (Schweitzer & Gomberg, 2001; Schweitzer & Kerr, 2000) could influence negotiators’ perception of ERRO. Taken together, perceived ERRO may be determined by both structural and psychological factors that cause negotiators to become more or less likely to focus on relational concerns. We call for future scholarship to explore how characteristics such as gender, culture, and relational selfconstrual impact subjective perceptions of ERRO. There could also be an interplay between expertise and ERRO. For example, some expert ne­ gotiators, seeking to obtain more favorable deal terms, may convince their counterparts that ERRO is more important than it is. We call for future work to investigate negotiators’ perceptions and misperceptions of ERRO across negotiation contexts. We also call for future work to explore the relationships among negotiator behavior, outcomes, and ERRO. This work should help us understand when and which assertive and collaborative negotiation strategies are most likely to improve economic outcomes. We also call for future work to explore the decision to initiate a negotiation. Initi­ ating a negotiation can harm relational outcomes (Babcock & Laschever, We introduce the Economic Relevance of Relational Outcomes (ERRO) as a fundamental dimension of negotiation contexts, which reflects the extent to which a negotiator’s relational outcomes can impact their counterpart’s post-negotiation behavior in a way that ultimately impacts the negotiator’s own final economic outcome. Supporting this concep­ tualization, we find that compared to negotiators in low ERRO contexts, negotiators in high ERRO contexts are more likely to privilege relational concerns over deal terms, and that relational outcomes exert more in­ fluence on economic outcomes in high ERRO than in low ERRO contexts. Our theorizing and findings fill a critical gap in the negotiation literature that has been overlooked by prior scholarship. We identify a key feature of the negotiation context that determines how, when, and why relational outcomes influence negotiators’ final economic out­ comes. What happens after negotiators reach an agreement can pro­ foundly influence economic outcomes, especially for negotiations involving services. ERRO determines when negotiators should privilege relational concerns over deal terms as they decide if and how to negotiate. CRediT authorship contribution statement Einav Hart: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Maurice E. Schweitzer: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Declaration of Competing Interest The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank the Wharton Behavioral Lab and the NTRPeterson Research Grant (2018) for financial support. The authors also thank Roderick Swaab and the anonymous reviewers for their guidance, Alexander Hirsch and Sara Sermarini for help running experiments, and Julia Bear, Nazli Bhatia, Brad Bitterly, Rachel Campagna, Peter Carne­ vale, Shereen Chaudhry, Matt Cronin, Jared Curhan, Deepak Malhotra, 14 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 Alex Rees-Jones, and Eric VanEpps for helpful comments. Studies 3b, 4: Subjective value Inventory Appendix A. ERRO measure The following items were adapted from Curhan et al. (2006), and rated on a 7-point likert scale from 1: “Not at all” to 7: “Perfectly”. We indicate the relevant subscale in brackets. We measured the economic relevance of relational outcomes (ERRO) as the difference between participants’ ratings of two questions (withinparticipant; rated from − 10: Much worse to +10: Much better). Imagine that you want to [buy product / hire service provider]. [counterpart] is [selling product / providing service]. You are planning to negotiate the price with [counterpart]. Please think about the interaction you will have with [counterpart]. Imagine that you negotiated with [counterpart], who is [selling product / providing service]. You and [counterpart] agreed on a price. By the end of the negotiation, your relationship with [counterpart] is OK. If instead, you had managed to develop a good relationship with [counterpart], how would that good relationship influence the value of the [product / service] you receive? Now, imagine that by the end of the negotiation, your relationship with [counterpart] is OK. If instead, you had managed to develop a bad relationship with [counterpart], how would that bad relationship influence the value of the [product / service] you receive? Items: Products: 1. [Relationship] Did the exchange with [counterpart] build a good foundation for a future relationship with them? 2. [Relationship] What kind of overall impression did [counterpart] make on you? (rated from 1: “Extremely negative” to 7: “Extremely positive”) 3. [Instrumental] How satisfied are you with the payment terms? 4. [Instrumental] Do you think the payment terms are consistent with objective standards? 5. [Process] Did the Boss consider your wishes, opinions, or needs? 