here - City College Plymouth

advertisement

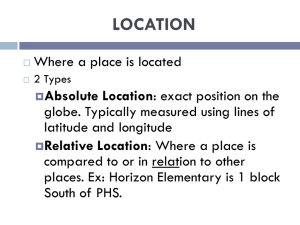

The History of City College, Plymouth 1887-2013 John Van der Kiste View from Innovation Building towards Plymouth Sound Contents Part One to 1974 1 Part Two 1974 to 1985 10 Part Three 1986 to 2013 16 College Development Milestones 32 References33 Bibliography34 Pa r t 1 One to 1974 Devonport Annexe, formerly Devonport Technical College for Science and Arts In 1887 the Mayor of Plymouth, Mr W.H. Alger, called a public meeting to consider ways by which the town council could celebrate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. It was decided that contributions should be collected for the Imperial Institute in London, and also for a separate local memorial, the form of which would be decided by a special committee. Members of the latter agreed the local Jubilee memorial should take the form of raising a fund for the establishment of a Science, Art and Technical School, in cooperation with the Town Council. Part of the old cattle market site at Tavistock Road was given by the Corporation for the purpose, and on 30 September 1889 the two limestone foundation stones of the ‘Victoria Jubilee Memorial Science, Art and Technical Schools’ were laid. Three years later the building was completed and the schools opened for a winter session of university extension lectures. A civic ceremony on 7 October 1892 marked the official opening of the Schools and the formal transfer of the buildings, built at a cost of £5,400, from the care of the Jubilee Memorial Committee to their new owners, the Town Council. The basement contained the carpenters’ shop, plumbers’ shop, mechanical and electrical engineering shop with gas engine, dynamo and screw-cutting lathe, plus rooms for cookery lessons, wood-carving and casting. On the first floor was a drawing office for machine and building construction, physics laboratory, lecture theatre with preparation room, mathematical and other classrooms, an elementary art room, committee room and offices. On the second floor were the chemistry laboratory, lecture room for physiology, hygiene and chemistry, dressmaking room, large antique room, life room and modelling room. 2 Artisans, clerks, teachers and other employed persons needing further education in science and art subjects could attend evening classes for a small fee. Classes in mechanical and electrical engineering, plumbing, carpentry, typography, dressmaking and woodwork were held up to City and Guilds standard. Instruction in chemistry, physics, biology and pharmacy were recognised by the Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons, and medical students could complete their first year’s examination locally home. In the year 1898-9 800 students attended, under Mr J Burns Brown, BSc, Head Master of the School of Science and Technology, and Mr Frederick Shelley, ARCA, Head Master of the Art School. In 1899 the Town Council approved an extension which was completed four years later. Inspired by Plymouth’s example, in 1892 Devonport Borough Council nominated a Technical Instruction Committee to report on existing Science and Art classes in the Borough, and to seek suitable premises in which to coordinate and extend these classes. Rooms at 38 George Street, Devonport, were leased for five years at an annual rent of £65 while the Council negotiated with the War Department to purchase a plot of ground three-quarters of an acre near Devonport Station. Recruitment for students began in September 1893. 425 students were registered for lessons applicable to the trades and industries carried on within the Borough, and lessons began on 18 September 1893. As the premises soon proved inadequate, the Technical Instruction Committee decided a permanent building was required. The lowest tender received for the construction was £13,268. 3 The foundation stone of the Devonport Municipal Science, Art and Technical School in Paradise Road, Stoke, was laid on Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Day, 22 June 1897. In the centre of the north wall, opposite the main entrance, was a stained glass window representing the development of naval architecture during the career of Sir William White, a former dockyard apprentice who became Director of Naval Construction and was elected a Freeman of the Borough that same day. Two years later the completed building was opened. A plaque is accordingly inscribed: The erection of this school building was commenced in the year 1897 in commemoration of the 60 years glorious reign of Her Majesty Queen Victoria and on completion, was on the 25th Day of July 1899, duly inaugurated and dedicated to the public use and benefit by the Right Worshipful Mayor W Hornbrook Esquire in the presence of and with the assistance of Sir William H White, KCB, LLB, Dr. Sce, FRS The basement housed rooms for mechanical engineering, woodwork, a clay-modelling room, plumbers’ workshop and the building’s engine and boiler room. On the ground floor were five classrooms, a large lecture hall doubling as a room for technical drawing, a committee room and the secretary’s office. Chemistry and physics laboratories and a lecture room were at the west end of the first floor, with three art rooms and a commercial room at the eastern end. Classes were held in connection with the Science and Art Department, the City and Guilds of London Institution, the Society of Arts and the Worshipful Company of Plumbers. About 80% of the students on the mechanical science courses came from the dockyard. Between 1898 and 1936 the Paradise Road building also housed the Devonport Municipal Secondary School for Girls, which subsequently moved into separate premises in Outland Road. 4 The Plymouth Science, Art and Technical Schools, Tavistock Road, opened 1892 The Plymouth Science, Art and Technical Schools, Tavistock Road, opened 1892 Devonport Technical School The The Plymouth Science, Art and Technical Schools, Tavistock Road, opened 1892 5 Devonport Railway Station, 1927, demolished 1971 6 In 1914 the Three Towns (Plymouth, Devonport and Stonehouse) formally amalgamated. The two schools, the Victoria Jubilee Schools and Devonport Technical College for Science and Arts, followed suit, and were henceforth known as the Plymouth and Devonport Technical School. In 1926 it was designated a college, and in 1932 it