Effects_of_Exchange_Rate_Movements.doc

advertisement

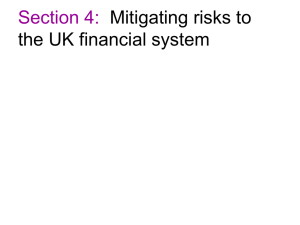

Effects of Exchange Rate Movements Sterling and Base Interest Rates Percent Trade-weighted index value for sterling in the foreign exchange market, daily value 6.0 5.5 5.0 4.5 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 5.5 5.0 4.5 Base Interest Rates 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 110 110 105 105 100 100 95 Index 6.0 90 95 Sterling Exchange Rate Index (trade-weighted) 90 85 85 80 80 75 75 70 70 Jan Mar May Jul 07 Sep Nov Jan Mar May Jul 08 Sep Nov Jan 09 Source: Reuters EcoWin The trade weighted exchange rate index has depreciated by twenty-five per cent over the last fourteen months. This is a significant change in the nominal exchange rate with both demand and supply-side effects: In this lesson we will consider some of the ways in which a fall in the exchange rate affects other macroeconomic variables: Who gains and who loses from a fall in the external value of sterling? Example UK farmers British farmers are in receipt of CAP subsidies which are fixed annually and paid in Euros at an exchange rate set at the level in September 2008. Publishers Pearson is a multinational publisher which marks school tests, produces learning materials and publishes the Financial Times and Penguin books. The group generates 60% of its sales in American dollars. The exchange rate has moved from $2 to the pound in 2007 to $1.44 at the 2008 year-end. Tourism Bed and breakfast businesses in London A glass manufacturer NJ Bradford is a business based in the West Midlands which supplies glass across a number of industries. Their main competitors come from China offering cheaper decorative and toughened glass products. Abattoirs in the Republic of Ireland In the Republic of Ireland, more than 60 per cent of all food products are exported. A UK airline That buys most of its fuel from the international petroleum markets and pays in US dollars. Estate agents selling prime London property British people living in France and Spain on sterling pensions Winner? Loser? Comment Sterling's fall hasn't helped trade deficit Source: Jeremy Warner, The Independent, Wednesday, 14 January 2009 If the weak pound was meant to provide a boost for British industry by making our manufacturers and service providers more competitive, there is scant evidence of it so far. To the contrary, the latest figures show a further widening in the trade deficit, with the ratio of export volumes to import volumes excluding oil deteriorating to its worst level since December 2007, when the pound was still relatively strong. Trade adjustments can take time to work their way through the system. There's a massive inventory correction going on across the world economy at the moment, and until it has played out, it is impossible to know what the long-term consequences of the currency collapse might be. In a world where it is an absence of demand and credit rather than an innate lack of competitiveness which is the root cause of our economic ills, it is not at all clear that a devalued sterling is going to help us very much. I'm glad to see I'm not alone in believing a weak currency to be not the unalloyed good the Bank of England and other British policymakers seem to think. As Simon Ward, chief economist at the asset management company New Star, points out, many manufacturers will have been constrained from taking advantage of greater price competitiveness by a lack of credit. Sterling's plunge will undoubtedly have contributed to this absence of credit by accelerating the withdrawal of foreign funds from the UK banking system. Credit in the UK has come to rely heavily in recent years on constant infusions of foreign capital. These have now largely gone. Meanwhile, import prices have been rising steeply, pushing up costs for UK manufacturers at a time when there is little demand for what they are producing. The Government hopes to ease the credit crisis with further guarantees for small business lending. Depending on the cost of this guarantee to the banks – the Government will extract a heavy price from the banks to safeguard the taxpayer from rising levels of default – this seems welcome enough, but it also smacks of "too little, too late". It's not just small companies but big ones too which are now suffering from the dearth of credit. Banks around the world are calling in their loans as they seek to shrink their balance sheets. Even relatively debt-free and, in normal times, perfectly viable companies are finding themselves affected by the phenomenon. In circumstances where they cannot refinance, many companies may find themselves forced to the wall or into an alternative fire sale of assets. The idea that devaluation is good for the UK economy is drawn largely from experience of the last recession, when recovery didn't finally seem assured until Britain was ignominiously jettisoned from the ERM. In fact, the economic recovery that then began had nothing whatsoever to do with a recovery in exports. Rather, it was led by domestic demand, which was starting to recover even before Britain left the ERM and was greatly enhanced by interest rate cuts thereafter. What's more, Britain had had two years of recession by the time this demand-led recovery began. There was much more slack in the economy to absorb the inflationary impact of sterling's fall than there is today. Ultimately, devaluation only works in making an economy more competitive by leading to a downward adjustment in real wages and therefore living standards. If of a puritanical frame of mind, you might think this entirely justified after years of credit-fuelled excess, but I see no reason to celebrate our new-found pauperism. Dollar-Sterling Exchange Rate GBP/USD US dollars per £1, daily closing exchange rate 2.1 2.1 2.0 2.0 1.9 1.9 1.8 1.8 1.7 1.7 1.6 1.6 1.5 1.5 1.4 1.4 1.3 1.3 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec 08 Jan 09 Source: Reuters EcoWin Euro - Sterling Exchange Rate Pence per Euro1 Value of one Euro, daily closing exchange rate 1.00 1.00 0.95 0.95 0.90 0.90 0.85 0.85 0.80 0.80 0.75 0.75 0.70 0.70 0.65 0.65 0.60 0.60 0.55 0.55 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 Source: Reuters EcoWin