CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES AND ADULT AGGRESSION Sarah Castagnola

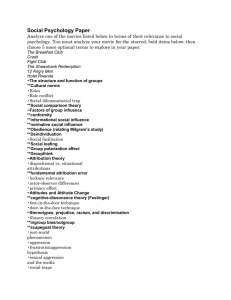

advertisement