β and S States Synechococcus elongatus

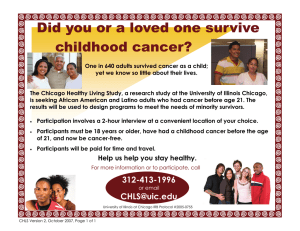

advertisement

J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 5995-6002 5995 β-Carotene to Chlorophyll Singlet Energy Transfer in the Photosystem I Core of Synechococcus elongatus Proceeds via the β-Carotene S2 and S1 States Frank L. de Weerd,* John T. M. Kennis, Jan P. Dekker, and Rienk van Grondelle Department of Biophysics and Physics of Complex Systems, DiVision of Physics and Astronomy, Faculty of Sciences, Vrije UniVersiteit, De Boelelaan 1081, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands ReceiVed: December 18, 2002; In Final Form: April 4, 2003 In this work, we describe the ultrafast excitation transfer dynamics of β-carotene in trimeric photosystem I preparations from Synechococcus elongatus. β-Carotene was excited with a femtosecond laser, and the changes in absorption were followed in the spectral region 490-740 nm. The lifetime of the β-carotene S2 (1Bu+) states is ∼60 fs, significantly shorter than that in nonpolar solution (150 fs), demonstrating efficient energy transfer to the chlorophylls from these states. About 70% of the remaining population of β-carotene S1 (2Ag-) states is not in contact with the chlorophylls (lifetime 10 ps), whereas ∼30% transfers its energy efficiently to chlorophylls (lifetime 3 ps). We ascribe the S1 transfer to a fraction of the β-carotenes (possibly the ones adopting a cis configuration) that exhibit favorable π-π stacking with nearby chlorophylls. We estimate that ∼70% of initial β-carotene S2 excitations is transferred to the chlorophylls, namely, ∼60% from S2 on a 60 fs time scale and ∼10% from S1 on a 3 ps time scale, making the S2 state to a major extent responsible for the larger yield of β-carotene to chlorophyll singlet energy transfer in comparison with the photosystem II core proteins. Introduction Carotenoids (Cars) play a major role in photosynthesis: on one hand, they quench singlet oxygen and chlorophyll (Chl) triplets (that can lead to the formation of singlet oxygen), while on the other hand, they harvest sunlight in a spectral region where Chls do not absorb. In the photosynthetic apparatus, β-carotene is the only carotenoid (Car) species bound to the core complexes (reaction center (RC) and core antenna) of photosystem I (PSI) and photosystem II (PSII). In both photosystems, excitation energy is transferred via the core antennas to the RC, where an ultrafast charge separation (∼picosecond) is initiated.1 In this study, we address the energy transfer from β-carotene to chlorophyll (Chl) in the PSI core complex of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus. In the crystal structure of the PSI core antenna complex of S. elongatus at 2.5 Å resolution, 96 Chl molecules and 22 Cars have been identified per monomeric unit.2 Six Chl molecules were assigned to the centrally positioned RC, whereas the remaining Chls are packed in a bowllike structure closely surrounding the RC, plus two peripheral domains, where the Chls are organized in two discrete layers near the stromal and luminal sides of the membrane. These peripheral domains possess a sequence homology with the PSII core antennas CP43 and CP47.3 The PSI antenna also contains the so-called “red” pigments, Chls with a longer transition wavelength than that of the primary electron donor P700 (for review, see ref 4). For S. elongatus, the subject of this study, red Chl pools denoted C708 and C719 (room temperature absorption maxima at 702 and 708 nm, respectively) were identified.5,6 Another pool was proposed to peak at 715 nm at 4 K.7 The C708 form may originate from Chl dimers in * To whom correspondence should be addressed. Tel: (+31) 20 4447934. Fax: (+31) 20 4447999. E-mail: weerd@nat.vu.nl. the inner ring and the C719 form was proposed to arise from a tightly coupled trimer in the periphery.2,6,8-10 Of the 22 Cars in the crystal structure, 21 were modeled as complete β-carotenes. These β-carotenes showed several isomerization states: for 16 β-carotenes, an all-trans configuration was found, whereas five β-carotenes adopted a variety of configurations containing one or two cis bonds. All 22 Cars are in van der Waals contact (<3.6 Å) to 60 Chl