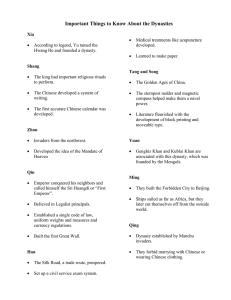

Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia Imperialism and the beginnings of modernisation China's leaders were forced to examine ways of trying to turn the tide of humiliation and defeat inflicted by comparatively small numbers of troops fighting a long way from home. One major faction advocated trying to defeat the West through its own strengths - namely, superior technology derived from industrialisation. In 1861, a very large power struggle at court brought greater influence to this 'modernisation' group of officials. In the 1860s, moves were taken to learn from the West by introducing modern munitions and machinery. China purchased seven steamships from Britain in 1862. In the middle of the same year, a central CoHege of Foreign Languages began taking students who would be able to speak, read and write the languages of the imperialist powers. In 1866, the College of Foreign Languages opened a scientific department of astronomy and mathematics. The tentative beginnings of modernisation were anything but smooth sailing. Many in the bureaucracy, induding officials at very senior levels, continued to oppose anything to do with this Western-style modernity. Their view was that Confucianism had served China very well for a very long time and that China's decline was due to moral failure, not to inferior technology. A further debate about the advantages of Western knowledge was touched off in 1867 by the following memorial from Woren, a very senior Mongol official and tutor to the Emperor. Document 1.5 A conservative reaction to Western knowledge Your slave has learned that the way to establish a nation is to lay emphasis on propriety and righteousness, not on power and plotting. The fundamental effort lies in the minds of people, not in techniques. Now, if we seek trifling arts and respect barbarians as teachers regardless of the possibility that the cunning barbarians may not teach us their essential techniques even if the teachers sincerely teach and the students faithfully study them, all that can be accomplished is the training of mathematicians. From ancient down to modern times, your slave has never heard of anyone who could use mathematics to raise the nation from a state of decline or to strengthen it in time of weakness. The empire is so great that one shou Id not worry lest there be any lack of abilities therein. If astronomy and mathematics have to be taught, an extensive search should find someone who has mastered the technique. Why is it limited to barbarians, and why is it necessary to learn from the barbarians? 10 China I: The Late Qing Dynasty Moreover, the barbarians are our enemies. In 1860 they took up arms and rebelled against us. Our capital and its suburbs were invaded, our ancestral altar was shaken, our Imperial palace was burned, and our officials and people were killed or wounded. There had never been such insults during the last 2000 years of our dynasty. All our scholars and officials have been stirred with heart-burning rage, and have retained their hatred until the present. Our court could not help making peace with the barbarians. How can we forget this enmity and this humiliation even for one single day? Source: As quoted in Ssu-yu Teng et al., China's Response to the West, A Documentary Survey, 1839-1923, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1954, p. 76 Questions 1 Sum up Woren's arguments against learning from the barbarians. 2 List the reasons Woren provides to justify his view that the barbarians are China's enemies. 3 Why do you think that Woren refers to himself as 'your slave' in this memorial? 4 Form a small group in class and prepare a response to Woren's memorial. Allocate one of the following roles to each person in the group: • the Emperor in 1867 • a senior official from the southern part of China, opposed to Woren's views • a visiting Western professor who teaches at the College of Foreign Languages • a respected Confucian scholar based at the Celestial Court • a reformist official keen to see China industrialise as soon as possible • a 'modernist' official, opposed to Woren and concerned that his views are retarding China. When you have finished preparing your response, imagine that you are presenting it at the Celestial Court. ~\.