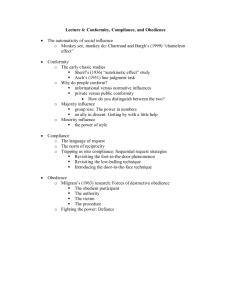

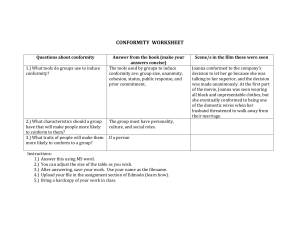

COMPLIANCE AND CONFORMITY In an individualistic society such as the United States, conformity has a negative connotation (Markus and Kitiyama 1994). Yet conformity is a fundamental social process without which people would be unable to organize into groups and take effective action as a collectivity. For people to coordinate their behavior so that they can organize and work together as a group, they must develop and adhere to standards of behavior that make each other’s actions mutually predictable. Simply driving down a street would be nearly impossible if most people did not conform to group norms that organize driving. ———, and Charles Lumsden 1990 ‘‘Theory and Research in Organizational Ecology.’’ Annual Review of Sociology 16:161–195. Small Business Administration 1994 Handbook of Small Business Data. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office and Office of Advocacy, Small Business Administration. Stinchcombe, Arthur 1965 ‘‘Social Structure and Organizations.’’ In J. G. March, ed., Handbook of Organizations. 142–193 Chicago: Rand-McNally. Swanson, Guy E. 1971 ‘‘An Organizational Analysis of Collectivities.’’ American Sociological Review 36:607–614. U.S. Bureau of the Census 1996 Selected statistics from the 1992 Census of Manufactures report MC92– S–2 ‘‘Concentration Ratios in Manufacturing.’’ http:/ /www.census.gov.mcd/mancen/download/ mc92cr.sum (21 Jan. 1999) Conformity is also the process that establishes boundaries between groups. Through the conformity process, the members of one group become similar to one another and different from those of another group. This, in turn, creates a shared social identity for people as the members of a distinctive group. Given the pressure of everchanging circumstances, social groups such as families, peer groups, business firms, and nations, only maintain their distinctive cultural beliefs and moderately stable social structures through the constant operation of conformity processes. Von Glinow, Mary Ann 1988 The New Professionals: Managing Today’s High-Tech Employees. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger. Williamson, Oliver 1981 ‘‘The Economics of Organization: The Transaction Cost Approach.’’ American Journal of Sociology 87:548–577. Zucker, Lynne G. (ed.) 1988 Institutional Patterns and Organizations: Culture and Environment. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger. Perhaps because it is essential for social organization, conformity appears to be a universal human phenomenon. The level of conformity varies by culture, however. Collectivist cultures (e.g., Japan) that emphasize the interdependence of individuals show higher levels of conformity than individualistic cultures (e.g., the United States) that focus on the independence of individuals (Bond and Smith 1996). HOWARD E. ALDRICH PETER V. MARSDEN COMPLIANCE AND CONFORMITY Conformity is a change in behavior or belief toward a group standard as a result of the group’s influence on an individual. As this definition indicates, conformity is a type of social influence through which group members come to share similar beliefs and standards of behavior. It includes the processes by which group members converge on a given standard of belief or behavior as well as the pressures they exert on one another to uphold such standards. Compliance is behavioral conformity in order to achieve rewards or avoid punishments (Kelman 1958). Since one can behaviorally adhere to a group standard without personally believing in it, the term is often used to indicate conformity that is merely public rather than private as well. Compliance can also refer to behavioral conformity to the request or demand of another, especially an authority. Although essential, conformity always entails a conflict between a group standard and an alternative belief or behavior (Asch 1951; Moscovici 1985). For their physical and psychological survival, people need and want to belong to social groups. Yet to do so, they must curb the diversity and independence of their beliefs and behavior. Without even being aware of it, people usually willingly adopt the group position. Occasionally, however, individuals believe an alternative to be superior to the group standard and suffer painful conflict when pressured to conform. Sometimes a nonconforming, deviate alternative is indeed superior to the group standard in that it offers a better response to the group circumstances. Innovation and change is as important to 400 COMPLIANCE AND CONFORMITY into a group standard. Thus, even when participants had well-established personal standards for judging, mere exposure to the differing judgments of others influenced them to gradually abandon their divergent points of view for a uniform group standard. This occurred despite a setting where the subjects, all strangers, had no power over one another and were only minimally organized as a group. a group’s ability to adjust and survive as is conformity. In fact, a nonconforming member can influence the majority opinion even as the majority pressures the deviate to conform. As Irving Janis (1972) points out in his analysis of ‘‘groupthink,’’ however, conformity pressures can grow so strong that they silence alternative opinions