Old English ( powerpoint )

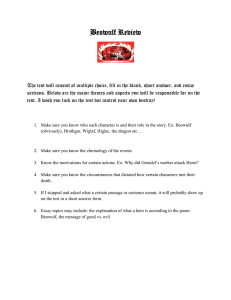

advertisement

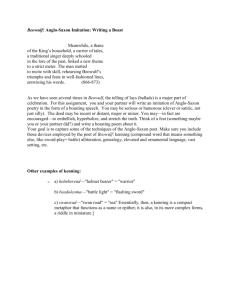

Oft him an-haga are gebideþ Metodes mildse þeah-þe he mod-cearig Geond lagu-lade lange scolde Hreran mid handum hrim-cealde sæ Wadan wræc-lastas. Wyrd biþ ful aræd. Swa cwæþ eard-stapa earfoþa gemyndig Wraþra wael-sleahta wine-maga hryre. Oft ic scolde ana uhtna gehwelce Mine ceare cwiþan nis nu cwicra nan ðe ic him mod-sefan minne durre Sweotule asecgan. Ic to soþe wat ðæt biþ on eorle indryhten þeaw ðæt he his ferhþ-locan fæste binde Healde his hord-cofan hycge swa he wille. Old English: mid-Ve - 1066 Middle English: 1066 - late XVe Modern English: XVIe - present Old English: mid-Ve – 1066 (aka Anglo-Saxon) •the language of Beowulf and the Wanderer •Germanic, hence heavily inflected and synthetic •special symbols invented by Latin-writing scribes: •thorn(þ), eth(ð), asc(æ) •many survivals (80+% of 1000 most common words) Middle English: 1066 - late Xve Modern English: XVIe – present Roman invasion & occupation (43-c.410) Germanic invasions (c.450): Angles, Saxons, Jutes Roman invasion & occupation (43-c.410) Viking raids (9th c.) Germanic invasions (c.450): Angles, Saxons, Jutes Roman invasion & occupation (43-c.410) Viking raids (9th c.) Germanic invasions (c.450): Angles, Saxons, Jutes Norman conquest (1066) Roman invasion & occupation (43-c.410) Old English: mid-Ve – 1066 •the language of Beowulf and the Wanderer •Germanic, hence heavily inflected and synthetic •special symbols invented by Latin-writing scribes: •Thorn(þ), eth(ð), asc(æ) •Many survivals (80+% of 1000 most common words) Middle English: 1066 - late Xve •Radical decline in inflections and declensions; hence more analytic •Extensive borrowings from French and Latin •Chaucer / Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Modern English: XVIe – present Old English: mid-Ve – 1066 •the language of Beowulf and the Wanderer •Germanic, hence heavily inflected and synthetic •special symbols invented by Latin-writing scribes: •Thorn(þ), eth(ð), asc(æ) •Many survivals (80+% of 1000 most common words) Middle English: 1066 - late Xve •Radical decline in inflections and declensions; hence more analytic •Extensive borrowings from French and Latin •Chaucer / Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Modern English: XVIe – present •Great Vowel Shift •Shakespeare / Milton •OE/ME/ModE compared Old English Poetry •roughly 30,000 lines survive, mostly in 4 MSS, all c. 1000 •Exeter Book (Wanderer, Seafarer, Deor, riddles), •Junius MS (Genesis, Exodus, Daniel, Christ and Satan) •Vercelli MS (Dream of the Rood) •MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv. (Beowulf, Battle of Maldon) •originally oral poetry—hence formulaic, as we’ll see •three main modes: heroic, elegiac, religious •aa/ax pattern •Specialized poetic vocabulary and style •synonyms •periphrasis •variation •kennings The opening of The Wanderer in the 10thcentury Exeter Book (Exeter Cathedral Library MS 3501) The opening lines of Beowulf in MS Cotton Vitellius A.x ENGLISH 2310 FALL 2009 GRADY QUIZ #1 Match the names with the correct descriptions. (5 pts) ____ 1. Wealtheow A. Wife of Hrothgar ____ 2. Hygelac B. Father of Beowulf ____ 3. Heorot C. Thane of Hrothgar who insults Beowulf ____ 4. Unferth D. King of Geats; uncle of Beowulf ____ 5. Ecgtheow F. Mead-hall where Grendel attacks Old English Poetry •roughly 30,000 lines survive, mostly in 4 MSS, all c. 1000 •Exeter Book (Wanderer, Seafarer, Deor, riddles), •Junius MS (Genesis, Exodus, Daniel, Christ and Satan) •Vercelli MS (Dream of the Rood) •MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv. (Beowulf, Battle of Maldon) •originally oral poetry, written down only later •performed by a scop (Beowulf, 866-73) •formulaic, as we’ll see •three main modes: heroic, elegiac, religious •aa/ax pattern •Specialized poetic vocabulary and style •synonyms •God = God, dryhten, frea, hlaford, þeoden, wealdend, metode, weard, scyppend •Man = man, wer, gesið, ceorl, eorl, beorn, guma, hæleð, rinc, secg •periphrasis •variation •kennings Old English Poetry •roughly 30,000 lines survive, mostly in 4 MSS, all c. 1000 •Exeter Book (Wanderer, Seafarer, Deor, riddles), •Junius MS (Genesis, Exodus, Daniel, Christ and Satan) •Vercelli MS (Dream of the Rood) •MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv. (Beowulf, Battle of Maldon) •originally oral poetry, written down only later •performed by a scop (Beowulf, 866-73) •formulaic, as we’ll see •three main modes: heroic, elegiac, religious •aa/ax