Introduction Ohio Medicaid Expansion Study

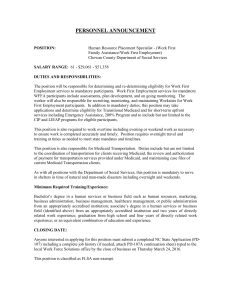

advertisement