and strangle a group’s ability to critically analyze and respond to the problems it faces. Thus, conformity is a double-edged sword. It enables people to unify for collective endeavors but it exacts a cost in potential innovation. The Sherif experiment suggests that conformity pressures in groups are subtle and extremely powerful. But critics quickly noted that the extreme ambiguity of the autokinetic situation might be responsible for Sherif’s results. In such an ambiguous situation, participants have little to base their personal judgments on, so perhaps it is not surprising that they turn to others to help them decide what to think. Do people conform when the task is clear and unambiguous? Will they yield to a group consensus if it is obvious that the consensus is wrong? These are the questions Solomon Asch (1951, 1956) addressed in his classic experiments. CLASSIC EXPERIMENTS The social scientific investigation of conformity began with the pioneering experiments of Muzafer Sherif (1936). They beautifully illustrate the easy, almost unconscious way people in groups influence one another to become similar. Sherif made use of the autokinetic effect, which is a visual illusion that makes a stationary pinpoint of light in a dark room appear to move. Sherif asked subjects in his experiments to estimate how far the light moved. To eliminate ambiguity, Asch employed clearcut judgment tasks where subjects chose which of three comparison lines was the same length as a standard line. The correct answers were so obvious that individuals working alone reached 98 percent accuracy. Similar to the Sherif experiment, Asch’s subjects gave their judgments in the presence of seven to nine of their peers (all participants were male college students). Unknown to the single naive subject in each group, all other group members were confederates of the experimenter. On seven of twelve trials, as the confederates announced their judgments one by one, they unanimously gave the wrong answer. It was arranged so that the naive subject always gave his judgment after the confederates. When individuals estimated the light alone, their estimates were often quite divergent. In one condition of the experiment, however, subjects viewed the light with two or three others, giving their estimates out loud, allowing them to hear each other’s judgments. In this group setting, individuals gave initial estimates that were similar to one another and rapidly converged on a single group estimate. Different groups settled on very different estimates but all groups developed a consensus judgment that remained stable over time. After three sessions together, group members were split up. When tested alone they continued to use their group standard to guide their personal estimates. This indicates that the group members had not merely induced one another to conform in outward behavior. They had influenced one another’s very perception of the light so that they believed the group estimate to be the most accurate judgment of reality. The subject here was placed in a position of absolute conflict. Should he abide by what he knows to be true or go along with the unanimous opinion of others? A third of the time subjects violated the evidence of their own senses to agree with the group. In another condition, Sherif first tested subjects alone so that they developed personal standards for their estimates. He then put together two or three people with widely divergent personal standards and tested them in a group setting. Over three group sessions, individual estimates merged The Asch experiments clearly demonstrated that people feel pressure to conform to group standards even when they know the standards are wrong. It is striking that Asch, like Sherif, obtained these results with a minimal group situation. The 401 COMPLIANCE AND CONFORMITY rewards or avoid unpleasant costs. Thus it is normative influence that is behind compliance. People depend on others for many valued outcomes, such as inclusion in social relationships, a sense of shared identity, and social approval. Because of this dependency, even strangers have some power to reward and punish one another. Asch’s results are a good example. Although a few of Asch’s participants actually doubted their judgment (informational influence), most conformed in order to avoid the implicit rejection of being the odd person out. Studies show that fears of rejection for nonconformity are not unfounded (see Levine 1980 for a review). While nonconformists are sometimes admired, they are rarely liked. Furthermore, they are subject to intense persuasive pressure and criticism from the majority. group members were strangers who meant little to one another. Yet they exerted substantial influence over one another simply by being in the same situation together. Because of the dramatic way it highlights the conflict inherent in conformity between individuals and groups, Asch’s experimental design has become the paradigm for studying conformity. NORMATIVE AND INFORMATION INFLUENCE Sherif’s and Asch’s striking results stimulated an explosion of research to explain how conformity occurs (see Kiesler and Kiesler 1976, Cialdini and Trost 1998 for reviews). It is now clear that two analytically distinct influence processes are involved. Either or both can