absorbed the Plymouth School of Navigation. This had been founded in 1862, initially located in Gascoyne Place and moved to Durnford Street around 1908, but attendance slumped during the economic crisis of 1931. As a result it became part of the Mathematics and Physics Department of the Technical College. In November 1951 work began on building a new, greatly enlarged college. The foundation stone was laid in May 1952, and the new Technical College, Glanville Street, was opened in March 1955 by Dr Alexander Fleck, Chairman of ICI. According to the souvenir programme, it promised to be "only the first instalment of a plan for a new Plymouth Technical College which will eventually extend over an area bounded by Tavistock Road, James Street, Coburg Street, and the northern side of Portland Square."1 The original building comprised four floors. Additional workshops, laboratories, an enlarged library, refectory and other facilities were built from 1960 onwards. In 1962 the College became Plymouth College of Technology, one of only 25 such regional colleges in the country. In May 1966 the Government produced a White Paper, 'A Plan for Polytechnics and other Colleges'. As a result of subsequent legislation a limited number of authorities, one of which was Plymouth, were invited to offer themselves as 'centres of excellence'. The Local Education Authority and the City Council agreed to this and to take steps to create a Polytechnic within the City, to provide higher education courses of degree, diploma and similar standards for students aged 18 and above. This would entail the large volume of less advanced work being separated from the Polytechnic type of work and transferred to a College of Further Education, organized and administered as a separate entity. 7 Approval for building a new College within this remit was given in October 1967, and the City chose a site at Kings Road opposite Devonport Technical College, a 10.7 -acre triangular area previously occupied by the Devonport Southern railway station which had closed in 1964. Tunnels from this time still exist under the site. It was purchased from British Rail as part of a package deal costing £7,500. Six months later the City was required by the Department of Education and Science to reduce expenditure by 10 per cent. Next month the project was cut out of the 1968-69 building programme, and authorisation for starting the College was not confirmed until November 1969. Plymouth College of Technology officially ceased to exist on 31 December 1969. After that university level courses were transferred to the Polytechnic, and all the others to the College of Further Education. The latter was designated to cater for a variety of fulltime, part-time and block-release courses, covering training over a range of craft and technician skills leading to National Certificates and Diplomas. The first Principal of the College, William (‘Bill’) Foster, formerly Deputy Principal of Coventry Technical College, took up his appointment in May 1970. The College Prospectus for the 1970-71 session listed six Departments, namely Commerce and General Studies; Construction Studies; Electrical Engineering; Mechanical Engineering; Maritime Studies; and Science. Due to delays in acquiring the Kings Road site and starting the building work, the College lost its place in the Department of Education & Science ‘starts’ list for that year. As a result of strong representation on the part of the local authority, and visits by the inspectorate early the following year, the situation was soon rectified. Nevertheless, for a time the College operated from 35 different annexes scattered throughout Plymouth, with administrative headquarters in the Polytechnic building. Some staff, and accommodation, were shared by the College and Polytechnic. 8 The annexes included Sherwell Church Hall, adjacent to the Polytechnic (Physics and Chemistry lectures), King Street Church Hall (Mathematics and Computing), Devonport Annexe, Paradise Road (GCE 0 and A levels); Durnford Street (Radio Officer classes); and Prince Rock (Automobile Engineering). By November 1970 the College had 4,000 students, 140 full-time teaching staff, clerical, technical, technician and part-time teaching staff. In the following year it was amalgamated with the Dockyard Technical College. In January 1972 work on building the new College was begun, overshadowed by the uncertain economic climate and objections from residents of Albemarle Villas at the siting of a new college near their homes. It was initially expected to be ready for occupation in late 1973, but delays resulted in opening a year later than scheduled. For students and staff (5,728 students and 190 full-time lecturers in early 1972), the premises could not be completed soon enough. A report in the press of February 1972 painted a semi-Dickensian portrait of marine radio officer students working in the attic and basement of a four-storey Georgian terraced house in Durnford Street; other students from the former College of Technology were housed “in makeshift accommodation in church halls, disused beerbottling plants, a former convent, obsolete schools, a cluster of huts.”2 Their studies were generally carried out in premises overcrowded with machines, with outdoor toilet facilities, canteens and common rooms falling far short of statutory minimum requirements, and the frustrating time-wasting element involved in travelling between annexes for different lectures. A decision to incorporate the College of Domestic Science into the College, adding two new departments, Hotel, Catering and Institutional Management, and Community Studies, and a directive that the local authority must assume responsibility for the Devonport Dockyard technical school students, almost doubled the original projected cost of the new college. The final figure was estimated at almost £4,000,000, in addition to the interim expense of retaining the annexes at a probable total cost of £250,000. 