A Survey of Issues Facing Federal Coordination for the Housing... Redevelopment of the Gulf Coast, U.S.

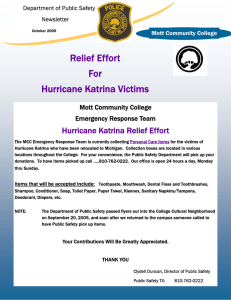

advertisement