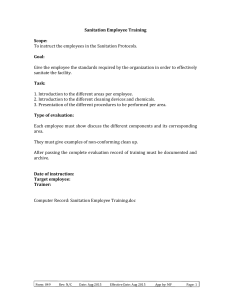

MZUZU UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF WATER AND SANITATION RESEARCH TOPIC: INVESTIGATION OF BARRIERS AND ENABLING FACTORS TO WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE ACCESS AMONG FEMALE SEX WORKERS IN LILONGWE DISTRICT - MALAWI STUDENT NAME: ANGELLAH CHIKOKO LUHANGA REGISTRATION NUMBER: MSAN 0721 FIRST SUPERVISOR: DR E. PHUMA SECOND SUPERVISOR: MR WILLY CHIPETA DATE: 11TH MAY 2023 i ABSTRACT Introduction: Advancing access to water, basic sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) is the first step of achieving each of the world’s crucial human rights issues, and it mostly affects the marginalized populations such as Females sex workers (FSWs). Females sex workers are part of the vulnerable segments in WASH, whose needs are not regarded fully and they face extra vulnerabilities due to nature of the lifestyle and places they operate, resulting into negative health outcomes. The global progress in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in relation to water and sanitation disguises the very limited progress in the vulnerable population with the emphasis of enhancing the principle of Living no one behind (LNOB) in the programming of WASH interventions. Achieving equitable access to WASH services requires paying special attention to the most disadvantaged segments of the population such as the female sex worker. Therefore, this study has been designed to explore the unmet WASH needs of FSWs in Lilongwe district. Aim of the study: The Main aim of this study is to investigate the barriers and enabling factors to water, sanitation and hygiene access among female sex workers in Lilongwe district. Methods and materials: A mixed method approach will be used. All Female Sex Workers accessing services in Drop-in Centres will be requested to participate in the study using a snowball rolling sampling technique. An interviewer administered questionnaire will be used to collect relevant information. Quantitative Data will be analysed using SPSS version 2.0 and qualitative data will be analysed using thematic analysis. Significance of the study: The results of this study will unlock issues surrounding Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) among Female sex workers. The information from the research will further assist policy makers to device Water Sanitation and Hygiene-based interventions for Female Sex Workers. Limitation of the study: Self-reported data always comes with limitation there is a high possibility that the respondents may provide responses that are socially acceptable rather than being truthful (social desirability). However, this will be mitigated by ab triangulating the collected data with records and the knowledge of key people that know the plight of sex workers including observational check lists. ii explaining properly to the participants the importance of providing honest answers, furthermore no identification will be utilised on questionnaire to ensure that participants are free to provide information. iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................................. ii Operational definitions .............................................................................. Ошибка! Закладка не определена. TABLE OF CONTENTS............................................................................................................................................. v CHAPTER 1 .0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Problem statement ............................................................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Justification of the study ................................................................................................................................. 9 1.3 Aim of the study............................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3.1 Main objective ............................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3.2 Specific objective.........................................................................................................................................10 1.3.4 Research Questions.....................................................................................................................................10 CHAPTER 2.0: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................................................................11 2.1 Access to water sanitation hygiene globally ..............................................................................................11 2.2 Access to water sanitation hygiene in Malawi..........................................................................................12 2.3 Access to wash for vulnerable populations. ...............................................................................................13 2.5 Stigma and discrimination and its links to water, sanitation, and hygiene ............................................16 2.6 The principle of leave no one behind in wash ( LNOB) ..........................................................................17 2.7 Legal framework of sex work ......................................................................................................................18 2.8 Research gap ..................................................................................................................................................19 CHAPTER 3.0 METHODOLOGY AND MATERIALS...........................................................................................20 3.1 Research design .................................................................................................................................................21 3.2 Study setting .......................................................................................................................................................21 3.3. Study population ..............................................................................................................................................21 3.4 Sampling and Sample size ..............................................................................................................................22 3.5 Inclusion and exclusion criteria ........................................................................................................................22 3.6. Data collection and management ..................................................................................................................22 3.7. Data analysis .....................................................................................................................................................23 Table 1: Methodology Matrix ................................................................................................................................23 3.8 Ethical considerations........................................................................................................................................25 3.9. Study Limitation ...............................................................................................................................................25 v 3.10 Dissemination of the results ............................................................................................................................25 REFERENCE ..............................................................................................................................................................26 ANNEXES ..................................................................................................................................................................31 Annex 1 : Ghart chart .........................................................................................................................................31 Annex 2: Budgets and Justification ....................................................................................................................32 Annex 3: Informed consent ................................................................................................................................34 Annex 4: Questionnaire in English .....................................................................................................................38 Annex 5: Observation checklist ..........................................................................................................................44 vi CHAPTER 1 .0 INTRODUCTION Advancing access to water, basic sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) is the first step of achieving each of the world’s crucial human rights issues, and it mostly affects the marginalized populations such as Females sex workers. The global progress in achieving the SDGs in relation to water and sanitation disguises the very limited progress in the vulnerable population with the emphasis of enhancing the principle of Living no one behind (LNOB) in the programming of WASH interventions, (SNV,2019). Reducing Inequalities in Water Supply, Sanitation, and Hygiene in the Era of the Sustainable Development Goals’ reveals a drastic change is required in the way countries manage resources and provide key services by targeting and reaching the vulnerable populations (World Bank, 2020). Achieving equitable access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services requires paying special attention to the most disadvantaged segments of the population such as the female sex workers (FSWs) (Shawmy, 2019). Due to the nature of their work, FSWs often experience high levels of stigma and discrimination resulting in negative health outcomes, (OSISA, 2018). Stigma and discrimination often result in lack of access to water and sanitation and poor hygiene standards. FSWs problems have been documented at household, community and by service provider with regards to water and sanitation access, (ASWA,2019). Yet, despite all the progress made to evaluate the access of vulnerable groups, important knowledge gaps still remain with respect to identifying their specific barriers and need regarding wash, (OSISA, 2018). Sub-Saharan Africa remains on the bottom of the world listing regarding increased access to safe drinking water and sanitation. Hence Malawi context in sub Saharan Africa is not exempted, In Malawi, sex work is highly stigmatized and sex workers face severe isolation from their family and friends(NAC, 2020).A sex worker is defined as a person who voluntarily does a commercial exchange of sex for money or goods (NAC, 2020).According to PLACE study (2018) there are more than 36700 Female sex workers in Malawi, and they live in 7 rest houses, lodges and houses with constricted space and extremely unhygienic conditions which makes them vulnerable to ill health. Furthermore, the Female sex workers have also been identified as being more vulnerable to HIV and AIDS and stigma and discrimination than the general population and this puts them at risk of contracting some opportunistic infections such as diarrhea, (NAC,2020). Therefore, it is more important to specifically explore the WASH needs of this population. While nascent research in Sub-Saharan Africa and Malawi has demonstrated the importance of assessing the WASH services among girls and women of reproductive age group, (Taulo et, al 2018, Saleem, et al, 2019, Cassiv, et al, 2018, Adams 2018, Adam, et al, 2018, Wayland,2018). Research has paid limited attention to exploring factors associated with unmet WASH needs among FSWs. This research is therefore aimed at investigating the barriers and enabling factors to water, sanitation and hygiene access among female sex workers in Lilongwe district exploring the unmet needs to access of water, sanitation and hygiene among the female sex workers in Lilongwe district. The findings of this study will be expected to guide policy makers responsible in designing programs to address challenges faced by the FSWs in WASH services in Malawi. 1.1 Problem statement Clean water and sanitation are basic human rights that shouldn’t be determined by a person’s economic situation. To ensure health for all by 2030, we must tell world leaders to invest in access to sanitation and hygiene for the most marginalized communities such as FSWs. Unfortunately, due to the stigma associated with this profession, sex workers do not receive any respect and are often deprived of basic human rights, including access to WASH facilities which puts them at risk of contracting WASH related diseases such as diarrhea, (Shawmy, 2019). Most sex workers live together in windowless rooms, as many as 30 people share one public bathroom and toilet. Additionally, more than 40% of sex workers are homeless and hence, live on the streets and rest houses (ASWA, 2019). This 8 tells us that they are dependent on public bathrooms for water and privacy. The water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) needs of Female Sex Workers (FSWs) is a new area of research which was often neglected (SNV, 2019). Most of the FSWs are HIV positive with prevalence of 46.9% and this puts them at risk of contracting other diseases such as diarrhea, more especially when their viral load is unsuppressed (NAC, 2020). This calls for a robust approach to empowering the FSWs to identify the major triggers of ill health and take preventive measures and empower them on good WASH practices. Several studies, (Taulo et, al 2018, Saleem, et al, 2019, Cassiv, et al, 2018, Adams 2018) have highlighted on WASH needs of women but there is limited research on minority groups such as female sex workers. Additionally, UN, 2017 emphases the importance of paying attention to the needs of People who are at risk of being left behind to be actively and meaningfully identified, included, engaged, and considered in all aspects of sanitation and hygiene programming. Strategies are needed to address existing inequalities and avoid creating new inequalities as side effects of programming. Without this, communities and areas will not achieve SDG 6 By 2030 (UN,2019). The principle of living no one behind seeks to reach the vulnerable populations, and combat stigma and discrimination and rising inequalities (OSISA, 2019). Therefore, this research is aimed at investigating and addressing the challenges faced by the female sex workers in accessing WASH services. 1.2 Justification of the study The results of this study will establish information on WASH challenges among the FSWs, that can be used in future in Water sanitation and hygiene-based interventions among this population. Furthermore, the findings of this study will also inform the policy makers and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO’s), to critically assess the issues surrounding WASH among FSWs and to device appropriate policies and interventions to prevent diseases in this population. 1.3 Aim of the study 1.3.1 Main objective The broad objective of this study is to investigate the barriers and enabling factors to water, sanitation and hygiene access among female sex workers in Lilongwe, district. 