produce conformity in a given situation. Morton Deutsch and Harold Gerard (1955) labelled these informational influence and normative influence. FACTORS THAT INCREASE CONFORMITY Anything that increases vulnerability to informational and normative influence increases conformity. Although there may be personality traits that incline people to conform, the evidence for this is conflicting (Crowne and Marlowe 1969; Moscovici 1985). Situational factors seem to be the most important determinants of conformity. Research indicates that conformity is increased by a) the ambiguity or difficulty of the task, b) the relative unimportance of the issue to the person, c) the necessity of making a public rather than private response, d) the similarity of group members, e) high interdependence among the group members, f) the attractiveness and cohesiveness of the group, and g) the unanimity of the majority (see Kiesler and Kiesler 1976; Cialdini and Trost 1998 for reviews). In informational influence, the group defines perceptual reality for the individual. Sherif’s experiment is a good illustration of this. The best explanation derives from Leon Festinger’s (1954) social comparison theory. According to the theory, people form judgments about ambiguous events by comparing their perceptions with those of similar others and constructing shared, socially validated definitions of the ‘‘reality’’ of the event. These consensual definitions constitute the social reality of the situation (Festinger 1950). Because people want the support of others to assure them of the validity of their beliefs, disagreeing with the majority is uncomfortable. People in such situations doubt their own judgment. They change to agree with the majority because they assume that the majority view is more likely to be accurate. When a task or situation is ambiguous or difficult, it is not easy to tell what the best response to it would be. As a result, much as in Sherif’s experiments, group members rely heavily on each other’s opinions to decide what is best, increasing their susceptibility to informational influence. When decision-making groups in government or business face complex, difficult decisions where the right choice is uncertain, informational influence increases the members’ tendency to agree and can affect their critical analysis of the situation (Janis 1972). Tastes and beliefs about matters, such as clothing style or music, about which there are no objectively right choices are subject to As this indicates, conformity as a result of informational influence is not unwilling compliance with the demands of others. Rather, the individual adopts the group standard as a matter of private belief as well as public behavior. Informational influence is especially powerful in regard to social beliefs, opinions, and situations since these are inherently ambiguous and socially constructed. Normative influence occurs when people go along with the group majority in order to gain 402 COMPLIANCE AND CONFORMITY task, the naive subjects’ conformity to the majority dropped from a third to only 5 percent. One fellow dissenter shows an individual that nonconformity is possible and provides much needed social support for an alternate construction of social reality. Interestingly, a dissenter need not agree with an individual to encourage nonconformity. It is only necessary that the dissenter also break with the majority. sudden fads or fashions for similar reasons. Powerful conformity processes take over as group standards define for the individual what the ‘‘right’’ clothes or music are. The less people care about an issue, the more open they are to both informational and normative influence. Without the motivation to examine an issue personally, people usually accept the group standard about it, both because the agreement of others makes the standard seem right and because there are more rewards and fewer costs in going along with the group. Because of such rewards and costs, people are especially likely to go along when their response must be public rather than private. Another factor that affects conformity is the sex composition of the group. Although the results of studies are inconsistent, statistical summaries of them, called meta-analyses, indicate that there is an overall tendency for women to conform slightly more than men (Becker 1986; Eagly and Wood 1985). Sex differences in conformity are most likely when behavior is under the surveillance of others. The evidence suggests two explanations (see Eagly 1987 for a review). First, sex carries status value in interaction, which creates social expectations for women to be less competent and influential in the situation than men (Ridgeway 1993). Second, sex stereotypes pressure men to display independence when they are being observed. Since people compare their perceptions and views most closely to those of people who are socially similar to them, similarity increases group members’ informational influence on one another. Similarity also increases liking and, when people like one another, they have more power to reward or punish each other, so normative influence increases as well. Because of the increased power of both informational and normative influence, conformity pressures are often especially strong in peer groups. When members are