9 Pa r t Tw o 1974 to 1985 10 IN SEPTEMBER 1974 the Kings Road eight-storey tower block, Phase I, was officially opened. The College was now able to move out of the mechanical and electrical engineering areas in the Polytechnic, withdraw from use of the HM Dockyard Apprentice Training Centre, and close some of the annexes. With 8,000 full-time and part-time students, it was claimed that the College was now operating in purpose-built accommodation which had no equal this side of Gloucester.3 The block was flanked by the refectory, library and administration offices, and abutted at the back by single-storey workshops. On the occasion of its opening, Mr Foster promised that the College would be used partly as a community centre with some facilities, including the assembly hall and refectory, being made available to local residents as well as to staff and students. "While a college of this type is normally associated with vocational studies - preparing people for careers or assisting them with jobs they already hold - nevertheless an institution of this nature has an increasingly important part to play in the non-vocational - recreational - field and in local community activities."4 The Phase II buildings came into use in April 1975, enabling the College to withdraw completely from the Polytechnic premises, and close some annexes, wherever possible those furthest away from the main Kings Road site. Nevertheless, even at this stage only 40% of the College was thus concentrated. 60% of the teaching and work of the College was still carried on in the 16 scattered annexes, several of which were in poor condition, with defects such as leaking roofs and heating breakdowns. W B. (Bill) Foster, Principal 1970 - 1988 11 Despite the inconvenience, the building work in progress had its lighter moments: “A temporary, thin wall separating the Phase I 'usable' Library from the Phase II 'in building' section of the Library did little to restrict noise and dust, particularly when air hammers were operating. Instructions shouted to workmen on one side were - occasionally - obeyed or replied to by students on the other! The temporary walkway through the central pool area enabling students to reach the Refectory worked well - most of the time - but several immersions in the pool did result. Student cars did become mixed up with the contractors' lorries and vice versa. Students were asked where sand was to be delivered - and lost no opportunity in providing bizarre answers!" 5 By November 1975 the College was free of contractors’ staff. During the academic year September 1974-July 1975, 8,800 students had been enrolled, of whom 1,750 were fulltime and sandwich. In the subsequent year September 1975-July 1976, 10,251 students were enrolled. Of these 2,128 were full-time and sandwich, 4,196 were on day or block release courses from local and regional industry and commerce, 2,970 evening-only and short course students, 307 correspondence course students and 650 children on link (attending some lessons at the College) and sampling (secondary students visiting the College to watch work in progress with a view to helping them select a career) courses from local schools. Additional plans for the College’s consolidation, including a second tower block, were placed on hold because of the difficult economic situation. Financial constraints and cuts in public expenditure, for example, meant that in September 1976 no classes with fewer than twelve enrolments were allowed to start; sampling and link courses were stopped; and student course hours were reduced. The number of students seeking full-time places was far in excess of the places available. Non-vocational courses were hit hardest, but effects were also felt in the vocational fields and in some cases a strict rationing 12 of places was inevitable. It was a regrettable fulfillment of the prediction that “the College did not meet the demands placed on it by the community and was not able to do so because the resources which it needed were not available for it.”6 Contrary to previous practice, enrolment ceased after the start of the academic year, so that no classes would be enrolled at Christmas.7 The number of students dropped from 10,250 in September 1975-July 1976 to 9,700 in September 1977-July 1978. During the next academic year, September 1978-July 1979, student numbers rose to 10,750. Of these, 2,460 were full-time or sandwich, reflecting an 18% increase over the previous year. 3,773 were ‘on release’ from local industry and commerce for ‘full part time day or part time day/evening courses’, reflecting a 4% decrease upon the previous year which was itself a decrease upon 1976-77. The lesson was noted that industry and commerce were not taking on apprentices or trainees to whom they had to give day or block release over several years.8 Enrolment in September 1980 established what was coming to be seen as ‘the norm’, a rise in full-time students, particularly those under 18, and a drop again in part-time. At a time of commercial and industrial recession, with employers not taking on such a large labour force, and with automation meaning output could be maintained with a lower work force, in the absence of jobs it was anticipated that young people would look to college education to provide them with skills and education to make them more attractive to the labour market. Nevertheless other factors were emerging, causing full-time attendance to be regarded positively, and not just as a refuge from the lack of jobs. Employers realized increasingly that a full-time product was partially or wholly trained, at no direct expense to them, and immediately usable in the work situation, thus usually needing no further ‘release’. Young people were quick to appreciate this, and an increasing number now arrived direct from school without looking into the labour market.9 13 At one stage, it was feared that completion of the main building at Kings Road was unlikely in the foreseeable future, and plans were put on hold for some years. Fortunately, policies for expansion in other directions proved more fruitful. In 1973 it had been suggested that a School of Chiropody was needed to serve the needs of the south west. Plymouth was regarded as the best site, and a firm proposal was submitted to the appropriate educational and medical authorities in July 1977. In September 1980 the School of Chiropody, initially part of the Department of Science & Mathematics, came into being at North Road, the only such establishment in the westcountry. 