9 1.3.2 Specific objective 1. To assess level of access to WASH services among female sex works in the study area 2. To analyze barriers impeding access to WASH services among female sex workers in the study area 3. To assess enabling factors promoting access to WASH services among female sex workers in the study area 1.3.4 Research Questions 1. What is the level of access to WASH services among female sex works in the study area 2. What are barriers impeding access to WASH services among female sex workers in the study area 3. What are enabling factors promoting access to WASH services among female sex workers in the study area 10 CHAPTER 2.0: LITERATURE REVIEW This chapter presents the literature review and opens the door to the originality of the research. The purpose of the literature review is to show the current state of knowledge and therefore, to identify any gaps in the knowledge around the WASH needs of Female Sex workers. It also aims to ensure that this research does not duplicate any previous research and avoids the mistakes of previous work done. 2.1 Access to water sanitation hygiene globally Globally 1,2 billion people lack access to safely managed drinking water at home. Out of those, 1.2 billion people have basic drinking water service (WHO/UNICEF, 2021). Between 2015 and 2020, 107 million people gained access to safely managed drinking water at home, and 115 million people gained access to safe toilets at home (WHO/UNICEF, 2021). However, 8 out 10 people continue to lack basic drinking water services live in rural areas (WHO, UNICEF,2021). Regarding sanitation about3.6 billion people, nearly half the world’s population, do not have access to safely managed sanitation in their home. Of those, 1.9 billion people live with basic sanitation services, and 494 million people practice open defecation,(WHO/UNICEF, 2021).Furthermore, 2.3 billion people lack basic hygiene services, including soap and water at home. This includes 670 million people with no handwashing facilities at all. In rural settings, only 1 in 3 people have access to basic hygiene services such as soap and water at home, additionally 8 out 10 people continue to lack basic drinking water services live in rural areas, (WHO/UNICEF, 2021). Worldwide, hundreds of millions of people are affected by diseases such diarrhea, trachoma and schistosomiasis due to inadequate access to WASH, (Charles et al,2020). Universal access to safe drinking water, adequate sanitation, and hygiene has the potential to reduce the global disease burden by 10%. Furthermore, increasing access to safe drinking water and sanitation services can prevent many diarrheal deaths, (Pruss,2019). 11 2.2Trends of Water Sanitation Hygiene (WASH) access in Malawi Malawi is one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s most densely populated countries with about 18 million people spread over land area of 94,276 km2, giving a population density of 139 persons/km (NSO, 2018).Furthermore, is among the world’s poorest countries and most of its population still live below the international poverty line of $1.25 per day,(NSO, 2018).While impressive progress has been made to achieve the Millennium Development Goal target on water, 1.7million Malawians remain without access to a safe water facility. Although 67 per cent of Malawi’s households have access to drinking water, distribution among districts, and between urban and rural areas, is uneven, (WHO/UNICEF,2020). Improved drinking water sources are more common in urban areas at 87 per cent compared to 63 per cent in rural area, (NSHS,2018 - 2023). In rural areas, 37 per cent of households spend 30 minutes or more to fetch drinking water in comparison to 13 per cent in urban areas (WHO/UNICEF, 2020). Further analyses within districts also reveals the distribution of water services in some areas is poor and uneven. Only 77 per cent of water points nationwide are functional. The rest no longer work because of old age, catchment deterioration, neglect, lack of spare parts and inadequate community-based water management structures (Cassivi, et al,2018). Women and children shoulder the burden of poor access to water services as they often walk long distances to collect water for their families (Adams, 2018). Evidence shows that improving access to water significantly decreases the burden of water related diseases (WHO/UNICEF,2020). Poor sanitation and hygiene are major contributors to the burden of disease and child survival, costing Malawi US$57 million each year, or 1.1 per cent of national GDP, due to health costs and productivity losses (WHO/UNICEF, 2021). Although significant progress has been to decrease open defecation (OD), six per cent of the population still practice OD and only 26 per cent have access to basic sanitation services. Sanitation services are also unequally spread across the country such that 7 per cent of households practicing OD are in rural areas compared to one per cent in urban areas (WHO/ UNICEF, 2021). Changing behaviour around the use of latrines has been challenging as has 12 handwashing. Only 10 per cent of households in Malawi have handwashing facilities with soap (a proxy indicator for handwashing practice, (WHO/UNICEF,2021) The WASH sector is guided by the Government of Malawi’s (GoM) Development and Growth Strategy (MDGS-III) and the Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP II) in addition to other sector strategies. GOM also developed the National Sanitation and Hygiene Strategy of 2018-2023 which has been aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), specifically SDG 6.1 and 6.2, which aims for improved universal and sustainable access to safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene, and the elimination of open defecation by 2030. 2.3 Access to wash for vulnerable populations. According to Dickin (2018), vulnerability in WASH means denial or failure to ensure that people access water, sanitation and hygiene services. This could be in terms of non-existent or limited representation in decision making processes and therefore lacking a platform to voice concerns, lack of physical access to the services limited by technology and location, lack of access and control over resources to put up facilities and failure to access justice in instances of unfair denial, (Adams, 2018).There are several groups of marginalized populations such as female sex workers, women, the disabled and children to mention a few, (Somalia, et al, 2019).Somaila et al. (2019) further, highlights that vulnerable populations are at risk of facing stigma and discrimination which makes them to be unable to accesses basic health care including WASH services. This, therefore, increases the likeliness of the vulnerable populations contracting water-related health problems. In Malawi several studies have demonstrated that female sex workers like other highly stigmatized groups in society, avoid making themselves visible to authorities or refrain from accessing health services for fear of being identified, targeted and rejected, (Wanyenza 2021,scorgie, et al, 2019,NAC,2020).This makes it difficult for them to access health care services and information including WASH services which may expose them to water borne diseases .Additionally, NAC (2020),revealed that most Female sex workers leave in 13 informal settlements such as brothels, streets, and rest houses which lack proper water supply, hygiene and sanitation facilities which predisposes them to infection as a result of inadequate water and basic sanitation access. Lack of access to WASH facilities is linked to many other pressing problems therefore access to WASH facilities lead to better health, greater productivity, and more success according to the World Health Organization (2021). A study done by Sinharoy et, al, (2019) highlight the importance of addressing the water and sanitation needs of vulnerable populations such as female sex worker as essential to acknowledge and support the vision that United Nations has under their sustainable development goals. The United Nations declared access to water and sanitation to be a human right, simply because lack of water and sanitation in vulnerable populations is related to social and health implications throughout the world (UN,2021). A substantial number of studies worldwide demonstrates that vulnerable populations are unable to afford well-located formal housing due to high rates of poverty and unemployment (Fleifel. et al, 2019, Sinharoy, et al, 2019, Bisung, et al,2019, Dickson, et al, 2019). As a matter of fact, lack of adequate water and basic sanitation is perpetuated by poverty. Poverty drives people to settle for poor conditions. The informal settlements suffer the most with services pertaining to water and sanitation, (World Bank, 2020). It is important therefore to understand the extent in which vulnerable populations experience inadequate water and basic sanitation access to discover solution to this problem. There is a broad consensus in the international development community that equity in the water and sanitation sector needs to be the focus of all efforts, (UNOCHA, 2018). For this to happen there is need to prioritize reaching