- Woren's view had a great deal of support. The Empress Dowager succeeded in seizing power at court in the 1870s. She was the aunt of the young Guangxu Emperor, who ascended the throne in 1875. Initially she followed a very conservative approach to modernisation. Early attempts to build that most characteristic of Western colonial structures - railways - were stoutly resisted by the conservative Chinese. In the middle of 1876, a short railway leading from Shanghai was opened, but within a few weeks a man was crushed to death in an accident. As a result, demands for the railway to be closed were successful and the tracks were torn up the next year. From an economic point of view, however, the benefits of modernisation proved impossible to deny. Railways were inevitably at the forefront of this modernisation. Despite the catastrophe of 1876, foreign powers - 11 Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia proceeded with the building of other railways. They built a series of railways through much of China, and most of the main ones are in place to this day. The following picture, from a Shanghai magazine of 1884, shows a Chinese impression of a foreign steam train. Document 1.6 A Chinese view of Western modernisation Source: John Gittings, A Chinese View of China, Pantheon Books, New York, 1973, pp. 76-7 Questions 12 In what ways has the artist depicted some of the different responses from the Chinese towards the introduction of railways in this illustration 7 Suggest at least three different examples. 2 Do you think the artist was in favour of the introduction of this railway line or opposed to it? How did you come to your decision? 3 How reliable might this impression, reprinted from a Shanghai magazine of 1884, be as an item of evidence about Chinese reactions towards the foreign railway? Do you think that visual impressions are as useful as written records when it comes to investigating attitudes towards the impact of Western technology in China? Discuss your ideas with another student. China I: The Late Qing Dynasty 7 The later decades of the nineteenth century saw the introduction of a range of things in China that we still associate with the 'modern' world today. There were many other examples of modernisation apart from the railways. Amongst the more obvious examples was the Jiangnan Arsenal, set up in Shanghai in 1865 and completing its first steamship in 1868. The Fuzhou Dockyard in Fuzhou in China's south-east began formal operations in January 1868 and, in 1878, work began at the Kaiping Coal Mines in Tianjin. Modernisation also affected culture. One of the most important moves was to send students to the West to study what had made the Western nations so powerful. The Chinese authorities hoped that these things could be introduced into China. In 1872, the first group of thirty Chinese students left Shanghai bound for the USA. Five years later, the first group of students and apprentices bound for Europe set sail for England and France, where they studied manufacturing and transportation. The authorities may have wanted the technological advantages of Western industrialisation and imperialism, but they were adamantly opposed to the suggestion that China should adopt Western political institutions or ideas. Under the unequal treaties, China had been forced to allow Christian missionaries to work in China - at first only in the main coastal areas, but later, inland as well. These missionaries were the cause of serious problems concerning cross-cultural tolerance. Their converts received favourable treatment, sometimes in the form of a better standard ofliving. This gave rise to the term 'rice Christians'. Many were able to have legal cases handled according to foreign law, which treated them much more leniently than did Chinese law. In the 1860s, a series of anti-Christian riots took place in widely scattered parts of China. The climax of these was the 'Tianjin massacre'. In this unhappy incident, popular anger against a French Catholic orphanage led to a mass siege of the church on the afternoon of 21 June 1870. The people believed--the orphanage was kidnapping Chinese children to convert them to Catholicism. The French consul shot at, but missed, two very senior Chinese officials, and was himself killed by the crowd. The people then went on to mutilate and kill every French person they could find and plunder and set fire to the French consulate, the orphanage and the church. By nightfall, over thirty Chinese converts and over twenty foreigners, including seventeen French people, had been killed. One of the major issues raised by imperialism in China, including the arrival of missionaries, was that of extraterritoriality. Foreigners in China believed it was their right to have any legal cases adjudicated according to the laws of their own country, not those of China. It was normal for colonists to bring with them the laws of their mother country. The Qing government agreed to allow extraterritoriality in China by signing a series of agreements with various powers, including Sweden, Norway, Britain, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, Prussia, Italy and 13 Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia Mexico. The following description of how extraterritoriality worked was written by a Chinese in 1912. Document 1. 