Explaining correct voting in Swiss direct democracy

advertisement

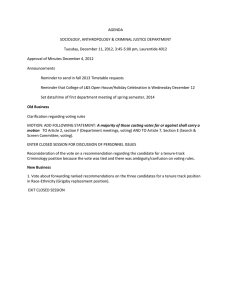

Swiss Political Science Association, Annual Meeting Geneva, January 2010 Explaining correct voting in Swiss direct democracy Alessandro Nai University of Geneva Abstract The quality of a political system, and especially a direct-democratic one, lies in the quality of the decisions citizens take. As some authors argue, this can be measured through the overall presence of "correct voting", namely the fact that even uninformed citizens can mimic the choice of political experts (Lupia 1994; Lau and Redlawsk 1997 and 2006). A growing body of researches tries to identify and explain the presence of correct voting (Holbrook and McClurg 2006; Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008; McClurg and Sokhey 2008). These researches have essentially concentrated on electoral issues rather than on the decisions taken by citizens on ballot propositions (Hobolt 2007 being the only exception we know of). The aim of the present paper is consequently to propose a multilevel model capable of explaining the presence of correct voting in direct-democratic choices. Built on Swiss data on federal ballots (VOX data, 1999-2005), our model will investigate the simultaneous effects on correct voting of individual characteristics (mainly political sophistication), cognitive strategies activated by citizens (the use of different heuristics), and contextual factors (intensity of the campaign, priming, justification of arguments, negative campaigning, and complexity of the project voted). As our results show, a higher quality of the decision is produced by explanatory factors from different levels. Our paper thus opens up new venues for studying political behaviour by showing that analyses of correct voting should not be limited to electoral issues, and by providing empirical analyses able to grasp the theoretical complexity behind the emergence of more accurate decisions. Introduction1 Citizens often lack of political sophistication. They are not motivated, they do not possess the basic knowledge needed to take a competent decision, and often make no serious effort to compensate the lack of information they suffer. In brief, they are ill equipped for the political tasks (Delli Carpini and Keeter 1993 and 1996; Zaller 1992; Alvarez & Brehm 2002). This being, citizens may know how to drive even without knowing how an engine is made (Bowler and Donovan 1998). In order to overcome their difficulties, some citizens rely on 1 A previous version of this paper has been prepared for the annual meetings of the American Political Science Association (APSA, September 2009) and the World Association For Public Opinion Research (WAPOR, September 2009). 1 cognitive shortcuts, which provide them "dependable answers even to complex problems" (Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock 1991: 19). The widespread literature on the use of such heuristics has however often little to say on what a "dependable answer" is. Some authors argue that the quality of a decision may be measured through the capacity to mimic the behaviour of political experts (Lupia 1994; Lau and Redlawsk 1997; 2006; Holbrook and McClurg 2006; Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008; McClurg and Sokhey 2008; Christin, Hug and Sciarini 2002). Almost all literature on "correct voting" is however as of today focussed on electoral issues, rather than on direct democratic decisions (Hobolt 2007 being a notable exception). We aim to compensate this lack. We will investigate the presence of correct voting in Swiss direct democracy, and try to determine under which conditions this is more likely to happen. Switzerland is an excellent laboratory for the study of direct democracy. First, in a mere quantitative way, a huge part of the popular votes held around the world take place there (Butler and Ranney 1994; Trechsel and Sciarini 1998). This creates a huge amount of data that can quite easily be used for our purposes. Second, Swiss direct democracy allow citizens to express themselves on a wide range of different topics, from international relations to fiscal policies (Trechsel and Sciarini 1998). Third, which is the most important, direct democracy in Switzerland has a very important and defining role for the whole political system. As Kobach states, "Switzerland is the only nation in the world where political life truly revolves around the referendum" (Kobach 1994: 98). The institutions of direct democracy – popular initiative, optional and mandatory referenda – introduce a healthy uncertainty into the political process (Ossipow 1994), and they bound the control of the elites on the political processes in a twofold way (Trechsel and Sciarini 1998: 101 ff.): first, they create a new arena for direct intervention by the electorate in some major decisions; second, they force the elites to moderate hey propositions, since they can quite easily be attacked from the bottom (following the famed Neidhart's hypothesis; Neidhart 1970). In such a context, where the place of ordinary citizens is at the core of the political system, it is clear that an analysis of the quality of their decision demands some special attention. Our paper constitutes a premiere with Swiss data. No previous research exists for the presence of correct voting for Swiss citizens, even if their cognitive behaviour has been studied quite extensively (e.g. Marquis and Gilland Lutz 2004; Kriesi 2005; Marquis 2006; Nai and Lloren 2009). 2 Following what has been done for American electors elsewhere (Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008), we will look simultaneously at individual and contextual determinants of correct voting. At the individual level we will give special attention to the level of sophistication and to the activation of cognitive heuristics (and especially partisanship). Citizens however do not form their opinion on their own, and even less without being subjected to a series of external influences. Political campaigns are an important source of information during opinion formation, and their influence is today highly studied (e.g. Holbrook 1996; Bowler and Donovan 1998; Schmitt-Beck and Farrel 2002; De Vreese and Semetko 2004; Lau and Redlawsk 2006). For this, we will investigate whether the quantitative presence of campaigns and the quality of their content can help us to understand the presence of correct voting. We will first discuss some theoretical implications on how to efficiently measure correct voting; we shall propose an alternative way to determine who the "more informed" citizens are, those for which the behaviour is mirrored. Instead of simply looking at the quantity of factual knowledge detained, we will consider the actual decisional capacity of citizens (Kuklinski and Quirk 2001). We will assume that a citizen who forms its opinion through a systematic treatment of information (Eagly and Chaiken 1993) can be seen as a particularly capable one. After a short methodological chapter, we will investigate under which conditions this is more likely to happen. Correct voting? The main point, before looking at its determinants, is of course how to measure the "correctness" of the decision taken by citizens. One way to determine whether or not a decision is good is to impose external criteria. With this approach, the researcher decides that, in a given situation, some citizens should vote in a specific way in order to cast a "good vote". Such a solution is easy to execute, and has the advantage of being relatively clear. However, on the other hand, it faces a strong risk