6. [Process] Would you characterize the process as fair? 7. [Self] Did this negotiation positively or negatively impact your selfimage or your impression of yourself? Appendix C. Supplementary material Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi. org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2021.104108. References Amanatullah, E. T., & Morris, M. W. (2010). Negotiating Gender Roles: Gender Differences in Assertive Negotiating Are Mediated by Women’s Fear of Backlash and Attenuated When Negotiating on Behalf of Others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 256–267. Amanatullah, E. T., Morris, M. W., & Curhan, J. R. (2008). Negotiators Who Give Too Much: Unmitigated Communion, Relational Anxieties, and Economic Costs in Distributive and Integrative Bargaining. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 723–738. Amanatullah, E. T., & Tinsley, C. H. (2013). Punishing Female Negotiators for Asserting Too Much.or Not Enough: Exploring Why Advocacy Moderates Backlash against Assertive Female Negotiators. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 120(1), 110–122. Anderson, C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2006). Power, Optimism, and Risk-Taking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(4), 511–536. Anderson, C., & Thompson, L. L. (2004). Affect from the Top down: How Powerful Individuals’ Positive Affect Shapes Negotiations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95(2), 125–139. Babcock, L., Gelfand, M. J., Small, D., & Stayn, H. (2006). Gender Differences in the Propensity to Initiate Negotiations. In D. De Cremer, M. Zeelenberg, & J. K. Murnighan (Eds.), Social psycholoy and economics (pp. 239–262). Erlbaum. Babcock, L., & Laschever, S. (2004). Women Don’t Ask. Princeton University Press. Bazerman, M. H., Curhan, J. R., Moore, D. A., & Valley, K. L. (2000). Negotiation. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 279–314. Bazerman, M. H., & Neale, M. A. (1991). Negotiator Rationality and Negotiator Cognition: The Interactive Roles of Prescriptive and Descriptive Research. In H. P. Young (Ed.), Negotiation Analysis (pp. 109–130). The University of Michigan Press. Bazerman, M. H., & Neale, M. A. (1993). Negotiating rationally. Free Press. Bear, J. B., & Segel-Karpas, D. (2015). Effects of Attachment Anxiety and Avoidance on Negotiation Propensity and Performance. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 8(3), 153–173. Bear, J. B., Weingart, L. R., & Todorova, G. (2014). Gender and the Emotional Experience of Relationship Conflict: The Differential Effectiveness of Avoidant Conflict Management. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 7(4), 213–231. Becker, W. J., & Curhan, J. R. (2018). The Dark Side of Subjective Value in Sequential Negotiations: The Mediating Role of Pride and Anger. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(1), 74–87. Beest, I. V., Van Kleef, G. A., & Dijk, E. V. (2008). Get Angry, Get out: The Interpersonal Effects of Anger Communication in Multiparty Negotiation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(4), 993–1002. Bhatia, N., & Gunia. (2018). “I Was Going to Offer $10,000 But…”: The Effects of Phantom Anchors in Negotiation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 148, 70–86. Bottom, W. P., Holloway, J., Miller, G. J., Mislin, A. A., & Whitford, A. B. (2006). Building a pathway to cooperation: Negotiation and social exchange between principal and agent. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51, 29–58. Bowles, H. R., & Babcock, L. (2013). How can women escape the compensation negotiation dilemma? Relational accounts are one answer. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(1), 80–96. Bowles, H. R., Babcock, L., & Lai, L. (2007). Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations: Sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103(1), 84–103. • 3-seater couch • electronic vacuum • new smartphone Services: • someone to clean your apartment (one-time) • someone to move your furniture to a new apartment • someone to give you French lessons Appendix B. Measures Studies 1–4: Relational and Deal Term Concerns In Study 1, participants indicated how important they thought the following concerns were in their interaction with their counterpart (buyer or provider). Importance of each item was rated on a 5-point likert scale from 1: “Not at all” to 5: “Extremely”. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. I wanted to have a good relationship with [counterpart] I wanted [counterpart] to like me I wanted [counterpart] to trust me I wanted to get the best deal for myself I wanted to agree on a deal that will benefit both me and [counterpart] In Studies 2–4, we used a modified scale to measure importance of relational and deal term concerns: 1. I want to have a good relationship with [counterpart] 2. My relationship with [counterpart] is important to me 3. By the end of the negotiation, I want to make sure that [counterpart] likes me 4. I want to get the best deal terms for myself 5. The deal terms are important to me 6. By the end of the negotiation, I want to make sure that I get a good deal terms 15 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 Hüffmeier, J., Freund, P. A., Zerres, A., Backhaus, K., & Hertel, G. (2014). Being tough or being nice? A meta-analysis on the impact of hard- and softline strategies in distributive negotiations. Journal of Management, 40(3), 866–892. Kang, P., Anand, K. S., Feldman, P., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2020). Insincere negotiation: Using the negotiation process to pursue non-agreement motives. