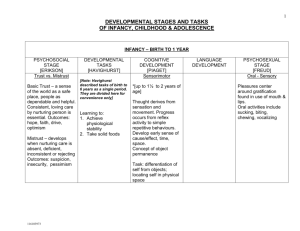

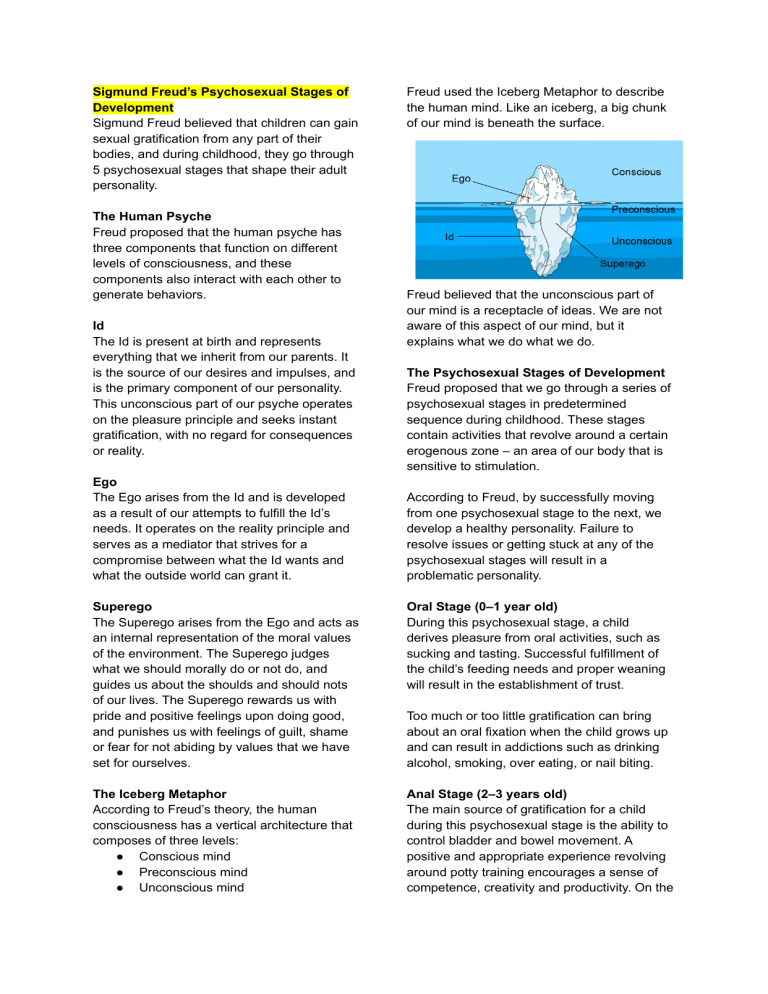

Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Stages of Development Sigmund Freud believed that children can gain sexual gratification from any part of their bodies, and during childhood, they go through 5 psychosexual stages that shape their adult personality. The Human Psyche Freud proposed that the human psyche has three components that function on different levels of consciousness, and these components also interact with each other to generate behaviors. Id The Id is present at birth and represents everything that we inherit from our parents. It is the source of our desires and impulses, and is the primary component of our personality. This unconscious part of our psyche operates on the pleasure principle and seeks instant gratification, with no regard for consequences or reality. Ego The Ego arises from the Id and is developed as a result of our attempts to fulfill the Id’s needs. It operates on the reality principle and serves as a mediator that strives for a compromise between what the Id wants and what the outside world can grant it. Freud used the Iceberg Metaphor to describe the human mind. Like an iceberg, a big chunk of our mind is beneath the surface. Freud believed that the unconscious part of our mind is a receptacle of ideas. We are not aware of this aspect of our mind, but it explains what we do what we do. The Psychosexual Stages of Development Freud proposed that we go through a series of psychosexual stages in predetermined sequence during childhood. These stages contain activities that revolve around a certain erogenous zone – an area of our body that is sensitive to stimulation. According to Freud, by successfully moving from one psychosexual stage to the next, we develop a healthy personality. Failure to resolve issues or getting stuck at any of the psychosexual stages will result in a problematic personality. Superego The Superego arises from the Ego and acts as an internal representation of the moral values of the environment. The Superego judges what we should morally do or not do, and guides us about the shoulds and should nots of our lives. The Superego rewards us with pride and positive feelings upon doing good, and punishes us with feelings of guilt, shame or fear for not abiding by values that we have set for ourselves. Oral Stage (0–1 year old) During this psychosexual stage, a child derives pleasure from oral activities, such as sucking and tasting. Successful fulfillment of the child’s feeding needs and proper weaning will result in the establishment of trust. The Iceberg Metaphor According to Freud’s theory, the human consciousness has a vertical architecture that composes of three levels: ● Conscious mind ● Preconscious mind ● Unconscious mind Anal Stage (2–3 years old) The main source of gratification for a child during this psychosexual stage is the ability to control bladder and bowel movement. A positive and appropriate experience revolving around potty training encourages a sense of competence, creativity and productivity. On the Too much or too little gratification can bring about an oral fixation when the child grows up and can result in addictions such as drinking alcohol, smoking, over eating, or nail biting. contrary, anal fixations can translate into obsession with perfection, extreme cleanliness, and control or the opposite which is messiness and disorganization in adulthood. Phallic Stage (3–6 years old) During this psychosexual stage, the erogenous zone is the genitals. Boys start to perceive their father as rivals for their mother’s affections, while girls feel similarly towards their mother. Freud used the term “The Oedipus Complex” to describe boys’ attachment towards their mother, and Carl Jung later coined the term “The Electra Complex” to describe girls’ attachment towards their father. Fear of punishment leads to repression of feelings toward the opposite sex parent, and fixation at this stage may bring about sexual deviancy or weak sexual identity. Latency Stage (6 years to puberty) During this psychosexual stage of development, sexual urges are usually repressed. Children spend most of their time interacting with same sex peers, engaging in hobbies and acquiring skills. Adults who are fixated at this stage are immature and have a hard time forming meaningful relationships. Genital Stage (Puberty onward) During the last psychosexual stage, the erogenous zone is genitals. Individuals’ sexual urges are reawakened and are directed toward opposite sex peers. However, unlike at the phallic stage, the sexuality at the genital stage is consensual. People who completed the earlier stages successfully become well-adjusted, caring and secure individuals at this stage. While younger children are mostly ruled by their id and focus on their wants, individuals at this stage have fully formed ego and superego. They can balance their wants (id) with the reality (ego) and ethics (superego). Significance of Freud’s Psychosexual Theory One importance of Sigmund Freud’s psychosexual theory is his emphasis on early childhood experiences in the development of personality and as an influence on later behaviors. The relationships that individuals cultivate, their views about themselves and others, and their level of adjustment and well-being as adults are all influenced by the quality of experiences that they have had during the psychosexual stages. Despite being one of the most complex and controversial theories of child development, we cannot discount the important ideas that Freud has contributed to the field of psychology and human development. Erikson's Stages of Development Erik Erikson was an ego psychologist who developed one of the most popular and influential theories of development. While his theory was impacted by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud's work, Erikson's theory centered on psychosocial development rather than psychosexual development. The stages that make up his theory are as follows: Stage 1: Trust vs. Mistrust (Infancy from birth to 18 months) Stage 2: Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (Toddler years from 18 months to three years) Stage 3: Initiative vs. Guilt (Preschool years from three to five) Stage 4: Industry vs. Inferiority (Middle school years from six to 11) Stage 5: Identity vs. Confusion (Teen years from 12 to 18) Stage 6: Intimacy vs. Isolation (Young adult years from 18 to 40) Stage 7: Generativity vs. Stagnation (Middle age from 40 to 65) Stage 8: Integrity vs. Despair (Older adulthood from 65 to death) Let's take a closer look at the background and different stages that make up Erikson's psychosocial theory. conflict that serves as a turning point in development. In Erikson's view, these conflicts are centered on either developing a psychological quality or failing to develop that quality. During these times, the potential for personal growth is high but so is the potential for failure. If people successfully deal with the conflict, they emerge from the stage with psychological strengths that will serve them well for the rest of their lives. If they fail to deal effectively with these conflicts, they may not develop the essential skills needed for a strong sense of self. Mastery Leads to Ego Strength Erikson also believed that a sense of competence motivates behaviors and actions. Each stage in Erikson's theory is concerned with becoming competent in an area of life. Overview of Erikson's Stages of Development So what exactly did Erikson's theory of psychosocial development entail? Much like Sigmund Freud, Erikson believed that personality developed in a series of stages. Unlike Freud's theory of psychosexual stages, however, Erikson's theory described the impact of social experience across the whole lifespan. Erikson was interested in how social interaction and relationships played a role in the development and growth of human beings. Erikson's theory was based on what is known as the epigenetic principle. This principle suggests that people grow in a sequence that occurs over time and in the context of a larger community. Conflict During Each Stage Each stage in Erikson's theory builds on the preceding stages and paves the way for following periods of development. In each stage, Erikson believed people experience a If the stage is handled well, the person will feel a sense of mastery, which is sometimes referred to as ego strength or ego quality. If the stage is managed poorly, the person will emerge with a sense of inadequacy in that aspect of development. Stage 1: Trust vs. Mistrust The first stage of Erikson's theory of psychosocial development occurs between birth and 1 year of age and is the most fundamental stage in life. Because an infant is utterly dependent, developing trust is based on the dependability and quality of the child's caregivers. At this point in development, the child is utterly dependent upon adult caregivers for everything they need to survive including food, love, warmth, safety, and nurturing. If a caregiver fails to provide adequate care and love, the child will come to feel that they cannot trust or depend upon the adults in their life. Outcomes If a child successfully develops trust, the child will feel safe and secure in the world.2 Caregivers who are inconsistent, emotionally unavailable, or rejecting contribute to feelings of mistrust in the children under their care. Failure to develop trust will result in fear and a belief that the world is inconsistent and unpredictable. During the first stage of psychosocial development, children develop a sense of trust when caregivers provide reliability, care, and affection. A lack of this will lead to mistrust. No child is going to develop a sense of 100% trust or 100% doubt. Erikson believed that successful development was all about striking a balance between the two opposing sides. When this happens, children acquire hope, which Erikson described as an openness to experience tempered by some wariness that danger may be present. developing a greater sense of personal control. The Role of Independence At this point in development, children are just starting to gain a little independence. They are starting to perform basic actions on their own and making simple decisions about what they prefer. By allowing kids to make choices and gain control, parents and caregivers can help children develop a sense of autonomy.2 Potty Training The essential theme of this stage is that children need to develop a sense of personal control over physical skills and a sense of independence. Potty training plays an important role in helping children develop this sense of autonomy. Like Freud, Erikson believed that toilet training was a vital part of this process. However, Erikson's reasoning was quite different than that of Freud's. Erikson believed that learning to control one's bodily functions leads to a feeling of control and a sense of independence. Other important events include gaining more control over food choices, toy preferences, and clothing selection. Outcomes Children who struggle and who are shamed for their accidents may be left without a sense of personal control. Success during this stage of psychosocial development leads to feelings of autonomy; failure results in feelings of shame and doubt. Subsequent work by researchers including John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth demonstrated the importance of trust in forming healthy attachments during childhood and adulthood. Finding Balance Children who successfully complete this stage feel secure and confident, while those who do not are left with a sense of inadequacy and self-doubt. Erikson believed that achieving a balance between autonomy and shame and doubt would lead to will, which is the belief that children can act with intention, within reason and limits. Stage 2: Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt The second stage of Erikson's theory of psychosocial development takes place during early childhood and is focused on children Stage 3: Initiative vs. Guilt The third stage of psychosocial development takes place during the preschool years. At this point in psychosocial development, children begin to assert their power and control over the world through directing play and other social interactions. Children who are successful at this stage feel capable and able to lead others. Those who fail to acquire these skills are left with a sense of guilt, self-doubt, and lack of initiative. Outcomes The major theme of the third stage of psychosocial development is that children need to begin asserting control and power over the environment. Success in this stage leads to a sense of purpose. Children who try to exert too much power experience disapproval, resulting in a sense of guilt. When an ideal balance of individual