LESSONS THE UNITED STATES CAN LEARN FROM OTHER

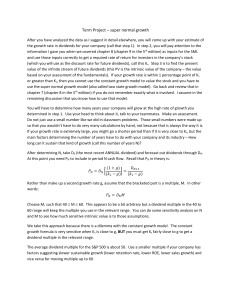

advertisement