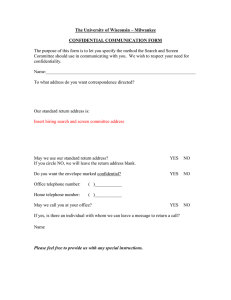

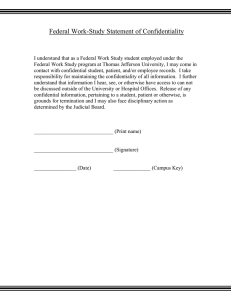

ARTICLE IN PRESS Just between Us: An Integrative Review of Confidential Care for Adolescents Stacy Baldridge, MSN, RN, CNRN, CCRC, & Lene Symes, PhD, RN ABSTRACT Introduction: Confidential care is recommended for all adolescents to facilitate risk behavior screening and discussion of sensitive topics. Only 40% of adolescents receive confidential care. The purpose of this integrative review is to describe research related to the practice of confidential care for adolescents. Evidence was analyzed to identify strategies to increase confidential care and improve risk behavior screening. Method: Whittemore and Knafl’s integrative literature review process was applied. Results: The 26 research articles included in this review included patients’, parents’, and physicians’ perspectives. Confidential care practice is inconsistent. Strategies to improve practice are known. Conclusions: Four key elements should be considered to establish a practice culture of confidential care for adolescents. Strategies for implementing the key elements of confidential care and supporting resources for efficient use of time alone are provided. J Pediatr Health Care. (2017) ■■, ■■-■■. KEY WORDS Adolescent, confidential, confidential care, risk behavior Stacy Baldridge, PhD Student, Texas Woman’s University, College of Nursing, Houston, TX. Lene Symes, Professor, Texas Woman’s University, College of Nursing, Houston, TX. Conflicts of interest: None to report. Correspondence: Stacy Baldridge, MSN, RN, CNRN, CCRC, College of Nursing, Texas Woman’s University, 6700 Fannin St., Houston, TX 77030-2897; e-mail: sbaldridge@twu.edu 0891-5245/$36.00 Copyright © 2017 by the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.09.009 www.jpedhc.org INTRODUCTION All adolescents should receive screening for risk behaviors and preventive counseling. In 2017, Laura Searcy, President of the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, called for education and universal screening for mental, behavioral, and substance use disorders (Searcy, 2017). Adolescent participation in risk-taking behaviors, such as smoking or drug use, is an established problem recognized by parents, consumers, and health care professionals (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2016; National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], National Institutes of Health [NIH], & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2017). Annual updates from the University of Michigan’s Monitoring the Future study with NIDA, NIH, and USDHHS make clear the extent of risk behaviors related to alcohol and drug use (Figure 1; National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). In 2015, 27.1 million people aged 12 years or older had used an illicit drug in the past 30 days, largely marijuana and prescription pain relievers (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016). If adolescents are afforded the opportunity for confidential conversations, risk behaviors are more likely to be disclosed (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2016). However, it is likely that only 40% of adolescents spent confidential time with providers during preventive care visits (Irwin, Adams, Park, & Newacheck, 2009). The proportion of adolescents with chronic diseases who receive confidential time may be even less. Nash, Britto, Lovell, Passo, and Rosenthal (1998) found that only 27% of adolescent rheumatology patients (N = 52; n = 14) had ever been interviewed alone. Adolescents with chronic medical conditions may participate in risk behaviors as much or more than their healthy peers (Miauton, Narring, & Michaud, 2003; ■■ 2017 1 ARTICLE IN PRESS MARIJUANA Nylander, Seidel, & Tindberg, 2014; Suris, Michaud, Akre, & Sawyer, 2008; Suris & Parera, 2005). Borowsky, Ireland, and Resnick (2009) studied the relationship of health status to risk behaviors over time in youths in the United States. They found that of 20,745 youth, 3,018 (14.5%) anticipated a high likelihood of early death. The possibility of early death was a risk factor for participation in health-jeopardizing behaviors. Suris and Parera (2005) found that despite the likelihood of more frequent contact with health care professionals for adolescents with chronic conditions, such contact may not be associated with a lower rate of risk behavior participation. Disease management is often the priority during clinic visits, but providers should consider the potential negative effects of risk behavior participation on the adolescent’s already compromised health (Louis-Jacques & Samples, 2011; Nylander et al., 2014). There is a need to understand the practice of confidential care as a potential facilitator of risk behavior screening and intervention. The purpose of this integrative review is to describe research related to the practice of confidential care for adolescents and to answer the following questions. • What is the current practice of confidential care? • What are the facilitators of and barriers to confidential care? • What is the perspective of parents and adolescents? • What strategies support confidential care for adolescents? BACKGROUND The Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services (2014) describes adolescent and provider time alone as potentially “the most effective way to help the adolescent develop engagement and autonomy on health-related issues as well as to improve delivery of guidance on sensitive 2 Volume ■■ • Number ■■ 12th Grade CIGARETTE 12.50% 11.00% 6.20% 4.90% 2.60% 10.50% 14.00% 5.40% 7.30% ALCOHOL 10th Grade 22.50% 8th Grade 19.90% 33.20% FIGURE 1. Past month use of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes of 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students (National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). E-CIGARETTE topics” (p. 10). The There is a need to American Academy of understand the Pediatrics (2016) in the practice of Bright Futures guidelines recommend that confidential care as providers spend time a potential alone with children as facilitator of risk young as 11 years during well-care visits. behavior screening The American Medical and intervention. Association’s (1997) Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services recommends time alone with adolescents during preventive care. The Society for Adolescent Medicine recommends that providers regularly spend part of each visit alone with patients, beginning when they are in early adolescence (Ford, English, & Sigman, 2004). Despite these recommendations, Irwin et al. (2009) found that only 40% of adolescents (N = 3,038) had time alone with the provider at their most recent preventive care visit. Adolescents with chronic medical conditions are likely to have relatively frequent visits with health care professionals, but parents are likely to be present during the visit, which may inhibit confidential conversations between the provider and adolescent (Suris et al., 2008). Britto, Rosenthal, Taylor, and Passo (2000) evaluated pediatric rheumatologists’ screening for risk behaviors (n = 10 physicians and n = 178 patients) and found that most patients were not screened for risk behaviors before an educational intervention to improve screening rates that were very low: fewer than 5% for alcohol, smoking, and marijuana and 12% for sexual activity. The physicians described limited