initiative and a willingness to work with others is achieved, the ego quality known as purpose emerges. Stage 4: Industry vs. Inferiority The fourth psychosocial stage takes place during the early school years from approximately ages 5 to 11. Through social interactions, children begin to develop a sense of pride in their accomplishments and abilities. Children need to cope with new social and academic demands. Success leads to a sense of competence, while failure results in feelings of inferiority. Outcomes Children who are encouraged and commended by parents and teachers develop a feeling of competence and belief in their skills. Those who receive little or no encouragement from parents, teachers, or peers will doubt their abilities to be successful. Successfully finding a balance at this stage of psychosocial development leads to the strength known as competence, in which children develop a belief in their abilities to handle the tasks set before them. Stage 5: Identity vs. Confusion The fifth psychosocial stage takes place during the often turbulent teenage years. This stage plays an essential role in developing a sense of personal identity which will continue to influence behavior and development for the rest of a person's life. Teens need to develop a sense of self and personal identity. Success leads to an ability to stay true to yourself, while failure leads to role confusion and a weak sense of self. During adolescence, children explore their independence and develop a sense of self.2 Those who receive proper encouragement and reinforcement through personal exploration will emerge from this stage with a strong sense of self and feelings of independence and control. Those who remain unsure of their beliefs and desires will feel insecure and confused about themselves and the future. What Is Identity? When psychologists talk about identity, they are referring to all of the beliefs, ideals, and values that help shape and guide a person's behavior. Completing this stage successfully leads to fidelity, which Erikson described as an ability to live by society's standards and expectations. While Erikson believed that each stage of psychosocial development was important, he placed a particular emphasis on the development of ego identity. Ego identity is the conscious sense of self that we develop through social interaction and becomes a central focus during the identity versus confusion stage of psychosocial development. According to Erikson, our ego identity constantly changes due to new experiences and information we acquire in our daily interactions with others. As we have new experiences, we also take on challenges that can help or hinder the development of identity. Why Identity Is Important Our personal identity gives each of us an integrated and cohesive sense of self that endures through our lives. Our sense of personal identity is shaped by our experiences and interactions with others, and it is this identity that helps guide our actions, beliefs, and behaviors as we age. Stage 6: Intimacy vs. Isolation Young adults need to form intimate, loving relationships with other people. Success leads to strong relationships, while failure results in loneliness and isolation. This stage covers the period of early adulthood when people are exploring personal relationships.2 Erikson believed it was vital that people develop close, committed relationships with other people. Those who are successful at this step will form relationships that are enduring and secure. Building On Earlier Stages Remember that each step builds on skills learned in previous steps. Erikson believed that a strong sense of personal identity was important for developing intimate relationships. Studies have demonstrated that those with a poor sense of self tend to have less committed relationships and are more likely to struggler with emotional isolation, loneliness, and depression. Successful resolution of this stage results in the virtue known as love. It is marked by the ability to form lasting, meaningful relationships with other people. Stage 7: Generativity vs. Stagnation Adults need to create or nurture things that will outlast them, often by having children or creating a positive change that benefits other people. Success leads to feelings of usefulness and accomplishment, while failure results in shallow involvement in the world. During adulthood, we continue to build our lives, focusing on our career and family. Those who are successful during this phase will feel that they are contributing to the world by being active in their home and community.2Those who fail to attain this skill will feel unproductive and uninvolved in the world. Care is the virtue achieved when this stage is handled successfully. Being proud of your accomplishments, watching your children grow into adults, and developing a sense of unity with your life partner are important accomplishments of this stage. Stage 8: Integrity vs. Despair The final psychosocial stage occurs during old age and is focused on reflecting back on life.2 At this point in development, people look back on the events of their lives and determine if they are happy with the life that they lived or if they regret the things they did or didn't do. Erikson's theory differed from many others because it addressed development throughout the entire lifespan, including old age. Older adults need to look back on life and feel a sense of fulfillment. Success at this stage leads to feelings of wisdom, while failure results in regret, bitterness, and despair. At this stage, people reflect back on the events of their lives and take stock. Those who look back on a life they feel was well-lived will feel satisfied and ready to face the end of their lives with a sense of peace. Those who look back and only feel regret will instead feel fearful that their lives will end without accomplishing the things they feel they should have. Outcomes Those who are unsuccessful during this stage will feel that their life has been wasted and may experience many regrets. The person will be left with feelings of bitterness and despair. Those who feel proud of their accomplishments will feel a sense of integrity. Successfully completing this phase means looking back with few regrets and a general feeling of satisfaction. These individuals will attain wisdom, even when confronting death. Strengths and Weaknesses of Erikson's Theory Erikson's theory also has its