7 Extraterritoriality With regard to controversies in China in which Chinese subjects are not involved, the principle which China observes is that of non-intervention. Questions of rights, whether personal or of property, arising in China between subjects of the same treaty power are subject to the jurisdiction and regulated by the authorities of their own government. Those occurring in Chinese territory between the subjects of two different powers are disposed of in accordance with the provisions of treaties existing between them. In such cases the general practice is that they are arranged officially by the consuls of both parties without resort to litigation; but where amicable settlement is impossible, the principle of jurisdiction followed is the same as in those between China and a foreign power, namely, that the plaintiff follows the defendant into the court of the latter's nation. Source: V. K. Wellington Koo, The Status of Aliens in China, p. 179, as quoted in En-sai Tai, Treaty Ports in China (A Study in Diplomacy), University Publications of America, Arlington, Virginia, 1976, p. 16S Questions 2 3 4 5 6 14 According to this source, what does non-intervention mean in terms of foreigners in China? Do you think that in cases where amicable settlement is impossible, a foreigner would ever be subject to China's laws? Refer to the document to justify your point of view. What do you think the attitude of this Chinese source is towards extraterritoriality? How did you arrive at your opinion? How reliable might this document be as an item of evidence about the extent of extraterritoriality in China during the Qing government? Identify some modern examples of extraterritoriality or a similar situation. Comment on their significance and compare them to the situation in China in the nineteenth century. Now consider some modern situations where foreigners are subject to the laws and judicial system of the country in which they are working or travelling. What sorts of controversial issues arise when foreigners break the law? Discuss with another student some of those cases that have been reported in the media. What advice would you give someone travelling or working in another country in terms of the legal and judicial system? China I: The Late Qing Dynasty The last decade of the nineteenth century r The imperialist onslaughts against China gathered momentum as the nineteenth century neared its end. Japan underwent successful modernisation following the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Not long afterwards it began to show signs of becoming an imperialist country itself in China and elsewhere (see chapter 7). Competition for influence in China's main tributary state, Korea (see chapter 6), was the primary reason for the outbreak of the first Sino-Japanese War in August 1894. In the following edict, the Guangxu Emperor explains why China was fighting against Japan. Document 1.8 Imperial edict on the war against Japan It was found a difficult matter to reason with the Wojen [literally 'dwarfs', a term of contempt for the Japanese]. Although we have been in the habit of assisting our tributaries [in this case referring to Korea], we have never interfered with their internal government. Japan's treaty with Korea was as one country with another; there is no law for sending large armies to bully a country in this way, and compel it to change its system of government. The various powers are united in condemning the conduct of the Japanese, and we can give no reasonable name to the army she now has in Korea. Nor has Japan been amenable to reason, nor would she listen to the exhortation to withdraw her troops and confer amicably upon what should be done in Korea ... As Japan has violated the treaties and not observed international laws, and is now running rampant with her false and treacherous actions commencing hostilites herself, and laying herself open to condemnation by . the various powers at large, we therefore desire to make it known to the' world that we have always followed the paths of philanthropy and perfect justice throughout the whole complications, while the Wojen, on the other hand, have broken all the laws of nations and treaties which it passes our patience to bear with. Hence we commanded Li Hung-chang [Hongzhang] to give strict orders to our various armies to hasten with all speed to root the Wojen out of their lairs. Source: As quoted in Harley Farnsworth MacNair, Modern Chinese History, Selected Readings, Commercial Press, Shanghai, 1923, pp. 532-4 Questions According to the Emperor, what was China's relationship with Korea like before the Japanese sent in their army? 2 List the accusations against Japan made by the Emperor in this edict. 3 Do you think these accusations justify the Emperor's orders to 'root the Wojen 15 Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia out of their lairs'? Justify your view and make reference to the document in your response. 