opportunities for confidential discussions. In an earlier report, Britto et al. (1999) concluded that the parents of adolescents with chronic conditions might be unlikely Journal of Pediatric Health Care ARTICLE IN PRESS to leave adolescents alone with the physician during a visit. Primary care providers also described parental involvement as a barrier to substance abuse screening when parents refuse to leave the room (van Hook et al., 2007). Limited time for visits was also described as a barrier to provision of time alone (Britto et al., 2000; McKee, Rubin, Campos, & O’Sullivan, 2011). Clinician time alone with adolescents facilitates open and honest conversations and fosters a confidential relationship to allow discussion of sensitive topics (Ford et al., 2004). In addition to aiding discussion of sensitive topics, confidential care is also a factor in adolescent decision-making to seek medical care. Adolescents in the United States who forgo medical care because of concerns with confidentiality are a population at risk and are likely in need of health care services (Lehrer, Pantell, Tebb, & Shafer, 2007). The effect of confidential care extends beyond the immediate value of the interaction between provider and patient to potentially reduce negative outcomes related to high-risk behaviors and forgone medical care. METHODS The integrative literature review process described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) was followed for this review. EBSCOHost (all databases, including CINAHL and MEDLINE) and Scopus electronic databases were queried for combinations of search terms of confidential care, confidential, and adolescent. Additional publications were identified through ancestry search methods used during the review of previously identified articles. No limitations were placed on country or publication date. Inclusion criteria were reports of primary studies regarding practice of confidential care (specifically time alone) and reports of research related to patient, provider, or parent perspectives regarding confidential care or time alone with patients. Exclusion criteria were reports of studies focused on confidentiality of medical records and studies detailing gynecologic physical examinations or abortions. Although there may be value to understanding the practice of confidential visits for the purposes of gynecologic examinations or abortions, those practices are beyond the scope of this review. State laws and professional society recommendations guide practice for confidential care of adolescents considering abortion (Braverman et al., 2017). During the literature search phase, abstracts were reviewed for evaluation of inclusion/ exclusion criteria. Articles meeting inclusion criteria were retrieved for full-text review. Data collection and evaluation considerations of selected studies included review of the following criteria: sample population perspective (patient/parent/provider), research method, study purpose, data collection and analysis, study conclusions, reference to professional guideline or tool, mention of communication strategy or framework, themes, facilitators or barriers, and limitations. www.jpedhc.org The data analysis process followed Whittemore and Knafl’s (2005) steps of data reduction, display, comparison, and drawing conclusions. A table of study characteristics was developed, highlighting categories described in the data evaluation phase, such as purpose, research method, population, variables, results, and common themes. Quantitative and qualitative studies were categorized and analyzed based on the study population, noting patient, provider, and parent perspectives. Facilitators and barriers to confidential care were highlighted, as were themes that emerged from the analysis. Results are presented through a descriptive synthesis approach because of the inclusion of studies incorporating various research methods (Connelly, 2009). Evidence was evaluated using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Research Evidence Appraisal (Newhouse, Dearholt, Poe, Pugh, & White, 2007). The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice includes evidence ratings for the strength of research evidence (Levels I-V) and for the quality of evidence (Grades A, B, and C; Newhouse et al., 2007). RESULTS The initial search identified 507 articles. Titles and abstracts were reviewed for inclusion/exclusion criteria, and 59 articles were identified for full-text and ancestry review. Of those, 26 articles met the inclusion criteria for this integrative review (Figure 2). Publications meeting inclusion criteria included quantitative (n = 18), qualitative (n = 6), and mixed methods research reports (n = 2). The excluded publications included studies that did not describe time alone, editorials, review articles, position statements, or reports describing legal implications and practice without research findings. Most quantitative studies were conducted using survey methods. One study used a randomized-controlled research design. Study populations represented the perspectives of adolescent patients, parents, and physicians, and combinations (Table 1). Most qualitative studies were conducted with focus groups of parents and/or adolescents. The mixed methods study evaluated physician practice and experience (McKee et al., 2011; O’Sullivan, McKee, Rubin, & Campos, 2010). Studies were synthesized and categorized to address the questions posed for this review. Studies included in this review were evaluated as having Levels I through III strength of evidence, with quality ratings of A or B. No studies were excluded based on quality, because each showed value in answering questions relevant to this review. All selected articles described studies conducted in outpatient settings, with provider specialties including pediatrics, adolescent medicine, and family practice. Studies were conducted in the United States, New Zealand, and Australia. Publication dates ranged ■■ 2017 3 ARTICLE IN PRESS FIGURE 2. Literature review process. from 1985 through 2017. A summary table of articles is presented in Table 1, organized by perspectives of patients, parents, and providers. Review of Practice of Confidential Care Ten studies provided frequency rates of clinician time alone with patients, with most data based on recall by providers, patients, or parents. Two U.S. studies analyzed data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to review preventive care visits and time alone with providers (Edman, Adams, Park, & Irwin, 2010; Irwin et al., 2009). Providers recalled that 34% to 40% of adolescents who had a preventive care visit in the prior year had time alone with the clinician. Age was significantly correlated with time alone with the provider, and time alone was more likely during a preventive care visit than other types of visits (Edman et al., 2010). For patients who were not afforded time alone, authors noted the improbability of screening in the sensitive areas of sexual health or substance abuse (Irwin et al., 2009). Adolescent reports of time alone with providers to receive confidential, private health care varied. In a sample of New Zealand students in grades 8 through 12 (N = 9,107), 27% (n = 1,946) reported time alone with a provider (Denny et al., 2012). U.S. studies showed higher rates of time alone with a provider. In a nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents (5th12th grade, N = 6,748), 