pattern •Specialized poetic vocabulary and style •synonyms •God = God, dryhten, frea, hlaford, þeoden, wealdend, metode, weard, scyppend •Man = man, wer, gesið, ceorl, eorl, beorn, guma, hæleð, rinc, secg •periphrasis •variation •kennings Specialized poetic vocabulary and style in Anglo-Saxon verse •Synonyms •Periphrasis •Variation •Kennings •Specialized poetic vocabulary and style Synonyms •God = God, dryhten, frea, hlaford, þeoden, wealdend, metode, weard, scyppend •Man = man, wer, gesið, ceorl, eorl, beorn, guma, hæleð, rinc, secg Periphrasis Variation Kennings •Specialized poetic vocabulary and style Synonyms Periphrasis Variation Kennings, i.e., metaphors, sometimes recondite Whale-road (10) Swan’s road (200) Unlocked his word-hoard (258) •Specialized poetic vocabulary and style Synonyms Periphrasis, i.e., paraphrase of names/titles A fiend out of hell (101) This grim demon (102) The God-cursed brute (121) The hall-watcher (142) That dark death-shadow (160) These reavers from hell (163) The Lord’s outcast (169) Variation Kennings •Specialized poetic vocabulary and style Synonyms Periphrasis Variation, i.e. repetition of sentence elements in apposition Then a powerful demon, a prowler through the dark, nursed a hard grievance. It harrowed him to hear the din of the loud banquet every day in the hall, the harp being struck and the clear song of the skilled poet…. (Beowulf 86-90) Kennings Formulae and other motifs in Anglo-Saxon poetry Ruin The Wanderer: “So this middle-earth wind-blown walls stand covered with frost-fall, storm-beaten dwellings. Wine-halls totter, the lord lies bereft of joy, all the company has fallen, bold men beside the wall.” Ubi sunt (“where are they?”) The Wanderer: “Where has the horse gone? Where the young warrior? Where is the giver of treasure? What has become of the feasting seats? Where are the joys of the hall? Alas, the bright cup! Alas, the mailed warrior! Alas, the prince's glory!” Beot (formal boast) Beowulf 631-41 Beowulf 2510-15 Formulae and other motifs in Anglo-Saxon poetry Ruin The Wanderer: “So this middle-earth wind-blown walls stand covered with frost-fall, storm-beaten dwellings. Wine-halls totter, the lord lies bereft of joy, all the company has fallen, bold men beside the wall.” Ubi sunt (“where are they?”) The Wanderer: “Where has the horse gone? Where the young warrior? Where is the giver of treasure? What has become of the feasting seats? Where are the joys of the hall? Alas, the bright cup! Alas, the mailed warrior! Alas, the prince's glory!” Beot (formal boast) Beowulf 631-41 Beowulf 2510-15 Flyting (charge/defense/countercharge) Beowulf 499-601 Formulae and other motifs in Anglo-Saxon poetry Ruin Ubi sunt (“where are they?”) Beot (formal boast) Flyting (charge/defense/countercharge) “beasts of battle” The Wanderer: War took away some, bore them forth on their way; a bird carried one away over the deep sea; a wolf shared one with Death; another a man sad of face hid in an earth-pit. Battle of Maldon: Now was combat near, glory in battle. The time had come when doomed men should fall. Shouts were raised; ravens circled, the eagle eager for food. On earth there was uproar. Beowulf, 3021-27 Formulae and other motifs in Anglo-Saxon poetry Ruin Ubi sunt (“where are they?”) Beot (formal boast) Flyting (charge/defense/countercharge) “beasts of battle” “shaking the spear” Battle of Maldon: Birhtnoth spoke, raised his shield, his slender ash-spear, uttered words, angry and resolute gave him answer: “Do you hear, seafarer, what this folk says? They will give you spears for tribute, poisoned point and old sword…” Offa spoke, shook his ash-spear: “Lo, you, Ælfwine, have encouraged us all, thanes in need…” Then Dunnere spoke, shook his spear; humble churl, he cried over all, bade each warrior avenge Birhtnoth. Beowulf, 234-6 Formulae and other motifs in Anglo-Saxon poetry Ruin Ubi sunt (“where are they?”) Beot (formal boast) Flyting (charge/defense/countercharge) “beasts of battle” “shaking the spear” “hero on the beach”? Beowulf, 569-81 Beowulf,-1963-1970 Formulae and other motifs in Anglo-Saxon poetry Ruin Ubi sunt (“where are they?”) Beot (formal boast) Flyting (charge/defense/countercharge) “beasts of battle” “shaking the spear” “hero on the beach”? arming of the warrior? Beowulf 1441-64 Formulae and other motifs in Anglo-Saxon poetry Ruin Ubi sunt (“where are they?”) Beot (formal boast) Flyting (charge/defense/countercharge) “beasts of battle” “shaking the spear” “hero on the beach”? arming of the warrior? The opening lines of Beowulf in MS Cotton Vitellius A.x