of subjectivity and bias. In fact, "in labeling judgments as 'good', 'sound', or 'competent', the difficulty is to find criteria independent of the decisionmaking process. […] Unfortunately, as in any other public-opinion research, standards of quality turn on values, debatable facts, or both. In general, we can discriminate between better and worse political opinions only by positing normative criteria, which are in all cases open to criticism" (Kuklinski and Quirk 2000: 157). Therefore, a definition on what a correct decision is should be based "on the values and beliefs of the individual voter, not on any particular ideology that presumes the values and preferences which ought to be held by members of 3 different social classes, for instance, and not on any larger social goods or universal values" (Lau and Redlawsk 1997: 586). Every decision, if taken freely, is legitimate (Downs 1957); in a democratic system that allows free and independent reasoning, each choice is as good as all the others. However, as some authors state, decisions may still be seen as having a higher or lower quality: a choice could be qualified as "incorrect" if it would be different when taken under better conditions. In order to take the decision that is more likely to correspond to our political profile, we need to know the more we can on the subject at stake. If we desire to elect the candidate who better defends the issues we care for, we have to know his political profile and those of its adversaries. If we are asked to support or reject a ballot proposition, we should at least know what are the consequences of an approval or refusal for us, or the country. However, as we know, incomplete information is a quite common situation when facing a decision. If one could demonstrate that a choice taken under incomplete information would not be the same with full information on the subject, then that first choice may be seen as incorrect. On the other side, if there is consistency between the choice made and the optimal one, the citizen could be seen as having cast a correct vote. Therefore, "correct voting refers to the likelihood that citizens, under conditions of incomplete information, nonetheless vote for the candidate or party they would have voted for had they had full information about those same candidates and/or parties" (Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008: 396). Such citizens are able to mimic the behaviour of the more informed ones, and cast a vote that is similar as the one they would have taken if they were more informed. Following such "as-if" premise, a growing body of researches tries nowadays to evaluate the quality of the decision taken by citizens, as well as its determinants (Lau and Redlawsk 1997 and 2006; Holbrook and McClurg 2006; Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008; McClurg and Sokhey 2008). This has however not be done systematically, as of today, for direct-democratic situations. What determines correct voting? Some expectations Political behaviour has historically been studied by looking primarily at its individual determinants. Early researches on vote and participation showed that individuals are strongly influenced by their political predispositions, as well as their level of sophistication. More recently, literature on political behaviour has begun to understand that contextual determinants also play a key role (e.g. Kuklinski et al. 2001; Kriesi 2005; Keele and Wolak 2008). Citizens do not exist in a conceptual void, and it seems nowadays simplistic to think 4 that what is around them does not influence their decision. Following what has been recently done by Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk (2008), we believe therefore that correct voting is strongly affected by individual and contextual determinants simultaneously. At the individual level, we expect political sophistication to play a key role on a correct decision. Sophistication has often been shown as a strong determinant of political behaviour, in what it enhances a higher attention and more generally a more efficient opinion formation (Zaller 1992; Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996; Alvarez and Brehm 2002). Furthermore, political sophistication triggers a higher cognitive engagement through the activation of a systematic behaviour (Kam 2005; Kriesi 2005; Nai et Lloren 2009). For this, we believe that among citizens who did not take their decision in an optimal way (i.e citizens that did not activate any systematic reasoning), the more sophisticated ones are the more likely to imitate the decision of those with a higher cognitive engagement; when this condition is missing, citizens cannot make a correct choice. Results found in Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk (2008) confirm this expectation for American electors. We have therefore: H1: correct voting is enhanced by higher political sophistication. Furthermore, we could expect that those citizens who at least try to compensate their lack of cognitive engagement (by activating cognitive shortcuts) may know a higher level of correct voting. Following Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock (1991: 19) "insofar as [heuristics] can be brought into play, people can be knowledgeable in their reasoning about political choices without necessarily possessing a large body of knowledge about politics". The motivation to activate an heuristic reasoning could be seen as an incentive to mimic the behavior of the more sophisticated citizens (which signals a correct vote). Following what has been found recently for the American voters (Lau and Redlawsk 2001; 2006; Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008), this seems to be especially true for the more sophisticated ones. We may expect therefore that "the advantages of heuristics use to disproportionately advantage experts – those least in need of cognitive shortcuts" (Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008: 398). Following some major works in the field, we shall concentrate on referential shortcuts. These shortcuts allow forming an opinion through cues from the political elite (Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock 1991; Bowler and Donovan 1998; Lupia and McCubbins 1998; Lau and Redlawsk 2001; Kam 2005). Those shortcuts presuppose that citizens are at least capable of 5 adapting their behaviour as a function of the cues received during opinion formation. Therefore: H2: correct voting is enhanced when cognitive shortcuts are activated, and especially for those citizens with higher sophistication. At the contextual level, we shall focus on the political campaign before the ballot. As others before us, we believe that political campaigns strongly affect the opinion formation processes of individuals. More intense campaigns activate the interest of citizens on the topics, motivate their participation, and enhance their attention (Ansolabehere and Iyengar 1995; Bowler and Donovan 1998; Norris 2002; Valentino et al. 2001; De Vreese and Semetko 2004; Lau and Redlawsk 2006; Wolak 2009). Therefore, "to the extent that campaigning translates into the greater availability of (or ease of obtaining) information […, one can expect] campaign intensity to be positively related to correct voting" (Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008: 398). In addition of their intensity, four other dimensions of political campaigns will be retained in our analyses: the priming power of the arguments in the campaign, their variety and justification level, and the overall level of negative campaigning. These four additional dimensions