19 students were enrolled for the three-year course from the 40 applicants interviewed, patients were accepted for treatment from the beginning of November, and the School was officially opened the following month by the President of the Society of Chiropodists.The first intake of students who completed the course in June 1983 achieved a 100% pass rate. Completion of the new Hotel and Catering block (which was to result in the long-overdue closure of the antiquated 1940s-built premises at Portland Square) was approved in 1980 at a cost of £2,250,000. The foundation stone of the new building was laid in April 1982, and the premises opened in October 1983. As a result the College was ideally placed to take advantage of growing interest in all aspects of the hotel and catering sector, including vegetarianism, being the first in the country to offer a two-year diploma course in Vegetarian Catering. The School of Maritime Studies merged with the Polytechnic faculty in September 1984. For several years this had provided the only example of ‘joint usage’ between the College and the Polytechnic. Within a few years, as a result of subsequent contraction in the industry, maritime courses were no longer offered in Plymouth. 14 By the mid-80s the College was well established as the major local provider of vocational education for a catchment area extending as far north as Tavistock and as far east as Ivybridge, as well as east Cornwall. The establishment of the Saltash annexe to the Mid Cornwall College of Further Education in 1984/85 somewhat diminished the latter role. It had also become a regional centre for a number of courses in electronics and certain construction and business specialisms, and enjoyed national recruitment in chiropody, supervisory management and some catering courses. Overseas students were recruited into a number of courses, and direct links for student exchange were forged with educational establishments in France, Germany and Holland within the areas of hotel and catering and electrical engineering. Aerial view of the College 15 Pa r t Three 1986 to 2013 16 IN MARCH 1986 a team of H.M.lnspectors carried out an inspection on behalf of the Department of Education and Science as part of a national exercise covering non-advanced further education in England and Wales. The working party spent five days in the College observing classes, meeting staff and students and inspecting accommodation and facilities and their report, published in October 1987, provided a detailed 'snapshot' of the College. Part 1 was divided into reports on the origins of the College and its socio-economic context; College aims, organisation and management; Accommodation and resources; Courses; Staff and staff development, Students, Teaching and learning; and Links with industry and commerce. Part 2 examined the ten departments existing at the time in detail. In its summary, the report maintained that "Overall the college is efficiently managed. Clear aims and objectives have been set for the college as a whole and the management system at senior level is operating effectively and efficiently in pursuit of these goals ... Academic and course development as well as resource management are rooted firmly in a clearly defined departmental system. Though this system has served the college well in several respects there is some scope for considering whether it can meet the future needs of those areas of the curriculum and management which demand ‘cross disciplinary and cross college’ co-operation and development.”10 It also commented on the unsatisfactory state of some College accommodation - particularly the poor condition of annexes at Sutton and Wyndham Street - and its effect on the standards of teaching and learning achieved, as well as on the morale of staff and students. Also highlighted were the urgent need for improvement and updating of the level and standard of some equipment and resources, particularly in Mechanical Engineering and Computing; innovative and valuable developments in the provision of Euro-courses in Hotel and Catering, and in Open Learning courses; the need for the development of an overall College policy on welfare and guidance, to ensure that all services available to students were used effectively; and the links between departments and local industry well established over 17 the years, which would benefit from more effective overall mechanisms for marketing its courses, developing new ones, and for monitoring changing needs as well as performance. Employment trends in Plymouth, it noted, had followed national patterns, with a decline in the traditional engineering, motor vehicle and construction trades and corresponding growth in the service areas of catering, business studies, social services, and above all in the new technologies of microelectronics and information processing. Similar observations were shortly to be made in a history of the city published in 1991, referring to a new climate as regards education and employment: “...its [the College’s] intake fluctuates because the provision of courses reflects changes in the local labour market and local needs. In general, this has reflected the decline of traditional heavy engineering and craft-based employment in the vicinity and the move towards service industries. In addition, there is a trend towards more young people seeking qualifications; whereas the majority used to leave school unqualified in the 1960s, only 13% of boys and 9% of girls did so nationally in 1988. In the FE sector this means that there are now more classes for A levels and for subjects such as catering, computing and office skills. The introduction of Business and Technician Education Council (BffEC) courses, Youth Training Schemes (YTS) and now more generalised National Vocational Qualifications, has meant a move towards national validation of courses in further education. Nearly all young people are able to gain a qualification in some field in the 1990s, and there is an increasing range of vocational awards as well as academic ones as a result of efforts to build links between education and employment.” 