58% reported time alone with their provider (Klein, Wilson, McNulty, Kapphahn, & Collins, 1999). Gilbert, Rickert, and Aalsma (2014) surveyed parents (n = 500) and adolescent patients (n = 504). Approximately half of adolescent parents (n = 245) and fewer than half of adolescent patients (n = 199) reported that the adolescent had some time alone with a provider at the most recent visit. Across studies, females and older adolescents were consistently more likely to report time alone with the provider 4 Volume ■■ • Number ■■ (Denny et al., 2012; Gilbert et al., 2014; Klein et al., 1999). In a survey of pediatricians, internists, and family practice specialists (n = 1,630), 52% reported consistently spending some time alone with adolescent patients (Purcell, Hergenroeder, Kozinetz, Smith, & Hill, 1997). In a study of U.S. pediatric nephrologists (n = 66), 56% reported routinely (over 90% of the time) interviewing teens alone (Hergenroeder & Brewer, 2001). Respondents who interviewed patients alone were more likely to report assessing sexual history. A similar relationship between time alone and assessment of sexual history was found in a study of primary care physicians (n = 21). Of 144 visits that a parent attended, physicians reported that 68% of visits included time alone with the adolescent (O’Sullivan et al., 2010). Time alone was significantly more likely to be reported for patients receiving physical examinations and with a sexual complaint. Overall, physician providers reported providing confidential care for over half of adolescent visits. Similar results were found when researchers analyzed the transcripts of 49 pediatric and family practice physicians’ interactions with 166 overweight adolescents during annual visits (Bravender et al., 2014). Time alone was provided in approximately half of the visits (n = 85). Physicians providing assurances of confidentiality were more likely to provide time alone, and pediatricians offered time alone more frequently than family practice physicians. Specific statements of confidentiality were provided in approximately 31% of visits (Bravender et al., 2014). The University of Michigan implemented a quality improvement project to improve delivery of confidential care and risk behavior screening. Participating physicians (n = 44) reviewed charts for provision of confidential care and subsequently implemented quality improvement strategies to address barriers and change practice. The baseline rate of time alone with patients Journal of Pediatric Health Care www.jpedhc.org TABLE 1. Table of evidence Perspective Authors Research method N Significant findings Only 27% (n = 1,946) of students who had accessed care in the previous year reported confidential, private health care, which was more common among females and more common for older adolescents. Older adolescents noted preference of confidentiality of information, noting the risk of forgone care to avoid disclosure of information. Level III-A 1,123 boys, 1,315 girls Adolescents who forgo care because of confidentiality concerns are at risk and likely in greater need of health care services. Level III-B 6,728 adolescents Discussion of risks was more likely with adolescents who had time alone with providers. For adolescents reporting risk behaviors, most had not discussed them with providers. 58% of adolescents reported time alone with their provider; time alone was more frequent for females and for older adolescents. Adolescents missed care in efforts to hide information from their parents. Confidentiality assurances influenced adolescent willingness to disclose sensitive information and probability of future visits. Provider qualities of confidentiality and honesty ranked higher than medical knowledge for adolescents. Most adolescents noted that providers lacked in ensuring confidentiality, but parents reported that providers possessed the characteristic. Some adolescents reported lack of trust and withholding information from providers. Level III-B Adolescents Denny et al. (2012) Quantitative To determine the prevalence of health care use and private and confidential health care among a nationally representative population of high school students 9,107 adolescents Adolescents Britto et al. (2010) Qualitative 54 adolescents Adolescents Lehrer et al. (2007) Quantitative Adolescents Klein and Wilson (2002) Quantitative Adolescents Klein et al. (1999) only Quantitative To understand adolescents’ preferences for multidimensional aspects of privacy, including psychological, social, and physical, and confidentiality (informational privacy) in the health care setting To examine risk characteristics associated with citing confidentiality concern as a reason for forgoing health care among a sample of U.S. adolescents who reported having forgone health care they believed was necessary in the past year To compare adolescents’ reports of topics they wanted to discuss with providers with what was actually discussed and whether they talked about self-reported health risks To examine factors associated with access to care among adolescents, including gender, insurance coverage, and having a regular source of health care Adolescents Ford et al. (1997) Quantitative 562 adolescents Adolescents/parents Farrant and Watson (2004) Quantitative To investigate the influence of physicians’ assurances of confidentiality on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information and seek future health care To identify and compare perceptions of health care service delivery held by young people with chronic illness and their parents 6,748 adolescents 53 adolescent patients, 45 parents Evidence grade Level III-B Level III-A Level I-B Level III-B 5 (Continued on page 6) ARTICLE IN PRESS ■■ 2017 Purpose 6 TABLE 1. Continued. Volume ■■ • Number ■■ Perspective Authors Research method Gilbert et al. (2014) Quantitative Adolescents/parents McKee et al. (2006) Qualitative Adolescents/parents Rubin et al. (2010) Qualitative Parents Dempsey et al. (2009) Parents Purpose N Significant findings Evidence grade Journal of Pediatric Health Care To better understand how confidentiality affects the delivery of preventive adolescent health care by examining adolescent and parent beliefs and the relationship between confidentiality and the number and subject matter of health topics discussed at the last visit To obtain perspectives of mothers and daughters on facilitators of and barriers to adolescent girls’ timely access to riskappropriate reproductive care To obtain the perspectives of adolescent males and their mothers about the health care concerns of the adolescents and provision of confidential care 504 adolescents, 500 parents Approximately half of parents and patients reported confidential care. The split visit model supports the greatest mean number of topics discussed. Level III-A 22 mothers, 18 daughters Level III-B Quantitative To understand parental opinions about which topics should be discussed during adolescent preventive health visits and how best to incorporate adolescent confidentiality into these visits 1,025 parents Duncan et al. (2014) Quantitative 106 parents Parents Duncan et al. (2011) Quantitative Parents Edman et al. (2010) Quantitative To better understand how tensions (between guidance about adolescentfriendly care and parental involvement impact to Type 1 diabetes mellitus [T1DM] control) are reconciled in clinical practice by identifying how frequently adolescents with T1DM are seen alone and exploring parents’opinions about this. To document parental views regarding confidentiality with adolescents, aiming to identify topics that parents believe they should be informed about despite an assurance of confidentiality between their child and the doctor and to document harms and benefits that parents associate with adolescents seeing doctors alone To examine rates of time alone with any type of visit and preventive visit rates/ differences by age, gender Mothers described their role as protector and distrust of confidential care. Daughters worried about violations of confidentiality. Adolescents verbalized distrust of the process of confidential care. Mothers of sons supported confidential care but described feeling excluded. Adolescent males described distrust of the provider and concerns with confidentiality of information. Highlights disparity between parental desire to be informed and confidentiality: 66% of parents noted the importance of adolescent time alone with provider, but almost half preferred full disclosure of adolescents’ health information. 