Atoms, Molecules, and Ions

advertisement

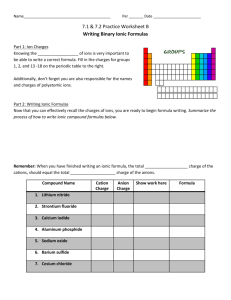

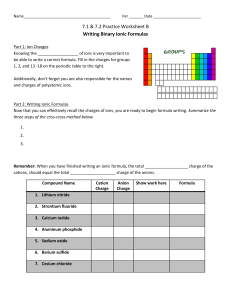

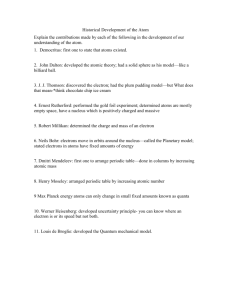

Atoms, Molecules, and Ions Chemistry Timeline #1 B.C. 400 B.C. Demokritos and Leucippos use the term "atomos” 2000 years of Alchemy 1500's Georg Bauer: systematic metallurgy Paracelsus: medicinal application of minerals 1600's Robert Boyle:The Skeptical Chemist. Quantitative experimentation, identification of elements 1700s' Georg Stahl: Phlogiston Theory Joseph Priestly: Discovery of oxygen Antoine Lavoisier: The role of oxygen in combustion, law of conservation of mass, first modern chemistry textbook Chemistry Timeline #2 1800's Joseph Proust: The law of definite proportion (composition) John Dalton: The Atomic Theory, The law of multiple proportions Joseph Gay-Lussac: Combining volumes of gases, existence of diatomic molecules Amadeo Avogadro: Molar volumes of gases Jons Jakob Berzelius: Relative atomic masses, modern symbols for the elements Dmitri Mendeleyev: The periodic table J.J. Thomson: discovery of the electron Henri Becquerel: Discovery of radioactivity 1900's Robert Millikan: Charge and mass of the electron Ernest Rutherford: Existence of the nucleus, and its relative size Meitner & Fermi: Sustained nuclear fission Ernest Lawrence: The cyclotron and trans-uranium elements Dalton’s Atomic Theory (1808) All matter is composed of extremely small particles called atoms Atoms of a given element are identical in size, mass, and other properties; atoms of different John Dalton elements differ in size, mass, and other properties Atoms cannot be subdivided, created, or destroyed Atoms of different elements combine in simple whole-number ratios to form chemical compounds In chemical reactions, atoms are combined, separated, or rearranged Modern Atomic Theory Several changes have been made to Dalton’s theory. Dalton said: Atoms of a given element are identical in size, mass, and other properties; atoms of different elements differ in size, mass, and other properties Modern theory states: Atoms of an element have a characteristic average mass which is unique to that element. Modern Atomic Theory #2 Dalton said: Atoms cannot be subdivided, created, or destroyed Modern theory states: Atoms cannot be subdivided, created, or destroyed in ordinary chemical reactions. However, these changes CAN occur in nuclear reactions! Discovery of the Electron In 1897, J.J. Thomson used a cathode ray tube to deduce the presence of a negatively charged particle. Cathode ray tubes pass electricity through a gas that is contained at a very low pressure. Thomson’s Atomic Model Thomson believed that the electrons were like plums embedded in a positively charged “pudding,” thus it was called the “plum pudding” model. Mass of the Electron 1909 – Robert Millikan determines the mass of the electron. The oil drop apparatus Mass of the electron is 9.109 x 10-31 kg Conclusions from the Study of the Electron Cathode rays have identical properties regardless of the element used to produce them. All elements must contain identically charged electrons. Atoms are neutral, so there must be positive particles in the atom to balance the negative charge of the electrons Electrons have so little mass that atoms must contain other particles that account for most of the mass Rutherford’s Gold Foil Experiment Alpha particles are helium nuclei Particles were fired at a thin sheet of gold foil Particle hits on the detecting screen (film) are recorded Try it Yourself! In the following pictures, there is a target hidden by a cloud. To figure out the shape of the target, we shot some beams into the cloud and recorded where the beams came out. Can you figure out the shape of the target? The Answers Target #1 Target #2 Rutherford’s Findings Most of the particles passed right through A few particles were deflected VERY FEW were greatly deflected “Like howitzer shells bouncing off of tissue paper!” Conclusions: The nucleus is small The nucleus is dense The nucleus is positively charged Atomic Particles Particle Charge Electron -1 9.109 x 10-31 Electron cloud Proton +1 1.673 x 10-27 Nucleus 0 1.675 x 10-27 Nucleus Neutron Mass (kg) Location The Atomic Scale Most of the mass of the atom is in the nucleus (protons and neutrons) Electrons are found outside of the nucleus (the electron cloud) Most of the volume of the atom is empty space “q” is a particle called a “quark” About Quarks… Protons and neutrons are NOT fundamental particles. Protons are made of two “up” quarks and one “down” quark. Neutrons are made of one “up” quark and two “down” quarks. Quarks are held together by “gluons” Isotopes Isotopes are atoms of the same element having different masses due to varying numbers of neutrons. Isotope Protons Electrons Neutrons Hydrogen–1 (protium) 1 1 0 Hydrogen-2 (deuterium) 1 1 1 Hydrogen-3 (tritium) 1 1 2 Nucleus Atomic Masses Atomic mass is the average of all the naturally isotopes of that element. Carbon = 12.011 Isotope Symbol Composition of