to disadvantaged populations and ensuring equitable and inclusive water sanitation and hygiene outcomes. But most countries are not making the right choices in prioritizing equity to get there, (UNICEF, 2019). A number of UN and other international studies indicate that even with the spending that is occurring in the WASH sector those in local rural communities, and other members of marginalized populations like female sex workers are the ones that still significantly lack access to the 14 essential services of water, sanitation and hygiene,(SNV, 2019,UN, 2021, World bank,2018,WHO/UNICEF, 2019).Additionally WHO/ UNICEF, (2021), revealed that lack of data about marginalized groups access to WASH is one of the first challenge governments need to address. This research study is therefore essential since it will unlock the WASH needs of FSWs and also add information on the vulnerable populations regarding WASH. 2.4 The link between wash and ill health The exclusion of any segment of the population from essential healthcare and water, sanitation and hygiene services not only puts these individuals at risk but creates an unnecessary and unacceptable risk to the entire population by allowing highly communicable diseases like diarrhea to spread more easily,(WHO/UNICEF, 2020). Improved Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) practices are critical contributors to illness prevention and response globallay, (World bank,2018). However, one-third of the world's population, mainly marginalized and vulnerable individuals living in many developing nations still lack access to WASH, (Dickin et al 2021). Most individuals in vulnerable areas suffer from water-borne diseases such as diarrhoea, acute respiratory infections, and skin infections because of contaminated water, inadequate sanitation, and poor hygiene, (Podder et al,2019). Additionally, due to poverty, limited access to basic WASH services, and inadequate housing, vulnerable populations are particularly exposed to illness, (Equal international, 2021). In addition, vulnerable populations have a low level of awareness and information about illness and WASH practices, which can lead to poor health and dangerous protective behaviours (Hsan et al. 2019).Therefore Understanding venerable populations WASH conditions, their vulnerability, knowledge and practices can aid in identifying elements that influence their protective behaviours when it comes to adopting response practices (Podder et al. 2019). In dealing with pandemics, knowledge enhancement and education initiatives are likely methods for improving the self-protection of marginalized people (Al-Hanawi et al. 2020). The water borne infectious agent spreads fast within the society and communities 15 therefore, protecting marginalized groups helps reduce the risk faced by individuals and society. Several studies conducted in developing countries such as,Ethiopia (Berhe et al. 2020) and Bangladesh (Islam et al. 2021) showed low knowledge on WASH issues among the vulnerable populations. Knowing, learning, and practising WASH can help people reduce their risks of contracting communicable diseases (Berhe et al. 2020). Some researchers have confirmed the link between knowledge and practice, as well as attitudes and behaviours (Nguyen et al. 2019). Previous research in the field has shown that people with high WASH and health-protection knowledge and attitudes are more likely to adopt safe hygiene and self-protection practices (Ozdemir et al. 2020).Therefore, it is critical that policymakers implement alternative and innovative measures to prevent further illnesses in the vulnerable populations such as the Female sex workers. 2.5 Stigma and discrimination and its links to water, sanitation, and hygiene Venerable groups often face discrimination and stigma from WASH in many ways. The human right to water entitles everyone without stigma and discrimination to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic us,(UNOCHA,2018). Additionally, the human right to sanitation entitles everyone without discrimination and discrimination to physical and affordable access to sanitation, in all spheres of life, which is safe, hygienic, secure, socially and culturally acceptable, which provides for privacy and ensures dignity, (Dery, et al, 2021). Stigma and discrimination often results in lack of access to water and sanitation and poor hygiene standards, (UNOCHA,2018).The lack of access to essential services is a symptom, while the root causes lie in stigma and discrimination,(MHRC,2018).Only through an understanding of these causes will it be possible to implement effective measures to improve access to WASH services for the vulnerable populations such as the female sex workers. Individuals who find themselves stigmatized are socially ostracized and denied access to water, sanitation and hygiene services, hence reinforcing the stereotype of uncleanliness and prolonging a vicious circle(WHO,UNICEF, 2018). 16 Several studies globally observed that vulnerable communities are disproportionately excluded from access to water and sanitation due to stigma and discrimination(Dery et al, 2021,Bisung et al, 2021, Mclean,2018). Another study done by, Dickin et al (2021), reveled that stigma and discrimination contributed to decreased ability to meet WASH needs and perform WASH behaviors among the vulnerable populations.Additionally several studies highlighted that stigma associated with the profession of sex work contributes to depriving sex workers of their basic human rights, including access to health services,(Shawmy, 2020, ASWA, 2021,NAC, 2020, Scorgie, et al, 2019).Furthermore, Sex workers in southern Africa are marginalized, face human rights violations, discrimination, harassment, and numerous other barriers to accessing healthcare which directly impact on their health,(ASWA,2021). It is essential therefore, that programming must help to reveal and address underlying and systemic causes of discrimination and stigma in WASH sector and work to change negative attitudes and harmful social norms. This requires direct attention and inclusion of those suffering stigma, marginalisation and those experiencing multiple forms of discrimination. Therefore, this research is essential to unlock issues pertaining to WASH needs among the female sex workers and find the solutions to this problem. 2.6 The principle of leave no one behind in wash ( LNOB) Access to water and sanitation are recognized by the United Nations as human rights fundamental to everyone’s health, dignity, and prosperity (UN, 2021). However, billions of people are still living without safely managed water and sanitation. Marginalized groups are often overlooked, and sometimes face discrimination, as they try to access the water and sanitation services they need (SNV, 2019). Marginalized groups such Female sex workers, children, refugees, disabled people, and many others also face active discrimination from, those planning and governing water and sanitation improvements and services, and other service users (WHO, UNICEF, 2020). To address this issue the Governments, need to take a human rights-based approach (HRBA) to water and sanitation improvements, so that no one gets left behind because all people are entitled to water and sanitation without discrimination.Leaving no one behind is the central promise 17 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to ensure that all people are accesses WASH services without hindrances, (UNOCHA,2018). In Malawi, the government aligned the National Sanitation and Hygiene Strategy of 20182023 with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) specifically, SDG 6.1 and 6.2, which aims for improved universal and sustainable access to safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene, and the elimination of open defecation by 2030. The strategy emphasizes the need of ensuring that all inequalities regarding WASH are addressed and all the Malawians have access to WASH regardless of their social status, (NSHS,2018- 2023).A society can only achieve high rates of public health, gender equity, educational