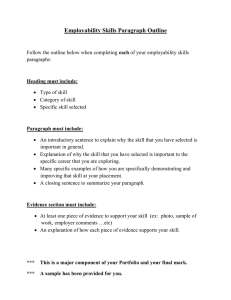

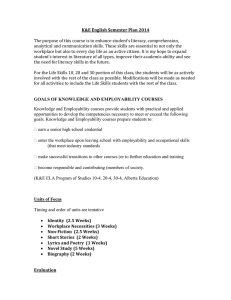

Learning & Employability Pedagogy for employability

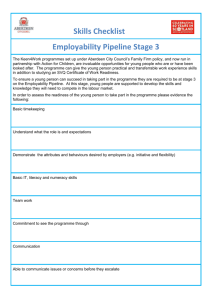

advertisement