headgroups, suggesting the possibility of efficient Car to Chl excitation energy transfer (EET) and efficient quenching of Chl triplets.2 Like all Cars found in the photosynthetic apparatus, β-carotene has several low-lying excited singlet states: transitions between S0 (1Ag-, ground state) and S1 (2Ag-) are one-photon forbidden, and generally the S1 state becomes populated by internal conversion (IC) from higher states.11 The energy of the S1 state is hardly influenced by the environment and for β-carotene is estimated to be at ∼700 nm, which is slightly lower than the lowest excited singlet state of Chl (∼680 nm).12-14 The β-carotene S1 state has a lifetime of ∼10 ps in a range of solvents (e.g., see ref 15). The S0 f S2 (1Bu+) transition is one-photon allowed and responsible for the characteristic strong visible absorption of β-carotene (400-520 nm). As a result, from dispersive interactions, the solvent can shift the energy of the β-carotene S2 state and also change the S2 lifetime between 120 and 180 fs.15 In the weak-coupling limit, the rate of excitation energy transfer (EET) between pigments is proportional to the square of the interaction energy and to the overlap between the donor emission and the acceptor absorption (Förster energy transfer).16 Both the Car S0 f S2 and Car S0 f S1 transitions can exhibit a large Coulombic interaction with the Chl electronic transitions. The Car S0 f S2 transition interacts mainly through dipoledipole coupling,17-19 and the Car S0 f S1 transition, despite its forbidden nature, may show significant interaction due to contributions of higher-order terms in the multipole expansion 10.1021/jp027758k CCC: $25.00 © 2003 American Chemical Society Published on Web 05/20/2003 5996 J. Phys. Chem. B, Vol. 107, No. 24, 2003 of the transition charge density.17-20 Although EET from the Car S1 and S2 states to the Chls has to compete with fast internal conversion, energy transfer from both states can be fast in photosynthetic antennas where the relevant energy levels are well positioned. In some cases, the total quantum efficiency of the Car to Chl energy transfer may be as high as 100%.11 However, in the PSII core, the efficiency of β-carotene to Chl EET is rather low (20-40%).21-23 In contrast, fluorescence excitation spectra of the core of PSI from Synechocystis PCC6803 at 77 K show a high transfer yield of about 85%.24 In a fluorescence upconversion study on S. elongatus an overall quantum yield higher than 90% was estimated. It was argued that ∼60% of the initial Car S2 excitations is transferred to the Chls via S2 (on a ∼100 fs time scale) and ∼35% via S1 (on a ∼1 ps time scale).25 In this study, we present Car excited-state lifetimes in the PSI core of S. elongatus as inferred from (sub)picosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. It is concluded that in these PSI cores the lifetime of the Car S2 states is significantly shorter than that in solution, suggesting efficient transfer from the Car S2 states. About 70% of the remaining population of Car S1 excited states decays on a 10 ps time scale and is not in contact with the Chls, whereas ∼30% does transfer its energy efficiently to Chls (decay on a 3 ps time scale). Experimental Section Sample Preparation. Trimeric core particles of PSI were purified from S. elongatus as described elsewhere.26 The sample was dissolved in a buffer containing 0.05% (w/v) n-dodecylβ,D-maltoside (β-DM), 20 mM CaCl2, 20 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES, pH 6.5). To obtain samples with open RCs (P700-reduced), 10 mM sodium ascorbate and 50 µM phenazine metasulfate (PMS) were added. Under these conditions, it was determined that P700+ is reduced with a time constant of ∼2 ms.6 The optical density over the 1 mm path length of the cuvette was ∼0.4 at 400 nm, ∼0.1 at 508 nm, and ∼0.4 in the Qy maximum. Transient Absorption. Absorption difference spectra were recorded with a femtosecond spectrophotometer, described in detail elsewhere.27 In short, the output of a Ti:sapphire oscillator was amplified by means of chirped pulse amplification (Alpha1000 US, B. M. Industries), generating 100 Hz, 800 nm, 60 fs pulses. Single-filament probe white light was generated in a 2 mm sapphire