measure the quality of the campaign, whereas the intensity measures its quantitative presence. First, the priming of a campaign measures the way the arguments in the debate are retained by citizens while taking their decision (Jacobs and Shapiro 1994; Kinder 1998; Iyengar and Simon 1993; Druckman 2004). A strong priming signals that campaign arguments strongly influence the motivations that are behind citizens' choices (Iyengar and Simon 1993: 368). We believe that a campaign with a higher priming is more likely to enhance correct voting, to the extent that stronger arguments will push even unsophisticated citizens to take the better decision they can. The relative presence of different arguments will simply measure their variety; we anticipate that a higher variety signals a higher quality of the debate, which may enhance the presence of correct voting. Thirdly, a debate may be more or less rich; independently of the absolute presence of information (intensity) or the persuasive power of the arguments (priming), a campaign may be built on arguments that are more or less robust (Steiner et al. 2004). We believe that arguments with a higher justification level, i.e. arguments whose contribution to the author's position is straightforward, may open the gate for a better behaviour. 6 Fourth, an aggressive debate has been shown to decrease turnout (demobilizing effect; see Ansolabehere and Iyengar 1995; Ansolabehere et al. 1994), to amplify political cynicism (Valentino et al. 2001; De Vreese and Semetko 2002), and to globally increase the gap between population and the political elite (Lau et al. 1999). We anticipate a very similar effect on correct voting: we believe that a debate particularly rich in attacks (i.e. a debate with a high level of negative campaigning) may undermine the efforts necessary for non-systematic voters to mimic the behavior of the more engaged ones. Priming, justification, variety and negative campaign measure the quality of the information provided to citizens during opinion formation. They are anticipated to increase the likelihood of correct voting. We will also see whether differences in the complexity of the task may affect correct voting. Swiss citizens are asked to form an opinion on a wide range of projects, which vary highly in terms of the complexity of their content (Caramani 1993; Wälti 1993; Kriesi 2005). As Lau et al. point out, "objectively easier tasks generally result in more highquality decisions than more difficult tasks" (2008: 397). We also believe that more complex projects will produce higher difficulties for citizens, which will decrease the likelihood that those latter vote correctly. We have therefore: H3: correct voting is enhanced by intense campaigns, high priming, high variety of arguments and high justification. It diminishes with higher negative campaigning and higher complexity of the topic. How to measure correct voting Some decisions can be qualified as correct even if taken under incomplete information. Some citizens are able to mimic the behaviour of the more informed ones, and cast a vote that is similar to the one they would have taken under better conditions. By definition, they cast a "correct vote". In order to measure the presence of correct voting, we have beforehand to discriminate the citizens with regards to the quantity/quality of information they possess. The proxy group (well-informed proxy group; Kuklinski and Quirk 2001: 296), mirrored by the less sophisticated citizens, should be built on two premises: "First, the members should have values and interests similar to those of the focal group – ideally, the identical values and interests. Second, they should make, in some serious sense, well-informed and capable decisions on the issue at hand. The more informed and capable the proxy group is, the more rigorous is the resulting criterion" (Kuklinski and Quirk 2001: 302). 7 We shall develop later the way we measure the similarity of interests and values among the proxy and the focal group. First, we wish to discuss the way to determine who the more informed and/or capable citizens are. Usually, this is quite simply done by looking at the quantity of information about an issue (or a candidate) a person is able to put forward. The higher the factual knowledge on the issue (candidate, political program, ballot proposition, etc.), the higher the likelihood that the person is part of the proxy group. Following Kuklinski and Quirk (2001), this raises some major concerns. First, building the proxy group in a coherent way presupposes a strict definition of what a good knowledge on the issue is. Even admitting this as an easy task, the problem lies in that the explicit link between factual knowledge and attention on the issue (which produces a citizen that is really informed) is not straightforward. In other terms, having some knowledge on a subject does not allow to decide, at the end, if that person is really informed or not. For this, basing the construction of the proxy group on the level of factual knowledge on the issue, as for example done by Lupia (1994), is at best perilous (Kuklinsk and Quirk 2001: 303). Secondly, selecting the reference group solely on the level of information is also theoretically problematic. By looking only at the level of factual information detained, other individual characteristics that may play a key role on opinion formation may be underestimated. More informed citizens "might differ from others in a variety of relevant ways. Some of the differences – in income, education, and political ideology, for example – are likely to be measured and thus can be taken into account statistically at the individual level. But other difference, for example, in cultural values or cognitive styles, usually will not be measured. If these unmeasured differences have important effects on preferences, they would tend to confound comparisons between the two groups" (Kuklinski and Quirk 2001: 302). Following the definition given by Kuklinski and Quirk, the reference group should be composed of sophisticated citizens, able to take decisions in an informed and capable way. The literature on correct voting seems mainly focussed on the first dimension. Previous researches of Lupia (1994), Lau and Redlawsk (1997, 2006), and other scholars on correct voting build the reference group by looking, in a way or another, at the level of factual knowledge. In order to avoid the two problems put forward before, we propose here to shift the focus toward the second dimension of sophistication in Kuklinski and Quirk's definition: the level of decisional ability. In order to measure whether or not a citizen is able to take a decision in a capable way, we will look at his level of cognitive engagement during the 8 opinion formation. This will be done by establish which cognitive strategy he activated during such process. The use of different cognitive strategies when facing a decision has extensively been shown in empirical research on neurosciences (Epstein 1994; Stanovich and West 2000; Evans 2003). Following Stanovich and West (2000), individuals take decisions following System1 or System 2 processes. System 1 is characterized as automatic, unconscious, and undemanding of computational capacities. Inversely, System 2 signals a controlled and demanding processing of information (Stanovich and West 2000: 658-659). Some major models developed in cognitive psychology support the existence of two different mental paths. Researches by Shelley Chaiken and colleagues put forward a dual model of opinion formation, the Heuristic-Systematic Model (HSM), which shapes each decision as a