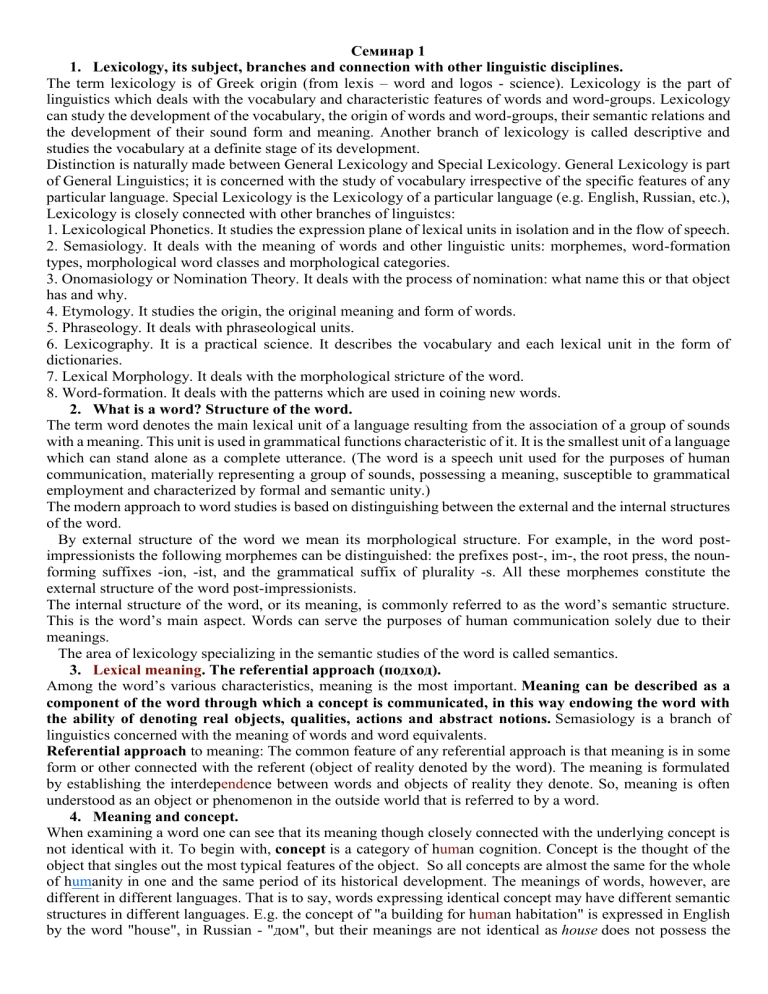

Lexicology Seminar Notes: Meaning, Morphemes, and Word Structure

advertisement