plate. To minimize the chirp, parabolic reflectors were used to recollimate and focus the probe light in the sample. Pump pulses were centered at either ∼400 nm or ∼508 nm. Pump light at ∼400 nm was obtained by doubling the ∼800 nm fundamental (∼10 nJ/pulse); pulses around 508 nm were produced in a home-built, noncollinear optical parametric amplifier, and a 12 nm (fwhm) bandwidth was obtained after prism compression down to ∼40 fs (∼30 nJ/pulse). The magic angle spectra were obtained by rotating the polarization of the pump with a Berek polarization compensator (New Focus, 5540). Time-gated spectra were recorded with a home-built camera consisting of a double diode array read out at the laser frequency (100 Hz). Typically 800 difference absorbance spectra were averaged per delay. The chopper frequency was set such that the excitation beam was blocked every other shot. As a result, the sample was excited every 20 ms. The cuvette (1 mm path length) was shaken to refresh the sample from shot to shot. Dispersion curve and instrument response width were characterized by measuring the optical Kerr effect in water. Steady-state absorption spectra were measured before and after the experiment and were virtually identical. de Weerd et al. Figure 1. Absorption spectrum at room temperature of trimeric PSI core complexes from S. elongatus used in this work. Arrows indicate the two excitation wavelengths. Data Analysis. The spectra were fitted with a global analysis fitting program.28 A sequential model with increasing lifetimes was assumed in which each species evolves into the next one. Note that these species-associated difference spectra (SADS) are not necessarily associated with “pure states” and are used to represent the time evolution present in the data. Dispersion within the probe continuum (measured as the optical Kerr effect in water) was fitted with a third-order polynomial. The dispersion was almost absent in the spectral region 650-740 nm (at most ∼20 fs), whereas a dispersion of ∼3 fs/nm was obtained down to 490 nm. The instrument response width is mainly determined by the uncompressed white light and was fitted from the Kerr measurements in water assuming a Gaussian function. The obtained width (fwhm) varied from 140 fs at ∼490 nm to 90 fs at ∼700 nm. Results The absorption spectrum of the trimeric PSI core complexes from S. elongatus at RT is shown in Figure 1. The S0 f S2 0-0 transition of β-carotene around 500 nm is well separated from the Chl absorption: More to the blue, absorption is due to the Soret band of Chl (on top of a small background of β-carotene). More to the red, absorption around 600 nm is due to Chl Qx and vibronic Chl Qy states. The Qy transition peaks at 678 nm, and a tailing of the spectrum up to 750 nm resulting from the red Chl absorption can be seen. The excited-state dynamics were measured at RT using two excitation wavelengths, as depicted in Figure 1: ∼508 nm (fwhm 12 nm), exciting almost exclusively β-carotene, and around 400 nm, exciting almost exclusively Chl. In both cases absorption difference spectra, relative to samples with open RCs, were recorded between 490 and 740 nm and for pump-probe delays up to ∼4 ns. Both upon 400 and 508 nm excitation, the excitation conditions were such that about three excitations were created per monomer. Note that in the latter case the amount of Chl excitations was probably less than in the former case because of losses in the EET process from Car to Chl (see below). For a good understanding of the spectral evolution that occurs, we will discuss the dynamic processes among the multiple Chl excitations in the PSI trimer. Transfer between monomers most likely takes place on a tens of picoseconds time scale, which is longer than the trapping time in the case of multiple excitations (see below). Therefore, the chance that a particular monomer will get oxidized is almost 1 (>90%). In other words, the probability that in a particular monomer Chl is not excited is small (<10%). Therefore, we will assume in the following that β-Carotene to Chlorophyll Singlet Energy Transfer J. Phys. Chem. B, Vol. 107, No. 24, 2003 5997 Figure 2. Experimentally observed absorption difference spectra at room temperature upon 