the nucleus % in nature Carbon-12 12C 6 protons 6 neutrons 98.89% Carbon-13 13C 6 protons 7 neutrons 1.11% Carbon-14 14C 6 protons 8 neutrons <0.01% Atomic Number Atomic number (Z) of an element is the number of protons in the nucleus of each atom of that element. Element # of protons Atomic # (Z) 6 6 Phosphorus 15 15 Gold 79 79 Carbon Mass Number Mass number is the number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus of an isotope. Mass # = p+ + n0 Nuclide p+ n0 e- Mass # Oxygen - 18 8 10 8 18 Arsenic - 75 33 42 33 75 Phosphorus - 31 15 16 15 31 Molecules Two or more atoms of the same or different elements, covalently bonded together. Molecules are discrete structures, and their formulas represent each atom present in the molecule. Benzene, C6H6 Covalent Network Substances Covalent network substances have covalently bonded atoms, but do not have discrete formulas. Why Not?? Graphite Diamond Ions Cation: A positive ion • Mg2+, NH4+ Anion: A negative ion Cl-, SO42 Ionic Bonding: Force of attraction between oppositely charged ions. Ionic compounds form crystals, so their formulas are written empirically (lowest whole number ratio of ions). Periodic Table with Group Names The Properties of a Group: the Alkali Metals Easily lose valence electron (Reducing agents) React violently with water Large hydration energy React with halogens to form salts Predicting Ionic Charges Group 1: Lose 1 electron to form 1+ ions H+ Li+ Na+ K+ Predicting Ionic Charges Group 2: Loses 2 electrons to form 2+ ions Be2+ Mg2+ Ca2+ Sr2+ Ba2+ Predicting Ionic Charges B3+ Al3+ Ga3+ Group 13: Loses 3 electrons to form 3+ ions Predicting Ionic Charges Caution! C22- and C4are both called carbide Group 14: Loses 4 electrons or gains 4 electrons Predicting Ionic Charges N3- Nitride P3- Phosphide As3- Arsenide Group 15: Gains 3 electrons to form 3- ions Predicting Ionic Charges O2- Oxide S2- Sulfide Se2- Selenide Group 16: Gains 2 electrons to form 2- ions Predicting Ionic Charges F1- Fluoride Br1- Bromide Cl1-Chloride I1- Iodide Group 17: Gains 1 electron to form 1- ions Predicting Ionic Charges Group 18: Stable Noble gases do not form ions! Predicting Ionic Charges Groups 3 - 12: Many transition elements have more than one possible oxidation state. Iron(II) = Fe2+ Iron(III) = Fe3+ Predicting Ionic Charges Groups 3 - 12: Some transition elements have only one possible oxidation state. Zinc = Zn2+ Silver = Ag+ Writing Ionic Compound Formulas Example: Barium nitrate 1. Write the formulas for the cation and anion, including CHARGES! 2. Check to see if charges are balanced. 2+ ( Ba NO3 ) 2 3. Balance charges , if necessary, using subscripts. Use parentheses if you need more than one of a polyatomic ion. Not balanced! Writing Ionic Compound Formulas Example: Ammonium sulfate 1. Write the formulas for the cation and anion, including CHARGES! 2. Check to see if charges are balanced. ( NH4+) SO42- 3. Balance charges , if necessary, using subscripts. Use parentheses if you need more than one of a polyatomic ion. 2 Not balanced! Writing Ionic Compound Formulas Example: Iron(III) chloride 1. Write the formulas for the cation and anion, including CHARGES! 2. Check to see if charges are balanced. 3. Balance charges , if necessary, using subscripts. Use parentheses if you need more than one of a polyatomic ion. Fe3+ Cl- 3 Not balanced! Writing Ionic Compound Formulas Example: Aluminum sulfide 1. Write the formulas for the cation and anion, including CHARGES! 2. Check to see if charges are balanced. 3. Balance charges , if necessary, using subscripts. Use parentheses if you need more than one of a polyatomic ion. 3+ Al 2 2S 3 Not balanced! Writing Ionic Compound Formulas Example: Magnesium carbonate 1. Write the formulas for the cation and anion, including CHARGES! 2. Check to see if charges are balanced. Mg2+ CO32They are balanced! Writing Ionic Compound Formulas Example: Zinc hydroxide 1. Write the formulas for the cation and anion, including CHARGES! 2. Check to see if charges are balanced. 2+ Zn 3. Balance charges , if necessary, using subscripts. Use parentheses if you need more than one of a polyatomic ion. ( OH- )2 Not balanced! Writing Ionic Compound Formulas Example: Aluminum phosphate 1. Write the formulas for the cation and anion, including CHARGES! 2. Check to see if charges are balanced. 3+ Al PO4 3- They ARE balanced! Naming Ionic Compounds • 1. Cation first, then anion • 2. Monatomic cation = name of the element • Ca2+ = calcium ion • 3. Monatomic anion = root + -ide • Cl- = chloride • CaCl2 = calcium chloride Naming Ionic Compounds (continued) Metals with multiple oxidation states some metal forms more than one cation use Roman numeral in name PbCl2 Pb2+ is the lead(II) cation PbCl2 = lead(II) chloride Naming Binary Compounds Compounds between two nonmetals First element in the formula is named first. Second element is named as if it were an anion. Use prefixes Only use mono on second element P2O5 CO2 CO N2O = diphosphorus pentoxide = carbon dioxide = carbon monoxide = dinitrogen monoxide