11 18 During the academic year 1986-87, extensive reorganisation within the College took place. To quote the Principal’s Report for that year, “Further Education in general has now accepted that stability is a luxury which will be rare in its appearance. Nationally the variations in demands, ideas and ‘initiatives’ from the Manpower Services Commission together with the changing attitudes of validating or examining bodies, the emergence of the National Council for Vocational Qualifications (NCVQ), the launch of the Open College, the emphasis upon Access and INSET all create a fluid backcloth with no guarantee of even short term stability. Against this backcloth and superimposed upon it are the local changes and varying demands. Within the College ... two Assistant Principals appeared, seven of the nine Departments disappeared - and the other two changed in character - six new Departments appeared, two Heads of Department left the College and four new ones arrived. There were massive staff movements within Departments and new allegiances had to be formed.” 12 Guardino (Ross) Rospigliosi, Principal 1988 - 2000 19 The old Engineering (Electrical and Mechanical) and Construction Studies Departments were merged into a newly formed Faculty of Technology. It was now responsible for running courses in the broad fields of Construction, Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Mechanical and Production Engineering and Computer Aided Engineering, and absorbed the Department of Information and Computer Technology from the old Science and Mathematics Department. Also affected by major upheavals was the old Humanities Department. A large part of its work - the GCE, CPVE and General Studies programmes - joined with much of the old Department of Science and Mathematics to become the new Department of General and Tertiary Studies. Modern Languages, Physical and Leisure Studies and Social Studies joined with the old Community Studies Department, to become the new Department of Personal and Community Services, to which was added the Caring programme from the old Vocational Preparation Department. The new Department was relocated at two new annexes, Stoke Damerel and Albert Road. Travel and Tourism Studies was shared with the Hotel Catering and Institutional Management Department. In July 1988 Mr Foster retired as Principal of the College. He was succeeded by Guardino (‘Ross’) Rospigliosi, formerly Principal of Richmond-on-Thames Tertiary College and was subsequently awarded the OBE in the 1989 new year’s honours for services to education. In retirement he maintained his involvement with various national education committees. He died in February 2011, aged 82. In October 1990 it was announced that a major job-training centre for Plymouth would be set up within Devonport Dockyard. The College would take over the running of the yard’s training centre in Goschen Yard at Saltash Road, 1.3 miles from Kings Road, using it to train dockyard apprentices as well as engineering and computing students, and it was proposed to transfer the Faculty of Technology there. A 21-year lease for the yard from the Ministry of Defence was secured by the College in June 1993, and £2,000,000, of which half was provided 20 by a European Regional Development Fund grant, was spent on converting the buildings. A government statement in March 1991 announced the establishment of a new independent sector of post-16 education. All maintained Further Education Colleges providing full-time education, including Tertiary and Sixth Form Colleges, would be taken out of local authority control with effect from 30 September 1992. From that date, the College ceased to operate as part of Devon County Council. Full financial separation came on 1 April 1993. By the end of the academic year 1993-94, Plymouth College of Further Education had around 20,000 registrations/enrolments, 4,500 full-time equivalent (FTE) students, actually 12,500 people studying, equivalent to about 5% of the population of Plymouth. The teaching was still scattered around six annexes. When the new centre at Goschen Yard opened in September 1994, four (all but the one at Devonport, opposite the Kings Road site, and North Road) closed. These last two sites closed a few years later, and Devonport Annexe was converted into flats. The original plans for Goschen Yard had changed in nature by then. It became a Centre of Excellence for academic, A-levels and GCSEs and caring courses. The Faculty of Technology was installed at Kings Road, which also housed the Department of Hotel, Leisure & Beauty, the Department of Construction Studies, the Department of Open & Flexible Learning and the Plymouth Management & Business Centre. Courses offered at the College vary in length from one day to six years, covering the full spectrum from learning difficulties to postgraduate, with a range of options in addition to full-time and part-time, including drop-in provision at the Open Access Centre and Open Distance Learning programmes. 21 The Goschen Centre 22 It was noted in 1996 that over 600 Plymouth CFE students had progressed to higher education in the previous two years; and that of those former students for whom records had been kept, only 3.3% were registered as unemployed, compared to 9.9% in June 1995 for the Plymouth travel to work area. Moreover a further inspection of courses and resources by the Department of Education & Science, conducted over a period of 15 months and completed in May 1996, placed the College in the top ten in England for cross-college grades based on the results published to date. It scored Grade 1, the highest possible, in responsiveness and range of position; equipment and learning resources (less than 10% of colleges inspected achieved Grade 1 in this field); accommodation; and hospitality and catering teaching. The College’s investment in Information Technology was praised by inspectors, with over five hundred workstations, a Collegewide communications network and good software range giving students and staff excellent access. The inspectors also noted the “specialist equipment of industrial standard” in hospitality and catering, hairdressing and beauty therapy, and in health and social care. Two years later the city of Plymouth was granted Unitary Authority status. Within the Authority boundaries there were two higher education institutions, the University of Plymouth and the College of St Mark & St John. Plymouth College of Art & Design, with which the college worked closely, is a specialist art college. There were 19 secondary schools, 14 comprehensives and five with selective entry. Apart from two comprehensives, all schools catered for the 16-18 age group. The College was therefore operating within an extremely competitive environment. Seven of the comprehensives were designated Community Colleges offering adult education. 