508 nm excitation (solid lines) and upon 400 nm excitation (dashed lines) after (from top to bottom) 1.0, 5, 30, 300, and 2300 ps. Pump and probe were set to magic angle. The dataset obtained upon 508 nm excitation has been scaled with a factor 0.67 such that the spectra at late delay times (P700+/A1-) overlap. Scatter region after 508 nm excitation (490-525 nm) has been deleted. the data at late delay times associated with the charge-separated state (P700+/A1-) have similar amplitude upon 400 and upon 508 nm excitation, and for that reason, we have scaled the data upon 508 nm excitation by a factor 0.67, such that the difference absorption associated with the charge-separated state (late delay times) precisely overlapped. We note that the difference in bleaching observed in the two experiments most likely originates from variation in pump/probe spot size and overlap. Absorption difference spectra at various delay times are shown in Figure 2 and traces at a few characteristic probing wavelengths in Figure 3 (solid lines, 508 nm excitation; dashed lines, 400 nm excitation). The region 490-525 nm upon 508 nm excitation was not taken into account because of scatter signals of the pump pulses that obscured the time-resolved data. Transient Absorption in the Chl Qy Region. The shapes of the difference absorption in the Qy region at late delay times coincide when comparing 400 and 508 nm excitation. The spectra (e.g., the 0.3 and 2.3 ns spectra in Figure 2) display the difference spectrum of P700+ minus P700 characterized by a minimum at 682 nm, a distinct positive peak at 690 nm, and a minimum at 700 nm (e.g., see Pålsson et al.29 and Savikhin et al.30 and references therein). When considering earlier delay times, the correspondence between both spectra remains quite strong down to a few picoseconds time delay. See, for instance, the Qy regions of the spectra at a pump-probe delay of 5 and 30 ps (Figure 2). Note that already the 5 ps spectra exhibit the characteristic features of the P700+ minus P700 difference Figure 3. Experimentally observed traces upon 508 nm excitation (solid lines) and 400 nm excitation (dashed lines) probed at (from top to bottom) 720, 708, 700, 682, 560, 545, and 530 nm. Pump and probe were set to magic angle. The dataset obtained upon 508 nm excitation has been scaled with a factor 0.67 such that the spectra at late delay times (P700+/A1-) overlap. A wavelength-dependent time-zero correction was performed to account for the dispersion present in the data (see text). Note that the time axis is linear between -0.5 and +0.5 ps and logarithmic at later delay times. spectrum (peak at ∼690 nm, minimum at ∼700 nm). Trapping in open reaction centers under annihilation-free conditions occurs in S. elongatus on 10 and 35 ps time scales.31 The apparently faster trapping observed here can be explained by the multiple Chl excitations per monomer. One can calculate that n excitations per monomer will speed up the trapping also by a factor n. When considering even earlier delay times (see, for instance, the 1.0 ps spectrum in Figure 2), the two data sets start to differ significantly. To obtain a better understanding of the spectral evolution that takes place, the time-dependent spectra were fitted to sequential models and typically four species with increasing lifetimes were required for a global fit of sufficient quality. These species-associated difference spectra (SADS) are dis- 5998 J. Phys. Chem. B, Vol. 107, No. 24, 2003 de Weerd et al. TABLE 1: Amount of Formation (+) and Disappearance (-) of Chl Excited States (Chl*), P700+, and A0- on Several Time Scales 400 nm excitation time scale (ps) +/-a Chl* <0.1 2-3 ∼5 ∼25 +3.0 -1.25 0.0 -1.25 +3.0 -1.25b -1.0 -0.75 ∞ -0.5 a P700+ +1.0 508 nm excitation A0- +/-a Chl* +1.0 -1.0 +1.5 0.0 0.0 -1.0 +1.5 0.0 -1.0 -0.5 -1.0 The change to the integrated difference absorption, where and SE). See text. b Annihilation only. -0.5 P700+ and Figure 4. Species-associated difference spectra (SADS) of the global fit in the Chl Qy region (650-740 nm) upon (A) 400 nm excitation and (B) 508 nm excitation. Each species evolves with the given time constant into the next one. played in Figure 4, panel A (400 nm excitation) and panel