Madeleine Jackson Poster Psych. Day BEC edits.ppt -1

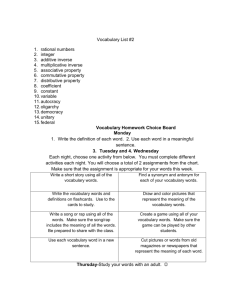

advertisement

Introduction Stress Responses in Children with Chronic Pain and Anxiety RECURRENT ABDOMINAL PAIN •Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) is the most common chronic pain complaint among children---between 10 and 20% of children experience RAP •To qualify for a classification of RAP, a child must have experienced at least 3 pain episodes in 3 months that impaired an activity (Apley, 1975) •Underlying mechanisms could be the same in these two clinical populations, but children present with different primary complaints •Children with RAP and anxious children are hypervigilant to perceived environmental threats (Boyer & Compas, 2006) Method Results Participants: •63 participants (29 male, 34 female): •21 RAP, 21 anxious, 21 healthy •Ages 8 to 16 (M = 11.64) •Groups matched for age and gender •Ethnic makeup of the sample: •71% white 19% African American, 3%Asian, 6% other, and 2% Hispanic •Participants excluded pair-wise for analyses Mean Heart Rate Across Time for Groups 100.00 Measures: 97.00 94.00 Well 91.00 RAP ANX 88.00 85.00 82.00 Baseline •Chronic stress plays a role in the maintenance of RAP and anxiety disorders (Walker, Garber, Smith, Van Slyke, & Claar, 2001) •RAP could be similar to anxiety in that they both involve an overall maladaptive reactivity to stress •Heart rate monitors •Psychological Stress Tasks •Serial Subtraction Task •Social Stress Interview •Physical Stress Task: Cold Pressor •Recovery Period •Questionnaires •Youth Self Report (YSR) •112-item parent-version of the YSR •assesses the parent’s perception of the child’s internalizing and externalizing problems in the past six months •Children with RAP and anxious children will react similarly to stress, reflected in their similar mean heart rates. These two groups will have higher mean heart rates than the healthy controls. •We will be able to predict the variance in selfreported psychological and somatic symptoms from physiological and self-reported stress reactivity beyond what group label tells us. 0.24 RAP Anxious Healthy 0.23 0.22 0.22 0.2 **p < .01, F (2, 54) = 5.59, p = .006 * 0.44 0.4 ** 0.54 0.47 ** 0.47 * ** ** 0.38 * * 0.35 0.35 + 0.3 ** ** 0.44 0.44 0.4 * YSR Anx/Dep CBCL Somatic Inv. Engage. 0.3 0.26 0.2 YSR Somatic 0 Stress Cold Recovery: Tasks: Pressor: Mean Mean Mean Heart Rate Heart Rate Heart Rate Pain Intensity Regression Equation Predicting Regression Equation Predicting YSR Anxious/Depressed Symptoms YSR Somatic Complaints T-Scores 66.0 Group Label (RAP, Anxious, Healthy) * 63.8 * RAP Anxious Healthy 60.1 58.0 56.8 56.8 56.0 56.5 54.6 54.0 53.6 β = .36* YSR Anxious/Depressed Symptoms β = -.16 53.4 50.0 CBCL Anx/Dep YSR Somatic Complaints * β = .51* β = .32 YSR Somatic Complaints β = .17 Mean Heart Rate (beats per minute) Mean Heart Rate (beats per minute) 52.4 YSR Anx/Dep Group Label (RAP, Anxious, Healthy) 63.3 61.8 62.0 β = .35* CBCL Somatic Complaints YSR Som: F (2, 34) = 7.30, p = .002 CBCL Anx/Dep: F (2, 60) = 12.1, p < .001 CBCL Som: F (2, 60) = 7.5, p = .001 Involuntary Engagement Proportion Scores (RSQ) At the final step: F (3, 28) = 6.44, p =.002, Final R2 = .41 * p < .05 Involuntary Engagement Proportion Scores (RSQ) At the final step: F (3, 28) = 2.43, p =.09, Final R2 = .21 * p < .05 Future Directions •Future studies should use a larger sample size to determine presence of differences in physiological reactivity, namely with the RAP group. •Future research should investigate parent perceptions of child difficulties to address the difference in parent and child reports of psychological and somatic symptoms. •Future analyses with the current sample will divide the groups based solely on the presence vs. absence of RAP and/or an anxiety disorder. •Future analyses with the current sample will also use additional physiological measures that were collected, including Galvanic Skin Response and Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia. References 70.0 •(3) Relations among the variables?: •Physiological reactivity will be positively correlated with psychological and somatic symptoms, and self-reported stress reactivity. 