fluctuation between two cognitive strategies: heuristic and systematic process of decisiontaking (Chaiken 1980; Eagly and Chaiken 1993). Heuristics are judgemental shortcuts that help citizens to take their decision without requiring a large amount of sophistication or information. By contrast, citizens can also choose to activate a systematic reasoning, which can be seen as a "controlled processing of information" (Stanovich and West 2000: 658-659). More precisely, a systematic processing is an analytic orientation to information processing in which individuals access and scrutinize a great amount of information on its relevance to their judgemental task (Eagly and Chaiken 1993: 326). Systematic citizens engage in demanding mental efforts, through voluntary and robust decrypting of information and arguments where "all things are considered" (Barker and Hansen 2005). In short, systematic treatment represents the highest level of cognitive engagement. We assume here that a citizen who forms its opinion by activating such strategy can be seen as a particularly capable one. For this, we will build our reference group not by looking at the level of factual knowledge hold by citizens, but instead by simply ascertain those who have built their opinion through systematic reasoning. We shall therefore consider that correct voting exists when a citizen who has not activated a systematic reasoning takes the very same decision than those who had a higher cognitive engagement during opinion formation. Of course, both groups (focus and proxy) have to share the same values and political preferences (Kuklinski and Quirk 2001: 302). When dealing with electoral situations, this is 9 quite easily done by looking the positioning of the citizen toward a series of issues (e.g. immigration, energy policies, affirmative action, and so on), and at the positioning of the candidates on those very same issues (see Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008). In our case this is simply not possible, since we deal with ballot propositions and not electoral issues. The better solution we have to make sure that both the focus and the proxy group share the same values is to look at the ideological position of the respondents (simply done through the selfpositioning on the left-right scale). Therefore, correct voting exists when a citizen who has not activated a systematic reasoning takes the same decision than those who had a higher cognitive engagement during opinion formation, by holding constant the ideological position of citizens in both groups. Our data show that for Swiss ballots (at the federal level, between 1999 and 2005) about 21% of non-systematic citizens voted correctly2, which is below the levels found elsewhere for American electors (Lau and Redlawsk 1997 and 2006; Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk 2008; McClurg and Sokhey 2008). We observe furthermore huge differences among different projects; the level of correct voting varies between a minimum of 0% for several projects and a maximum of 68.7%. After some methodological considerations, we will try to determine what may induce its presence. Data and methods Empirical analyses are based on data coming from surveys made after federal ballots between 1999 and 2005 (VOX data; N = 77'7663). In Switzerland, often several projects are submitted conjointly in a ballot; our period covers 23 federal ballots, in which 75 different projects were submitted. After each ballot, a random three-stage sample of about 1000 individuals was constructed. All individual factors are directly or indirectly measured through the VOX data; contextual factors are drawn from a content analysis of the political ads fond in the press before the vote. Two dimensions of political sophistication are analyzed here: the level of factual knowledge on the issues related to the ballot and the level of political motivation. Factual knowledge is measured through two ballot-related questions, one asking to retrieve the exact title of the 2 3 Calculated among non-systematic citizens having participated in the ballot, and only when at least 60% of the proxy group voted consensually (N=28'920). Analyses done only for those citizens who declared having participated. 10 project submitted, and the other to briefly explain its content. To each exact answer one point is attributed; this produces a 0-2 variable where 2 points signal the highest knowledge. Political motivation is deducted from a question asking whether citizens are in general interested in politics; those who declare having a strong interest in politics are the more motivated ones. The use of referential strategies is deducted indirectly, since no direct measure of the cognitive behaviour exists in VOX data. A vote identical to the instruction provided by the closest party signals a partisan heuristic, while a vote identical to the government's instruction signals a trust heuristic when trust in government is high. McClurg ans Sokhey (2008) compute the use of partisan heuristic in a similar way. At the contextual level, the five dimensions of the political campaign before the vote intensity, priming, justification, variety and negative campaigning - are measured through a content analysis of political ads found in the press before the vote. Political ads provide voting instructions, and are financed by institutional or independent political actors. For the whole 1999-2005 period, we scrutinized six major journals of the Swiss deliberative space4. Every political ad published in the month before the vote was retained; we collected about 7200 different ads. We found a sufficiently high number of ads5 for about only the half of the projects (34 on the overall 756); where only a few ads were found, indicators were not considered as robust. Intensity of the campaign is measured through the overall size of the ads found in the press for a specific object multiplied by their number. The higher the score, the higher the intensity. A similar procedure has been done elsewhere (Kriesi, Sciarini and Marquis 2000; Kriesi 2005: 40 sgg.; Marquis 2006: 403 sgg.). A simplified ordinal variable (very low, low, high, very high intensity) is built on the quartiles of the original continuous variable. Priming of the arguments is retraced by confronting the main arguments7 found in the ads for a specific object (and vote direction) with the aggregate spontaneous vote motivations given 4 5 6 7 Tribune de Genève, Le Temps (French), Neue-Zürcher Zeitung, Tages-Anzeiger (German), Regione, Giornale del Popolo (Italian). Those journals cover a high amount of the information provided by journals, and cover the main ideological orientations of the Swiss press. At least 4 ads during the 4 weeks preceding the vote in at least 2 linguistic regions (for both directions of the campaign) were considered as sufficient. Among those 34 projects, one had to be also excluded since no measure of correct voting was possible (missing data on key variables). Analyses for the contextual level will be carried on 33 cases. Following Petty and Priester (1994; in Marquis 2006: 466), and argument is an information that says something on the validity of the decision. In other terms, an argument is an explicit reason that supports the vote instruction provided in the ad. Several arguments may be contained in every single ad. 11 by citizens in VOX surveys. If a high correlation exists between the arguments and the spontaneous motivations, the priming has been high. In order to facilitate the comparison, the classification of arguments found in the press is made backwards, starting from the classification of