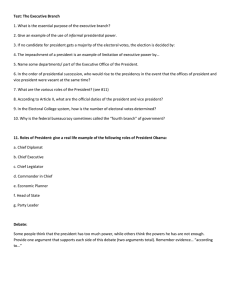

The U.S. Presidential Election Process: Undemocratic?

advertisement

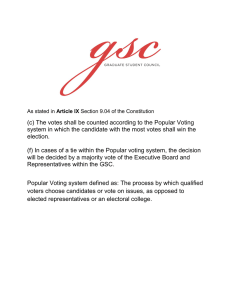

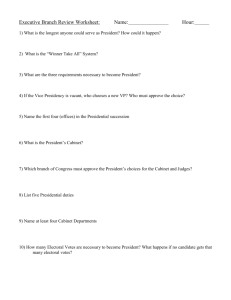

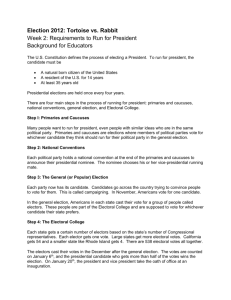

The United States Presidential Election Process: Undemocratic? The Bill of Rights Institute Chicago, IL October 2, 2008 Artemus Ward Department of Political Science Northern Illinois University aeward@niu.edu http://polisci.niu.edu/polisci/faculty/ward Introduction • The Electoral College system had led to presidents who do not win the popular vote. • The state-by-state electoral process that America uses to select its president has led to a situation where only about a dozen states are relevant. • Voter turnout is irrelevant, except in the small number of states that matter. • Issues and resources are skewed to “battleground” states. • The process for resolving an election where no candidate reaches a majority of electoral votes is even more undemocratic than the electoral college. The People’s Choice • Is the President of the United States “the people’s choice?” • In 1960, Richard Nixon received 34,108,147 votes to John F. Kennedy’s 34,049,976. • In 2000, Al Gore received 50,999,897 votes to George W. Bush’s 50,456,002. • Of Course Kennedy and Bush won in the electoral college but consider this, Nixon’s votes constituted only 49.3% of the total votes cast and Gore’s only 48.3%. • Nixon won the presidency in 1968 with 43.4% of the popular vote. • Bill Clinton won in 1992 with only 43% of the total votes. • Woodrow Wilson won in 1912 with 41.9%. • Abraham Lincoln won in 1860 with 39.8% of the popular vote—the all-time winner in the “least popular successful candidates” sweepstakes. The Electoral College • • • • • • • Presidential candidates and their campaign managers are not trying to win the popular vote. Instead, they attempt to put together a coalition of states that will provide a majority of the electoral votes. With 538 votes possible, it takes 270 to win. Main (4) and Nebraska (5) award their votes based on winning congressional districts and two for winning the statewide vote. 48 states and DC (3) have a winner-take-all system: whichever candidate gets the most votes in the state gets all of its electoral votes. This system creates the phenomenon of “battleground” states, which are those viewed as close to evenly split between the two parties, i.e. each party has a chance to win that state. Other “predictable” states—an increasing majority of them, roughly 2/3—are simply written off because their preferences are utterly predictable. In terms of candidate visits and campaign resources—particularly advertising—the vast majority of the population is ignored. For example, in the 2004 presidential campaign 99% of all advertising expenditures occurred in only 17 states with Florida and Ohio accounting for half. Add only three more— Iowa, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—and total rises to nearly ¾ of all advertising expenditures. 2008 electoral votes with predictable Republican “red” states, Democratic “blue” states, and grey “battleground” states. For an interactive map: http://www.270towin.com/ Implications of a State-by-State Campaign • • • A truly national election would increase turnout inasmuch as there would be more incentive for everyone to vote, in both (and other) parties. And, with increased turnout, we might get different winners than those that now win elections. Campaign issues would change. Because of the misfortune that most of America’s largest cities are in non-battleground states, almost no presidential candidate in years has made a truly serious speech about the plight of these cities. Democrats can take the states containing New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, and Los Angeles for granted, while Republicans in turn have almost no incentive to devote themselves to consideration of their plight. So issues such as prescription drugs for the elderly, support for Israel, and opposition to Cuba are magnified due to a preoccupation with the battleground state of Florida. Low-population states are advantaged while high-population states are disadvantaged. Why? Because each state gets two electoral votes regardless of population. Wyoming, with only 0.2% of the national population, has three times that weight in the Electoral College. California, on the other hand, with 12.2% of the national population, controls only 10.2% of the Electoral College votes. Consider the 2000 election. Al Gore won New Mexico (and 5 electoral votes) while losing Wyoming, Alaska, and North Dakota (nine electoral votes). Yet New Mexico has a larger population than those three states combined! “First Past the Post” • • • • Not only does the Electoral College system produce “winners” who fail to gain a majority of the popular vote, it also produces “winners” who do not even gain a majority of state popular votes. The so-called “first past the post” system means that a candidate only receive more votes than any other candidate to be awarded all the electoral votes in that state. Therefore, in a three-way race, a candidate with 33.4% of the statewide vote could gain all the electoral votes even though her competitors each won 33.3% of the vote. In an evenly divided four-way race, one would only need about 25.3% of the popular vote, and so on… Many countries have solved this dilemma by going to a runoff system that would assure that the winner indeed had received demonstrable majority support. Who Are the Electors? • • • • Though there may be party and state rules that “bind” electors to cast their ballots for the candidate with the most votes in that state, the Constitution appears to provide no bar to electors who wish to vote