Mercantilism and the American Revolution by Carole E. Scott

advertisement

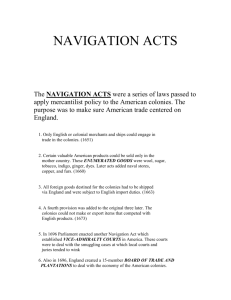

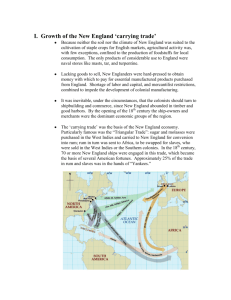

Mercantilism and the American Revolution by Carole E. Scott In its day, mercantilism was explained by its proponents, says economic historian Gerald Gunderson, as "a philosophy of nation building, a series of economic controls intended to strengthen a country and its colonies against other antagonistic empires. A major tenant of this view was self-sufficiency: sources of supply--raw materials, agriculture, and industry--should be developed domestically, or in colonies, to prevent interruptions by hostile foreigners. A large merchant marine was also deemed important. Cargo vessels of that era were designed to repel pirates and thus could be easily adapted to military roles during wars. Finally, the mercantilists were preoccupied with specie (gold and silver), then a universal foundation of money. Short of possessing gold mines, as Spain did, specie could be acquired with a 'favorable' balance of trade, that is, through earning foreign exchange by selling exports that brought in more money than was paid out for imports." Some economic historians, such as Jonathan Hughes, claim that there is nothing extraordinary about mercantilism, as the "use of subsidies, tax rebates, tariffs, and quotas to attempt to protect and encourage American industries at the expense of the rest of the world is standard modern practice. If every member of Congress and every president had the economic background and viewpoints of Adam Smith and David Ricardo (the great theorists of classical economics), we would not pursue such policies. But they do not, and we do pursue them, as do all other governments in the world today and as they did throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries." Even in medieval times in Europe local governments levied tolls (tariffs) on goods entering and leaving their territory. Local guilds formed by merchants and artisans fixed wages, prices, and other working conditions. Subsequently, these functions were transferred to the government, which sought to use its powers to promote economic growth and enrich the nation. Thus was born mercantilism, which added to existing economic nationalism to the already existing antagonism engendered by religious differences and rivalry among the kings of the various nations. Mercantilism lasted from the creation of strong central governments in the 15th century until the 19th century, however, mercantilist policies continue to be followed today. Some believe that the American revolution was an outgrowth of conflict between the colonies and England brought about by England's mercantilist policies. Mercantilism was at its height in the 17th and 18th centuries. Although the economic policies adopted in the nations of Europe were not identical, they shared sufficient common characteristics to consider each country's economic system as being of the same type. The objective of these policies was to maximize the nation's wealth. Wealth was defined in terms of gold; not the way Adam Smith defined it, which is the nation's ability to produce. Gold could be acquired either through a trade surplus or the obtaining of gold-bearing territory. Mercantilism involved the using the power of the state throughout the economy to enrich the state. Therefore, a mercantilist economy is a managed economy. England, France, Holland, and Spain all restricted their colonies' foreign trade. Subsidies and other assistance was employed to encourage the colonies to produce raw materials; while their right to produce manufactured goods that would compete with those produced by the mother country was restricted. The reason for doing this was to make the nation self-sufficient while enjoying the benefits of specialization. (Most colonial manufacturing took place in the Middle Colonies.) Colonies, by providing raw materials not found in the mother country and increasing the size of the domestic market made both substantial self sufficiency and specialization possible. Self-sufficiency reduced imports; thus making possible or making larger a trade surplus, which would add to the nation's gold stock. Specialization increased the nation's productivity. Navigation laws were common in mercantilist nations. These limited to native (citizens of mother country and its colonies) ships the right to bring goods into (imports) or take goods from (exports). This was expected to increase the size of the nation's merchant marine and earn additional specie through the selling of shipping services. 1 Mercantilist regulation in the thirteen colonies began in the 1620s, when steps were taken to prevent the importation into Britain of tobacco from Spanish and Dutch colonies. In the 1650s and 1660s the British Parliament passes a set of Navigation Acts. Foreign built or owned ships were forbidden to trade with the colonies, and ships that did engage in this trade must have crews, 3/4ths of whose members were British (from Great Britain or British North America). Various colonial exports were enumerated, that is, these goods had to be shipped to Britain, from which, if they were destined for other nations, they would be re-exported. This profited shippers and merchants in Great Britain. Colonial imports had to shipped through Great Britain. This made it easier for the British to collect import duties. In addition to benefiting Great Britain, these Acts were designed to injure the Dutch. In 1651, Holland declared war on Great Britain in order to get a 1651 Navigation Act repealed. It failed. Nonetheless, the Dutch maintained their maritime and commercial supremacy until well into the 18th century. Although the Navigation Acts did lead to a larger British merchant marine and increased its maritime trade, as