highly dependent on one another for something they value, conformity pressure increases because the members have more power to reward or frustrate one another (normative influence). Similarly, when a group is very attractive to an individual, its members have more power to normatively influence the individual. Gangs, fraternities, and professional societies all use this principle to induce new members to adopt their groups’ distinctive standards. Also, when a group is very tight knit and cohesive, members’ commitment to the group gives it more power over their behavior, increasing the forces of conformity. THE INFLUENCE OF THE MINORITY ON THE MAJORITY Conformity arises out of a social influence process between an individual and the group majority. The influence process is not always one way, however. As Serge Moscovici (1976) points out, a dissenting group member is not just a recipient of pressure from the majority, but also someone who, by breaking consensus, challenges the validity of the majority view, creating conflict, doubt, and the possibility of opinion change in the group. Dissenters sometimes modify the opinion of the majority in a process called minority influence. Research shows that for a minority opinion to affect the majority it must be presented consistently and clearly without wavering and it helps if there are two such dissenters in the group rather than one (see Moscovici 1985; Moscovici, Mucchi-Faina, and Maass 1994; Wood et al. 1994, for reviews). A dissenting minority increases divergent thinking among group members that can enhance the likelihood that they will arrive at creative solutions to the problems the group faces (Nemeth 1986). The unanimity of the majority in a group is an especially important factor in the conformity process. In his studies, Asch (1951) found that as long as it was unanimous, a majority of three was as effective in inducing conformity as one of sixteen. Subsequent research generally confirms that the size of a majority past three is not a crucial factor in conformity. It is unanimity that counts (see Allen 1975 for a review). When Asch (1951) had one confederate give the correct answer to the line 403 COMPLIANCE AND CONFORMITY electric shocks to another person. The shock generator used by the subject labelled increasing levels as ‘‘danger-severe shock’’ and ‘‘XXX’’ (at 450 volts). The victim (a confederate who received no actual shocks) protested, cried out, and complained of heart trouble. Despite this, 65 percent of the subjects complied with the scientist-experimenter and shocked the victim all the way to the 450 volt maximum. It is clear that most of the time, people do as they are told by legitimate authorities. CONFORMITY AND STATUS Research in the Asch and Sherif paradigms focuses on conformity pressures among peers. However, when group members differ in status, it affects the group’s tolerance of their nonconformity. Higher status members receive fewer sanctions for nonconformity than lower status members (Gerson 1975). As long as they adhere to central group norms, high status members’ nonconformity can actually increase their influence in the group (Berkowitz and Macauley 1961). Edwin Hollander (1958) argues that, because high status members are valued by the group, they are accorded ‘‘idiosyncrasy credits’’ that allow them to nonconform and innovate without penalty as long as they stay within certain bounds. It is middle status members who actually conform the most (Harvey and Consalvi 1960). They have fewer idiosyncrasy credits than high status members and more investment in the group than low status members. Uncertainty over their responsibilities in the situation (a definition of social reality issue) and concern for the authority’s ability to punish or reward them seem to be the principle causes for people’s compliance in such circumstances. Note the comparability of these factors to informational and normative influence. Situational factors that socially define the responsibility question as a duty to obey rather than to disobey increase compliance (Kelman and Hamilton 1989), as do factors that increase the authority’s ability to sanction. Nonconformity can also affect the position of status and influence a person achieves in the group. Hollander (1958, 1960) proposed that individuals earn status and idiosyncrasy credits by initially conforming to group norms, but replications of his study do not support this conclusion (see Ridgeway 1981 for a review). Conformity tends to make a person ‘‘invisible’’ in a group and so does little to gain status. Nonconformity attracts attention and gives the appearance of confidence and competence which can enhance status. But it also appears self-interested, which detracts from status (Ridgeway 1981). Consequently, moderate levels of nonconformity are most likely to facilitate status attainment. Research has demonstrated several such factors. Compliance is increased by the legitimacy of the authority figure and his or her surveillance of the individual’s behavior (Milgram 1974; Zelditch and Walker 1984). When others in the situation obey or when the individual’s position in the chain of command removes direct contact with the victim, compliance increases (Milgram 1974). On the other hand, when others present resist the authority, compliance