attainment, and economic productivity when all of its members enjoy their rights to water and sanitation (WHO/UNICEF,2020). Respect for human rights must be integrated into development plans for all sectors, at all levels,(UN, 2021). SDGs, Goal 6 on clean water and sanitation, follows the guiding principle of leave no one behind, (McDemant,2018). However, barriers to accessing WASH services disproportionately affect the vulnerable populations. Previous joint WSSCC/OHCHR roundtables on Interdependencies and mutual impacts between the human rights to water and sanitation and other human rights, particularly for left behind groups and on Interdependencies between water and sanitation and other human rights highlighted that marginalized groups such as Female Sex Workers, migrants, refugees and others are often overlooked and sometimes face active discrimination from those planning and governing water and sanitation improvements and service.The participants to these meetings recommended that there is need to urgently give the floor directly to those in vulnerable situations, to influence policies (UN,2019,WHO/UNICEF, 2018).To make this happen we have to strategically aim to address the challenge of the inequalities that prevent the marginalized people from realizing their rights to safe water, sanitation and hygiene hence the importance of conducting this research among the female sex workers in Malawi. 2.7 Legal framework of sex work 18 The legal frameworks around sex work between countries vary considerably, (OSISA, 2020). Enforcement practices play a key part in determining outcomes, regardless of the law. In some cases, very harsh laws may not be strictly enforced, but in other cases more benign laws may be enforced in unfair or abusive ways,(ASWA, 2020).In Malawi sex work is legal but it is a highly stigmatized practice where police use laws against loitering and public disorder to prosecute FSWs and healthcare workers deny care on the basis of profession thereby preventing access to health care service,(FPAM, 2018).Furthermore, no provision in the Malawi Penal Code criminalises the selling of sexual services by a sex worker. Yet, some police officers in Malawi appear to be operating under the assumption that sex work is illegal. This assumption is based on an interpretation of section 146 of the Penal Code which prohibits a woman from living on the earnings of prostitution. Such an interpretation is then used to justify an arrest under section 184(c) of the Penal Code, which provides that a person found in a place in circumstances which lead to the conclusion that such person is there for an illegal purpose, is deemed a rogue and vagabond. Additionally, an approach of interpreting “where a woman knowingly lives wholly or in part on the earnings of prostitution” to apply to and criminalise the earnings of a sex worker violates the principle of legality because it broadens the offence beyond the plain meaning of its words and beyond the legislative intent of the section,(FPAM, 2020). Such an approach also violates the provisions of the Constitution requiring that a person not be convicted of an offence which clearly does not exist (MHRC,2018). 2.8 Research gap The gap to be addressed is to provide recommendations to meet the WASH needs of FSWs. The literature sparsely addresses any WASH needs for the female sex workers women during the perimenopause, with only fleeting, indirect references to needs for sanitation in Egypt (Shawmy e, 2020) and South Africa (ASWA, 2018) despite a projected rise in the number Female sex workers globally a. Nor does it explore practical aspects of WASH provision for FSWs. Whilst these needs are hidden from the literature, they warrant attention if the SDGs are to be met to ensure that no one is left behind. 19 2.9 Theoretical Framework Enabling factors + Access to WASH Well - being Addressing Barriers Figure 1. Conceptual framework of this study (Source: Shooya, 2017). As indicated in Figure 2, enabling factors and barriers affect access to WASH which then affects the well-being of communities. Enabling factors in this study include sources of accessing and the means of accessing water sanitation and hygiene. The means further consist of modes of accessing WASH and user participation. The barriers consist of social, environmental and technical constraints to accessing WASH. These have been expanded in the methodological matrix in Chapter 3 below. 20 CHAPTER 3.0 METHODOLOGY AND MATERIALS This section will discuss the research design, the study population, sampling technique, data collection, presentation of findings, data analysis, dissemination of findings, ethical considerations as well as the study variables. 3.1 Research design A cross – sectional descriptive mixed method approach will be utilised in this this research study. A mixed approach is a methodology for conducting research that involves collecting, analysing and integrating quantitative and qualitative research (Foodrisc ,2016). With the integration of the data, this approach highlights and provides greater understanding and in-depth knowledge. Furthermore, a quantitative approach will be used to gain information about the study area through generalized observations and surveys. Once the data is collected, it will be converted into numbers and displayed in graphs, models and tables. The practice of WASH and its related activities will be observed and documented as well as the alternatives used for the lack of accessible toilets and sanitation devices. 3.2 Study setting The study will be conducted in the four Drop-in Center (DICs) of the Pakachere Institute of Health and Development Communication (PIHDC) and observation will be conducted in the selected hotspots where FSWs reside. Drop-in-centers are stigma-free spaces where female sex workers (FSWs) access basic health care services such as HIV counseling and testing; STI screening and treatment; family planning information; and some contraceptive methods, including condoms and lubricants. PIHDC have four drop-in centers in Lilongwe namely Area 23 DIC, Area 36 DIC, Likuni DIC and area 25 DIC. Hotspots are places such as rest houses, bars or lodges where female sex workers reside. The study will be conducted from 1st January 2023 to 31st December 2023. 3.3. Study population The study population will include female sex workers patronizing the DICs in the Lilongwe district. Pakachere IHDC is currently reaching to 1180 female sex workers (PIHDC data 21 base- 2022). In Malawi it is estimated that there are more than 36,700 sex workers (NAC,2020), most of whom remain hidden and marginalized because of social stigma associated with sex work. 3.4 Sampling and Sample size Purposive sampling will be utilized to select the four DICs, 32 participants to be part of the focus group discussion, 8 from each DIC and 20 hotspots where observation will be conducted in Lilongwe District. Snowball rolling approach will be utilized to select the participants in this study. The observations will be conducted during outreach clinics which are conducted in the hotspots where female sex workers reside. The study sample size will be 298 study participants determined using the formula for systematic random sampling using single proportions (Yamane, 1967). N The employed sample size formula will be:n = 1+N(e2 ) Where n = Sample size N= expected proportion of Female Sex Workers accessing DICs = 1180 (PIHDC data base, 2022) and e= absolute precision (5%) = 0.005. Therefore, from the above sample size is: n= 1180 = 298 1 + 1180 ∗ 0.05 ∗ 0.05 3.5 Inclusion and exclusion criteria The inclusion criteria will be Female Sex Workers 18 years old and above who will give consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria will include Female Sex Workers who will not be willing to sign the informed consent form and Female sex workers less than 18 years of age. 3.6. Data collection and management The data collection will start with the review of secondary data including the DIC records. An interviewer-administered questionnaire will be utilized to obtain data relevant to the 22 