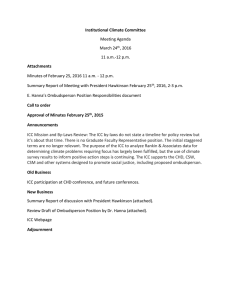

1

advertisement