the spontaneous vote motivations in the VOX data (Marquis 2006: 467; Kriesi, Sciarini and Marquis 2000: 12). Correlation is measured by looking at the absolute number of principal arguments both distributions have in common. Variety of arguments looks at the absolute number of different arguments developed in each campaign. The level of justification of the arguments is measured following what proposed by Steiner et al. (2004) for parliamentary debates. Their main idea is that "the tighter the connection between premises and conclusions the more coherent the justification is" (Steiner et al. 2004: 21). They recognize four levels of justification (2004 : 57 ff. and 171-173): absent (no justification provided by the author of the ad), inferior (there is a justification, but the inference between the reason and the vote recommendation is not explicit), qualified (explicit link between justification and recommendation; full inference), and sophisticated (two or more qualified justifications present in the ad). During content analysis, we attributed to each ad a value on a 0-3 scale (3 signals the presence of sophisticated justification, 0 the absence of any justification, and so on); for each campaign, the value of justification is simply the mean value on this scale for each ad; the higher, the stronger the justification level of the campaign. Negative campaigning is measured by attributing one point to each ad that contains one or more explicit attacks toward the political adversaries. The value for each campaign is simply the percentage of ads containing those attacks. Complexity of the project is computed by looking, for each project, at the part of citizens declaring having had difficulties during the opinion formation. The higher that part, the more complex the project had to be (Kriesi 2005). Coan et al. (2008) compute their measure of complexity in a quite similar way. Such procedure measures the perceived complexity of the project; this allows us to avoid any bias in establishing it through external estimations8. Correct voting exists by our definition when a citizen who has not activated a systematic reasoning takes the same decision than those who had a higher cognitive engagement (both groups sharing the same values). In order to see whether or not a citizen has activated a systematic reasoning, we need to ascertain 1) if he was able to treat a high amount of 8 For example by asking at some political experts to class the projects from the easiest to the more complex, as done elsewhere (Kriesi 2003). 12 information, and 2) if he was able to assimilate the arguments present in the information treated. In our data, a question asks the respondents about the intensity of the information search during opinion formation. Second, in our data respondents were asked to position themselves on a battery of arguments related to the political campaign before the ballot. We believe that those citizens who have a strong positioning toward those arguments have been more able to comprehend and assimilate them, which is an indicator of systematic behaviour. By combining those two dimensions, we considered that a systematic strategy was activated when the citizen had consulted a higher amount of information and was able to strongly position himself toward the main arguments in the campaign9. In the integrated dataset covering all Swiss ballots between 1999 and 2005, 24.3% of citizens used systematic reasoning. We created 3 categories of ideological positioning (left, right, centre) starting from the selfpositioning of respondents on a 10 points left-right scale. For each category, the choice of the systematic voters (decision of the majority of 60% or more among them10) is the reference in order to compute the existence of correct voting for the non-systematic citizens. Due to missing data on the original variables on campaign arguments used to compute the presence of systematic reasoning, 6 projects were excluded from our analyses. Results Our aim is to show that individual and contextual determinants work together to shape correct voting. For this, a hierarchical generalized linear model (HGLM) has been run11. Table 1 presents the results for the model with both fixed and random effects. We see first that sophistication enhances the quality of the vote, but only through the level of motivation. As expected, a stronger political motivation increases the likelihood that the nonsystematic citizen indeed votes correctly. In order to mimic the behaviour of those that formed 9 10 11 In our data, respondents declared having consulted an average of 5.4 information sources during opinion formation. High information search exists when 6 or more different sources have been consulted. In order to measure the strength of positioning toward arguments, a series of factor analyses have been performed on the original questions (which ask respondents to declare if they are in favor, neutral, or against each argument). The extracted factor represents the principal conflict dimension of the campaign (Kriesi 2005; Nai and Lloren 2009). Those who have a strong positioning toward such factor are considered to have strongly integrated the arguments. More details on the measure of systematic behavior are available upon request. When no clear majority was found, correct voting was impossible to compute. We work with a binary dependent variable (presence or not of correct voting); a logit transformation is therefore used. Our models are run with HLM 6.06 (Raudenbush et al. 2004) through Restricted Maximum Likelihood (RML); all variables entered in the models as grand centered. 13 their opinion though systematic reasoning, citizens have to dispose of some key cognitive tools that may trigger their reflection. Being motivated in everything that is political seems to give them what they need. This confirms partially our first hypothesis. Unexpectedly, disposing of a higher knowledge on the project voted does not affect the quality of the decision; the likelihood of correct voting is very similar among citizens with different levels of knowledge. We note that McClurg and Sokhey (2008) also find no statistically significant effect of knowledge on correct voting. Like in Lau et al. (2008) and McClurg and Sokhey (2008), our results provide great support for the heuristic hypothesis. Even in direct-democratic situation, where the link between choice and party affiliation is more indirect that in elections, partisanship is a very strong predictor for correct voting. Our results clearly show that the likelihood that non-systematic citizens vote correctly is strongly increased for those that activated a partisan heuristic. Knowing the position of the preferred party clearly helps all citizens to form their opinion (Bowler and Donovan 1998; Lupia 1994; Lupia and McCubbins 1998; Kam 2005); our results show that a huge help is also provided by partisanship to those that desire to mimic a systematic behaviour they could not afford. We see a counterintuitive result for trust (only significant in the random effects model). An activation of trust heuristic diminishes the use of correct voting. Interpretation of such result is not straightforward, but may be related to the government position on different direct democratic instruments; a major difference exists between popular initiatives and referenda (Kriesi 2005: 20 ff.). The first intervene at the very beginning of the decision-making process; an initiative launches the debate and forces elites and government to redefine their main concerns (agenda-setting function). By contrast, referenda intervene at the very end of the process, once