Psychology 2700 – Animal Behaviour Review – Final Exam

advertisement

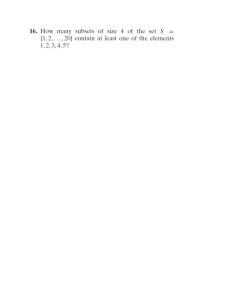

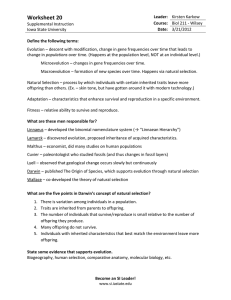

Psychology 2700 – Animal Behaviour Review – Final Exam Investing in offspring – Parent offspring conflict and sibling rivalry – Ch. 8 Successful reproduction does not end with mating, as reproductive success ultimately hinges on offspring survival, which can entail considerable investment in some species. Here, selection should favor parents who optimize the balance between the costs and benefits of their investments in offspring. These lectures examined various strategies parents use to accomplish this, for example, by manipulating the sex ratio of offspring born under certain conditions, or by biasing their investment in some more than other offspring (e.g., first- or last-born infants). However, because offspring will not necessarily ‘agree with’ these parental strategies, there can arise conflict between parents and offspring, or among offspring, over the amount and timing of investments. For example, there comes a time for parents when further investment in current offspring does not improve that offspring’s chances of survival but does limit the parents’ ability to invest in future offspring. At this point, it pays parents to curtail investment in offspring in anticipation of investment in future offspring. At the same time, however, offspring are selected to maximize the investment they receive from parents (up to a point), and so selection should favor infants that solicit additional investment from parents. This simultaneous selective pressure on parents and offspring results in conflict over the allocation of resources. This is another arms race that emphasizes the way in which selection acts simultaneously, not independently, on the various parties to an interaction. Graphs from Parental Care lectures: Primate sex-ratio biasing: aggression, injury and sex-ratio in rhesus macaques A G G R E S SI O N I N J U R Y Infanticide and child abuse in humans: i. INF Genetic ANT -biased ICID abuse E Parent-offspring conflict graph: We then introduced the concepts of inclusive fitness and kin selection to better illustrate exactly why conflict occurs between parents and offspring and between siblings, and to understand why these individuals are also often tolerant or even cooperative. Ultimately, we need to appreciate how genetic relatedness can play a role in structuring a wide range of social relationships. Family tree examples from lecture: Examples using formula: r = X(0.5)L (where X=# common ancestors; L=# generational links) a. Parent-offspring: r = 1(0.5)1 = 0.5 B A b. Nephew/niece: r = 2(0.5)3 = 0.25 B A c. Grandparent – grandchild: r = 1(0.5)2 = 0.25 B A d. Cousins: r = 2(0.5)4 = 0.125 B A Interacting with Others – Cooperation – Ch. 9 Many mammalian species live in groups that contain both related and unrelated individuals. Therefore, individuals are faced with the additional challenge of deciding who they should help, in addition to family members, and when. This lecture section will focus on the different forms of cooperation that can be evolutionarily stable among unrelated individuals including, mutualism and altruism (reciprocity). Mutualism involves multiple individuals acting together towards a common shared goal that no one individual could obtain on its own. In this situation, there are immediate benefits for all individuals involved. Altruism, however, involves asymmetric costs and benefits for the different individuals. One individual pays the costs of cooperating and receives no benefit, while the other receives benefits and pays no cost. In order for such altruistic (self-sacrificing) behaviour to evolve, the altruistic acts must be reciprocated and the social conditions under which this is likely to occur are rather stringent: the opportunity for repeated encounters must be infinite (or at least very high); individuals must recognize one another; and they must be able to punish cheaters (or at least withhold future altruistic support). Interacting with Others – Communication – Ch. 12 Communication is used in practically every aspect of social living. Therefore, another problem faced by individuals is how to communicate effectively with group members, potential mates and even potential predators. It is important to understand that communication is not necessarily a cooperative behaviour; it is a dyadic interaction between senders and receivers. Therefore, we can expect different selection interests for those producing signals and those receiving signals. Signals benefit senders by manipulating and affecting a receiver’s behaviour, while receivers may benefit if they obtain reliable information that allows them to respond adaptively. Therefore, we will also explore the potential honesty or reliability of signals. In order for signals to persist and be adaptive they should generally be reliable, otherwise receivers would ignore signals. This simultaneous selection on senders and receivers emphasizes again that although each have very different interests, selection does not act on each independently. We will explore the reliability of signals and the differential selection interests of senders and receivers through signaling examples in each of the major behavioural domains we have considered thus far: foraging, mating and antipredator behaviour. Graphs from communication lectures: Waggle dance direction and distance graphs