limitations and attracts valid criticisms. What kinds of experiences are necessary to successfully complete each stage? How does a person move from one stage to the next? Criticism One major weakness of psychosocial theory is that the exact mechanisms for resolving conflicts and moving from one stage to the next are not well described or developed. The theory fails to detail exactly what type of experiences are necessary at each stage in order to successfully resolve the conflicts and move to the next stage. Support One of the strengths of psychosocial theory is that it provides a broad framework from which to view development throughout the entire lifespan. It also allows us to emphasize the social nature of human beings and the important influence that social relationships have on development. Researchers have found evidence supporting Erikson's ideas about identity and have further identified different sub-stages of identity formation.4Some research also suggests that people who form strong personal identities during adolescence are better capable of forming intimate relationships during early adulthood. Other research suggests, however, that identity formation and development continues well into adulthood.5 Why Was Erikson's Theory Important? The theory was significant because it addressed development throughout a person's life, not just during childhood. It also stressed the importance of social relationships in shaping personality and growth at each point in development. Understanding Psychosocial Development Psychosocial development describes how a person's personality develops, and how social skills are learned from infancy through adulthood. In the 1950s, psychologist Erik Erikson published his theory about the eight stages of psychosocial development. Erikson believed that during each stage, a person experiences a "psychosocial crisis" that either has a positive or negative effect on that person's personality. The Principles of Psychosocial Development According to Erikson, an individual's personality and social skills develop in eight stages, which cover the entire life span. At each stage, a person is faced with a psychosocial crisis—critical issues—that need to be resolved. The person's personality is shaped by the way they respond to each of these crises. If they react positively, a new virtue (moral behavior) is gained. The Stages of Psychosocial Development The eight stages of psychosocial development are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Trust vs. Mistrust Autonomy vs. Shame Initiative vs. Guilt Industry vs. Inferiority Identity vs. Role Confusion Intimacy vs. Isolation Generativity vs. Stagnation Ego Integrity vs. Despair Stage 1: Trust vs. Mistrust The first stage of Erikson's theory of psychosocial development, trust vs. mistrust, begins at birth and lasts until around 18 months of age. During this stage, the infant is completely dependent on their caregiver to meet their needs. With consistent care, the infant learns to trust and feel secure. The virtue gained in this stage is "hope." Success in stage 1 helps a person be able to trust others in future relationships, as well as trust in their own ability to deal with challenging situations later in life. When an infant's needs aren't met in this stage, they can become anxious and untrusting. Stage 2: Autonomy vs. Shame Stage 2, autonomy vs. shame, occurs from 18 months to around 3 years of age. During this stage, children's physical skills grow while they explore their environment and learn to be more independent. Children react positively during stage 2 when caregivers allow them to work on developing independence within a safe environment. The virtue gained in this stage is "will." If the child is overly criticized or lives in a controlling environment, they can feel shame and doubt their abilities to take care of themselves.3 Stage 2 Skills Examples of skills learned in stage 2 of Erikson's theory of psychosocial development include potty training, getting dressed, and brushing teeth. This stage also includes physical skills such as running and jumping. Stage 3: Initiative vs. Guilt Stage 3, initiative vs. guilt, occurs during the early school-age years of a child's life. During this stage, a child learns to initiate social interactions and play activities with other children. Children also ask lots of questions in this stage. If the child is overly-controlled or made to feel that their questions are annoying, the child can develop feelings of guilt. However, when a child is successful in this stage, the virtue gained is a sense of "purpose."3 Stage 4: Industry vs. Inferiority Stage 4 of Erikson's theory of psychosocial development typically occurs between the ages of 5 and 12 years. The psychosocial crisis in this stage is industry vs. inferiority. During this stage, a child is learning how to read and write. Children in this stage also put a higher amount of importance on what their peers think about them, and start to take pride in their accomplishments. The virtue gained when a child is successful in stage 4 is "competence." If a child responds negatively to this psychosocial crisis, it can lead to feelings of inferiority and low self-esteem. Personality: Erikson vs. Freud While Erikson believed that personality is developed throughout the life span, neurologist Sigmund Freud based his theories of personality development on the belief that an adult's personality is primarily determined by early childhood experiences. Stage 5: Identity vs. Confusion Stage 5 occurs during the teenage years, between the ages of 12 to 18. At this stage, the psychosocial crisis is identity vs. confusion. During stage 5, teens are trying to "find themselves" and are searching for a sense of identity. The virtue that can be gained in stage 5 is "fidelity," or faithfulness. In stage 5, teens also learn how to accept other people who are different than themselves. According to Erikson, if a person responds negatively to the crisis in stage 5, it can lead to role confusion—uncertainty about themselves and how they fit into society.3 Stage 6: Intimacy vs. Isolation The psychosocial crisis in stage 6, intimacy vs. isolation, occurs in young adulthood (ages 18 to 40 years). The main focus in this stage is developing intimate relationships, and the virtue to be gained is "love." People who are not successful in stage 6 can feel alone and isolated. In some cases, this can