23 In partnership, two of these providers and the College offered a coherent well-planned programme of adult education across Plymouth. In addition to the College’s provision at the two main sites, Kings Road and the Goschen Centre, there were three Neighbourhood Colleges at Martin’s Gate, North Road West and Camel’s Head, all specifically chosen to offer education in the community. By the end of 1999, the College could look back on a significant investment of approximately £10 million on accommodation and equipment over six years, resulting in outstanding facilities at the Goschen Centre, including the development of personal study areas, performing arts facilities and student recreation and social facilities. Continuing investment in Information Technology resulted in a ratio of computers to FTE students of better than 1:6. Major attention was given to improved access for the disabled. Further annual expenditure was planned to 2001, most significantly with the conversion of the former students’ refectory at Kings Road to a new sports hall, and a new extension of the main Kings Road block on the former car parking site, including new teaching areas and the Innovation Restaurant. In November 2000 an inspection was carried out by the Further Education Funding Council. It concluded that the proportion of good or outstanding teaching in the College was significantly better than the national average, with particularly high percentages of excellent teaching being observed in Business, Leisure & Tourism, and Basic Skills. Grade I’s were awarded for Resources and Support for Students, which were recognised as the areas of greatest importance to most customers. The excellent results and grades received by departments made a fitting valediction for the Principal, who retired at the beginning of December 2000 and was succeeded by David Percival, formerly Principal of Northampton College. David Percival, Principal 2000-2005 24 In October 2004 the College announced plans to fit two 6Kw wind turbines on the roof of the £3.2 Innovation Centre at the Kings Road site. This would involve the refurbishment of the main tower block, implementing green building principles and cladding two facades with photovoltaic cells that generate electricity from the sun. It was a major part of an initiative to produce examples of environmental good practice as well as research into the barriers preventing the adoption of green building methods. The electricity thus produced would feed into the building’s main supply, reducing dependence on carbon-based fuels. Funded through a £15,000 grant from EDF Energy’s Green Energy fund, a ClearSkies government grant and an EU project, BRITA in PuBs, the turbines were fitted in November 2005, thus finalising the original vision for the Centre which was designed to inspire others to include environmental design in their own buildings. It was believed that the College was the only one in the country at the time which had wind turbines fitted to a building. Electricity generated by the turbines went into the main supply of the building and was used for lighting and powering equipment including computers, pumps and catering appliances. It was anticipated that the amount of electricity thus produced in one year would be enough to supply ten average houses with all their power needs, apart from heating and hot water. In the summer of 2005 Mr Percival resigned to take up the post of Principal at Northbrook College, Sussex, as from September that year. Bill Grady, former Principal at North Trafford College, Manchester, was appointed interim Principal for the autumn term 2005 while a permanent successor was sought. Mrs Viv Gillespie, formerly VicePrincipal of Warwickshire College with responsibility for quality, curriculum and planning, joined at the start of the spring term 2006, thus becoming the College’s first female Principal. Viv Gillespie, Principal 2006 - 2011 25 During the year 2006/7 the public areas of the Hospitality training facilities were modernised, resulting in the creation of Cité Restaurant and later Cité Brasserie. Also in October 2006 the Hospitality department was awarded College of the Year by the Academy of Food & Wine Service. The College was singled out for providing young people in the industry with outstanding support and encouragement. Later that same a year a decision was taken to rebrand the College. Managers felt that the existing name failed to reflect the broad work of its role as a provider of everything from GCSEs and A-levels to Higher Education Foundation Degrees validated by the University of Plymouth. As from January 2007 it became City College, Plymouth. One year later, plans were unveiled to sell the college campus at Goschen. Major consideration had been given to moving completely to another site altogether. Millbay was regarded as providing unique opportunities for transformation as part of the ongoing regeneration of Plymouth City Centre under the ‘Vision for Plymouth’ plan launched in 2003, and this was initially seen as the favoured option, but no site large enough could be found in the regenerated area. A decision was then taken to move all facilities to Kings Road. The intention was that the latter would be demolished and rebuilt as part of a £70 million plan, subject to funding from the Learning and Skills Council. All the existing buildings, many of which were by then over thirty years old, were to be demolished and make way for state-of-the-art classrooms and workshops. While basically sound in a structural sense, they lacked adequate facilities for modern teaching, such as up-to-date wireless technology. Moreover, with hindsight the piecemeal development of the Kings Road centre over some thirty years had not made the best use of the site. 26 Just as economic constraints had delayed some stages of the College’s original construction and development during the 1970s, a similar scenario loomed again during the recession of 2007 onwards, and plans were put on hold while other sources of funding could be fully explored. Nevertheless, it was anticipated that on completion, the vastly improved new college would have more flexible teaching spaces, and cater for a different breed of learner from the students of thirty years earlier. After a review in May 2011, the College became