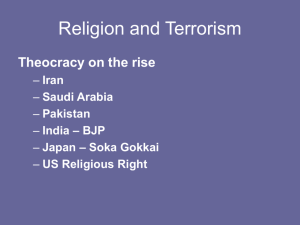

Deconstructing Iranian Speech: A Strategic Culture Analysis

advertisement