lead to depression. Stage 7: Generativity vs. Stagnation Erikson's seventh level of psychosocial development occurs during middle age—between 40 to 65 years of age. The crisis at this stage is generativity vs. stagnation. Generativity is a person's way of "leaving a mark" on the world by giving back to society. This can include mentoring the younger generation, being successful at work, and positively impacting the community. The virtue that can be gained in stage 7 is "care." When a person is not successful in stage 7, it leads to stagnation. This can cause the person to feel useless and disconnected from their community. Stage 8: Integrity vs. Despair The final stage in Erikson's psychosocial theory of development is integrity vs. despair. This stage begins around age 65 years and continues for the remainder of a person's life. During this stage, a person reflects on their life and their accomplishments and comes to terms with the fact that death is unavoidable. According to Erikson, if a person does not feel their life was productive, or if a person has guilt over things that occurred in the past, it can lead to feelings of despair. If a person is successful in stage 8, the virtue to be gained is "wisdom." It is common for people in stage 8 to experience alternating periods of integrity and despair. The ultimate goal is to achieve balance. According to this Jean Piaget theory, children are not capable of performing certain tasks or understanding certain concepts until they reach a particular Piaget stage. In addition, Piaget believed that children move from one stage to the next after extensive exposure to relevant stimuli and experiences. With these experiences, both physical and cognitive, they are ready to master new skills, which are essential for children to move through the Piaget stages. The Four Jean Piaget Stages of Development Criticisms of Erikson's Theory There are several criticisms of Erikson's psychosocial theory of development. Some critics believe that Erikson was too focused on the idea that these stages need to be completed sequentially, and only occur in the age ranges he suggests. Other critics point out that Erikson used the European or American "male experience" as a template for all humans when he designed his stages of development.5 In addition, Erikson does not provide information about what types of experiences have to occur for a person to be successful in resolving the psychosocial crises at each stage of development. The Jean Piaget Stages of Cognitive Development In the 1960s and 1970s, as Freudian and Jungian psychology were rapidly being replaced by more empirical methods of studying human behavior, a Swiss philosopher and psychologist named Jean Piaget (1896-1980) offered a new theory of cognitive development. The Jean Piaget theory of cognitive development suggests that regardless of culture, the cognitive development of children follows a predetermined order of stages, which are widely known as the Jean Piaget stages of cognitive development. Sensorimotor Stage Age Range: Birth to 2 years old According to the Piaget theory, children like to explore at the sensorimotor stage. They want to watch, hear, taste, touch things around them. They learn about their environment by sensation: watching, grasping, sucking and manipulating objects they can get their eyes and hands on. They generally don’t appear to be thinking about what they do. As infants become toddlers, children enjoy their rapidly improving abilities to move around and take in new experiences. They focus on making sense of the world by linking their experiences to their actions. Piaget further divided the sensorimotor stage into six substages, each sighted with at the establishment of a new skill. Reflexes (0 – 1 month): Understanding of environment is attained through reflexes such as sucking and crying. Primary Circular Reactions (1 – 4 months): New schemas and sensations are combined, allowing children to engage in pleasurable actions deliberately, such as sucking their thumb. Secondary Circular Reactions (4 – 8 months): Children are now aware that their actions influence their environment and purposefully perform actions in order to achieve desired results. For example, they push a key on a toy piano to make a sound. Coordination of Reactions (8 – 12 months): Children explore their environment and often imitate the behavior of others. Tertiary Circular Reactions – (12 – 18 months): Children begin to experiment and try out new behavior. Early Representational Thought (18 – 24 months): Children begin to recognize and appreciate symbols that represent objects or events. They use simple language to catalog objects, e.g. “doggie”, “horsey”. see. They can imagine people or objects that don’t exist (such as a lizard with wings) more readily than younger children, and they like to make up their own games. During the late sensorimotor stage, children begin to learn the concept of object permanence. In other words, they know that an object will continue to exist even if they can no longer see it. By the time they reach the concrete operational stage, children can understand much more complex abstract concepts, such as time, space, and quantity. They can apply these concepts to concrete situations, but they still have trouble thinking about them independently of those situations. The practical knowledge developed during the sensorimotor stage will form the basis for children’s ability to form mental representations of objects in later Piaget stages. Preoperational Stage Age Range: 2-7 years old At the preoperational stage, children understand object permanence very well. However, they still don’t get the concept of conservation. They don’t understand that changing an object’s appearance doesn’t change its properties or quantity. In the experiment, Piaget poured the exact same amount of water into two identical glasses and asked the children whether the glasses contained the same amount of water. The children said that both glasses contained the same amount of water. Piaget then poured the water in one glass into a tall, narrow beaker and repeated the question. This time, the children said there was more water in the cylinder because it was taller. Concrete Operational Stage Age Range: 7-11 years old Piaget pointed out that at this stage, children’s ideas about time and space are sometimes inconsistent. They can learn rules fairly easily, but they may have