LAB #9

advertisement

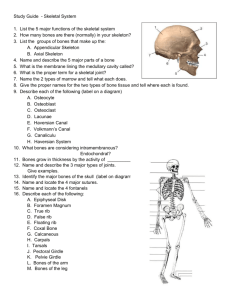

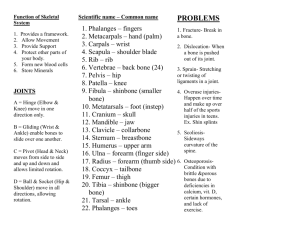

Biology 241 – Lab LAB #9 (9th/21 Lab Sessions for Fall Quarter, 2008) TOPICS TO BE COVERED: »Demonstration of boney landmarks of the 1 Hyoid Bone »Demonstration of boney landmarks of the 25 bones of the rib cage (Sternum and 24 Ribs) »Demonstration of boney landmarks of the 4 bones of the Pectoral (aka Shoulder) Girdle »Demonstration of boney landmarks of the 60 bones of the Upper Extremities DESIRED OUTCOMES: After completing the activities described for this lab session, students should: »Be able to locate and identify a hyoid bone and describe its salient features. »Be able to identify the bones of the thoracic cage and selected surface markings »Be able to identify all bones of the appendicular division of the skeleton, including distinguishing Right from Left »Be able to identify the bones of the pectoral (shoulder) girdle and their principle boney landmarks »Be able to identify the bones of the upper extremity and their principle boney landmarks MATERIALS NEEDED: »Articulated Skeletons »Pipe Cleaners (for pointers) »Disarticulated Skeletons »Photographic Atlas, Ch. 5/6/7 »Tortora textbook Activity #1: Boney Landmarks of the Hyoid Bone The hyoid bone is not attached to the axial skeleton but is included with the axial skeleton because of its midline location and proximity to the mandible and vertebral column. This bone is U-shaped and has the distinction of not articulating with any other bones of the body. Instead, it “floats” in the superior aspect of the neck just below the mandible being secured by ligaments and muscles of the tongue and neck both above it and below it. (Its chief anchoring is to the styloid processes of the temporal bones by ligamentous attachment.) It is located in the anterior neck region between the mandible and the larynx. This is the bone that is crushed during strangulation; therefore, it is examined very carefully at autopsy when strangulation is suspected. The hyoid bone itself consists of a horizontal body and paired projections called the lesser horns (aka lesser cornu) and the greater horns (aka greater cornu). These provide the sites of attachment for extrinsic tongue muscles and for muscles of the neck and pharynx. Activity #2: Boney Landmarks of the Bones of the Rib Cage The boney structure that encircles the chest is called the rib cage (aka thoracic cage) and is composed of 25 bones: 1 sternum and 24 ribs. (Of course, the 12 thoracic vertebra, with which the ribs articulate posteriorly are in this same region; however, the vertebra have already been studied, and are included with the bones of the vertebral column – studied in the previous lab.) Also: be sure to note that males and females HAVE THE SAME NUMBER OF RIBS (24)….because even if one of Adam’s ribs were “removed” in order to fashion Eve, then, that rib’s periosteum was left intact….and the rib grew back!! So, NO: men do NOT have one fewer ribs than women! Biology 241 – LAB #9 – continued Page Two The sternum is a narrow flat bone that is composed of three fused bones: the manubrium, the body (aka gladiolus), and the xiphoid process. The manubrium (“handle”) is the superior-most segment of the sternum and has a distinct concave superior marking called the suprasternal notch (aka jugular notch). (You can feel your own suprasternal notch by placing the middle finger of your hand directly in the anterior midline at the base of your neck.) Also on the lateral aspect of the manubrium, note the costal facet for rib pair #1, and the demifacet for rib pair #2. The body (aka gladiolus) of the sternum is the middle, longest segment of the sternum whose lateral borders are “indented” six times: once with a demifacet for rib pair #2 and five times with costal facets for rib pairs #3 - #7. Also, the sternal angle – the margin of fusion between the manubrium and the body is a most important clinical landmark – as it is the site of attachment of the second rib, inferior to which is the second intercostal space. (This is one of the locations where auscultation of certain heart valves can best be heard.) The xiphoid (“pointed”, “sword-like”) process is the inferior-most segment of the sternum and has no costal facets associated with it. Usually the xiphoid process is like a small sword; but sometimes it is bifid; and sometimes it has a through-and-through hole (foramen) in it. There are 12 pairs of ribs in both males and females. The fist 7 pairs are called true ribs (aka vertebrosternal ribs) because their costal cartilages have a direct attachment to the sternum: Ribs #1 with the manubrium; Ribs #2 at the sternal angle (junction of the manubrium with the body); Ribs #3 - #7 with the body. The last five pairs of ribs (#8 - #12) are called false ribs (aka vertebrochondral ribs), because their costal cartilages do not have any direct attachment to the sternum – but rather to the costal cartilage of the rib above each of them. Furthermore, rib pairs #11 and #12 have no attachment to either the sternum nor to the costal cartilage above; therefore, these are additionally called floating ribs (aka vertebral ribs). (They, of course, do NOT “float” as they are attached posteriorly to vertebra T11 and T12 respectively.) The space between two successive ribs is called an intercostal space; in each case, the space is named for the rib BELOW which it occurs. In other words: the 1st intercostal space is BELOW rib #1 (aka between rib #1 and rib #2); the 2nd intercostals space is BELOW rib #2 (aka between rib #2 and rib #3); etc. These can be “read” well on chest X-rays – any views: anterior, posterior, or lateral. Ribs are flat bones whose main parts are the head, neck, tubercle, and body. The head projects from the posterior part of the rib and its facet articulates either with a facet on the body of a single vertebra or into the demifacets of the bodies of two adjacent thoracic vertebrae to form a vertebrocostal joint. The neck is the constricted part lateral to the head. The tubercle is a small knoblike projection on the posterior surface where the neck joins the body. There are two parts to the tubercle: the nonarticular part of the tubercle attaches to the transverse process of a vertebra by a ligament; the articular part of the tubercle articulates with the facet of a transverse process of the inferior of the two vertebrae. These articulations also form vertebrocostal joints. The body (aka shaft) is the main part of the rib. A short distance beyond the tubercle, an abrupt change in the curvature of the body occurs. This point is called the costal angle. Also, on the inner, inferior surface of each rib, there is a costal groove that was formed (as the rib ossified) around blood vessels and a thoracic spinal nerve to protect them. To tell a Right rib from a Left rib: Place the rib on the table-top and: 1. Always orient the rib so that its superior aspect is up which means the costal groove will be down. 2. Make sure that the vertebral end (head of the rib) is closest to you; thus the sternal end will be away from you. 3. If the head and sternal ends are lined up with the “midline”as above, then the body of the rib will be curved outward to the same side to which the rib belongs; and you can “try it on for fit”. In other words, if the convexity is toward the right, it is a right rib; if its convexity is toward the left, it is a left rib. Biology 241 – LAB #9 – continued Page Three Activity #3: Boney Landmarks of the Bones of the Pectoral (aka Shoulder) Girdle The Appendicular Skeleton (appendere = Latin: to hang upon) has larger bones than does the Axial Skeleton and bears more weight. Specifically, the upper extremities “hang” from the pectoral girdles; and the lower extremities “hang” from the pelvic girdle. There are two pectoral girdles, and each attaches an upper limb to the Axial Skeleton. Each pectoral girdle is composed of a scapula and a clavicle. Each clavicle has a sternal end, which is the tall, blunt, medial end; and an acromial end, which is the broader, flat, roughened, lateral end. (Of course, the sternal end articulates with the manubrium of the sternum to form the sternoclavicular joint; and the acromial end articulates with the acromion of the scapula to form the acromioclavicular joint.) The superior surface of the clavicle is quite smooth; whereas the inferior surface is rougher and there are two landmarks on this inferior surface: the conoid tubercle, on the lateral end of the bone, and the impression for the costoclavicular ligament on the inferomedial end. (Respectively, these serve at sites of attachment for the conoid ligament which attaches the clavicle and scapula; the costoclavicular ligament which attaches the clavicle and first rib.) To tell Right from Left on the clavicle, the only additional bit of anatomical information needed is to discern anterior from posterior. One does this by understanding that the clavicle has a laterally oriented “sigmoid (S-shaped) curve” to it whose convex curvature is medial and whose concave curvature is lateral. Now, having differentiated all three orientations: superior from inferior; anterior from posterior; and medial from lateral – just “try the bone on” and you’ll CONFIRM whether you are looking at a R or L clavicle! As previously seen, the acromial end of the clavicle articulates with the acromion (acromial process) of the scapula laterally, forming the pectoral girdle. The sternal end of the clavicle articulates with the manubrium of the sternum medially, attaching the pectoral girdle to the axial skeleton. The scapula, however, does not articulate directly with the axial skeleton, but is attached to it with muscles. Each scapula (aka shoulder blade) is a large, triangular, irregular bone situated in the superior part of the posterior thorax between the levels of the second and seventh ribs. You will be shown each of the landmarks of the scapula, including: the body (with its two angles: the superior angle and inferior angle); its three borders: medial (vertebral) border, lateral (axillary) border, and superior border; its prominent spine whose lateral end projects as a flattened, expanded process called the acromion (this is the highpoint of the shoulder); the coracoid process; the glenoid cavity; and the three large fossae: supraspinous fossa and infraspinous fossa both on the posterior surface of the scapula and the subscapular fossa on the anterior surface of the scapula. Activity #4: Boney Landmarks of the Bones of the Upper Extremities Each upper limb consists of the humerus (1), ulna (1), radius (1), carpals (8), metacarpals (5), and phalanges (14). Of the 30 bones in each upper extremity, one is in the arm (the humerus); two are in the forearm (the ulna and radius), eight are in the wrist (8 carpals), and the remaining nineteen are in the hand (5 metacarpals and 14 phalanges). You will be shown each of the landmarks that are required learning for these bones, and then, for reinforcement, there will be a cooperative learning exercise. The procedure for this exercise will be as follows: 1. Each Lab Bench has four students who will be considered “a group” If your Lab Bench has fewer, two Lab Benches may work together. 