study in a face-to-face interview. Additionally, focus group discussions from the selected female sex workers will be conducted. A structured observation check list will also be utilized to collect data on the WASH practices at hotspot level. The questionnaire and the checklist will be adopted from the published studies and modified to suit the responding population. Four research assistants who are the outreach workers working in the DICs will be employed to conduct the interviews since they have good skills in handling FSWs. 3.7. Data analysis Qualitative data will be analysed using content analysis based on key themes generated from the objectives of the study. Some of the data will be analysed in verbatim (data presented in the form in which the respondent offered it). Additionally, quantitative data will be analyzed using a statistical software package for social sciences version 23 (SPSS V.23). A regression model will be used to show the significance of predictor’s variables. Statistical tests will be computed to show an association between the predictor’s variables and the outcome variables. Frequency tables, pie charts and bar graphs will be generated in presenting the research results. Differences between the parameters of estimate will be deemed statistically significant at p < 0. 005.The detailed data analysis methods are detailed in Table 1 below. Table 1: Methodology Matrix Specific objectives Variables Data collection Methods tool SPSS V 23 WASH Content among FSWs with access to Observation female sex works in the improved study area and checklist Unimproved water source and un improved sanitation 23 analysis Descriptive analysis Linear regression – P Value of 0.005 Access to Improved data analysis To assess level of access to The proportion of Questionnaire services of Availability of handwashing facilities with water and soap To analyze barriers Stigmatized and Questionnaire impeding access to WASH discriminated services among female sex Attitudes workers in the study area Observation towards check list SPSS V 23 content analysis Chi-square, logistic WASH regression – P Value of Economic challenges 0.005 Distance to water collection points Administration of WASH Infrastructure Time allocation on communal taps To assess enabling factors Knowledge and Questionnaire promoting access to WASH practice on WASH services among female sex Health workers in the study area Observation seeking checklist SPSS V 23 Content analysis logistic regression - behaviors P Value of 0.005 ownership of water, Chi- square hygiene and sanitation Access to health care services and information 24 3.8 Ethical considerations Respondent’s rights to make independent decisions on whether to participate in the study or not will be respected. The participants will sign an informed consent form, which will be an agreement by a prospective subject to voluntarily participate in a study after learning all of the pertinent details about it. Additionally, no unauthorized person will get hold of raw data and the completed questionnaires will be in safe keeping and not available for any other purpose than in this research. Furthermore, the research proposal will be reviewed by the Mzuzu University Research and Ethics Committee and permission will be obtained from Pakachere IHDC to conduct the study in the Drop-in Centers in Lilongwe district. 3.9. Study Limitation Since this study will use questionnaires,self-reported data always comes with limitation since there is a high possibility that the respondents may provide responses that are socially acceptable rather than being truthful (social desirability).However this will mitigate by explaining properly to the participants the importance of providing honest answers, furthermore no any identification will be utilised on questionnaire to ensure that participants are free to provide the required information. 3.10 Dissemination of the results The final report of the research findings will be submitted to the Mzuzu University Research and Ethics Committee, Mzuzu University Library, the National Health Sciences Research Committee (through MZUNI), The University Research and Publication Committee (URPC) (through the MZUNI Secretariat) and Pakachere IHDC secretariate. The findings of the research study will also be disseminated through conference journal articles. 25 REFERENCE 1. Adams, E.A. and Smiley, S.L. (2018) Urban-rural water access inequalities in Malawi: implications for monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals. Natural Resources Forum 42(4), 217-226. 2. WHO / UNICEF. (2019). Water sanitation and hygiene annual report. 3. WHO,2018. “Sanitation”. https://www.who.int/topics/sanitation/en/ 4. UNITED NATIONS (UN) (2021) Summary Progress Update: SDG 6 — water and sanitation for all 5. SNV, 2019. Leaving no one behind: National Rural Sanitation and Hygiene Programme of Bhutan [Research Brief]. The Hague: SNV. 6. World Bank (2018) Why a human rights-based approach to water and sanitation is essential for the poor. 7. Shawmy S Chowdhury,(2019).Ensuring access to water and sanitation in Bangladesh’s brothels, India, Journal of Social Service Research, 39:4, 552-561, DOI: 10.1080/01488376.2019.876. 8. ASWA (2019). Every sex worker has a story to tell about violence: Violence against sex workers in Africa. 9. OSISA (2018). Baseline assessment on sex workers’ access to comprehensive health care in 5 SADC countries, unpublished 10. National Aids Commission of Malawi HIV/AIDS FSW REPORT (2020) 11. PLACE STUDY REPORT IN MALAWI SEPTEMBER 2018 12. Taulo, S., Kambala, C., Kumwenda, S. and Morse, T. (2018) Review Report of the National Open Defecation Free (ODF) and Hand Washing with Soap (HWWS) Strategies. 13. Saleem, M., Burdett, T. and Heaslip, V. (2019) Health and social impacts of open defecation on women: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 19(1), 158-158. 26 14. Cassivi, A., Waygood, O. and Chang Dorea, C. (2018) Quality of Life Impacts Related to the Time to Access Drinking Water in Malawi. Journal of Transport & Health 5, S15 15. Adams, E.A. (2018) Intra-urban inequalities in water access among households in Malawi's informal settlements: Toward pro-poor urban water policies in Africa. Environmental Development 26, 34-42 16. Wayland, J. (2018) Constraints on aid effectiveness in the water, Sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector: evidence from Malawi. African Geographical Review, 1-17. 17. WHO/UNICEF (2021) Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene : 2020 Update and SDG Baselines 18. Charles, R. C., Kelly, M., Tam, J. M., Akter, A., Hossain, M., Islam, K., et al. (2020). Humans surviving cholera develop antibodies against Vibrio cholerae o-specific polysaccharide that inhibit pathogen motility An updated analysis with a focus on low and middle -income countries 19. Prüss-Ustün, A., Wolf, J., Bartram, J., Clasen, T., Cumming, O., Freeman, M. C., et al. (2019) Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene for selected adverse. mBio, 11(6), e02847-20 health outcomes: - in countries. 20. Malawi National Statics Office 2018 report 21. Malawi National Sanitation and Hygiene Strategy 2018-2023 22. WHO/UNICEF Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2020: Five years into the SDGs ISBN: TBD © 23. Dickin, S. (2018) Gender and water security in Burkina Faso: lessons for adaptation. SEI Policy Brief 24. Soumaila, K. I., Niandou, A. S., Naimi, M., Mohamed, C., & Schimmel, K. (2019). Analysis of Water Resources Vulnerability Assessment Tools 25. Wanyenze RK, Musinguzi G, Kiguli J, et al. “When they know that you are a sex worker, you will be the last person to be treated”: Perceptions and experiences of female sex workers in accessing HIV services in Uganda. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2017;17(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12914-017-0119- 27 26. Scorgie F, Nakato D, Harper E, et al. “We are despised in the hospitals”: sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. Cult Health Sex. 2019;15(4):450–465. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.763187 27. Nicole Y. Frascino,1 Jessie K. Edwards,1 Michael E. Herce,2,3 Joanna Maselko,1,4 Audrey E. Pettifor,1 Nyanyiwe Mbeye,5 Sharon S. Weir,1,4 and Brian W. Pence (2021) Differences in access to HIV services among Malawian women at social venues who engage in formal sex work or informal sex work or who do not engage in sex work in Malawi. 28. World Health Organization and UNICEF. International journal of hygiene and environmental health, 222(5), 765–7Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2020: Five years into the SDGs [PDF – 164 pages]. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2021 29. Sinharoy, S. S., Pittluck, R., & Clasen, T. (2019). Review of drivers and barriers of water and sanitation policies for urban informal settlements in low-income and middle-income countries. Utilities policy, 60, 100957. 30. Fleifel, E., Martin, J., & Khalid, A. (2019). Gender Specific Vulnerabilities to Water Insecurity 31. Bisung, E. and Dickin, S. (2019) Concept mapping: Engaging stakeholders to identify factors that contribute to empowerment in the water and sanitation sector in West Africa. SSM – Population Health, 9 (100490). 32. Dickin, S., Bisung, E., Nansi, J., and Charles, K. (2021). Empowerment in water, sanitation and hygiene index. World Development, 137 (105158). 33. Dickin, S. and Bisung, E. (2019) Empowerment in WASH Index. SEI Policy Brief 34. Bori, S., Dickin, S., Bisung, E., Atengdem, J. (2019) Measuring empowerment in WASH : Ghana. SEI Policy BriefUNOCHA, World Humanitarian Data and Trends, OCHA, 2018, p33. 5 35. UNICEF, Water under fire, 2019 28 36. Podder D., Paul B., Dasgupta P. A.,Pal A.& Roy S.2019 Community perception and risk reduction practices toward malaria and dengue: a mixed-method study in slums of Chetla, Kolkata Indian Journal of Public Health63, 178 37. 9 Equal International (2020). Operational toolkit for social inclusion in Health Preparedness Plans 38. Hsan K.Naher Griffiths M.Shamol H. & Rajman M.2019 Factors associated with the practice of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) among the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 9 (4), 794–800. 39. Al-Hanawi M. K., Angawi K., Alshareef N., Qattan A. M. N., Helmy H. Z., Abudawood Y., Alqurashi M., Kattan W. M., Kadasah N. A., Chirwa G. C. &Alsharqi O.2020 Knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19 among the public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study Frontiers in Public Health 40. Berhe A. A.Aregay A. D.AbrehaA. A.Fente K. A.Mamo N. B.2020 Knowledge, attitude, and practices on water, sanitation, and hygiene among rural residents in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia Journal of Environmental and Public Health20205460168 41. ISlam S., Emran G. I.Rahman E., Banik R., Sikder T., Smith L. & Hossain S.2021 Knowledge, attitudes and practices associated with the COVID-19 among slum dwellers resided in Dhaka City: a Bangladeshi interview-based survey Journal of Public Health 43 (1), 13–25 42. Nguyen T. P. L. & Pattanasri S.2022 The influence of nationality and sociodemographic factors on urban slum dwellers’ threat appraisal, awareness, and protective practices against COVID-19 in Thailand The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene107 (1),169–174doi:10.4269/ajtmh.21-1096 43. Dery, F., Bisung, E., Dickin, S. and Atengdem, J. (2021). ‘They will listen to women who speak but it ends there’: examining empowerment in the context of water and sanitation interventions in Ghana. H2Open Journal, doi.org/10.2166/h2oj.2021.100 29 44. Malawi Human Rights Commission. (2018). A Report on monitoring of childcare institutions in Malawi 2017. Lilongwe: Malawi Human Rights Commission. 45. Bisung, E., and Dickin, S. (2021). Who does what and why? Examining intrahousehold water and sanitation decision making and autonomy in Acetify North, Ghana. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 11(5) doi: 10.2166/washdev.2021 46. MacLean, S. A., Lancaster, K. E., Lungu, T., Mmodzi, P., Hosseinipour, M. C., Pence, B. W., … Miller, W. C. (2018). Prevalence and Correlates of Probable Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Among Female Sex Workers in Lilongwe, Malawi. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(1), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9829-9 47. McDermont, S. (2016). Gendered development: the female experience in Malawi 48. Family Planning Association of Malawi. Counting The Uncatchables: Report of the Situation Analysis of the Magnitude, Behavioral Patterns, Contributing Factors, Current Interventions and Impact of Sex Work in HIV Prevention in Malawi. Lilongwe, Malawi. 49. Memorandum on s146 of Malawi Penal Code 50. Shoona, B. (2007). Understanding the urban poor’s vulnerabilities in sanitation and water supply. Innovations for an Urban World, the Rockefeller Foundation’s Urban Summit, Bellagio, Italy, July. 51. Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics, An Introductory Analysis, 2nd Ed., New York: Harper and Row 30 ANNEXES Annex 1 : Ghart chart ACTIVITY MONTH Jan Feb Mar- June July Aug 2023 2023 May 2023 2023 2023 2023 2023 Identify research topic Literature review and proposal writing Submission of proposal and clearance Data collection Data analysis Report writing Submission of dissertation 31 Sep Oct Nov Dec 2023 2023 2023 Disseminati on of findings Annex 2: Budgets and Justification ITEMS Pens QUANTITY 1box PRICE / TOTAL UNIT AMOUNT K1000 K 1,000.00 Justification To be used during data collection Rim of papers 1 K12,000 K 12,000.00 (A4) To be used during for data collection Handbooks 1Pack K10,000 K 10,000 To be used by data collectors Printing 360 K50.00 K 18,000.00 questionnaires Payment for printing services at the bureau Printing 3 K5000 K 15,000.00 report Payment for printing services at the bureau 32 Binding 3 K5,000 K 15,000.00 Payment for binding services at the bureau Lunch 4for 5days Allowance for K6,000/ K To day 120,000.00 during data buy lunch data collection collectors MZUNIREC 1 K 150 usd K 150,000 1 1 K 350,000 . Administration fee Fee Total 00 MZUNIREC 10% of the K49,900 K 35,000. 00 budget Grand total 1 Proposal processing fee 1 K 385,000.00 33 Annex 3: Informed consent Mzuzu University Research Ethics Committee (MZUNIREC) Informed Consent Form for Research in Master of science in Sanitation Introduction I am Angellah Chikoko Luhanga from Mzuzu University. We are doing research on Water, sanitation and hygiene practices as predictors of diarrhea occurrence among Female Sex Workers in Lilongwe district in Malawi. This consent form may contain words that you do not understand. Please ask me to stop as we go through the information, and I will take time to explain. If you have questions later, you can ask them of me or of another researcher. Purpose of the research This research aims to explore the unmet needs of access to Water Sanitation and hygiene among the Female Sex Workers in Lilongwe district - Malawi. Type of Research Intervention This research will involve your participation in an individual interview. Participant Selection 34 You are being invited to take part in this research because you are one of the Female Sex worker in Lilongwe district and your responses will us to address the challenges that affects FSWs regarding WASH and diarrhea issues. Voluntary Participation Your participation in this research is entirely voluntary. It is your choice whether to participate or not. If you choose not to participate nothing will change. You may skip any question and move on to the next question. Duration The research takes place for a period of 1 year. Risks You do not have to answer any question or take part in the discussion/interview/survey if you feel the question(s) are too personal or if talking about them makes you uncomfortable.) Reimbursements You will not be provided any incentive to take part in the research. Sharing the Results The knowledge that we get from this research will be shared with you and your community before it is made widely available to the public. Following, we will publish the results so other interested