Fee-for-Service Medicaid in Wisconsin:

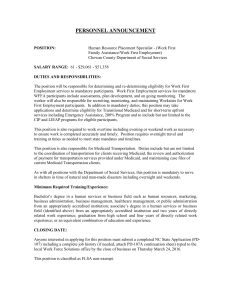

advertisement