B (508 nm excitation). Upon 400 nm excitation, most absorption is due to the Soret transitions of the Chls; only a small fraction of the light is absorbed by the Cars. The first SADS (solid line, Figure 4A) resulting from the global fit represents the instantaneous spectrum. Because of the nonselective excitation at 400 nm, it resembles the (negative) steady-state absorption with a bleaching band around 678 nm. The first SADS is replaced by the second SADS (dot-dashed line, Figure 4A) on a 100 ( 30 fs time scale. This transition is associated with ingrowth of stimulated emission (SE) from the Qy transitions that were bleached upon excitation at 400 nm into the Chl Soret band. Upon 508 nm excitation, absorption of the pump pulses is due to β-carotene, and therefore, the fitted time-zero spectrum in the Chl Qy region (first SADS, Figure 4B) has a low amplitude. The transition from the first to the second SADS (ingrowth of bleaching/SE) takes place on a 150 ( 30 fs time scale. The observed time scale is somewhat slower than expected for efficient EET from the Car S2 states to the Chls (<100 fs), in case the Qy states are the energy acceptors. One possible explanation is delayed SE due to the transient population of Qx states, being intermediates in the EET process (see below). The shapes of the second SADS upon 400 nm and of the second SADS upon 508 nm excitation are very similar. We will now estimate the total number of Chl excitations contained in each second SADS, following our earlier assumption that at late times each monomer will be oxidized. The spectrum associated with the nondecaying charge-separated state is similar in both data sets (compare the fourth SADS in Figure 4A and A0- P700+ +1.0 -1.0 A0- comment +1.0 -1.0 Chl abs./Car S2 f Chl Car S1 f Chl/annihilation charge separation quenching of Chl* by closed RC/ reoxidation of A0long-lived state (bleaching only) have a contribution that is half that of Chl* (bleaching the fourth SADS in Figure 4B) and has an integrated amplitude that is ∼17% (400 nm excitation) and ∼32% (508 nm excitation) of that of the corresponding second SADS. Because A0- is reoxidized on a ∼30 ps time scale32 with the positive charge remaining on a single Chl,33 the nondecaying state (P700+/A1-) corresponds to the bleaching of a single Chl. Each second SADS (Figure 4A,B) represents bleaching and SE from several electronically excited Chls. Assuming similar integrated amplitudes for bleaching and SE, it follows that the number of Chl excitations contained in the second SADS is on average 3 upon 400 nm excitation, and on average 1.5 upon 508 nm excitation (see Table 1). Subsequently, the second SADS in each global fit is replaced by the third SADS (dashed lines, Figure 4) on a 2-3 ps time scale. During this transition, Qy transitions with the bleaching/ SE maximum centered at 683 nm are lost, while more bleaching/ SE in the red appears (maximal ingrowth at 711 nm). This spectral evolution includes the conservative equilibration between the bulk and mainly the red Chl pool at 702 nm (C708) that is known to occur in ∼4 ps, as obtained for the same species by means of streak camera measurements with picosecond resolution.31 Upon 400 nm excitation, the gain of bleaching/SE does not match the loss of bleaching/SE. As discussed above for the measured spectrum after 5.0 ps, the third SADS in Figure 4A and the third SADS in Figure 4B (maximal concentrations after ∼6 ps) have a P700+ minus P700 character. Because bleaching and SE of P700* is replaced by two bleaching bands (due to P700+ and A0-), trapping must be spectrally a more or less conservative process, which cannot account for the observed strong nonconservative character. The decay must therefore originate from annihilation in the PSI core antenna or quenching by the already closed RC or both. It has been discussed in the literature that the trapping kinetics by open and closed RCs is not much different.6,30 In contrast, upon 508 nm excitation, the spectral evolution on the 2-3 ps time scale is more or less conservative. Apart from the equilibration between bulk and red Chls, three time-dependent processes take place on this time scale: (i) The first is annihilation. It is discussed below that