the legislative body has adopted a proposition. Government naturally assumes opposite roles depending on the nature of the instrument: a defensive role for referenda, an offensive role for initiatives12. We may therefore imagine that citizens modify their cognitive behaviour - the use of trust heuristic - depending on the government's role. An alternative model also controlling for the effect of the instrument type partially confirms this intuition (results not shown). The difference between initiatives and referenda does not affect directly the quality of the decision (no significant direct effect on correct voting), but has an interesting cross-level effect with the use of trust heuristic; the use of trust heuristic strongly 12 This is evidently not a written rule. It may happen, for example, that a popular initiative is defended not only by those who launched it but also by the government itself. This is however very rare. 14 increases the likelihood of correct voting during votes on referenda (i.e. when government has a defensive role), and strongly decreases that likelihood for popular initiatives, where an offensive role is played by the government. This does not help to understand why the use of trust heuristic has a general negative effect on correct voting; it may however shed some light on how citizens react to government's positions with a specific cognitive behavior. All other determinants in this alternative model have very similar effects to those in Table 1. ---------Table 1 about here ---------We also expected the use of heuristics to advantage more sophisticated citizens, but our results do not allow to confirm this hypothesis; the interactive effects between the use of heuristics and the two dimensions of sophistication are hardly significant. The only interesting effect exists between knowledge and the use of trust heuristic: the combined presence of these two determinants significantly increases the likelihood of correct voting. This effect is however only present in the model with fixed effects, and completely disappears when slopes are allowed to randomly vary across level-2 units (random effects). Our results show that the context in which citizens form their opinion highly influence the quality of their decision. This appears both generally13 and specifically for the various contextual dimensions. First, and surprisingly enough, the intensity of the campaign does not enhance the use of correct vote, quite the contrary. Disposing of a higher quantity of information on which form their opinion, non-systematic citizens seem to mimic way less the systematic ones. Too much information may kill the information. In analysing the effect of network disagreement on correct voting, McClurg and Sokhey find that being subjected to multiple and contrasting points of view (which signals a high network disagreement) diminishes the quality of the vote. They imagine that being exposed to multiple points of view may enhance the ambivalence of citizens, which makes their final decision more difficult (McClurg and Sokhey 2008: 15). In 13 We found a quite high interclass correlation (which can be interpreted as the correlation between two level-1 observations randomly chosen among a randomly chosen level-2 observation). This means that individual units (citizens) are strongly nested into contextual observations (the ballots). 15 our case, we could therefore imagine that being exposed to a high quantity of information increases the difficulties faced when mimic the behaviour of the systematic citizens. A similar conclusion can be drawn for the level of justification of arguments; facing a campaign composed by more robust arguments (i.e. arguments with a better justification), citizens are less inclined to vote correctly. More robust arguments are, by definition, more complex; qualified justifications demand higher attention. We may therefore imagine that "easier" arguments are better tools for those citizens who desire to mimic a behaviour they could not afford. This being, and as expected, disposing of a higher variety of arguments enhance a better behaviour. Even if the absolute quantity of information (intensity) works against the quality of the vote, as seen above, a greater quantity of arguments does the opposite. When information is abundant, only a few arguments are presented and those last are too complicated to assimilate, citizens face a more complex task. As pointed out by Kuklinski et al. (2001: 412), "a small amount of highly pertinent information will often enhance citizens competence far more than a mountain of peripherally relevant facts and arguments. Rather than the volume, then, it is the diagnostic value of information that influences how well citizens are able to cope with policy choices". This seems pertinent for the Swiss case, where correct voting is better enhanced by the diversification of the information (variety of arguments) rather than by its quantitative presence. The stronger result in Table 1 concerns the effect of negative campaigning. Odds for negative campaigning are noteworthy pointed toward the fact that a more offensive campaign produces a decision with higher quality. This invalidates our expectation that a debate filled with negativism produces a demobilizing effect (Ansolabehere and Iyengar 1995; Ansolabehere et al. 1994) also with regards to correct voting. Quite the contrary, a higher level of attacks seems to provoke some sort of stimulation, similar to the one found on turnout by Finkel and Geer (1998). Citizens may therefore answer an excessive negativism with an increasing of their interest in the topic, which may lower the difficulties in mimic the behaviour of the systematic ones. Negative elements may certainly discourage part of the electorate, but may also facilitate the access to information for others (Crigler et al. 2006; Geer 2006). Contrarily to what expected, finally, complexity and priming do not seem to influence correct voting. In a nutshell, context strongly enhances correct voting but in a fairly more complex way than anticipated. A better decision is more likely achieved when citizens face not-too-abundant 16 information, composed by various but not-too-complex arguments. Furthermore, negativism probably increases the attention to the debate, and thus facilitates the access to the information provided by the campaign. Conclusion The quality of a political system, and especially of a direct-democratic one, lies in the quality of the decisions citizens take. As cleverly pointed out by Lau and Redlawsk (2006: 74), "if we are going to make judgements about the 'democratic' nature of different forms of government, we should do so at least initially on the basis of the quality of correctness of the political decisions that citizens make […] rather than on the basis of the ways in which those decisions are reached". As some authors argue, the quality of such decisions can be measured through the overall presence of "correct voting", namely the fact that even uninformed citizens can mimic the choice of political experts (Lupia 1994; Lau and Redlawsk 1997; 2006). Correct voting for electoral situations has drawn some serious attention lately. However, only scarce literature exists on its presence also during direct-democratic events. Given the central role played by citizens (and their decisions) in such contexts, a systematic analysis on the quality of their decision was needed. In this paper, we measured the presence of a correct voting as the imitation of those citizens that formed their opinion through systematic reasoning (Eagly and Chaiken 1993). Our aim was to demonstrate