0.26 *p < .05, **p< .01, +p = .06 Descriptive Statistics: Psychological Symptoms •(2) Self-reported Stress reactivity: •Children with RAP will self-report being more stress reactive than the other two groups, as measured by the Involuntary Engagement scale of the RSQ. ** Baseline: Mean Heart Rate •57-item RSQ assess coping mechanisms in reference to age-appropriate social stressors •One scale of the RSQ is involuntary engagement, which includes physiological reactivity, emotional reactivity, intrusive thoughts, rumination, and impulsive action •(1) Physiological stress responses: ** 0.26 Involuntary Engagement Responses to Stress 0.6 •Responses to Stress Questionnaire (RSQ) Hypotheses 0.28 Correlational Data •Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) •Stress reactivity is associated with more somatic symptoms and symptoms of anxiety and depression (Thomsen & Compas, 2002) Recovery 0.3 Main Effect for Time: Wilks’ Lambda: F (3, 49) = 12.64, p < .001 Quadratic Effect for Time: F (1, 51) = 20.65, p < .001 •112-item questionnaire provides information on the participants’ perceptions of their psychological and somatic symptoms as well as level of functioning •Automatic stress responses play a role in both clinical populations: biological, psychological, and emotional reactions to perceived stressors Stress Tasks Cold Pressor Time Intervals Correlation Coefficients (r = ) STRESS REACTIVITY Self-reported Stress Reactivity Physiological Stress Reactivity Proportion Scores from the RSQ •RAP is comorbid with symptoms of anxiety and anxiety disorders (Blanchard & Scharff, 2002) •Children with RAP and anxious children may be more similar than different in reactivity to stress. •RAP (n = 21): 11 (52%) also met criteria for a DSM-IV anxiety disorder •Anxious (n = 21): 5 (24%) also met criteria for RAP •The results of this study provide support for the theory that the commonality between the clinical groups is stress reactivity. •Implications for intervention include focusing on altering automatic stress responses both by bringing physiological reactivity under control and focusing on the cognitive and behavioral factors on stress reactivity (e.g. intrusive thoughts, rumination, and impulsive action). Madeleine Jackson, Lynette Dufton, M.S., & Bruce E. Compas, Ph.D. Mean Heart Rate (bpm) PAIN AND ANXIETY Conclusions •Apley, J. (1975). The Child with Abdominal Pain (2nd edition) (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. •Blanchard, E. B., & Scharff, L. (2002). Psychosocial aspects of assessment and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in adults and recurrent abdominal pain in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 725-738. •Boyer, M. C., Compas, B. E., Stanger, C., Colletti, R. B., Konik, B. S., Morrow, S. B., et al. (2006). Attentional biases to pain and social threat in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31(2), 209-220. •Thomsen, A.H., Compas, B.E., Colletti, R.B., Stanger, C., Boyer, M., & Konik, B. (2002). Parent reports of coping and stress responses in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27, 215-226. Acknowledgments •Dr. Bruce E. Compas, for his constant encouragement and untiring attention and care to both this thesis and my learning experience. I attribute to him my love of psychology and research. •Lynette Dufton, M.S., the graduate supervisor of the project. I thank her for her extensive role in teaching me about research methods and data analysis, and for her generous nature as a consultant for so many questions. •Supported by a National Research Service Award from NIMH to Lynette Dufton.