drops dramatically. Stanley Milgram (1974) found that when two confederates working with the subject refused to obey the experimenter, only 10 percent of subjects complied fully themselves. As with a fellow dissenter from a unanimous majority, other resisters define disobedience as appropriate and provide support for resisting. In an analysis of ‘‘crimes of obedience’’ in many government and military settings, Herbert Kelman and Lee Hamilton (1989) show how such factors lead to compliance to illegal or immoral commands from authority. COMPLIANCE WITH AUTHORITY Reacting to the Nazi phenomenon of World War II, studies of compliance to authority have focused on explaining people’s obedience even when ordered to engage in extreme or immoral behavior. Compliance in this situation is comparable to conformity in the Asch paradigm in that individuals must go against their own standards of conduct to obey. The power of a legitimate authority to compel obedience was dramatically demonstrated in the Milgram (1963, 1974) experiments. As part of an apparent learning study, a scientist-experimenter ordered subjects to give increasingly strong Conformity and compliance are fundamental to the development of norms, social organization, group culture, and people’s shared social identities. As a result, research on conformity and compliance continues to develop in several directions. Efforts are underway to develop broader models of the social influence process that can incorporate both conformity and compliance (see Cialdini 404 COMPLIANCE AND CONFORMITY Gerson, Lowell W. 1975 ‘‘Punishment and Position: The Sanctioning of Deviants in Small Groups.’’ In P. V. Crosbie, ed., Interaction in Small Groups. New York: Macmillan. and Trost 1998). These efforts give added emphasis to people’s dependence on social relationships and groups and address questions such as whether minority and majority influence work through different or similar processes. Also, new, more systematic cross-cultural research attempts to understand both what is universal and what is culturally variable about conformity and compliance (Markus and Kitiyama 1994; Smith and Bond 1996). Harvey, O. J., and Conrad Consalvi 1960 ‘‘Status and Conformity to Pressures in Informal Groups.’’ Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 60:182–187. Hollander, Edwin P. 1958 ‘‘Conformity, Status, and Idiosyncrasy Credit.’’ Psychological Review 65:117–127. ——— 1960 ‘‘Competence and Conformity in the Acceptance of Influence.’’ Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 61:365–369. REFERENCES Allen, Vernon L. 1975 ‘‘Social Support for Nonconformity.’’ In L. Berkowitz, ed., Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 8, 2–43. New York: Academic Press. Janis, Irving L. 1972 Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin. Asch, Solomon E. 1951 ‘‘Effects of Group Pressure Upon the Modification and Distortion of Judgments.’’ In H. Guetzkow, ed., Groups, Leadership, and Men. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Press. Kelman, Herbert C. 1958 ‘‘Compliance, Identification, and Internalization: Three Processes of Attitude Change.’’ Journal of Conflict Resolution 2:51–60. ———, and V. Lee Hamilton 1989 Crimes of Obedience. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ——— 1956 ‘‘Studies of Independence and Submission to Group Pressure: I. A Minority of One Against a Unanimous Majority.’’ Psychological Monographs 70 (9, whole no. 416). Kiesler, Charles A. and Sara B. Kiesler 1976 Conformity. 2d ed. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. Levine, John M. 1980 ‘‘Reaction to Opinion Deviance in Small Groups.’’ In P. Paulus, ed., Psychology of Group Influence. Hillsdale, N.J.: Earlbaum. Becker, B. J. 1986 ‘‘Influence Again: Another Look at Studies of Gender Differences in Social Influence.’’ In Janet Shibley Hyde and Marci C. Lynn, eds., The Psychology of Gender: Advances Through Meta-Analysis. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Markus, Hazel R., and S. Kitiyama 1994 ‘‘A Collective Fear of the Collective: Implications for Selves and Theories of Selves.’’ Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20:568–579. Berkowitz, Leonard, and J. R. Macaulay 1961 ‘‘Some Effects of Differences in Status Level and Status Stability.’’ Human Relations 14:135–147. Milgram, Stanley 1963 ‘‘Behavioral Study of Obedience.’’ Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67:371–378. Bond, M. H. and P. B. Smith 1996 ‘‘Culture and Conformity: A Meta-Analysis of Studies Using Asch’s Line Judgment Task.’’ Psychological Bulletin119:111–137. ——— 1974 Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. New York: Harper and Row. Cialdini, Robert B., and Melanie R. Trost 1998 ‘‘Social Influence: Social Norms, Conformity, and Compliance.’’ In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey, eds., The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed., vol. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill. Moscovici, Serge 1976 Social Influence and Social Change. London: Academic Press. ——— 1985 ‘‘Social Influence and Conformity.’’ In G. Lindzey and E. Aronson, eds., The Handbook of Social Psychology. 3d ed., vol. 2. New York: Random House. Crowne, D. P., and D. Marlowe 1964 The Approval Motive: Studies in Evaluative Dependence. New York: Wiley. ———, A. Mucchi-Faina, and A. Maass 1994 Minority Influence. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. Eagly, Alice H. 1987 Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation. Hillsdale, N.J.: Earlbaum. Nemeth, Charlan 1986 ‘‘Differential Contributions of Majority and Minority Influence.’’ Psychological Review 93:23–32. ———, and Wendy Wood 1985 ‘‘Gender and Influenceability: Stereotype vs. Behavior.’’ In V. E. O’Leary, R. K. Unger, and B. S. Walson, eds., Women, Gender and Social Psychology. Hillsdale, N.J.: Earlbaum. Ridgeway, Cecilia L. 1981 ‘‘Nonconformity, Competence, and Influence in Groups: A Test of Two Theories.’’ American Sociological Review 46:333–347. Festinger, Leon 1950 ‘‘Informal Social Communication.’’ Psychological Review 57:217–282. ——— 1993 ‘‘Gender, Status, and the Social Psychology of Expectations.’’ In P. England, ed., Theory on Gender/Feminism on Theory. New York: Aldine. ——— 1954 ‘‘A Theory of Social Comparison Processes.’’ Human Relations 7:117–140. 405 COMPUTER APPLICATIONS IN SOCIOLOGY Sherif, Muzafer 1936 The Psychology of Social Norms. New York: Harper and Row. Only a decade later many social scientists were exploring ways to use computers in their research. In the early 1960s, the first book devoted entirely to computer applications in social science research (Borko 1962) was published. Not only were social scientists writing about how to apply computers, they were designing and developing new software. Some of the most popular statistical software packages, e.g., SPSS (Nie, Bent, and Hull 1975), were developed by social scientists. Wood, Wendy, S. Lundgren, J. A. Ouelette, S. Busceme, and T. Blackstone 1994 ‘‘Minority Influence: A MetaAnalytic Review of Social Influence Processes.’’ Psychological Bulletin 115:323–345. Zelditch, Morris, Jr., and Henry A. Walker 1984 ‘‘Legitimacy and the Stability of Authority.’’ In E. Lawler, ed., Advances in Group Processes, vol. 1. Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press. During the 1980s, universities and colleges began to acquire microcomputers, accepting the premise that all researchers needed their own desktop computing equipment. The American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) survey in 1985 (Morton and Price 1986) reported that 50 percent of sociologists had a computer for exclusive use. A survey of academic departments supported by the American Sociological Association (Koppel, Dowdall, and Shostak 1985) found that slightly less than half of the sociology faculty reported to have immediate access to microcomputers. To put these findings into a more complete perspective, of the approximately 9,000 sociologists in 1985, about 4,500 had their own computers and about 5,200 reported routine computer use. Now, it is hard to find a sociologist’s office without at least one computer. And in many countries most students in sociology have a computer for writing papers and accessing online resources. CECILIA L. RIDGEWAY COMPLEMENTARITY See Mate Selection Theories. COMPUTER APPLICATIONS IN SOCIOLOGY Most sociologists, both professionals and students, now have their own computer with direct access to a printer for writing and to the Internet for electronic mail (e-mail). Beyond the basic tasks of writing and e-mailing are a variety of other computer-supported research applications, both quantitative and qualitative. This article describes how sociologists and other social scientists use these applications and what resources are available. Sociology and the Web. The Internet may be one of the largest and probably the most rapidly growing peaceful social movements in history. It is not just a technology, or a family of technologies, but a rapidly evolving socio-cultural phenomena often called ‘‘cyberspace’’ or ‘‘cyberculture.’’ No matter how this phenomena is defined, it is changing the way sociologists conduct their work. The data and modeling requirements of social research have united sociologists with computers for over a hundred years. It was the 1890 U. S. census that inspired Herman Hollerith, a census researcher, to construct the first automated data processing machinery. Hollerith’s punchcard system, while not a true computer by today’s definitions, provided the foundation for contemporary computer-based data management. By the mid-1990s sociology, like most other academic disciplines, had come to depend upon email. In addition, a rapidly growing number had begun to use the World Wide Web (WWW), commonly called the Web (Babbie 1996). Bainbridge (1995) claimed that the Web is ‘‘a significant medium of communication for sociologists, and extrapolation of present trends suggests it may swiftly become the essential fabric of sociology’s existence.’’ In January 1999, the author searched Web sites with the Alta Vista search engine for the word In 1948 the U. S. Bureau of the Census, anticipating the voluminous tabulating requirements of the 1950 census, contracted for the building of Univac I, the first commercially produced electronic computer. The need to count, sort, and analyze the 1950 census data on this milestone computer led to the development of the first highspeed magnetic tape storage system, the first sortmerge software package, and the first statistical package, a set of matrix algebra programs. 406