that correct voting is enhanced not only by some major individual assets, but also by the dynamics at the contextual level. Through a series of hierarchical models, we proved that correct. Our results show, first, a direct effect of sophistication on correct voting; those non-systematic individuals that were particularly motivated had a higher chance to cast a correct vote. Again, this shows the fundamental role of sophistication as impulsion for a better political behaviour. Our results also prove that partisanship has a key role on correct voting. Knowing the position of the preferred party clearly helps all citizens to form their opinion; our results show that a huge help is also provided by partisanship to those that desire to mimic a systematic behaviour they could not afford, which provides strong support for the heuristic hypothesis. At the contextual level, we showed that too much information works against a better decision. Probably by decreasing the risk of ambivalence (which leads to higher difficulties), a less intense campaign enhances correct voting. Easier but variegate arguments also push citizens 17 toward a better decision; when information is abundant but only a few arguments are presented, citizens face a more complex task. Finally, Swiss citizens seem to react positively to more offensive campaigns, i.e. campaigns whose interventions are characterised by a higher level of attacks or offences. Instead of demobilise the voters as often proposed in the literature (Ansolabehere and Iyengar 1995; Ansolabehere et al. 1994), negative campaigning seems to stimulate citizens toward a better behaviour. The effects shown for the contextual variables on correct voting are not only empirically interesting. They provide consistent support to the idea that the quality of political processes can be enhanced top-down. By working on the content of political interventions – e.g. by providing more focussed information, composed by various but easier arguments – political actors can directly push the citizens toward a better behaviour. Citizens should however not adopt a wait-and-see approach, and justify their defection solely on the deficiencies of the informational environment. Independently of the quantity and quality of the information, individual determinants still play a key role on the quality of their behaviour. Finally, showing that correct decisions can be reached also in unfavourable situations answers directly to some major criticisms that are drawn against direct democracy (see Butler and Ranney 1994: 17 ff.). Accordingly, "if most people, most of the time, vote correctly, then we should not be too concerned if those vote decisions are reached on the basis of something less than full information" (Lau and Redlawsk 2006: 74). Especially in a political system where the role of citizens is important (and growing), the presence of correct decisions reassures about the capacities of the electorate. 18 References ALVAREZ, Michael and BREHM, John (2002). Hard choices, easy answers. Values, information, and American public opinion. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ANSOLABEHERE, Stephen and IYENGAR, Shanto (1995). Going negative. How political advertisements shrink and polarize the electorate. New York: The Free Press. ANSOLABEHERE, Stephen, IYENGAR, Shanto, SIMON, Adam and VALENTINO, Nicholas (1994). "Does attack advertising demobilize the electorate?" The American Political Science Review 88(4): 829-838. BARKER, David and HANSEN, Susan (2005). "All things considered: Systematic cognitive processing and electoral decision-making." The Journal of Politics 67(2): 319-344. BOWLER, Shaun and DONOVAN, Todd (1998). Demanding choices: Opinion, voting, and direct democracy. Ann harbour: University of Michigan Press. BUTLER, David and RANNEY, Austin (Eds.) (1994). Referendums around the world. The growing use of direct democracy. Houndmills: Macmillan. CARAMANI, Daniele (1993). "La perception de l'impact des votations fédérales", in: KRIESI, Hanspeter (Dir.). Citoyenneté et démocratie directe. Compétence, participation et décision des citoyens et citoyennes suisses. Zurich: Seismo, pp. 77-98. CHAIKEN, Shelly (1980). "Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of sources versus messages cues in persuasion". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39(5): 752-766. CHRISTIN, Thomas, HUG, Simon and SCIARINI, Pascal (2002). "Interests and information in referendum voting: An analysis of Swiss voters." European Journal of Political Research 41(6): 759776. COAN, Travis, MEROLLA, Jennifer, STEPHENSON, Laura and ZECHMEISTER, Elizabeth (2008). "It's not easy being Green: Minor party labels as heuristic aids." Political Psychology 29(3): 389-405. CRIGLER, Ann, JUST, Marion and BELT, Todd (2006). "The three faces of negative campaigning: the democratic implications of attack ads, cynical news, and fear-arousing messages"; in: REDLAWSK, David (Ed.). Feeling politics. Emotion in political information processing. New York: Palgrave, pp. 135-163. De VREESE, Claes and SEMETKO, Holli (2004). "News matters: Influences on the vote in the Danish 2000 Euro referendum campaign". European Journal of Political Research 43(5): 699-722. DELLI CARPINI, Michael and KEETER, Scott (1996). What American knows about politics and why it matters. New Haven: Yale University Press. DOWNS, Anthony (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper Collins. DRUCKMAN, James (2004). "Priming the vote: Campaign effects in a U.S. Senate election." Political Psychology 25(4): 577-594. EAGLY, Alice and CHAIKEN, Shelly (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. 19 EPSTEIN, S. (1994). Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious." American Psychologist 49(8):709-724. EVANS, Jonathan (2003). "In two minds: Dual-process accounts of reasoning." Trends in Cognitive Sciences 7(10): 454-459. FINKEL, Steven and GEER, John (1998). "A spot check: casting doubt on the demobilizing effect of attack advertising." American Journal of Political Science 42(2): 573-595. GEER, John (2006). In defense of negativity: Attacks ads in presidential campaigns. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. HOBOLT, Sara (2007). "Taking cues on Europe? Voter competence and party endorsements in referendums on European integration." European Journal of Political Research 46(2):151-182. HOLBROOK, Thomas (1996). Do campaigns matter? Thousand Oaks: Sage. HOLBROOK, Thomas and McCLURG, Scott (2006). "The presidential campaign and correct voting in 2000." Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwestern Political Science Association, Chicago, April 19-23. IYENGAR, Shanto and SIMON, Adam (1993). "News coverage of the Gulf crisis and public opinion. A study of agenda-setting, priming and framing". Communication Research 20(3): 365-383. JACOBS, Lawrence and SHAPIRO, Robert (1994). "Issues, candidate image, and priming: The use of private polls in Kennedy's 1960 Presidential campaign." The American Political Science Review 88(3): 527-540. KAM, Cindy (2005). "Who toes the party line? Cues, values, and individual differences." Political Behavior 27(2): 163-182. KEELE, Luke and WOLAK, Jennifer (2006). "Value conflict and volatility in party identification." British Journal of Political Science 36(4): 671-690. KINDER, Donald (1998). "Communication and opinion." Annual Review of Political Science 1:167197. KOBACH, Kris (1994). "Switzerland"; in: BUTLER, David and RANNEY, Austin (Eds.). Referendums around the world. The growing use of direct democracy. Houndmills: Macmillan, pp. 98-153. KRIESI, Hanspeter (2005). Direct democratic choice. The Swiss experience. Oxford: Lexington Books. KRIESI, Hanspeter (Dir.) (1993). Citoyenneté et démocratie directe. Compétence, participation et décision des citoyens et citoyennes suisses. Zurich: Seismo. KRIESI, Hanspeter, SCIARINI, Pascal and MARQUIS, Lionel (2000). "Démocratie directe et politique extérieure: étude de la formation des attitudes en votation populaire". Rapport de synthèse (NFP42) dans le cadre du PNR "Politique extérieure de la Suisse". Berne. KUKLINKSI, James and QUIRK, Paul (2000). "Reconsidering the rational public: Cognition, heuristics, and mass opinion"; in: LUPIA, Arthur, McCUBBINS, Mathew and POPKIN, Samuel (Eds.). Elements of reason. Cognition, choice and the bounds of rationality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 153-182. 