Variation in Medicaid Eligibility and Participation among Adults: Implications for

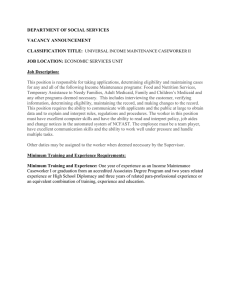

advertisement