4 Consider the language used by the Emperor in the last sentence of this document. What does it suggest about his attitude towards the Japanese 7 Do you think that the Emperor's attitude might be representative of the Chinese people at this time? Explain your point of view. 5 Prepare your response to this question with another student. Imagine that you are Li Hongzhang and you are about to announce that China is at war with Japan, as the Emperor has commanded. Prepare your speech to the key generals of the various Chinese armies at your disposal. In this speech you need to explain why war is being declared against the Japanese, to stress the need to defend the Emperor's honour and to arouse Chinese nationalism. China was disastrously defeated by the Japanese and forced to sign the humiliating Treaty ofShimonoseki in April 1895. Under this treaty, China had to pay an enormous indemnity to Japan, meaning that it was required to pay for the expenses incurred by Japan in inflicting the defeat. It was forced to cede certain territories to Japan, including Taiwan, which became a colony of Japan until its own defeat in 1945. The Treaty of Shimonoseki struck the last nail into the coffin of the Chinese traditional tribute system by acknowledging that Chinese influence in Korea had totally lost out to Japanese. The end of the nineteenth century saw yet further imperialist attacks on China, with a whole series of countries competing for concessions. The best known of the arrangements agreed upon in 1898, the year of 'the scramble for concessions', was a Sino-British convention signed on 9 June. Under this agreement, the British took out a ninety-nine-year lease on parts of Kowloon, the mainland area just opposite the island of Hong Kong. In the same year, some reformers led by Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao succeeded in persuading the Guangxu Emperor to introduce some very radical and far-reaching changes to China's administration, all in line with Western notions of modernity. However, the Empress Dowager had other ideas. She had the Emperor put under house arrest and several of the leading reformers were either arrested or executed. Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao both left China. 16 Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia The Boxer uprising and imperialist invasion of China The reaction of the Chinese masses to imperialism and the missionaries it fostered and protected reached a climax in 1900. The movement was called the Boxer uprising and was spearheaded by the 'Boxers'. The formal name of the Boxer organisation was the Militia of Harmonious Fists because of its members' belief in a kind of magic boxing. The Boxers began in Shandong province, to the south of Beijing. They directed their anger mainly against the Germans, to whom major concessions had been made in Shandong through a convention signed in March 1898. The Boxers then marched north, storming into the capital Beijing in large numbers in June 1900, and proceeded to besiege the legations of the imperialist powers. The following is a translation of a Boxer poster stuck on the walls of Beijing. Document 1.10 A Boxer poster Our Emperor is about to become powerful. The leader of the 'Boxers' is a royal person. Within three months all foreigners will be killed and driven away from China. During forty years the Empire has become full of foreigners. They have divided the land. The Kwo-wen-pao [Guowen bao, a Chinese newspaper] always talks nonsense about the 'Boxers,' since it is under the protection of Japan. We remind the Editors that hereafter they must not talk nonsense; if they continue to do so their building will be burnt. The Brethren need not fear ... When the foreigners are driven away, we will return to our hills! Source: As quoted in Rev. Z. Chas. Beals, China and the Boxers, Munson, New York, 1901, p. 15 Questions 18 What do you think this poster is suggesting about the relationship between the Boxers and the Emperor? Why do you think the writers of this poster are trying to make this association? 2 Why is this poster critical of the Chinese newspaper, the Kwo-wen-pao? If you were investigating such claims, what would you need to do in order to assess their reliability? List your suggestions. 3 In what ways does this poster attempt to show the determination of the Boxers to succeed and to reassure their supporters that they do not simply want power for themselves? 4 Do you consider this poster to be a reliable source of information about the Boxer uprising in Beijing? Explain your view. Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia The siege of the legations seriously frightened the powers. It led to an unprecedented event. Normally the imperialist powers were at loggerheads and competing with each other. But eight of them united to send troops to defeat the ragged Chinese peasants who made up the Boxer army. The eight were Britain, France, Germany, Russia, Italy, AustriaHungary, the USA and Japan. In the summer of 1900, they advanced on Beijing to end the Boxer siege and to defeat and expel the Boxers. The Qing Imperial Court was divided over what to do in the face of this crisis. Many of the courtiers supported the Boxers because they were prepared to make a stand against the foreigners. But the anti-Boxer courtiers gained the upper hand as time passed and the situation grew worse for China. The day after the siege was lifted, the Imperial, Court, including both the Empress Dowager and the Emperor, fled the capital to set up the Court in Xi'an, capital ofShaanxi province, to the south-west of Beijing. Document 1.12 20 Illustration of the Court fleeing from Beijing Source: Rev. Z. Chas. Beals, China and the Boxers, Munson, New York, 1901, p. 101 Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia 4 Why do you think that the individual or group responsible for producing this poster displayed it by the roadside? 5 How reliable might this anonymous source be as an item of evidence about the Court's flight to Xi'an? Discuss your view with another student. .......... The Boxer protocol and Western views of the situation in China After the defeat of the Boxers, the Empress Dowager and her Court returned to Beijing, arriving there early in January 1902. Meanwhile, China had been forced to sign what was possibly the most humiliating of all agreements with the foreign powers: the Boxer Protocol of September 1901. Under this arrangement, China agreed to pay a gigantic indemnity, meaning, in effect, that it had to pay to be invaded. Furthermore, it had to open up several more cities as treaty ports and even had to deny Chinese people the right to reside in the legation quarter. The following comment was written before the outcome of the Boxer Protocol was known. It had earlier been suggested that even harsher terms than those of the Protocol should be imposed on China. Many in the West thought China would fall apart, and some even hoped that it would. Document 1.14 22 A missionary's view of the situation in China after the suppression of the Boxers The greatest living issue before the church and the nations today is the Chinese question. At last China - conservative, secluded, selfish, heathen China - has overstepped herself, and forced upon herself either the permanent dictation of the more civilised nations or dismemberment. Which horn of the dilemma she will choose it is impossible to forecast at present. Whether the settlement with the allied powers is near at hand, or, if so, whether it will be satisfactory, sufficient and wise, is problematical. .. In due time the clouds hanging over China will be dispelled, the ancient nation will have been thoroughly scourged, she will enter upon a new lease of life, chastened and humbled; her doors will be thrown wide open to civilisation, commerce and Christianity, and her four hundred millions of people will stand on the same plane as those of the other nations, and from this great seething mass will come a great multitude, a mighty army, to swel 1 Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia far in the future by dismemberment, partition, and the industrial dominance of the men of the living nations. Source: As quoted in Rev. Z. Chas. Beals, China and the Boxers, Munson, New York, 1901, p. 152 Questions 1 Which of the following statements do you consider best sums up the editor's attitude to the situation in China? a The editor is sympathetic to the Chinese. b The editor is contemptuous of the Chinese. c The editor considers that Western intervention in China is inevitable. d The editor believes that the Chinese will rule themselves. Explain your choice. 2 Choose extracts from the document that best support the following statements: a The people of China are incapable of ruling themselves. b The industrialised West will determine China's future. c China is not advanced when compared with the West. d China will benefit from Western intervention. Write out the extracts next to the corresponding statement in your notebook. Of the extracts you have chosen, which do you consider best indicates a Western imperial view? Explain your choice to another student. Evaluations of the Boxers in later times Despite the disastrous defeat inflicted on the Boxers, they occupy a significant place in the history of Chinese nationalism and opposition to imperialism. Here are two accounts, written after the event, that relate to the Boxer uprising. Both recognise the patriotism of the Boxers. Whilst neither actually uses the term nationalism, its significance is implied in both. Nevertheless, each reaches an extremely different verdict on the Boxers and their impact on Chinese history. Document 1.16 A People's Republic of China view of the Boxers' historical significance The Yi Ho Tuan Movement [Boxer uprising], which broke out in China in 1900, shook the whole world. It was a patriotic anti-imperialist uprising, mainly of peasants. It was a product of