their conscience, rather than the party line. Indeed, a number of recent electors have case their votes for candidates other than the one they were “pledged” to support. For example, in 1976 one of the Washington state Republican electors pledged to Gerald Ford actually cast his vote for Ronald Reagan. Had only 5,559 voters in Ohio and 3,687 voters in Hawaii voted for Ford instead of Carter, with the one electoral vote “switch” from Ford to Reagan, For would have finished with 269 electoral votes to Carter’s 268 and Reagan’s 1. The House would have decided the election. In 1988, one of the electors pledged to Democrat Michael Dukakis cast his vote for Dukakis’ running mate Lloyd Bentsen. Resolving Deadlocks in the House: One State-One Vote • • • • • If no candidate receives 270 electoral votes, the House will decided among the top three candidates with each state casting a single vote. How should state delegations decide to cast their single vote? What if, in a very close state, representatives from districts that voted for X even though the state at large voted for Y decided to honor the preferences of their constituents—who, after all, will be casting judgment on them in the next election—instead of remaining loyal to their political party? The opportunities for mischief are great. One can easily imagine the kinds of promises that would be made to potential switchers, given the stakes of the decision. Consider the election of 1824. John Quincy Adams, who had received both fewer popular votes and fewer electoral votes than did his principle adversary, Andrew Jackson, nonetheless prevailed. The reason is that Henry Clay, who had come in fourth and therefore was not among the top three candidates who were available to the House for consideration, threw his support to Adams and, as a consequence, became secretary of state. Photograph of John Quincy Adams. 1848. • Why No Change? • • • • • • National public opinion has long supported the abolition of the entire Electoral College, yet nothing changes. Why? Two reasons: 1) The zeal of small states to protect their power within the system and 2) opposition from minorities who believe their power will be diluted. In 1969, the House voted 338-70 for a constitutional amendment establishing national direct election by popular vote. But in the Senate, southern and small state conservatives aligned to filibuster the proposal because they believed that reform would destroy the special influence the electoral college gives their constituencies. Ten years later, the Senate fell fifteen votes short of the necessary 2/3 when Democrats from New York, New Jersey, and Maryland led the opposition after black and Jewish organizations claimed that their supposed pivotal power in big swing states would be threatened. Even if congress were to pass such an amendment, consider the difficulty of obtaining ratification by ¾ of the states. It only takes 13 states to keep an amendment from being enacted. There are 14 states that reap dramatic benefit from the senatorial bonus: Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming. And this list does not include the additional 14 states whose percentage of the electoral vote is higher than their percentage of the national population. What incentive do these states have to ratify a constitutional amendment? Perhaps the biggest lesson from Bush v. Gore (2000) is that the current presidential election system will almost certainly remain in tact. The American people’s apathy toward and acceptance of that result demonstrates how difficult it would be to obtain a public groundswell for change. The Impermeable Article V? • “The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress; … [although] no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.” Alternatives to a Constitutional Amendment • • • • Article II, section 1 empowers each state to “appoint” its presidential electors in “such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct.” Article I, section 10 authorizes Congress to consent to “any agreement or compact” by one state with another. Large states could compact with one another to appoint electors who will be directed to cast their votes for the person who wins the greatest number of votes in the overall national election. The compact would not come into effect until enough states (which could be as few as the 11 largest states) to constitute a majority of the electoral votes had agreed to the compact. Upon Congress agreeing to the compact, the United States would in effect move to a popularly elected presidency. Congress could call for a new constitutional convention after 2/3 of the states petition Congress for such a move. The convention’s new constitution would only take effect if ratified in a national referendum. In the end, it is the American people that will determine whether such proposals are possible. The advent of new technologies, particularly the internet, have made it possible for relatively easy collective action. As a result, electronic petitions and websites have been launched to change the presidential election process. Will these work? Further Reading • • • • • http://www.270towin.com/ Edwards, George. 2005. Why the Electoral College is Bad for America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Eskridge, William N., Jr. and Sanford Levinson. 1998. Constitutional Stupidities, Constitutional Tragedies. New York, NY: New York University Press. Levinson, Sanford. 2006. Our Undemocratic Constitution: Where the Constitution Goes Wrong (and How We The People Can Correct It). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Levinson, Sanford, ed. 1995. Responding to Imperfection: The Theory and Practice of Constitutional Amendment. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.