C S OMMUNITY ASE

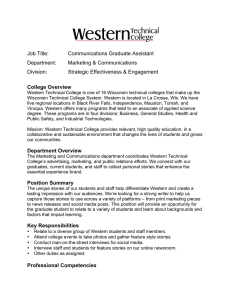

advertisement