deepening imperialist aggression, and of unprecedentedly aggravated national crisis ... China's working class had not yet mounted the political stage. The masses -24 China I: The Late Qing Dynasty of the people, with peasants as the main body, organised themselves to resist and fight crime-laden imperialism. It was they who felt most deeply, in their everyday life, the heavy weight of imperialism. After the Sino-Japanese War of 1894 the Chinese [Qing] government, in order to pay the huge war indemnities and foreign loans, heightened its exploitation of the people. Moreover, foreign missionaries who wore the cloak of religion but actually served imperialist aggression had for some time been penetrating China's cities and countryside, building churches, lording it over the people and committing many crimes. Driven beyond tolerance, the people had waged struggle against the missionaries since the 1860s and 1870s, and this movement surged up everywhere in the 1890s ... The rapid rise of anti-missionary struggles heralded the anti-imperialist revolutionary storm. 152 Source: Compilation Group for the 'History of Modern China' Series, The Yi Ho Tuan Movement of 1900, Foreign Languages Press, Peking (Beijing), 1976, pp. 1, 12-13 Questions According to this source, which class of Chinese society made up the Yi Ho Tuan Movement? 2 How does this source explain the motivation of the Boxers? 3 Which particular group is singled out for the most criticism in this document the imperialist aggressors, the Qing government or the foreign missionaries? Suggest an explanation for this and justify your response. 4 Keeping in mind that this view of the Boxers' historical significance was published in 1976, in what ways might this interpretation of the Boxer uprising be: a representative b reliable c biased d inaccurate? Explain your reaction to each of the above, then indicate which you consider to be the most appropriate evaluation of this source as an item of evidence abou~t the Boxer uprising. The other account, written in the 1930s, comes from the pen of Reginald Johnston (1874-1938). He was a British colonial official, scholar, writer, a great admirer of Chinese culture, and was personal tutor to the last of the Manchu emperors, Puyi. Johnston remained a supporter of the imperial system of government, but was very critical of the Empress Dowager and other individuals who represented it. He has become well known in recent years through his portrayal in Bernardo Bertolucci's magnificent film The Last Emperor, released in 1987. - 25 China I: The Late Qing Dynasty Reform and nationalism in the Qing dynasty's last decade One of the effects of the Boxer uprising was to force the Qing government to make greater efforts at reform. The first decade of the twentieth century saw an enormous degree of change and revival in China, even including constitutional reform. The Empress Dowager herself was forced to pay lip service, at least, to the notion that China must reform and modernise itself, and she became a supporter of ideas she had strongly resisted not long before. In November 1908, the Empress Dowager died within a day of the Emperor's death. She had tried for many years to dominate both her nephew and the Chinese state, and had succeeded most of the time. But a new era was beginning. One of the most far-reaching changes was made in 1905 with the abolition of the traditional examination system through which officials had been selected over many centuries. The system of training officials was thoroughly changed in one blow. So was the kind of education society believed its administrators and leaders needed for the effective running of the state. The elite of society would no longer depend on Confucian education, but on more modern and Western-oriented training. The reforms of the twentieth century's first decade failed to save the Manchu dynasty. Yet their significance within the context of their own times should not be ignored. The Manchus should be given credit for their attempts to come to terms with the disaster the imperialists had imposed on them. Writing about the impact of the reforms of the last decade of the Qing dynasty, the late American scholar Mary Wright (China in Revolution: The First Phase, 1900-1913, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1968, p. 1) has written, 'Rarely in history has a single year marked as dramatic a watershed as did 1900 in China.' ,,. The various crises that befell China in the years leading up to and including 1900 gave rise to a powerful nationalist spirit. This had a strong impact both on intellectuals and ordinary people. One of the most important of the intellectual leaders was Liang Qichao, whose leading role in the reform movement of 1898 has already been mentioned. He was amongst the first of all Chinese thinkers to develop ideas of nation and nationalism. The following passage gives some idea of his thinking. . . . . . . . .. . Document 1. 