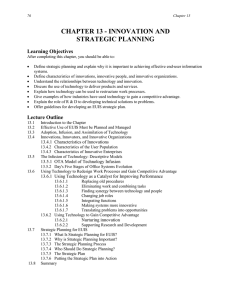

Chapter 1 Introduction to End-User Information Systems

advertisement