trouble understanding the logical implications of those rules in unusual situations. Around age two, children enter what Piaget called the preoperational stage where they learn how to think abstractly, understand symbolic concepts, and use language in more sophisticated ways. They learn to use words to describe people, their feelings and their environments. In addition, at the concrete operational stage, children are able to use inductive logic – the type of reasoning that starts from a specific idea and leads to a generalization. They can also distinguish facts from fantasies, as well as formulate judgements about cause and effect. Now that children can express themselves better, they become insatiably curious and begin to ask questions about everything they Another important child development milestone at this stage is the idea of reversibility – children understand that some objects can be altered and then shaped back to their original shape. For example, a deflated balloon can be filled with air again to become an inflated balloon. Formal Operational Stage Age Range: 11 years old and older At the final stage of the Jean Piaget stages of cognitive development, children are capable of more abstract, hypothetical, and theoretical reasoning. They are no longer bound to observable and physical events. They can approach and resolve problems systematically by formulating hypotheses and methodically testing them out. Children can now apply their reasoning to a variety of situations including counterfactual “if-then” situations, meaning in situations where the “if” is known to be untrue. For example “if dogs were reptiles, they would have cold blood.” They can accept this as valid reasoning, even though the premise is obviously false. As children grow older, formal logic becomes possible and verbal explanations of concepts are usually sufficient without demonstration. They can consider possible outcomes and consequences of their actions without actually performing them. In addition, strategy-based games become more enjoyable, whereas rote games like “chutes-and-ladders” become too repetitive and boring for them. The Jean Piaget theory of cognitive development has been the subject of some criticism over the years, particularly from cross-cultural psychologists who question whether the Piaget stages are unique to Western children. Regardless of the criticism, the Piaget theory has proven to be invaluable and formed the basis for a number of other famous psychological ideas, including Kohlberg’s theory of moral development. Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development Based on Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development, American psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg (1927-1987) developed his own theory of moral development in children. According to Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development, there are 6 stages of moral development, known as Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. One of Kohlberg’s best known experiments is known as the Heinz Dilemma. In this experiment, Kohlberg presented a story about a man named Heinz: Heinz’s wife had a form rare cancer and was dying. A doctor told Heinz that a local chemist had invented a new drug that might save his wife. Heinz was very happy to hear this and went to talk to the chemist. When Heinz saw the price tag of the new drug, he was devastated because there was no way he could afford the drug. Heinz also knew that the price was ten times of the cost of the drug so the chemist was making a big buck from this drug. Heinz tried his best to borrow money from his friends and family, but the money was still not enough. He went back to the chemist and begged the chemist to lower the price. The chemist refused to do that. Heniz knew that his wife would die without this new drug, so he broke into the chemist’s office that night and stole the drug. After telling Heinz’s story to children in various age groups, Kohlberg asked them what Heinz should do. Based on the children’s responses, Kohlberg classified their moral reasoning into three levels, each of which contains two distinct substages: Pre-conventional Level ● Obedience ● Self-interest Conventional Level ● Conformity ● Law and order Post-conventional Level ● Social contract orientation ● Universal human ethics Age ranges are considerably more vague in the Kohlberg’s stages than in the Piaget stages, as children vary quite significantly in their rate of moral development. The Pre-conventional Level The pre-conventional stage is associated with the first two Kohlberg’s stages of moral development: Obedience and Self-interest. At this level, children are only interested in securing their own benefits. This is their idea of morality. They begin by avoiding punishment, and quickly learn that they may secure other benefits by pleasing others. No other ethical concepts are available to children this young. When being asked what Heinz should do, children at this level of moral development may answer: ● He shouldn’t steal the drug because it’s bad to steal. ● He should steal the drug because the chemist is charging too much. ● He should steal the drug because he’ll feel good that he saves his wife. ● He shouldn’t steal the drug because he’ll end up in prison. These Kohlberg stages are parallel to Piaget’s sensorimotor stage – for children whose conceptual framework don’t extend beyond their own senses and movements, the moral concepts of right and wrong would be difficult to develop. The Conventional Level According to Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development, the conventional level is associated with Conformity and Law and Order. This is the stage at which children learn about rules and authority. They learn that there are certain “conventions” that govern how they should and should not behave, and learn to obey them. At this stage, no distinction is drawn between moral principles and legal principles. What is right is what is handed down by authority, and disobeying the rules is always by definition “bad.” When being asked what Heinz should do, children at this level of moral development may answer: ● He should steal the drug because he is a good husband, and a good husband would do anything to save his wife. ● He shouldn’t steal the drug because he’s not a criminal. ● He shouldn’t steal the drug because it’s illegal to steal. ● He should steal