Adam Smith pointed out, they imposed a cost on British consumers. These and other mercantilist policies provided some benefits to the colonies. Protection from foreign competition helped New England's ship building industry. South Carolina benefited from an indigo subsidy. North Carolina benefited from bounties on tar, pitch, turpentine, and lumber. Various colonial exporters benefited when they exported to Britain because competing goods from foreign nations were subject to tariffs theirs were not. On the other hand, colonists paid more than they otherwise would have for imports from foreign countries because they had to be shipped through Great Britain. (Tariffs levied on foreign goods, but not colonial goods, meant that British citizens paid more for imports than they otherwise would.) They paid more, too, for imported manufactured goods because they had to come through Britain. Southern planters, particularly rice and tobacco planters, bore much of the burden imposed by the requirement that the colonies' goods be exported to foreign nations via Great Britain, because most Southern exports went there, while smaller shares of the other two regions' exports went there. .New Englanders often evaded this cost through trading with foreign countries illegally. Enforcement of the Navigation Acts was not very effective until 1763, and it was after enforcement tightened that interest in gaining independence heightened. Some economic historians do not believe restrictions on colonial manufacturing imposed much of a burden on the colonies because they were in no position to establish much of a manufacturing sector due to the high cost of labor and capital; the small size of the colonial market, which precluded producing on a large enough scale to gain economies of scale; and the lack of necessary knowledge and skills. According to one historian, 1763 marked a turning point in the relationship between Britain and the colonies. Until then, the perceived benefits of Empire membership exceeded perceived costs. After 1763, both the colonists and the English became increasingly dissatisfied with the relationship. England had just emerged victorious in a long war with France. However, the war left Britain with a huge public debt and a growing conviction that the colonies must bear a greater share of the cost of maintaining the Empire. Because effective rates of taxation in England were many times higher than tax rates in the colonies, the English believed it was appropriate to raise revenues via a series of new taxes on the colonies and reformed colonial administrative practices to better enforce new and existing taxes. There were a series of revenue-raising measures passed by Parliament: the Sugar act of 1764, the Stamp and Quartering Acts of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767, the Tea Act of 1773, and others. "Before 1763," says a 2 historian, "only southerners had much reason to chafe under Empire regulations. But enforcement of the Sugar Act restrictions on trade with the West Indies alienated articulate northern merchants, as well, while the highly visible Stamp Act tax on documents irritated just about everyone in business." The Sugar Act sparked a boycott of imports from Great Britain. A boycott aimed at the Townsend Acts levied import duties on various colonial imports led to imports falling by one-third and Parliament repealing them. Opposition to the Stamp Act led to it be repealed. Therefore, the colonists learned that resistance worked. The British responded by increasing the legal authority of colonial administrators and by sending troops to back that authority. The objective of Parliament in passing the Sugar Act was to protect West Indian interests by placing taxes on foreign sugar and molasses. The Stamp Act was a way to collect a minor amount of revenue from the issuance of legal documents. The Currency Act (1764) was designed to make self limiting colonial issuance of paper money by establishing reserves for its redemption. The 1773 Tea Act ran into very strong resistance, including the Boston Tea Party. Outrage was generated in the colonies in 1774 by the passage of the Quebec Act, which limited the expansion of the colonies to the West. Various objectives have been put forth for this Act having been passed, including to stop the colonists from further encroaching on Indian lands and, as a result, initiating hostilities and protecting the trade of Hudson Bay Company. It infuriated colonists wanting to settle in the West and land speculators. It wasn't paying taxes or the amount they had to pay, which was relatively low, that seems to have angered the colonists most; instead, it was having no say in how much and in what way they would be taxed. Having a say was a right they felt entitled to as Englishmen. One economic historian (Jonathan Hughes) describes government then and today in this way: "Eighteenth-century government, like most governments now, was one of organized special interests gaining advantages for themselves at the expense of the unorganized. Subsidies here, taxes there, prohibitions, special grants of privilege, year after year, decade after decade, had produced the 'British government'." Questions: 1. According to the article, what are the three things that a country should strive for under mercantilism? 2. What are the origins of mercantilism? What was the lifespan of mercantilist policy? 3. According to Mercantilist philosophy, wealth is measure by what? How does this differ from Adam Smith’s definition of wealth? 4. Why is balance of trade important under the mercantilist system? 5. What were the three components of the English Navigation Acts? 6. Do you believe that the Navigation Acts represented a net loss or gain to the greater British Empire? Support your contention with a passage from the reading. 3