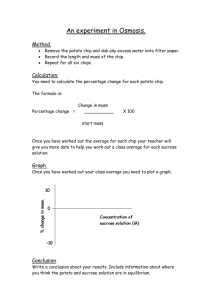

CHIP

advertisement