the drug to save his wife and after that, he should go to prison for the crime. Kohlberg believed that some people stay at this stage of moral reasoning for their whole lives, deriving moral principles from social or religious authority figures and never thinking about morality for themselves. The Post-conventional Level The post-conventional level is associated with these Kohlberg’s stages of moral development: Social contract orientation and Universal human ethics. At this level, children have learned that there is a difference between what is right and what is wrong from a moral perspective, and what is right and what is wrong according to rules. Although they often overlap, there are still times when breaking a rule is the right thing to do. When being asked what Heinz should do, children at this level of moral development may answer: ● He should steal the drug because everyone has a right to live, regardless of the law. ● He shouldn’t steal the drug because the chemist deserves to get paid for his effort to develop the drug. ● He should steal the drug because saving life is more important than anything else. ● He shouldn’t steal the drug because others also have to pay for the drug. It’s only fair that he pays for it as well. Comparisons of Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development and Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development Although Kohlberg’s stages of moral development aren’t direct parallels of Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, Kohlberg was inspired by Piaget’s work. By comparing these two theories, you can get a sense of how our concepts of the world around us (our descriptive concepts) influence our sense of what we ought to do in that world (our normative concepts). than others. This, of course, presupposes certain moral assumptions, and so from a philosophical perspective Kohlberg’s argument is circular. Furthermore, there are also some studies that indicate that children as young as six years old can attain vague concepts of universal ethical principles – they may be able to distinguish between a rule that says “no hitting” (universal and moral) and one that says “kids must sit in a circle during story-time” (conventional, arbitrary, and non-moral). Since Kohlberg’s theory of moral development questions whether even teenagers can attain this level of moral reasoning, these studies throw considerable doubt on his conclusions. The best conjecture, however, may be that Kohlberg’s stages of moral development describe not a one-way process of psychological growth for an individual, but a categorization of different types of moral values, which may be developed and prioritized differently for different individuals and moral cultures. What is the Havighurst Developmental Tasks Theory? Although many theorists are responsible for contributing to the Developmental Tasks Theory, it was Robert Havighurst who elaborated on this development theory in the most systematic and extensive manner. Criticisms of Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development Like Piaget, Kohlberg has come under fire in recent years from cross-cultural psychologists who believe that Kohlberg’s theory is simply a codification of Western (post-modern Western liberal, to be precise) notions of justice and morality. Other moral and political cultures may not believe in certain principles. These critics argue that Kohlberg’s stages of moral development are Kohlberg’s attempt to make his own moral beliefs appear to be psychological facts. Kohlberg’s theory of moral development also seems to have a troubling normative aspect – that is, it seems to suggest that certain kinds of moral reasoning are better The main assertion of the Havighurst developmental tasks theory is that development is continuous throughout a person’s entire lifespan, occurring in stages. A person moves from one stage to the next by means of successful resolution of problems or performance of certain developmental tasks. These tasks are typically encountered by most people in the culture where that person belongs. According to the Havighurst developmental tasks theory, when people successfully accomplish the developmental tasks at a stage, they feel pride and satisfaction. They also earn the approval of their community or society. This success provides a sound foundation that allows these people to accomplish the tasks that they will encounter at later Havighurst developmental stages. demonstrate maturation at a level that is most conducive to learning and successfully performing the developmental tasks at these stages. Conversely, when people fail to accomplish the developmental tasks at a stage, they’re often unhappy and are not accorded the desired approval by society. This results in the subsequent experience of difficulty when faced with succeeding developmental tasks at later Havighurst developmental stages. Psychological Influences Psychological factors that emerge from a person’s maturing personality and psyche are embodied in his/her personal values and goals. These values and goals are another source of some developmental tasks such as establishing one’s self-concept, developing relationships with peers of both sexes and adjusting to retirement or to the loss of a spouse. The Bio-Psychosocial Model of Development Robert Havighurst proposed a bio-psychosocial model of development. According to Havighurst’s Developmental Tasks Theory, the developmental tasks at each stage are influenced by a person’s biology (physiological maturation and genetic makeup), his/her psychology (personal values and goals), as well as his/her sociology (specific culture to which the individual belongs). Biological Influences Some Havighurst developmental tasks are evolved out of the biological characteristics of humans and are faced similarly by people of any culture. An example of this happens in child development – learning how to walk for infants. Being a skill that depends on maturation and genetically determined factors, the mechanics involved in learning how to walk are virtually the same and occur at generally the same time for children from all cultures. Other developmental tasks in child development that stem from biological mechanisms include learning to talk, exercising control over bodily functions, as well as learning skills typically utilized in children’s games, to name a few. Havighurst pointed out the importance of