13% of parents reported adolescent time alone with physician. Concerns with time alone included not being informed of important information or treatment plan. 3 groups with mothers (n = 22), 2 groups with sons (n = 20) Level III-B Level III-B Level III-B 86 parents Parents’ primary concern with confidential care is a fear of not being informed about important information. Researchers describe disparity between parental desire to be informed and confidentiality laws and expectations. Level III-B 4,302 parents/ caregivers 34% of adolescents had time alone with provider. Time alone was more likely to occur during a preventive care visit and more likely for older adolescents. Level III-A (Continued on page 7) ARTICLE IN PRESS Adolescents/parents www.jpedhc.org TABLE 1. Continued. Perspective Authors Research method Purpose N Hutchinson and Stafford (2005) Quantitative To explore the prevalence of parents who have negative attitudes about teen privacy and whether education can influence a parent’s attitudes 188 parents Parents Irwin et al. (2009) Quantitative 8,464 adolescents Parents Sasse et al. (2013) Qualitative To examine receipt of preventive services, including disparities in services received, by using a nationally representative sample of adolescents To investigate the beliefs and opinions of parents about confidential care for adolescents Parents Tebb et al. (2012) Qualitative 52 parents Provider Bravender et al. (2014) Quantitative Provider Hergenroeder and Brewer (2001) Quantitative Provider Purcell et al. (1997) Quantitative Provider McKee, Rubin, Campos, & O’Sullivan (2011) Mixed methods (report of qualitative) To explore the knowledge and attitudes that Latino parents have about confidential health services for their teens and to identify factors that may influence those attitudes Objective examination of how often confidentiality is ensured, how often adolescents are seen alone, and which physicians are more likely to do either To determine pediatric nephrologists’ practices of sexual history taking and diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections in their adolescent patients To describe primary care physicians’ practices with regard to inviting parent(s) to leave the room to interview the teen alone, and the factors associated with use of this technique To describe primary care clinicians’ patterns of delivering time alone, decision making about introducing time alone to adolescents/parents, and experiences delivering confidential services Evidence grade Approximately half of parents believed that doctors should speak with teens alone; approximately 90% believed that teens should be able to have time alone if interested. The percentage of parents disagreeing with confidential care decreased after the educational intervention. 40% met with doctor alone; it is unlikely that screening or counseling related to sensitive topics took place. Level III-B Parental role and trust in provider inform opinions about confidentiality. There was a disparity between parent preference for information and confidentiality guidelines for providers. Wide range of knowledge of confidential care, trust in clinician is critical. Parents note desire to be informed. Level III-B Half of visits included time alone with adolescents. Explicit statements of confidentiality were provided in 31% of visits. Only 56% reported routine time alone with adolescents; 55% consistently asked females about sexual intercourse. Level III-B 1,630 physicians Only 52% of providers almost always/ always spent some time alone with adolescent patients Level III-B 20 physicians (18 interviews) Physicians describe time constraints as a barrier to time alone. Scripts facilitate time alone to include normative statements and purpose of confidential care. Level III-B 17 parents 45 physicians 66 nephrologists Level III-A Level III-B Level III-B 7 (Continued on page 8) ARTICLE IN PRESS ■■ 2017 Parents Significant findings 8 Volume ■■ • Number ■■ TABLE 1. Continued. Perspective Authors Research method Purpose Significant findings Providers reported that 68% of visits where a parent attended included time alone with the adolescent (out of 144 visits). Provision of time alone was significantly higher for visits with physical examinations and slightly higher for teens presenting with sex complaints. Interventions led to increase in provision of time alone, effective practice change, and improved confidential care. Level III-B Half of providers often/always provide opportunities for time alone (half sometimes/seldom/never), with a larger proportion of physicians reporting often/ always. Lack of time was the most common barrier to substance abuse screening; some noted parents refusing to leave adolescent alone as a barrier. Level III Provider O’Sullivan et al. (2010) Mixed methods (report of quantitative) To track primary care physicians’ time alone with adolescent patients and to identify key factors associated with its provision 21 providers Provider Riley, Ahmed, Lane, Reed, & Locke (2017) Quantitative 54 physicians Provider Wadman et al. (2014) Quantitative Provider van Hook et al. (2007) Qualitative To assess whether a medical board Maintenance of Certification Part IV project could improve the delivery of confidential care to minor adolescent patients seen in outpatient primary care practices To investigate the knowledge and practice of health care providers at Alberta Children’s Hospital and to inform practice about the adolescent’s right to confidentiality To identify barriers to adolescent substance abuse screening in primary care 389 providers 38 physicians Evidence grade Level III-B Level III-B ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Pediatric Health Care N ARTICLE IN PRESS was 77.3% (n = 706), and postintervention rates increased to 89.2% and 90.3% after two rounds of practice intervention with associated increases in risk behavior screening throughout the project (Riley, Ahmed, Lane, Reed, & Locke, 2017). In sum, the provision of time alone was more likely for older adolescents or female patients, or when visits were for preventive care, physical examinations, or evaluation of a sexual complaint. Significant numbers of adolescents are not afforded time alone with providers, which may represent a missed opportunity for risk behavior screening. An intervention