18 Liang Qichao on nationalism Since the sixteenth century, some 300 years ago, the reason why Europe developed and the world progressed was because of the impetus created by widespread nationalism. What is this thing called nationalism? It means that, no matter where you are, people of the same race, the same language, the - 27 Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia same religion and the same customs regard each other as relations, work towards independence and autonomy, and organise a better government to work for the public good and to oppose the onslaughts of other nations. When this idea had developed to an extreme at the end of the nineteenth century, it went further and became national imperialism over the last twenty or thirty years. What does national imperialism mean? It means that the power of a nation's citizens has developed domestically to the stage where it cannot help but press outside, so that they industriously try to extend their powers to other regions. The ways of doing this are through military power, commerce, industry or religion, but they use a co-ordinated policy for guidance and protection ... Now on the eastern continent there is located the largest of ·countries with the most fertile of territory, but the most corrupt of governments, and the most disorganised and weakest of peoples. No sooner had those races [from Europe] found out about our internal condition than they got their socalled national imperialism moving, just as swarms of ants attach themselves to what is rank and foul and as ten thousand arrows focus on a target ... If we want now to oppose the national imperialism of the powers [effectively], rescue China from disaster and save our people, we have no choice but to adopt the policy of pushing our own nationalism. If we are serious about promoting nationalism in China, we have no option but to do it through the renewal of the people. Source: Yinbing shi quanji (Complete Works of Liang Qichao), vol. 1, China Bookshop, Shanghai, 1916, pp. 3b, 4a-b (translation by Colin Mackerras) Questions 28 How does Liang Qichao define nationalism? 2 According to Liang Qichao, what is national imperialism? 3 Do you think that Liang Qichao values nationalism as something worthwhile, or does he see it as the means to an end (the most practical way for China to oppose Western powers)? 4 What do you think Liang Qichao means in the last line when he refers to the . 'renewal of the people'? 5 Which of the following terms might best describe Liang Qichao: a a realist b a reformer c a patriot d a reactionary e a nationalist? After you have made your choice, write a brief justification of your decision an explain it to another student. Nationalism had clearly become a substantial force by the first decade o the twentieth century. Chinese anger was felt both against the Manchus China I: The Late Qing Dynasty who still dominated the Qing dynasty, and against the Western powers. The invasion of the eight powers against China made many in China believe that their country was about to be reduced to the status of a colony, as the following poem indicates. The author of the poem, Chen Tianhua, killed himself as a protest against the Qing dynasty's repression of nationalist students. .... . .. . .. Document 1.19 A patriot's fear of colonialism All we want is to recover our land and they say that is rebellion! It is the shameless ones who would fight for them! We are only afraid of being like India, unable to defend our land; We are only afraid of being like Annam, of having no hope of reviving ... We are only afraid of being like the Jews, the Jews who are without a home! We Chinese have no part in this China of ours. This dynasty exists only in name! Being slaves of the foreigners, They force us common people to call them masters! solves : ers no ;care do Source: As quoted in C. T. Liang, The Chinese Revolution of 1911, St John's University Press, Jamaica, New York, 1962, p. 12 1, Questions 1 According to this poem, in what ways are the Chinese the 'slaves of the foreigners'? 2 Refer to your own general knowledge about Western imperialism and to the poem to answer these questions: a Which of the eight Western powers occupied India and Annam (Vietnam) 9t this time? '-. b How might knowledge of what occurred in these nations have alarmed the Chinese? c In what ways might the poet's reference to the Jews stimulate a nationalist response from the Chinese who read it? 3 How reliable and representative could this poet's sentiments be regarding the fear of colonialism amongst the Chinese? 