the first in the UK outside of the pilot reviews to be awarded the Association of College’s Charter for Excellence in International Education and Training. It was commended particularly for the depth of its commitment to internationalisation at all levels, the strength of its partnerships locally, regionally and internationally and the quality of its international promotional materials. At the end of a six-year principalship in which the College achieved financial stability despite an extremely turbulent funding environment, as well as seeing its profile raised externally and a steady rise in success rates, Mrs Gillespie retired in December 2011. She was succeeded by Phil Davies, Lecturer in Business Management at Bedford University prior to his appointment to the college staff in 2002, and a Vice-Principal since 2008. At the time of his appointment the college was the largest provider of A-levels in Plymouth, with an overall rating among the top 10% in the country. There were 18,447 on the college roll, including 4,202 full-time students. ‘If you look at our total figure,’ he said, ‘you could say we educate the whole of Plymouth every fifteen years.’13 In October 2012 the college was the first in the country to be inspected using the new Ofsted common inspection framework. During a year in which the majority of colleges outside the area saw their grades fall the college, which had been adjudged ‘satisfactory’ after the previous inspection in 2008, was upgraded to ‘a good college with some outstanding features’. Among the key findings from the Ofsted report, it was noted Phil Davies, Principal 2011 - 27 that the proportion of learners achieving their qualifications had consistently improved since the last inspection and was now high; the provision for apprentices in engineering and learners in hospitality was outstanding; and all staff were strongly committed to continuing to raise the quality of teaching and learning and to improving further the experience of all learners.14 College Governors The Board of the Corporation, 15 including the Principal, draws its membership widely from local businesses and the broader community. A policy of a maximum of two 4-year terms ensures both continuity and planned turnover. Sub-committees include Audit, Finance, Personnel, Planning and Improvement, Search and Governance and Remuneration. Student Achievement Success rates among students aged 16-18 on levels 1, 2 and 3 long courses show an upward trend over the last three years. Success rates for both level 1 and 2 are above benchmark and within the upper quartile nationally. Retention rates among this age group have improved year on year over the last three years and are in line with the national benchmark. Achievement rates among this age group have also improved year on year over the last three years, most notably at Levels 1 and 2 where achievement has risen by 9% in both cases over the period. Amongst students aged 19+, success rates on levels 1, 2 and 3 long courses show an upward trend over the last three years and are all on or above the national benchmark. Success rates for levels 2 and 3 are within the upper quartile nationally. Retention rates among this age group have improved year on year over the last three years and are in line with the national benchmark. Achievement rates among this age group have also improved year on year over the last three years, where achievement has risen by 13%, 17%, and 14% for Levels 1, 2 and 3 respectively over the period. 28 Press Release (2006) Wind Turbines Plymouth College of Further Education installed two 6kw hour Wind Turbines on the roof of their Innovation Centre in October 2005. The installation was originally conceived as part of the development of the Innovation Centre in 2000. This new building amounts to 2500sqm and was designed to demonstrate the amount of good environmental practice which can be included when building to normal construction cost limits. This is scheme was very successful as an exemplar but there was insufficient funding for the Turbines at that time. The building includes such measures as high mass construction, passive ventilation, good day lighting, careful orientation, low energy lighting with automatic controls, solar thermal water heating, heat pump, rain water harvesting, waterless urinals and greener materials. Funding for the £70,000 Turbine installation was finally achieved from three sources. The Clear Skies programme provided the most significant contribution followed by BRITA in PuBs, a 6th framework fund of the European Community and EDF Energy. The installation was designed and the works managed by a company called Sustainable Energy Installations and the turbines were manufactured by Proven. To the credit of Plymouth City Council, obtaining planning consent and building regulation approval was relatively straightforward. With regard to planning the application it had to include a thorough environmental impact assessment. With regard to building regulations it was essential that the structural design calculation and drawings for the Innovation Centre were available. It is also worth noting that there was some limited local disquiet about the Turbine installation. This sprang mainly from the normal dislike of the idea of living in the locality of Wind Turbines. 29 The appearance of the installation on the Innovation Centre is both impressive and inspiring. The intention was their presence should add to the architecture of the building and this is being achieved in most people’s opinions. In terms of scale the Innovation Centre is four storey building. The Turbine blades have a diameter of 5.5m and they have a hub height above the flat roof surface of 9m. As expected noise is not a difficulty. The Turbines are direct driven so have no gearbox. This does mean the blade speed is fast producing an air swishing sound which in stronger wind conditions can sound more like helicopter blades as they feather to control maximum blade speed. These noises can only be heard when standing adjacent to the building and there is no sound transmission within the building itself. Vibration was another concern especially given the Innovation Centre is a steel framed structure. The structural design of the building required surprisingly little alteration when the decision was made to add the potential for Wind Turbines