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 89, 103981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jesp.2020.103981 Kimmel, M. J., Pruitt, D. G., Magenau, J. M., Konar-Goldband, E., & Carnevale, P. J. (1980). Effects of trust, aspiration, and gender on negotiation tactics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(1), 9–22. Kong, D. T., Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2014). Interpersonal trust within negotiations: Meta-analytic evidence, critical contingencies, and directions for future research. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1235–1255. Koole, S. L., Steinel, W., & De Dreu, G. K. W. (2000). Unfixing the fixed pie: A motivated information-processing approach to integrative negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 975–987. Kroft, K., & Pope, D. G. (2014). Does online search crowd out traditional search and improve matching efficiency? Evidence from craigslist. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(2), 259–303. Magee, J. C., Galinsky, A. D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Wagner, R. F. (2007). Power, propensity to negotiate, and moving first in competitive interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(2), 200–212. Malhotra, D., & Bazerman, M. H. (2008). Negotiation genius: How to overcome obstacles and achieve brilliant results at the bargaining table and beyond. Bantam Dell. Malhotra, D., & Murnighan, J. K. (2002). The effects of contracts on interpersonal trust. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(3), 534–559. Mannix, E. A., Tinsley, C. H., & Bazerman, M. (1995). Negotiating over time: Impediments to integrative solutions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 62(3), 241–251. Mislin, A. A., Campagna, R. L., & Bottom, W. P. (2011). After the deal: Talk, trust building and the implementation of negotiated agreements. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115(1), 55–68. Molnar, A. (2018). SMARTRIQS: A Simple Method Allowing Real-Time Respondent Interaction in Qualtrics Surveys (Issue December). Moran, S., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2008). When better is worse: Envy and the use of deception. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 1(1), 3–29. Morris, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2000). How emotions work: The social functions of emotional expression in negotiations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 22(c), 1–50. Morris, M. W., Nadler, J., Kurtzberg, T. R., & Thompson, L. L. (2002). Schmooze or lose: Social friction and lubrication in E-Mail negotiations. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6(1), 89–100. Novemsky, N., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2004). What makes negotiators happy? The differential effects of internal and external social comparisons on negotiator satisfaction. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95(2), 186–197. O’Connor, K. M., & Arnold, J. A. (2001). Distributive spirals: Negotiation impasses and the moderating role of disputant self-efficacy. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 84(1), 148–176. O’Connor, K. M., & Arnold, J. A. (2011). Sabotaging the deal: The way relational concerns undermine negotiators. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(6), 1167–1172. Overbeck, J. R., Neale, M. A., & Govan, C. L. (2010). I feel, therefore you act: Intrapersonal and interpersonal effects of emotion on negotiation as a function of social power. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 112(2), 126–139. Patton, C., & Balakrishnan, P. V. S. (2010). The impact of expectation of future negotiation interaction on bargaining processes and outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 63(8), 809–816. Pinkley, R. L., Conlon, D. E., Sawyer, J. E., Sleesman, D. J., Vandewalle, D., & Kuenzi, M. (2019). The power of phantom alternatives in negotiation: How what could be haunts what is. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 151(April), 34–48. Pinkley, R. L., Griffith, T. L., & Northcraft, G. B. (1995). “Fixed Pie” a La Mode: Information availability, information processing, and the negotiation of suboptimal agreements. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 62(1), 101–112. Pinkley, R. L., Neale, M. A., & Bennett, R. J. (1994). The impact of alternatives to settlement in dyadic negotiation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 57(1), 97–116. Pruitt, D. G. (1998). Social conflict. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 470–503). McGraw-Hill. Pruitt, D. G., & Rubin, J. Z. (1986). Social conflict: Escalation, stalemate, and settlement (pp. 983–1023). New York: Random House. Raiffa, H. (1982). The art and science of negotiation. Harvard University Press. Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2(2), 121–139. Rudman, L. A., & Fairchild, K. (2004). Reactions to counterstereotypic behavior: The role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 157–176. Rutherford, D. (2013). Routledge dictionary of economics. Routledge. Schaerer, M., Schweinsberg, M., Thornley, N., & Swaab, R. I. (2020). Win-win in distributive negotiations: The economic and relational benefits of strategic offer framing. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 87. Schaerer, M., Swaab, R. I., & Galinsky, A. D. (2015). Anchors weigh more than power: Why absolute powerlessness liberates negotiators to achieve better outcomes. Psychological Science, 26(2), 170–181. Bowles, H. R., Thomason, B., & Bear, J. B. (2019). Reconceptualizing what and how women negotiate for career advancement. Academy of Management Journal, 62(6), 1645–1671. Brett, J. M., Olekalns, M., Friedman, R., Goates, N., Anderson, C., & Lisco, C. C. (2007). Sticks and stones: Language, face, and online dispute resolution. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 85–99. Campagna, R. L., Mislin, A. A., Kong, D. T., & Bottom, W. P. (2016). Strategic consequences of emotional misrepresentation in negotiation: The blowback effect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(5), 605–624. Carnevale, P. J., & Probst, T. M. (1998). Social values and social conflict in creative problem solving and categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74 (5), 1300–1309. Carnevale, P. J., & Pruitt, D. G. (1992). Negotiation and mediation. Annual Review of Psychology, 43(1), 531–582. Côté, S., Hideg, I., & van Kleef, G. A. (2013). The consequences of faking anger in negotiations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 453–463. Curhan, J. R., & Brown, A. D. (2012). Parallel and divergent predictors of objective and subjective value in negotiation. In K. S. Cameron, & G. M. Spreitzer (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship (pp. 579–590). Oxford University Press. Curhan, J. R., Elfenbein, H. A., & Eisenkraft, N. (2010). The objective value of subjective value: A multi-round negotiation study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(3), 690–709. Curhan, J. R., Elfenbein, H. A., & Kilduff, G. J. (2009). Getting off on the right foot: Subjective value versus economic value in predicting longitudinal job outcomes from job offer negotiations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 524–534. Curhan, J. R., Elfenbein, H. A., & Xu, H. (2006). What do people value when they negotiate? Mapping the domain of subjective value in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(3), 493–512. Curhan, J. R., Neale, M. A., Ross, L., & Rosencranz-Engelmann, J. (2008). Relational Accommodation in Negotiation: Effects of Egalitarianism and Gender on Economic Efficiency and Relational Capital. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 107(2), 192–205. Curhan, J. R., & Overbeck, J. R. (2008). Making a positive impression in a negotiation: Gender differences in response to impression motivation. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 1(2), 179–193. De Dreu, C. K. W., Beersma, B., Steinel, W., & Van Kleef, G. A. (2007). The psychology of negotiation: Principles and basic processes. In A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (2nd ed., pp. 608–629). Guilford Press. Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict: constructive and destructive processes. Yale University Press. Drolet, A., & Morris, M. (2000). Rapport in Conflict Resolution: Accounting for How Nonverbal Exchange Fosters Cooperation on Mutually Beneficial Settlements to Mixed-Motive Conflicts. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36(1), 26–50. Fisher, R., Ury, W., & Patton, B. (1991). Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (2nd ed.). Penguin Books. Friedman, R. A., Anderson, C., Brett, J., Olekalns, M., Goates, N., & Lisco, C. C. (2004). The positive and negative effects of anger on dispute resolution: Evidence from electronically mediated disputes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(2), 369–376. Friedman, R. A., Pinkley, R. L., Bottom, W. P., Liu, W., & Gelfand, M. (2020). Implicit theories of negotiation: Developing a measure of agreement fluidity. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 13(2), 127–150. Galinsky, A. D., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2015). Friend and Foe: When to cooperate, when to compete, and how to succeed at both. Crown Business. Gaspar, J. P., Methasani, R., & Schweitzer, M. (2019). Fifty shades of deception: Characteristics and consequences of lying in negotiations. Academy of Management Perspectives, 33(1), 62–81. Gelfand, M. J., & Brett, J. (2019). Big questions for negotiation and culture research. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 12(2), 105–116. Gelfand, M. J., Major, V. S., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L. H., & O’Brien, K. (2006). Negotiating relationally: The dynamics of the relational self in negotiations. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 427–451. Gelfand, M. J., Severance, L., Fulmer, C. A., & Al-Dabbagh, M. (2012). Explaining and predicting cultural differences in negotiation. In R. Croson, & G. E. Bolton (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Economic Conflict Resolution (pp. 331–356). Oxford University Press. Glick, P., & Croson, R. T. A. (2001). Reputations in Negotiation. In Wharton on making decisions (pp. 177–186). Gunia, B. C., Brett, J. M., & Gelfand, M. J. (2016). The Science of Culture and Negotiation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 78–83. Gunia, B. C., Brett, J. M., Nandkeolyar, A. K., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Paying a price: Culture, trust, and negotiation consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 774–789. Hart, E., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2020). Getting to less: When negotiating harms postagreement performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 156, 155–175. Holmstrom, B., & Milgrom, P. (1991). Multitask principal-agent analyses: incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 7(special_issue), 24–52. Howard, E. S., Gardner, W. L., & Thompson, L. L. (2007). The role of the self-concept and the social context in determining the behavior of power holders: Self-construal in intergroup versus dyadic dispute resolution negotiations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(4), 614–631. 16 E. Hart and M.E. Schweitzer Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 168 (2022) 104108 Van Kleef, G. A., & Dreu, C. K. W. D. (2010). Longer-term consequences of anger expression in negotiation: Retaliation or spillover? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(5), 753–760. Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2004). The interpersonal effects of emotions in negotiations: A motivated information processing approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(4), 510–528. Van Lange, P. A. M. (1999). The pursuit of joint outomes and equality of outcomes: An integrative model of social value orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(2), 337–349. Walton, R. E., & McKersie, R. B. (1965). A behavioral theory of labor negotiations. McGrawHill. Weber, J. M., Malhotra, D., & Murnighan, J. K. (2004). Normal acts of irrational trust: Motivated attributions and the trust development process. Research in Organizational Behavior, 26(04), 75–101. Weingart, L., Smith, P., & Olekalns, M. (2004). Quantitative coding of negotiation behavior. International Negotiation, 9(3), 441–456. White, J. B., Tynan, R., Galinsky, A. D., & Thompson, L. (2004). Face threat sensitivity in negotiation: Roadblock to agreement and joint gain. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 94(2), 102–124. Williamson, O. E. (1996). The mechanisms of governance. Oxford University Press. Wiltermuth, S. S., & Neale, M. A. (2011). Too much information: The perils of nondiagnostic information in negotiations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 192–201. Wiltermuth, S. S., Raj, M., & Wood, A. (2018). How perceived power influences the consequences of dominance expressions in negotiations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 146, 14–30. Schweinsberg, M., Ku, G., Wang, C. S., & Pillutla, M. M. (2012). Starting high and ending with nothing: The role of anchors and power in negotiations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 226–231. Schweitzer, M. E., Brodt, S. E., & Croson, R. T. A. (2002). Seeing and believing: Visual access and the strategic use of deception. International Journal of Conflict Management, 13(3), 258–375. Schweitzer, M. E., & Gomberg, L. E. (2001). The impact of alcohol on negotiator behavior: Experimental evidence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(10), 2095–2126. Schweitzer, M. E., & Kerr, J. L. (2000). Bargaining under the influence: The role of alcohol in negotiations. Academy of Management Perspectives, 14(2), 47–57. Shaughnessy, B. A., Mislin, A. A., & Hentschel, T. (2015). Should He Chitchat? The benefits of small talk for male versus female negotiators. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37(2), 105–117. Simon, H. A. (1991). Organizations and markets. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5 (2), 25–44. Soubbotina, T. P. (2004). Beyond economic growth: An introduction to sustainable development. World Bank Publications. Ten Velden, F. S., Beersma, B., & De Dreu, C. K. W. (2009). Goal expectations meet regulatory focus: How appetitive and aversive competition influence negotiation. Social Cognition, 27(3), 437–454. Thompson, L. L., Wang, J., & Gunia, B. C. (2010). Negotiation. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 491–515. Tinsley, C. H., O’Connor, K. M., & Sullivan, B. A. (2002). Tough Guys Finish Last: The perils of a distributive reputation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 88(2), 621–642. Van Kleef, G. A., & Côté, S. (2007). Expressing anger in conflict: When it helps and when it hurts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1557–1569. 17