designed to increase time alone was effective but still resulted in fewer than 100% of adolescents having time alone with physician providers during visits. To fully explore the practice of confidential care, an understanding of facilitators and barriers to the practice is necessary. Both are presented below, with consideration given to the perspectives of adolescents and their parents. Finally, strategies to improve confidential care are presented with evidence-based practice improvement techniques. Establishment of Trust Facilitates Confidential Care Trust between adolescent patient and provider, adolescent and parent, and parent and provider were common themes in nine studies of confidential care. A trusting relationship is developed when provider communication is honest and confidentiality is maintained. Adolescents and parents hold these provider qualities in high regard (Farrant & Watson, 2004). In a survey of adolescent diabetic patients and their parents (n = 53 patients, n = 45 parents), both ranked honesty higher than medical knowledge as desirable provider qualities. Adolescents also ranked confidentiality higher than medical knowledge. Compared with parents, fewer adolescents reported that specialty providers possessed qualities of honesty and maintaining confidentiality (Farrant & Watson, 2004). When adolescents have concerns about confidentiality, they may lie about behaviors, avoid discussing sensitive topics, or forgo health care altogether (Gilbert et al., 2014; Klein & Wilson, 2002; Lehrer et al., 2007; Rubin, McKee, Campos, & O’Sullivan, 2010). Adolescents are more willing to discuss sensitive topics when they are assured of confidentiality (Bravender et al., 2014; Ford, Millstein, Halpern-Felsher, & Irwin, 1997; Klein & Wilson, 2002). The only randomized controlled trial included in this review evaluated the impact of confidentiality assurances on adolescents’ willingness to share health information or to seek health care. Findings were based on the adolescents’ responses to audio portrayals of a physician introduction (Ford et al., 1997). Assurances of confidentiality influenced both adolescents’ willingness to disclose sensitive information (substance use, sexuality) and their probability of seeking health care in the future (Ford et al., 1997). The prowww.jpedhc.org vision of confidential care establishes an environment of trust that allows the adolescent an opportunity to discuss risk behaviors they may not willingly share in front of their parents (Klein & Wilson, 2002). Adolescents who reported poor communication with parents were more likely than those who reported better communication to also report that confidentiality concerns were a barrier to seeking health care (Lehrer et al., 2007). Parents described trust in the provider as integral to accepting their adolescent child receiving confidential care (Sasse, Aroni, Sawyer, & Duncan, 2013; Tebb, Hernandez, Shafer, Chang, & Otero-Sabogal, 2012). Minority adolescent males (Rubin et al., 2010) and minority mothers of daughters verbalized distrust of the process of confidential care (McKee, O’Sullivan, & Weber, 2006). Mothers of daughters described their role as being to protect their daughters. Exclusion of mothers during confidential care of their daughters threatened that role, contributing to discomfort and distrust of providers (McKee et al., 2006). Although many mothers of sons described similar feelings of exclusion, overall they supported confidential care (Rubin et al., 2010). Adolescent males described distrust of the provider and concerns with confidentiality of information. Adolescent girls had similar fears, but they appreciated the need for confidential care. Parents frequently differ from their children in perceptions of provider trust and confidentiality, with adolescents showing an underlying distrust of health care providers (Farrant & Watson, 2004). Trust is both a facilitator of, and potential barrier to, confidential care and the discussion of sensitive topics. To engage in discussions about sensitive issues, adolescents need providers to provide explicit assurances of confidentiality. Providers should consider the perspectives of both adolescents and parents when planning and carrying out confidential care. Parents Support Confidential Care but Want to be Fully Informed Findings from eight To engage in studies indicate that the discussions about three-way relationship sensitive issues, between parent, patient, and provider often adolescents need complicates confidenproviders to tial care for adolescents. provide explicit McKee et al. (2011) reported that tensions assurances of resulting from the threeconfidentiality. way relationships may affect delivery of confidential care when physicians try to honor those complex relationships. Parents may appreciate the value of confidential care yet a concurrent desire to be informed about everything that is discussed during the visit, thereby negating the visit’s value (Dempsey, Singer, ■■ 2017 9 ARTICLE IN PRESS Clark, & Davis, 2009; Duncan, Jekel, O’Connell, Sanci, & Sawyer, 2014; Duncan, Vandeleur, Derks, & Sawyer, 2011; Gilbert et al., 2014; Tebb et al., 2012). Awareness of the discrepancy between adolescents and their parents’ values, perceptions of confidential care, and trust of providers is important when planning and delivering confidential care (Farrant & Watson, 2004). Parental negative opinions about adolescent confidential care were successfully reduced using an education intervention in an adolescent medicine clinical setting (Hutchinson & Stafford, 2005). Adolescents with concerns about confidentiality may be at greater risk Adolescents consistently report concerns with confidentiality or parental notification as a primary reason to forgo health care (Britto, Tivorsak, & Slap, 2010; Ford et al., 1997; Klein et al., 1999; Lehrer et al., 2007). To further compound the problem, adolescents with concerns about confidentiality are often those with increased vulnerability because of risk behavior participation (Lehrer et al., 2007). Multiple studies have shown that adolescents who do access health care may lie about behaviors or may limit the topics of discussion, because they believe that their information will not remain confidential (Gilbert et al., 2014; Klein & Wilson, 2002; Rubin et al., 2010). Adolescents who are allowed to speak privately with the provider are more likely to discuss risk behaviors; they are also more likely to discuss a greater number of risk behaviors and to provide more detail about those behaviors (Gilbert et al., 2014; Klein & Wilson, 2002). Adolescents with confidentiality concerns place themselves at greater risk by avoiding health care or concealing the truth (Britto et al., 2010; Ford et al., 1997; Gilbert et al., 2014; Klein & Wilson, 2002; Klein et al., 1999; Lehrer et al., 2007; Rubin et al., 2010). Strategies to create a culture of confidential care Confidential care is frequently practiced in the context of preventive care, consistent with the focus of those visits on risk assessment and anticipatory guidance rather than an acute medical concern (Edman et al., 2010; Hutchinson & Stafford, 2005; O’Sullivan et al., 2010). Barriers to confidential care include parent and provider knowledge gaps, providers’ lack of comfort and lack of consistent practice, and process issues related to having time for confidential care during visits (Riley et al., 2017). Consistent