to the original scheme. It simply required adding stud columns to help provide the mounting points. The Turbine Towers bolt to a beam platform via dampers. The only vibration transmitted is a slight shudder on upper floors felt during stronger wind conditions. This did produce some occupier concern initially until they got used to the new conditions. An aspect that was underestimated is shadow flicker. The Turbines can project, particularly during sunny winter days, what amounts to a strobe light into rooms of neighbouring buildings. This effect is too strong to be blocked by normal office blinds. In practice, at the college, the turbines have been turned off for short periods on sunny days while the shadow moves across vulnerable rooms. The actual areas of vulnerability change as the seasons change. It is also possible that the moving cast shadow might disturb some people as well but this is much less significant than the strobe light effect. Fortunately the Turbines have been fitted with anti-vibration brakes that should operate if the Turbines destabilise due to damage. These are wired to allow remote operation for ease of turning the off units. 30 The output of the Turbines is wired through a pair of inverters for each unit into the main electrical system of the Innovation Centre. This was done via isolation and metering gear into an existing three phase board which had spare capacity. The overall annual output, given location and height, was estimated to be 33,800kw hours/per annum. Over the first five months of operation the output has been well below target suggesting an annual output of only 10,000kw hours/per annum. This might be partially explained by this past winter having fairly calm wind conditions. The output being so far short it is suspected that the inverter set points need adjustment and this is being investigated. Once we are confident on the expected output the college will decide whether to register the generation capacity for renewable obligation certificates. These can be sold to electricity suppliers to help them reach their renewable energy obligations. It has been pointed out that the registration system is highly bureaucratic and selling the certificates to the suppliers may also be less than straightforward. The overall experience of living with Wind Turbines is good. They generate much interest and provide visual impact to the college premises. Trying to resolve the poor output has been frustrating given both Proven and SEI are both located outside of the South West. Also the significant problem of shadow flicker took the college totally by surprise. Would the college still have such a Turbine installation given its current experiences? The answer to that is definitely yes but the knowledge may have meant certain things being done differently. 31 College Development - milestones College of Further Education authorised 1969 (November), came into existence 1970 (January) on designation of Plymouth Polytechnic; Plymouth College of Technology officially ceased to exist 1969 (December) Though there are no records of an official opening ceremony, during 1970 College was operating from 35 different annexes in Plymouth, major ones being Devonport Annexe, Durnford Street, Wyndham Street, King Street and Sherwell Church Hall, Prince Rock; some staff and accommodation shared by CFE and Polytechnic Other sites and operational dates: • Kings Road Phase I officially opened September 1974, enabling withdrawal from Mechanical and Electrical Engineering areas at Polytechnic, HM Dockyard Apprentice Training Centre, and facilities or annexes at Elliot Road, Charlotte Row, 83 North Road, North Hill, King Street Church, Sherwell Church, and Devonport Central Hall • Kings Road Phase I buildings came into use April 1975, enabling total withdrawal from Polytechnic premises and Martin's Gate School, and facilities or annexes at Armada Street, Rowe Street, Durnford Street, and 15 Portland Villas • North Road West opened 1980-2002 • Hotel & Catering Department, Kings Road opened 1983 • School of Maritime Studies merged with Plymouth Polytechnic September 1984 • Sutton annexe 1984-97 • Stoke Damerel, Albert Road annexes 1987-96 • Wyndham Street annexe closed 1987 • Mutton Cove annexe closed 1991 • Keyham annexe 1978-87 • Goschen Centre opened 1994 • Neighbourhood colleges various dates • Innovation Centre, Kings Road opened 2001 32 References 1. The Opening of the Technical College, Wednesday, 16 March 1955 [souvenir programme] 2. 'The attic students of a "homeless" college. ‘Western Evening Herald’, 21 February 1972 3. 'It's "all change" for further education.‘Western Evening Herald’, 6 September 1974 4. ibid 5. Principal's Report for the Academic Year 1974-75 6. Principal's Report for the Academic Year 1976-77 7. 'No more students" as cash curb hits college.‘Western Evening Herald’, 4 November 1976 8. Principal's Report for the Academic Year 1978-79 9. Principal's Report for the Academic Year 1980-81 10. Department of Education & Science: Report by HM Inspectors on Plymouth College of Further Education: Non-Advanced Further Education. DES, 1987 11. Wallace, Claire: Education, training and young people. In Plymouth: Maritime City In Transition (ed. Chalkley, Dunkerley, Gripaios). David & Charles, 1991 12. Principal's Report for the Academic Year 1986-87 13. “I’ve got the best job in Plymouth” (interview with Phil Davies). Western Evening Herald, 17 March 2012 14. Pulse, City College Plymouth Staff Magazine, Autumn Term 2012 33 Bibliography As per works cited in References, also: Plymouth College of Further Education, prospectuses and directories, 1970-71 onwards Principal's Reports for the Academic Year, 1970-71 onwards Kennerley, Alston (ed.): Notes on the History of PostSchool Education in the 'Three Towns'. Learning Resources Centre, Plymouth Polytechnic, 1976 Statement on the reorganisation of Further Education, 21 March 1991, DES circular Plymouth College of Further Education, Self-Assessment Report 98-99, updated May 2000 Plymouth College of Further Education Corporation Meeting Minutes, 29 November 2000 Miscellaneous local press cuttings, 1970 onwards Staff bulletins, 1996 onwards Plymouth Data website www.plymouthdata.info 34 4th edition 2013 Previous editions 1994, 2002, 2010 City College Plymouth Kings Road Devonport Plymouth PL1 5QG www.cityplym.ac.uk