the decay on the 2-3 ps time scale after 400 nm excitation originates from annihilation of 1-1.5 out of the 3 excitations (see also Table 1). Because on average 2 times fewer excitations are present in the Chl pool upon 508 nm excitation, the annihilation probability in this case will be approximately 4 times smaller. (ii) The second process is EET from the Car S1 states to the Chls (see below). (iii) The third process is loss of Car S1 f SN excited state absorption (ESA). A tail of the Car S1 f SN ESA contributes to this spectral region, and significantly more of this S1 f SN ESA is present upon 508 nm excitation. The spectral changes associated with each of the three processes will be small (compared to the annihilation upon 400 β-Carotene to Chlorophyll Singlet Energy Transfer nm excitation) and are canceling one another. The net result is a more or less conservative transition from the second to the third SADS, in contrast to the nonconservative character upon 400 nm excitation. We conclude that probably the amount of EET from the Car S1 states to the Chls is small and that it is difficult to extract the precise contribution from the spectral evolution in the Chl Qy region following 508 nm excitation. In both spectral evolutions, the transition from the third to the fourth SADS (dotted lines, Figure 4), displaying losses centered at 687 and 708 nm, takes place on a 25 ( 5 ps time scale. This step can be ascribed to decrease of bleaching/SE by annihilation or quenching by P700+ or both of the remaining antenna excitations, equilibrated over the bulk (∼683 nm) and over the red (∼708 nm) Chl pool, and reoxidation of A0-, which is known to occur on a ∼30 ps time scale32 representing most of the loss of bleaching at 687 nm. Each fourth SADS in Figure 4A,B can be assigned to the P700+/A1- state (P700+ minus P700 difference spectrum) with bleaching minima at 682 and 700 nm (e.g., see Pålsson et al.29 and Savikhin et al.30 and references therein) and does not decay for pump-probe delays up to 4 ns. Following 400 nm excitation, we calculated that initially on average three Chl excitations are present per PSI monomer. One of those excitations triggers the formation of P700+/A0- on a few to 10 ps time scale. The other, on average, two Chl excited states disappear on a fast (∼3 ps) and on a slow (∼23 ps) time scale. Most likely the fast decay is dominated by annihilation (more excitations present, most RCs still open), whereas the slower decay, when fewer excitations are present, is dominated by quenching by closed RCs. The losses associated with the ∼3 ps component (decrease of integrated signal from second to third) and with the ∼23 ps component (decrease of integrated signal from third to fourth SADS) have about equal amplitudes. Because the slower transition also contains the reoxidation of A0-, we propose that upon 400 nm excitation on average ∼1.25 Chl excited states disappear on a fast and ∼0.75 on the slow time scale (see Table 1). We finally note that the annihilation/trapping kinetics seems to be consistent with two to three interacting excitations per monomer, rather than six to nine excitations per trimer. In other words, intermonomer transfer is slow, in line with our earlier assumption. Transient Absorption in the Region 490-650 nm. Upon 508 nm excitation, the Cars dominate the transient spectra in the spectral region 490-650 nm. Following SE from the Car S2 state (see traces probed at 530, 545, and 560 nm in Figure 3), Car S1 f SN ESA starting at ∼500 nm and displaying a clear peak at ∼565 nm can be seen. Also a small and rather flat Chl ESA is present. Upon 400 nm excitation, the broad band peaking at ∼525 nm is ascribed to a Chl ESA (see below), though a sideband at ∼565 nm originating from a small amount of Car S1 f SN ESA can still be seen (Figures 2 and 3). 