practices of confidential care supported by education and by communication that confidential care for adolescents is normative and purposeful are effective strategies to introduce confidential care and develop family trust in confidential care (Lehrer et al., 2007; McKee et al., 2011). Standard scripts for providing confidentiality assurances are associated with an increased likelihood of providers spending time alone with the patient (Bravender et al., 2014; McKee et al., 2011; Riley et al., 2017). Providers should consider their 10 Volume ■■ • Number ■■ state’s confidentiality requirements when developing a script. A simple example as follows. Everything we discuss with you today is confidential with three exceptions: if you are at risk of immediate harm; if you are putting someone else at risk of immediate harm; if someone else is putting you in immediate harm (Wadman et al., 2014, p. e13). Scripts should include normative statements and purpose, such as “We do this for all teens … to encourage good communication” (McKee et al., 2011, p. 39). A split-visit model, where a portion of the visit is conducted with the provider and the patient and the remainder of the visit is conducted with parents present, facilitates confidential care. A greater number of topics were discussed in the split-visit model compared with visits with no confidential care or visits that were completely confidential (Gilbert et al., 2014). Motivational interviewing techniques are associated with assurances of confidentiality and may improve delivery of confidential care (Bravender et al., 2014). In addition to educating providers, parents, and patients about state confidentiality laws, the rationales for confidential care, and scripts to introduce time alone, documentation reminders, prompts, and role-play activities increase provider comfort with confidential care (Riley et al., 2017). Once time alone is established, multiple resources are available to guide assessing for risk behaviors (Table 2). The American Academy of Pediatrics’s (2016) Bright Futures Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care recommend initiation of alcohol and drug screening at 11 years of age. Extensive resources are available from the organization, including the CRAFFT (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble) screening tool for alcohol and other drugs (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2016). The American Medical Association’s Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services addresses health care delivery, anticipatory guidance, medical and risk behavior screening, and immunizations for patients aged 11 through 21 years (1997). Additional risk behavior screening tools include the HEEADSSS method of interviewing (Home environment, Education and employment, Eating, peerrelated Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicide/depression, and Safety from injury and violence) and the 21question Rapid Assessment for Adolescent Preventive Services screening tool (Klein, Goldenring, & Adelman, 2014; Salerno, Marshall, & Picken, 2012). A summary of strategies to develop a practice culture that supports confidential care is presented in Table 3. DISCUSSION The aim of this integrative review was to identify facilitators and barriers to confidential care and strategies to support implementing and providing confidential care. Many adolescents are not afforded time alone with Journal of Pediatric Health Care ARTICLE IN PRESS TABLE 2. Risk behavior screening tools and resources Tool/Resource Description American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures Comprehensive guidance for preventive care screenings Alcohol and Brief Intervention for Youth: Practitioners Guide CRAFFT screening tool Comprehensive resource Guideline for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS) HEADDSSS National Institute on Drug Abuse: Evidence-Based Screening Tools for Adults and Adolescents Rapid Assessment for Adolescent Preventive Services (RAAPS) tool Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine Screening Tools Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration 6 questions, high-risk alcohol/ drug use Comprehensive guide with screening tools (61-72 questions for adolescent, 15 questions for parent) Psychosocial history interview tool Resource materials and evidence-based screening tools https://brightfutures.aap.org/Pages/default.aspx https://brightfutures.aap.org/Bright%20Futures%20Documents/ Screening.pdf https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/YouthGuide/ YouthGuide.pdf http://www.ceasar-boston.org/CRAFFT/ Elster AB, Kuznets NJ, eds. AMA Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS): Recommendations and rationale. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. http://contemporarypediatrics.modernmedicine.com/contemporary -pediatrics/content/tags/adolescent-medicine/heeadsss-30 -psychosocial-interview-adolesce?page=0,0 https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/ tool-resources-your-practice/screening-assessment-drug-testing -resources/chart-evidence-based-screening-tools-adults 21-question screening tool for adolescent risk behaviors https://www.raaps.org/ Clinical care guidelines and screening tools for alcohol and drugs Resource guide and screening tools, including Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment https://www.adolescenthealth.org/Topics-in-Adolescent-Health/ Substance-Use/Clinical-Care-Guidelines/Screening-Tools.aspx providers. Based on findings from the U.S. studies, it seems likely that more than 40% of adolescents do not receive confidential care or receive it very infrequently (Edman, Adams, Park, & Irwin, 2010; Irwin et al., 2009). Older adolescents, females, or those with sexual complaints or the need for a private physical examination are more likely to receive confidential care than younger adolescents or males or those who do not present with symptoms suggesting the need for privacy (Denny et al., 2012; Gilbert et al., 2014; Klein et al., 1999; O’Sullivan et al., 2010). Trust emerged from the analysis as both necessary for effective confidential care and as difficult to establish, influenced by the relationships between adolescent and parent, parent and provider, and adolescent and provider. Provider assurances of confidentiality emerged as a strategy to increase adolescents’ trust of the provider, because such assurances are directly associated with an adolescent’s willingness to divulge sensitive information (Ford et al., 1997). Providers should be cognizant of the potential negative outcomes related to failure to provide confidential care. The evidence confirms the value of confidential care in providing an environment in which adolescents are more likely to discuss risk behaviors (Gilbert et al., 2014; Klein & Wilson, 2002). Practice Implications Nurse practitioners who provide care to adolescents should implement confidential care if they are not www.jpedhc.org Link https://www.samhsa.gov/sbirt/resources already providing it consistently. In the search for literature for this review, no studies were found that evaluated nurse practitioners’ provision of confidential care to adolescents. Simple techniques of chart reminders, interview scripts, education for staff and patients, and motivational interviewing strategies can be implemented to facilitate the practice of confidential care. Recognizing the risk associated