20 KUKLINSKI, James and QUIRK, Paul (2001). "Conceptual foundations of citizen competence." Political Behavior 23(3): 285-310. KUKLINSKI, James, QUIRK, Paul, JERIT, Jennifer and RICH, Robert (2001). "The political environment and citizen competence". American Journal of Political Science 45(2): 410-424. LAU, Richard and REDLAWSK, David (1997). "Voting correctly". American Political Science Review 91(3): 858-598. LAU, Richard and REDLAWSK, David (2001). "Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making." American Journal of Political Science 45(4): 951-971. LAU, Richard and REDLAWSK, David (2006). How voters decide. Information processing during election campaigns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. LAU, Richard, ANDERSEN, David and REDLAWSK, David (2008). "An exploration of correct voting in recent US presidential elections." American Journal of Political Science 52(2): 395-411. LAU, Richard, SIEGELMAN, Lee, HELDMAN, Caroline and BABBIT, Paul (1999). "The effects of negative advertisement: A meta-analytic assessment". The American Political Science Review 93(4): 851-875. LUPIA, Arthur (1994). "Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: Information and voting behaviour in California insurance reform elections." The American Political Science Review 88(1): 63-76. LUPIA, Arthur and McCUBBINS, Mathew (1998). The democratic dilemma. Can citizens learn what they need to know? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. MARQUIS, Lionel (2006). La formation de l'opinion publique en démocratie directe. Les référendums sur la politique extérieure suisse, 1981-1995. Zurich: Seismo. MARQUIS, Lionel and GILLAND LUTZ, Karin (2004). "Thinking about and voting on Swiss foreign policy: Does affective and cognitive involvement play a role?" Sussex European Institute, EPERN Working Paper (18). McCLURG, Scott and SOKHEY, Anand (2008). "Social networks and correct voting." Southern Illinois University Carbondale Working Paper. NAI, Alessandro et LLOREN, Anouk (2009). "Intérêts spécifiques et formation de l'opinion politique des suissesses (1999-2005)." Swiss Political Science Review 15(1): 99-132. NEIDHART, Leonhard (1970). Plebiszit und pluralitäre Demokratie. Eine Analyse der Funktionen des schweizerischen Gesetzreferendums. Bern: Francke. NORRIS, Pippa (2002). "Do campaign communications matter for civic engagement? American elections from Eisenhower to George W. Bush"; in: FARRELL, David and SCHMITT-BECK, Rüdiger (Eds.). Do political campaign matter? Campaign effects in elections and referendums. New York: Routledge, pp. 127-144. OSSIPOW, William (1994). "Le système politique Suisse ou l'art de la compensation"; in: PAPADOPOULOS, Yannis (Dir.). Elites et people en Suisse. Analyse des votations fédérales: 19701987. Lausanne: Réalités Sociales, pp. 9.56. 21 RAUDENBUSH, Stephen, BYRK, Anthony, CHEONG, Yuk Fai, CONGDON, Richard and Du TOIT, Mathilda (2004). HLM 6: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modelling. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software International (SSI). SCHMITT-BECK, Rüdiger and FARRELL, David (2002). "Studying political campaigns and their effects"; in: FARRELL, David and SCHMITT-BECK, Rüdiger (Eds.). Do political campaign matter? Campaign effects in elections and referendums. New York: Routledge, pp. 1-21. SNIDERMAN, Paul, BRODY, Richard and TETLOCK, Philip (1991). Reasoning and choice. Explorations in political psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. SNIJDERS, Tom and BOSKER, Roel (1999). Multilevel analysis. An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modelling. London: Sage. STANOVICH, Keith and WEST, Richard (2000). "Individual difference in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate?" Behavioral and Brain Sciences 23:645-726. STEINER, Jürg, BÄCHTIGER, André, SPÖRNDLI, Markus and STEENBERGEN, Marco (2004). Deliberative politics in action. Analysing parliamentary discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Theories of Institutional Design. TRECHSLER, Alexander and SCIARINI, Pascal (1998). "Direct democracy in Switzerland: Do elites matter?" European Journal of Political Research 33(1): 99-124. VALENTINO, Nicholas, BECKMANN, Matthew and BUHR, Thomas (2001). "A spiral of cynicism for some: The contingent effects of campaign news frames on participation and confidence in Government". Political Communication 18(4):347-367. WÄLTI, Sonia (1993) "La connaissance de l'enjeu", in: KRIESI, Hanspeter (Dir.). Citoyenneté et démocratie directe. Compétence, participation et décision des citoyens et citoyennes suisses. Zurich: Seismo, pp. 25-50. WOLAK, Jennifer (2009). "The consequences of concurrent campaigns for citizens knowledge of congressional candidates." Political Behavior 31(2): 211-229. ZALLER, John (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 22 Tables Table 1: Hierarchical generalized linear models for correct voting Multilevel determinants Model with fixed effects odds ratio (Se) Model with random effects odds ratio (Se) Intercept .05 (.4)*** .03 (.4)*** Level-1 variables Political knowledge Political motivation Partisan heuristic Trust heuristic Political knowledge * Partisan heuristic Political knowledge * Trust heuristic Political motivation * Partisan heuristic Political motivation * Trust heuristic 1.09 (.1) 1.63 (.1)*** 10.62 (.4)*** .67 (.6) .84 (.1) † 1.99 (.2)** .83 (.1) † .77 (.2) 1.01 (.2) 1.65 (.1)*** 12.65 (.5)*** .20 (.7)* 1.02 (.1) 1.06 (.1) .73 (.2) † .75 (.2) Level-2 variables Justification Intensity Priming Variety Negative campaigning Complexity .08 (1.6) .35 (.6) † 1.06 (.3) 1.09 (.0)* 898.04 (3.0)* 1.00 (.0) .10 (1.0)* .28 (.4)** .80 (.2) 1.08 (.0)*** 127.8 (2.2)* .96 (.0) † Variance components Chi-sq Chi-sq Intercept Political knowledge Political motivation Partisan heuristic Trust heuristic Political knowledge * Partisan heuristic Political knowledge * Trust heuristic Political motivation * Partisan heuristic Political motivation * Trust heuristic . . . . . . . . . 1050.6*** 61.7*** 59.0*** 44.7*** 26.9 39.6 † 5.2 58.0*** 34.9 Interclass correlation (intercept-only model) a N (level-1) N (level-2) ρ =.55 19'924 34 Note: Dependent variable is the presence of a correct vote (binary variable). Models have been run with HLM 6.06, through Restricted Maximum Likelihood (RML) estimations. Effects controlled by age, sex and education (individual level), and year of the vote (contextual level). a Interclass correlation for multilevel logistic models is calculated through the following approximation: ρ = (σ2u0) / (σ2u0 + π2/3). The variance of level-2 residuals (σ2u0) is divided by the total variance (σ2u0 plus the variance of the logistic distribution for level-1 residuals π2/3=3.29). See Snijders and Bosker (1999: 224) for more details. *p<0.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001, †p<.1 23