400 nm Excitation. The spectral evolution following 400 nm excitation was fitted to a sequential model, and five species with increasing lifetimes were required for a good global fit. These SADS are displayed in Figure 5. As can be seen from the measured traces in Figure 3, although a small bleaching of Qx and vibronic Qy bands is expected in the red part of this spectral region, the instantaneous signals are approximately zero. To facilitate the global analysis, the first SADS was therefore set to zero (see Figure 5) and its lifetime (IC time to Qx/Qy) was fixed to 100 fs, as estimated from the global analysis in the Chl Qy region (Figure 4A), which is similar to the relaxation J. Phys. Chem. B, Vol. 107, No. 24, 2003 5999 Figure 5. SADS of the global fit in the region 490-650 nm upon 400 nm excitation. Each species evolves with the given time constant into the next one. The spectrum of the first SADS was set to zero (see text). Because of overlapping time scales, the amplitude of the second SADS is uncertain (see text). time reported by Donovan et al.34 The subsequent spectral evolution is a decay of ESA on several time scales. The second (decay 0.2 ( 0.1 ps), third (decay 4 ps), and fourth SADS (decay 32 ps) have in common an ESA with a maximum at ∼525 nm and, especially in the third SADS, some Car S1 f SN ESA centered at ∼565 nm. These findings are clearly different from those in the PSII core antenna proteins CP43 and CP47, for which mainly an ESA band around ∼565 nm (Car S1 f SN ESA) was observed in this spectral region upon 400 nm excitation.23 We cannot completely exclude the possibility that the ∼525 nm band observed here represents ESA from a so far unidentified β-carotene state, for instance, the S* state recently observed for several Cars.35,36 However, because the decay times (with the exception of the subpicosecond decay) compare well with those observed in the Chl Qy region, we assign the band at ∼525 nm to a Chl ESA, and possibly some absorption due to P700+ or A0- or both. This large ESA band, which is not present in the CP43 and CP47 proteins, possibly originates from specific couplings within the bulk Chls in the PSI core. The transition from the second to the third SADS occurs in 0.2 ( 0.1 ps. The extent of decay during this transition (in other words, the amplitude of the second SADS) is highly uncertain because the concentration profiles of decay and ingrowth are overlapping extensively. Nevertheless, the subpicosecond decay process can also be inferred from the steeper rise in the 530 nm trace compared to the 545 and 560 nm traces (Figure 3, 400 nm excitation). One possibility is that this decay component represents the transient population of Chl Qx states with larger ESA than the Chl Qy states being formed. The transition from the third to the fourth SADS takes place on a 4 ps time scale. This decay component represents the mixture of annihilation and trapping by the RC as was already discussed for the Chl Qy region (2-3 ps time scale), together with the decay of the Car S1 states on a longer time scale. The latter states are populated by IC from the Car S2 states that are directly excited, though much less than Chls, by the 400 nm pump pulses. The transition from the fourth to the fifth SADS takes place on a 32 ps time scale and represents a decay process similar to the 23 ps component in Figure 4A. The fifth SADS (not decaying) represents the charge-separated state (P700+/A1-) and displays an ESA in this spectral region. 508 nm Excitation. When probing in the region 525-650 nm (see, for instance, traces probed at 530, 545, and 560 nm in Figure 3), the instantaneous SE from the Car S2 state is followed by the appearance of Car S1 f SN ESA on a time scale of less than 100 fs. We have compared the decay of the Car S1 f SN 6000 J. Phys. Chem. B, Vol. 107, No. 24, 2003 Figure 6. Experimentally observed traces probed at (A) 570 and (B) 540 nm upon 508 nm excitation of PSI (dashed lines), compared with the corresponding data in CP43, CP47, and the PSII RC (solid lines).23 Both insets display the region -1 to +5 ps. Figure 7. SADS of the global fit in the region 525-650 nm upon 508 nm excitation. Each species evolves with the given time constant into the next one. ESA with kinetic traces observed in the isolated subcomplexes of the PSII core (CP43, CP47, and the RC) that bind the same pigments as the PSI core. In those complexes, following the decay of the Car S2 state, the kinetics in the Car S1 f SN ESA can be described by (i) a conservative relaxation process observed as a loss of red (>580 nm) and a gain of blue (<580 nm) ESA on a 0.4 ps time