sensitive stages which he considered to be the ideal teachable moments during child development. At these stages, children Social Influences There are other developmental tasks that arise from the unique cultural standards of a given society. These tasks may be observed in different forms in varying societies or, alternatively, may be observed is some cultures but not in others. For example, someone who belongs to an agricultural community might make the preparations for an occupation such as becoming a farmer at an early age. Members of an industrialized society, on the other hand, require longer and more specialized preparation for an occupation. Therefore, they tend to embark on this developmental task later in life. Other culturally-based developmental tasks include achieving gender-appropriate roles and becoming a responsible citizen. The Havighurst Developmental Stages Robert Havighurst proposed a list of common critical developmental tasks, categorized into six stages of development. The table below shows a partial list of Havighurst developmental tasks. Lev Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development In early 20th century, a Russian psychologist named Lev Vygotsky developed a theory of cognitive development in children known as Lev Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development. The main assertion of the Vygotsky theory is that cognitive development in early childhood is advanced through social interaction with other people, particularly those who are more skilled. In other words, unlike Piaget’s theory, Vygotsky proposed that social learning comes before cognitive development in children, and that children construct knowledge actively. ● ● The child can receive instructions from the MKO during the learning process. The MKO can offer temporary support (scaffolding) to the child during the learning proces For example, a five-year-old child knows how to ride a tricycle, but can’t ride a bicycle (with two wheels) unless his grandfather holds onto the back of her bike. According to Vygotsky’s theory, this child is in the zone of proximal development for riding bicycle. With her grandfather’s help, this little girl learns to balance her bike. After some practising, she can ride the bike on her own. Vygotsky’s Concept of Zone of Proximal Development Lev Vygotsky is most recognized for his concept of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) pertaining to the cognitive development in children. Vygotsky’s concept of Zone of Proximal Development underscores Vygotsky’s conviction that social influences, particularly getting instructions from someone, are of immense importance on the cognitive development in early childhood. According to the Vygotsky theory of cognitive development, children who are in the zone of proximal development for a particular task can almost perform the task independently, but not quite there yet. With a little help from certain people, they’ll be able to perform the task successfully. According to Vygotsky’s theory, as children are given instructions or shown how to perform certain tasks, they organize the new information received in their existing mental schemas. They use this information as guides on how to perform these tasks and eventually learn to perform them independently. Vygotsky’s Concept of More Knowledgeable Other Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory emphasizes that children learn through social interaction that include collaborative and cooperative dialogue with someone who is more skilled in tasks they’re trying to learn. Vygotsky called these people with higher skill level the More Knowledgeable Other (MKO). MKO could be teachers, parents, tutors and even peers. Some factors that are essential in helping a child in the zone of proximal development: ● The presence of someone who has better skills in the task that the child is trying to learn. This “someone” is known as a “More Knowledgeable Other”(MKO), which we will discuss below. In our example of the five-year-old girl learning to ride a bike, her grandfather not only holds onto the back of the bike, but also verbally teaches her how to balance her bike. From the little girl’s point of view, her grandfather is what Vygotsky would call a More Knowledgeable Other. Vygotsky’s Concept of Scaffolding Vygotsky’s concept of scaffolding is closely related to the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development. Scaffolding refers to the temporary support given to a child by a More Knowledgeable Other that enables the child to perform a task until such time that the child can perform this task independently. According to the Vygotsky theory, scaffolding entails changing the quality and quantity of support provided to a child in the course of a teaching session. The MKO adjusts the level of guidance in order to fit the student’s current level of performance. For novel tasks, the MKO may utilize direct instruction. As the child gains more familiarity with the task and becomes more skilled at it, the MKO may then provide less guidance. To illustrate Vygotsky’s concept of scaffolding using our example of the five-year-old learning to ride a bike: The little girl’s grandfather (MKO) may begin by holding onto the back of her bike the whole time that she is on the bike. As the little girl gains more experience, her grandfather may release his hold intermittently. Eventually the girl’s grandfather only grabs the bike when he needs to correct her balance. When the girl finally masters the skill, her grandfather no longer needs to hold onto her bike anymore, and the scaffolds can be removed. A major contribution of Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development in children is the acknowledgement of the social component in both cognitive and psychosocial development. Due to Vygotsky’s proffered ideas, research attention has been shifted from the individual onto larger interactional units such as parent and child, teacher and student, brother and sister, etc. The Vygotsky theory also called attention to the variability of cultural realities, stating that the cognitive development of children who are in one culture or subculture, such as middle class Asian Americans, may be totally different from children who are from other cultures. Therefore, it would not be fitting to compare the developmental milestones of children from one culture to those of children from other cultures.