Where Will They Go if We Go Territorial?

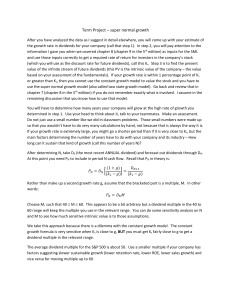

advertisement