1 nd ;of s, The most important of the Chinese nationalists of the late Qing dynasty was undoubtedly Sun Yatsen. Beginning from 1895, he led a series of revolts against the dynasty. Ironically, he was strongly influenced by the West despite his nationalism and was trained there as a doctor. He had many Western sympathisers with his nationalist aspirations, as well as many Chinese supporters living outside their own country. In 1911, while Sun was overseas and far from the action, an uprising erupted in the central - 29 Imperialism, Colonialism and Nationalism in East Asia southern city ofWuchang, which succeeded very quickly in bringing about the total collapse of the Qing dynasty. On 25 December 1911, Sun Yatsen arrived back in Shanghai and on 1 January, exactly a week later, was inaugurated as President of the Republic of China. Within six weeks, the Emperor issued an 'edict of abdication'. The centuries of the imperial system of government in China, which had seemed so necessary and invincible, were finally at an end. Later Chinese leaders' views of imperialism We shall see in the next chapter that Chiang Kai-shek was leader of China from 1927 to 1949 and an ardent follower of Sun Yatsen. He was also a man with strong views on Chinese history and on the West's role in it. In the following passage he does not actually use the term 'imperialism' or 'imperialists', but certainly did so in others, showing that he was prepared to equate the experience of nineteenth-century Europe with imperialism. Document 1.20 30 Chiang Kai-shek's summation of imperialism For the last hundred years Western science has greatly benefited Chinese civilisation. This cannot be denied. After the Opium War, in the belief that the Western powers were rich and strong because of their guns and ships, the Chinese people began to study the technique of making guns and ships. After the War of 1894, the Chinese people also began to study foreign social and political institutions. Famous works of Western social science were translated into Chinese. Discussion of Western social and political theories began to appear in magazines and newspapers. For several decades after this, as a result of discussion, popular study, comparison, and observation, China's applied science, natural science, and social science all made progress. In some fields, we even made important new contributions to human knowledge. The power and prestige of science was fully recognised in Chinese thought and learning. On the other hand, during the past hundred years, China's civilisation showed signs of great deterioration. This was because, under the oppression of the unequal treaties, the Chinese people reversed their attitude toward Western civilisation from one of opposition to one of submission, and their attitude toward their own civilisation changed from one of pride to one of self-abasement. Carried to extremes, this attitude of submission became one of ardent conversion and they openly proclaimed themselves loyal disciples of this or that foreign theory ... We should bear in mind that from the Opium War down to the Revolution of 1911, the unanimous demand of the people China I: The Late Qing Dynasty was to avenge the national humiliation and make the country strong, and all efforts were concentrated on enriching the country and strengthening the army. Source: Chiang Kai-shek, China's Destiny & Chinese Economic Theory, Roy Publishers, New York, 1947, pp. 96--7 Questions 2 3 4 5 According to Chiang Kai-shek, in what ways has Western science benefited Chinese civilisation? How does Chiang explain the change in attitude by the Chinese people towards the West, and what does he see resulting from this? Choose some extracts from Chiang's account that might illustrate: • Western imperialism • Chinese nationalism. Copy the relevant extracts next to the correct term. Share your response with another student. How reliable might Chiang's views be as an item of evidence about the Chinese response to the West? Consider Chiang's position in Chinese history. What might have motivated him to record such views? During the period Chiang Kai-shek ruled China, his main enemy was Mao Zedong, the leader of the Chinese Communist Party. On the whole, Chiang's policies were considerably more conservative than Mao's. So, Mao's more forthright view on the role of imperialism in China's recent history is not surprising. . .. . .. . . . . Document 1.21 \. Mao Zedong's overall view of imperialism Imperialism occupies the principal position in the contradiction in which China has been reduced to a semi-colony, it oppresses the Chinese people, and China has been changed from an independent country into a semicolonial one. But this state of affairs will inevitably change; in the struggle between the two sides, the power of the Chinese people which is growing under the leadership of the proletariat will inevitably change China from a semi-colony into an independent country, whereas imperialism will be overthrown and old China will inevitably change into New China. Source: Mao Zedong, 'On Contradiction', Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung [ZedongL Volume I, Foreign Languages Press, Peking (Beijing), 1965, p. 334 - 31