2. Each group will be given either a humerus, an ulna, a radius, or an articulated hand (including carpals.) Biology 241 – LAB #9 – continued Page Four 3. Each student in each group will spend approximately 3 – 5 minutes learning the assigned structures on his/her own, using the Photographic Atlas or the textbook rendition of that bone, if he/she isn’t the one actually holding the bone itself. 4. Now, one member of the group will act as “Spokesperson” and will tell whether the bone is a R or a L (rationale MUST be given for the decision), and then will identify all of the assigned boney landmarks on the bone. (Each student in each group is expected to listen, watch, and follow along correcting the Spokesperson if there is an error.) 5. Each bone with its assigned structures is now rotated clockwise, so that each group has a new set of structures to learn and to practice. Again, silently for the first 3 – 5 minutes, each member of the group studies the landmarks on his/her own, using the Atlas, if not the actual bone itself. 6. Now, a different member of the group will volunteer to be Spokesperson to first tell whether the bone is a R or a L (including rationale) and then to identify all of the assigned boney landmarks on the bone. 7. The process is repeated until each student has been the Spokesperson, ideally for each bone. By the end of this exercise, students will have learned the assigned landmarks for each bone in today’s lab session. Humerus: This is the largest long bone in the upper extremity; it gives support, shape, and leverage to the upper limb. Here are the important boney landmarks to identify on the humerus: *head – rounded, proximal end *anatomical neck – constriction immediately distal to the head *greater tubercle – lateral projection distal to the anatomical neck *lesser tubercle – smaller, anterior projection distal to the anatomical neck *surgical neck – constriction distal to the tubercles *deltoid tuberosity – raised area on the lateral side *trochlea – spool-shaped medial condyle on the distal end *capitulum – rounded, knoblike condyle lateral to trochlea *medial epicondyle – rough projection above the trochlea *lateral epicondyle – rough projection above capitulum; smaller than the medial epicondyle *coronoid fossa – shallow depression on the anterior aspect of the distal end (receives the coronoid process of the ulna when the forearm is flexed at the elbow) *olecranon fossa – largest depression on the posterior aspect of the distal end (receives the olecranon process of the ulna when the forearm is extended at the elbow) Ulna: This is the medially located bone of the forearm. Its salient boney landmarks include the: *olecranon – large, dense, boney projection on the posterior side of the proximal end (This is the landmark for which the entire posterior elbow region of the body is named. Also, when you lean on your elbows, these are the boney eminences that bear your weight. ) *coronoid process – smaller, curved, liplike projection on the anterior side of the proximal end; distal to the olecranon *trochlear notch – deep, curved area between the olecranon and the coronoid process *styloid process – slender, pointed projection on the distal end *radial notch – depression on the proximal end where the head of the radius articulates with the ulna *head – the rounded, distal end of the ulna that articulates with the radius at the ulnar notch Radius: This is the laterally located bone of the forearm. Its salient boney landmarks include the: *head – flat, disc-shaped proximal end that articulates with the capitulum of the humerus and the radial notch of the ulna *ulnar notch – rounded articular surface at the distal end of the radius that receives the head of the ulna *styloid process – where the diaphysis widens distally to form a slender, pointed projection on the lateral side. (This boney landmark can be felt proximal to the thumb on the posterolateral aspect of the wrist .) Biology 241 – LAB #9 – continued Page Five Carpus (aka Wrist): The carpus is composed of eight short bones, the carpal bones, which are lined up in two rows. They form a proximal row and a distal row of bones. Two of the carpal bones articulate with the radius, but there is no articulation of the carpal bones with the ulna. The names of the eight bones are (and the order in which they are arranged in the two rows, starting with the proximal row, thumb side; then coming back to the thumb side to start the distal row): Proximal row, starting at the thumb side: Scaphoid, Lunate, Triquetrum, Pisiform Distal row, coming back to the thumb side again to start: Trapezium, Trapezoid, Capitate, Hamate (Remember, the mnemonic device for naming these bones is the following saying: Some Lovers Try Positions …… That They Can’t Handle!! Metacarpus (Palm of the Hand): The metacarpus is composed of five metacarpal bones that make up the palm of the hand. They are numbered using Roman Numerals I – V starting with the metacarpal of the thumb on the lateral side and proceeding medially to end with the metacarpal of the little finger (“pinky) on the medial side. The metacarpals articulate with the carpals proximally and with the phalanges distally. Phalanges (Fingers of the Hand): The phalanges (singular is phalanx) make up the fingers or digits. The fingers are also numbered I – V starting from the thumb (pollex) to the little finger. The thumb consists of two phalanges, proximal phalanx and distal phalanx. Digits II through V each have proximal, middle, and distal phalanges (phalanx = closely knit row).