people may learn from the research. Who to Contact If you have any questions, you can ask them now or later. If you wish to ask questions later, you may contact: Mrs. Angellah Chikoko Luhanga on 0888554991/0993113240 35 This proposal has been reviewed and approved by Mzuzu University Research Ethics Committee (MZUNIREC) which is a committee whose task it is to make sure that research participants are protected from harm. If you wish to find about more about the Committee, contact Mr. Gift Mbwele, Mzuzu University Research Ethics (MZUNIREC) Administrator, Mzuzu University, P/Bag 201, Luwinga, Mzuzu 2, Phone: 0999404008/0888641486 Do you have any questions? Part II: Certificate of Consent I have been invited to participate in research about Water, sanitation and hygiene practices as predictors of diarrhea occurrence among Female Sex Workers in Lilongwe district in Malawi I have read the foregoing information, or it has been read to me. I have had the opportunity to ask questions about it and any questions I have been asked have been answered to my satisfaction. I consent voluntarily to be a participant in this study Print Name of Participant__________________ Signature of Participant ___________________ Date ___________________________ Day/month/year If illiterate 1 I have witnessed the accurate reading of the consent form to the potential participant, and the individual has had the opportunity to ask questions. I confirm that the individual has given consent freely. 1 A literate witness must sign (if possible, this person should be selected by the participant and should have no connection to the research team). Participants who are illiterate should include their thumb print as well. 36 Print name of witness____________ Signature of witness Thumb print of participant _____________ Date ________________________ Day/month/year Statement by the researcher/person taking consent I have accurately read out the information sheet to the potential participant, and to the best of my ability made sure that the participant understands the research project. I confirm the participant was given an opportunity to ask questions about the study, and all the questions asked by the participant have been answered correctly and to the best of my ability. I confirm that the individual has not been coerced into giving consent, and the consent has been given freely and voluntarily. Signature of Researcher /person taking the consent__________________________ Date ___________________________ Day/month/year 37 Annex 4: Questionnaire in English This study is aimed at assessing the WASH needs for the FSWs to guide public health action. The information obtained from the interviews will be confidential and your consent is requested. Hence as the respondent you are requested to give correct and honest information. SECTION A: DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION Q1. How old are you? a. 18 -24 b. 24- 35 c. 36 -45 d. 45- 60 Q2. How far did you go with Education? a. Primary school b. Secondary school c. Tertiary Q3.Place of residence? a. Bar based. b. Home based. c. Street based. SECTION B:KNOWLEDGE ON WASH Q4. Can unsafe water cause diarrheal diseases? a. Yes b. No Q5. Can water get contaminated if not properly stored? a. Yes b. No Q6. What are the consequences of improper waste disposal? a .Expose to diseases b. Does not expose diseases. 38 Q7. Have you got information on WASH in the last 3 month? a. yes b. no Q8. Where did you get information? a. Friends b. Health facility c. News paper d. Radio/ TV SECTION C: HYGIENE PRACTICES Q9. When do you wash your hands? a. Before having food b. After having food c. After going to toilet d. Before taking medication e. Before feeding baby f. After changing baby nappies Q10. What do you use when washing hands? a. Soap b. Water only c. Ash Q11. How often do you take bath? a. Everyday b. Every alternate day c. Twice a week d. Once a week or less frequent Q12. Why don’t you take bath frequently? a. Don’t like to b. Don’t think necessary. c. Due to lack of Water 39 d. Can’t afford soap. Q13.How many times do you brush your teeth in a day? a. Once every day b. Twice or more every day c. Less than once everyday SECTION D: ACCESS TO WATER Q14.What is the Main source of drinking water at your household? a. Piped water. b. Borehole c. Well d. kiosk Q16.How do you treat water before drinking?(multiple answers) a. Boil b. Filter c. Chlorination d. don’t treat. Q12.Does your household have to pay for water? a. Yes b. No Q17. Do you manage to pay your water bills without problems? a. Yes b. No Q18. Is the water you are receiving enough to satisfy your needs? a. Yes b. No Q19.Have you ever received any information or training about hygiene? a. Yes 40 b. No Q20. If yes, where did you receive the information from? a. Family members b. Support Group c. Health Facility d. Radio/TV e. Newspaper/Magazine Q 21.Do FSWs have increased need for better hygiene? a. Yes b. No Q22. Why do you think FSWs have increased need? (Multiple response) a. They are vulnerable for illnesses. b. To prevent c. Don’t know. Q23. How do you think FSWs can prevent diarrhoea? a. Drinking safe water b. Eating clean food c. Maintaining good hygiene d. Keeping surrounding clean e. Faeces management SECTION E: ACCESS TO SANITATION Q24.What type of latrine do you use? a. VIP improved latrine b. Traditional pit latrines c. Flush toilet with a septic tank Q25. Do you share the latrine? a. Yes b. No Q26. How many people use one latrine at your hotspot. 41 a. Yes b. No Q27. Do you have a hand washing facility near your toilet? a. Yes b. No Q28.IS soap always available for you hand washing? a. Yes b. No Q.29. Where you dispose of your refuse in the right place? a. Bin ( collected by city council) b. Rubbish pit c. Anywhere SECTION F: Health in relation to WASH Q30.Have you ever been sick for the past 3months. a. Yes b. No Q31. Did you suffer from any of the diseases the past 3 months?(Multiple answers) a. Diarrhoea b. Dysentery c. Skin infections d. Typhoid e. Conjunctivitis Q 32. Do you take medication when sick? a. Yes b. No Q33. Where do get the treatment when sick? a. At home only 7 b. Government hospital c. Private health facility d. Private phamarcy 42 e. Faith-healers Q 34.Did service providers give you WASH information? a. Yes b. No SECTION G: FSTIGMA AND DESCRIMINATION Q35. Have you ever disclosed to anyone that you are an FSW? a . Yes b . No Q36. If no, why did you not disclose? a. Fear b. stigma c. discrimination d. didn’t know. Q37. Have you ever been discriminated or stigmatized by a family member? a. Yes b. No Q38. Have you ever been discriminated or stigmatized when accessing community? people. a. Yes b. no Q39. Have you ever been discriminated or stigmatized by a health care worker? a. Yes b. No Q40. Have you ever been discriminated or stigmatized by a family member when accessing the toilet? c. Yes d. No Q41. Have you ever been discriminated or stigmatized by community people when accessing the toilet? c. Yes 43 d. no Q48. Have you ever been discriminated or stigmatized by a family member when accessing water? a. Yes b. No Q49. Have you ever been discriminated or stigmatized by community people when accessing water? a. Yes b. No Thank you for your time. Annex 5: Observation checklist Serial # Statement / Question Answer Are all the latrines functioning properly? Yes 1. No Are there separate latrines for women and men ? 2 Yes No Is there easy access to the women’s latrines? 3. Yes No Number of people per latrine ? 1-5 4 6- 10 11-20 21-30 31 and more Condition of latrines Good 44 5 Fair (needs repair) Bad (needs replacement 6 Are there hand washing facilities. Yes near the latrine? No What type of water is available ? Tap water. 7 share a common container. 8 Do the hotspot always have enough water and Yes soap No Sometimes Is there soap by the hand washing facility? 9 Yes No Do FSWs use the hand washing facilities? 10 Often Quite often Not often 11 What kind of source of water is there Well Tap water. Borehole none 12 Is the area around the water point clean, free Yes from visible garbage and puddles? No 45