with a lack of confidential care should encourage providers to allow adolescent patients opportunities for time alone during clinical encounters. Acknowledgement of, and respect for, the autonomy of adolescents can serve as the springboard for implementation of patient-centered communication strategies to simplify confidential care. Assurances of confidentiality and education for both patients and parents are integral to the process. When adolescents are not allowed opportunities for confidential discussion of sensitive topics or high-risk behaviors, we may be placing them at greater risk. Limitations Limitations of this review are in the relatively low level of evidence of most of the studies, which were primarily survey studies and qualitative focus groups. Although these methods are appropriate for identifying practice patterns, limitations of self-reporting affects the results, leaving questions to be answered regarding the true practice of confidential care. In addition, the focus was on physician care. These limitations set ■■ 2017 11 ARTICLE IN PRESS TABLE 3. Developing a practice culture that supports confidential care Strategy Focus Educate providers/staff Confidentiality laws Best practices Implications of confidential care Risk behavior screening tools Establish practice policies Confidential care Risk behavior screening guidelines Risk behavior screening tools Provide parent/ adolescent education Confidentiality laws Visit structure/expectations Implement a communication plan Scripts • Assurance of confidentiality • Introduction of confidential care • Purpose of confidential care normative statements Define visit structure for parents Incorporate motivational interviewing Process of confidential care (include front desk/support staff) Documentation Practice culture Consistency Split visit structure Standardized risk tools Establish workflow practices Methods Conduct baseline chart review/practice survey to determine current practice and knowledge/attitudes to inform education initiatives Develop and provide • Online education modules • In services • Handouts Develop and disseminate policies for • Providing confidential care • Screening for risk behaviors Review screening tools and decide which screening tools will be used in the practice Develop and use • Handouts for staff, parents, and patients • Practice welcome letter to parents • Posters in waiting rooms/examination rooms (state laws) Written script for various provider/support roles • Purpose: “to promote effective communication; to take better care of … ” • Normative: “We do this for all adolescents,” “It’s our routine” • Assurance of confidentiality Role play with scripts for various office staff Meet patients where they are Role play scenarios: introducing confidential care to parents/adolescents Routine evaluation of individuals and practice to ensure methods for establishing confidential care are being implemented consistently Medical record reminder flags and documentation templates Sources: Bravender et al. (2014); Gilbert et al. (2014); Lehrer et al. (2007); McKee et al. (2011); Riley, Ahmed, Lane, Reed, & Locke (2017); Rubin et al. (2010). the stage for future reWhen adolescents search to address the are not allowed gap in studies of nursing practice. There is a sigopportunities for nificant opportunity for confidential nurses to be a part of discussion of the solution for the confidential care problem, sensitive topics or through leading confihigh-risk dential care in advanced behaviors, we may practice or supporting confidential care as a be placing them at part of the extended greater risk. care team. Although some studies identified lack of time as a barrier to the provision of confidential care, none identified strategies for overcoming that barrier. Also largely missing was attention to the specific issue of confidential care for adolescents with chronic illnesses. The gap in research regarding practice of confidential care by nurse practitioners, strategies for managing issues related to lack of time, and issues of confidential care for adolescents with chronic illness suggest topics for future research. 12 Volume ■■ • Number ■■ CONCLUSION All adolescents should be allowed confidential care at every encounter with a health care professional. Strategies to implement confidential care exist and should be implemented in practice. Comprehensive practice change initiatives are likely required to significantly improve the rates of confidential care and facilitate effective risk behavior screening. REFERENCES American Academy of Pediatrics. (2016). Recommendations for preventive pediatric healthcare. Elk Grove Village, IL: Author. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/ periodicity_schedule.pdf American Medical Association. (1997). Guidelines for adolescent preventive services (GAPS): Recommendations monograph. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association. Borowsky, I. W., Ireland, M., & Resnick, M. D. (2009). Health status and behavioral outcomes for youth who anticipate a high likelihood of early death. Pediatrics, 124(1), e81-e88. Bravender, T., Lyna, P., Tulsky, J. A., Ostbye, T., Alexander, S. C., Dolor, R. J., Coffman, C.J., Lin, P.-H., Pollak, K. I. (2014). Physicians’ assurances of confidentiality and time spent alone with adolescents during primary care visits. Clinical Pediatrics, 53, 1094-1097. Braverman, P. K., Adelman, W. P., Alderman, E. M., Breuner, C. C., Levine, D. A., Marcell, A. V., O’Brien, R. (2017). The Journal of Pediatric Health Care ARTICLE IN PRESS adolescent’s right to confidential care when considering abortion. Pediatrics, 139(2), e20163861. Britto, M. T., Garrett, J. M., Dugliss, M. A. J., Johnson, C. A., Majure, J. M., & Leigh, M. W. (1999). Preventive services received by adolescents with cystic fibrosis and sickle cell disease. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 153, 27-32. Britto, M. T., Rosenthal, S. L., Taylor, J., & Passo, M. H. (2000). Improving rheumatologists screening for alcohol use and sexual activity. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 154, 478483. Britto, M. T., Tivorsak, T. L., & Slap, G. B. (2010). Adolescents’ needs for healthcare privacy. Pediatrics, 126(6), e1469-e1476. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 16-4984, NSDUH Series H-51). Rockville, MD: Substance abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/ NSDUH-FFR1-2015.pdf. Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services. (2014). Paving the road to good health strategies for increasing Medicaid adolescent wellcare visits. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.medicaid.gov/ medicaid/benefits/downloads/paving-the-road-to-good -health.pdf Connelly, L. M. (2009). Research roundtable: Systematic reviews. Medsurg Nursing, 18, 181-182. Dempsey, A. F., Singer, D. D., Clark, S. J., & Davis, M. M. (2009). Adolescent preventive health care: What do parents want? The Journal of Pediatrics, 155, 689-694. Denny, S., Farrant, B., Cosgriff, J., Hart, M., Cameron, T., Johnson, R., Mcnair, V., Utter, J., Crengle, S., Fleming T., Ameratunga, S., Sheridan, J., Robinson, E. (2012). Access to private and confidential health care among secondary school students in New Zealand. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51, 285291. Duncan, R. E., Jekel, M., O’Connell, M. A., Sanci, L. A., & Sawyer, S. M. (2014). Balancing parental involvement with adolescent friendly health care in teenagers with diabetes: Are we getting it right? Journal of Adolescent Health, 55, 59-64. Duncan, R. E., Vandeleur, M., Derks, A., & Sawyer, S. (2011). Confidentiality with adolescents in the medical setting: what do parents think? Journal of Adolescent Health, 49, 428-430. Edman, J. C., Adams, S. H., Park, M. J., & Irwin, C. E. (2010). Who gets confidential care? Disparities in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46, 393-395. Farrant, B., & Watson, P. D. (2004). Health care delivery: Perspectives of young people with chronic illness and their parents. Journal of Paediatric Child Health, 40, 175-179. Ford, C. A., Millstein, S. G., Halpern-Felsher, B. L., & Irwin, C. E. (1997). Influence of physician confidentiality assurances on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information and seek future health care: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, 1029-1034. Ford, C., English, A., & Sigman, G. (2004). Confidential health care for adolescents: Position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(2), 160-167. Gilbert, A. L., Rickert, V. I., & Aalsma, M. C. (2014). Clinical conversations about health: The impact of confidentiality in preventive adolescent care. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55, 672677. Hergenroeder, A. C., & Brewer, E. D. (2001). A survey of pediatric nephrologists on adolescent sexual health. Pediatric Nephrology, 16, 57-60. Hutchinson, J. W., & Stafford, E. M. (2005). Changing parental opinions about teen privacy through education. Pediatrics, 116, 966971. www.jpedhc.org Irwin, C. E., Adams, S. H., Park, M. J., & Newacheck, P. W. (2009). Preventive care for adolescents: Few get visits and fewer get services. Pediatrics, 123, e565-e572. Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Miech, R. A., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2016). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975-2016: 2016 Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. Klein, D. A., Goldenring, J. M., & Adelman, W. P. (2014). HEEADSSS 3.0: The psychosocial interview for adolescents updated for a new century fueled by media. Contemporary Pediatrics. Retrieved from http://contemporarypediatrics.modernmedicine.com/ contemporary-pediatrics/content/tags/adolescent-medicine/ heeadsss-30-psychosocial-interview-adolesce Klein, J. D., & Wilson, K. M. (2002). Delivering quality care: Adolescents’ discussion of health risks with their providers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 190-195. Klein, J. D., Wilson, K. M., McNulty, M., Kapphahn, C., & Collins, K. S. (1999). Access to medical care for adolescents: Results from the 1997 Commonwealth Fund Survey of the health of adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health Care, 25, 120130. Lehrer, J. A., Pantell, R., Tebb, K., & Shafer, M. A. (2007). Forgone health care among US adolescents: Associations between risk characteristics and confidentiality concern. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 218-226. Louis-Jacques, L., & Samples, C. (2011). Caring for teens with chronic illness: Risky business? Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 23, 367372. McKee, M. D., O’Sullivan, L. F., & Weber, C. M. (2006). Perspectives on confidential care for adolescent girls. Annals of Family Medicine, 4, 519-526. McKee, M. D., Rubin, S. E., Campos, G., & O’Sullivan, L. F. (2011). Challenges of providing confidential care to adolescents in urban primary care: Clinician perspectives. Annals of Family Medicine, 9, 37-43. Miauton, L., Narring, F., & Michaud, P. A. (2003). Chronic illness, life style and emotional health in adolescents: Results of a crosssectional survey on the health of 15-20 year olds in Switzerland. European Journal of Pediatrics, 162, 682-689. Nash, A. A., Britto, M. T., Lovell, D. J., Passo, M. H., & Rosenthal, S. L. (1998). Substance use among adolescents with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research, 11, 391396. National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Monitoring the future 2016 survey results. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved from https://www .drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/ monitoring-future-2016-survey-results Newhouse, R. P., Dearholt, S. L., Poe, S. S., Pugh, L. C., & White, K. M. (2007). Johns Hopkins Nursing evidence-based practice model and guidelines. Indianapolis: Sigma Theta Tau International. Nylander, C., Seidel, C., & Tindberg, Y. (2014). The triply troubled teenager—Chronic conditions associated with fewer protective factors and clustered risk behaviors. Acta Paediatrica, 103, 194-200. O’Sullivan, L., McKee, M. D., Rubin, S. E., & Campos, G. (2010). Primary care providers’ reports of time alone and the provision of sexual health services to adolescent patients: Results of a prospective card study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47, 110112. Purcell, J. S., Hergenroeder, A. C., Kozinetz, C., Smith, E. O., & Hill, R. B. (1997). Interviewing techniques with adolescents in primary care. Journal of Adolescent Health, 20, 300-305. Riley, M., Ahmed, S., Lane, J. C., Reed, B. D., & Locke, A. (2017). Using maintenance of certification as a tool to improve the ■■ 2017 13 ARTICLE IN PRESS delivery of confidential care for adolescent patients. Journal of Pediatric Adolescent Gynecology, 30, 76-81. Rubin, S. E., McKee, D., Campos, G., & O’Sullivan, L. F. (2010). Delivery of confidential care to adolescent males. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 23, 728-735. Salerno, J., Marshall, V. D., & Picken, E. B. (2012). Validity and reliability of the rapid assessment for adolescent preventive services adolescent health risk assessment. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50, 595-599. Sasse, R. A., Aroni, R. A., Sawyer, S. M., & Duncan, R. E. (2013). Confidential consultations with adolescents: An exploration of Australian parents’ perspectives. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 786-791. Searcy, L. (2017). The disease of addiction: A critical pediatric prevention issue. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 31, 2-4. Suris, J. C., Michaud, P. A., Akre, C., & Sawyer, S. M. (2008). Health risk behaviors in adolescents with chronic conditions. Pediatrics, 122, 1113-1118. 14 Volume ■■ • Number ■■ Suris, J. C., & Parera, N. (2005). Sex, drugs and chronic illness: Health behaviours among chronically ill youth. European Journal of Public Health, 15, 484-488. Tebb, K., Hernandez, L. K., Shafer, M. A., Chang, F., & Otero-Sabogal, R. (2012). Understanding the attitudes of Latino parents towards confidential health services for teens. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50, 572-577. van Hook, S., Harris, S. K., Brooks, T., Carey, P., Kossack, R., Kulig, J., Knight, J. R.; New England Partnership for Substance Abuse Research (NEPSAR) (2007). The “Six T’s”: Barriers to screening teens for substance abuse in primary care. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 456-461. Wadman, R., Thul, D., Elliott, A. S., Kennedy, A. P., Mitchell, I., & Pinzon, J. L. (2014). Adolescent confidentiality: Understanding and practices of health care providers. Paediatrics & Child Health, 19, e11-e14. Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrated review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 546-553. Journal of Pediatric Health Care