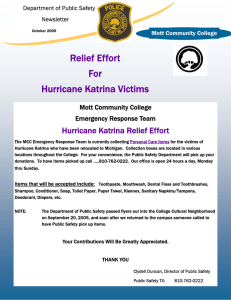

K After ATRINA Public Expectation and

advertisement