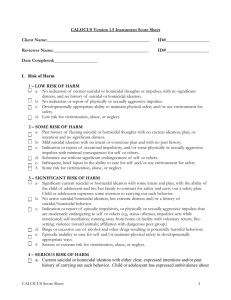

AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF

advertisement