scale and (ii) an overall decay of the Car S1 f SN ESA on a ∼10 ps time scale.23 Figure 6 shows the experimentally observed traces probed at (A) 570 and (B) 540 nm for PSI (dotted lines), together with the traces observed in CP43, CP47, and the PSII RC (solid lines). We first point to the clear difference in subpicosecond kinetics between the 540 and 570 nm traces for PSI (see insets). For the subcomplexes of the PSII core, all 540 and 570 nm traces display an ingrowth on a ∼0.4 ps time scale associated with the conservative relaxation process in the Car S1 f SN ESA. In contrast, for PSI cores, the trace at 540 nm displays a clear decrease of absorption on this time scale. A second perhaps more interesting feature is the faster overall decay of the ESA in PSI compared to the subcomplexes of the PSII core. The kinetics in the PSI core can be described by a biexponential decay of the Car S1 states as indicated by a global analysis fit of the data upon 508 nm excitation (Figure 7). The spectral evolution was fit to a sequential model and six species with increasing lifetimes were required for a good description. These SADS are displayed in Figure 7. The first de Weerd et al. SADS represents the difference spectrum at time zero, which can be ascribed to SE from the Car S2 states. The first SADS is replaced by the second SADS on a 60 ( 20 fs time scale. Apparently, the Car S2 lifetime is clearly shortened compared to solution (between 120 and 180 fs15), suggesting a significant amount of EET to the Chls from the Car S2 states. The second SADS displays an ESA that to a large extent can be ascribed to Car S1 f SN ESA. A further spectral evolution occurs on a 0.3 ( 0.1 ps time scale (transition from second to third SADS); ESA on either side of the Car S1 f SN ESA maximum (∼570 nm) disappears. As mentioned above, a loss of red and gain of an equal amount of blue ESA can be expected, as observed for many Cars (e.g., lycopene, zeaxanthin, neurosporene, and spheroidene),36-38 including β-carotene in solution37,39 and β-carotene in the PSII core.23 Apparently, a loss of ESA in the 530-550 nm region is present in the PSI core of S. elongatus superimposed on the spectral relaxation in the Car S1 state (see also the subpicosecond dynamics in Figure 6, discussed above). As in the discussion of the data upon 400 nm excitation, we assign this observation to a loss of Chl ESA on this time scale. Then, in case a transient population of Chl Qx states is responsible for the subpicosecond decay, the Car S2 states transfer to a significant extent to the Chl Qx states. The subsequent decay of the Car S1 f SN ESA occurs on a 3 ps (transition from third to fourth SADS) and on a 10 ps time scale (transition from fourth to fifth SADS). As a most likely explanation for the biexponential decay, we suggest that one Car pool is able to transfer its S1 energy to the Chls (on a 3 ps time scale), whereas another pool of Cars does not transfer its S1 energy to the Chls and gives rise to a 10 ps decay due to IC to the ground state, as observed in CP43, CP47, and the PSII RC.23 When quantifying the amount of decay associated with the 3 and 10 ps components, one should construct decay-associated difference spectra (DADS), rather than subtracting the consecutive species-associated difference spectra (when time scales are far apart, as is the case in Figure 4, both methods will yield the same result). Because the fifth and sixth SADS have small amplitudes, the third DADS can be constructed according to (Supporting Information in ref 40) DADS3 ≈ SADS3 - ( ) k3 SADS4 k3 - k4 (1) Then, we can calculate that the 3 ps decay equals 30% of the total, and hence, the 10 ps decay equals 70% of the total. The transition from the fifth to the sixth SADS (∼50 ps) is associated with a very small loss of ESA from Chl* or A0- or both. This corresponds to the transition from the third to the fourth SADS in Figure 4B (27 ps). Here, a longer lifetime is obtained because some loss of ESA from Chl* or A0- is accounted for in the 10 ps component. The small Chl ESA confirms that the ESA in this spectral region almost exclusively originates from the Cars. The sixth SADS corresponds to the nondecaying difference absorption of the charge-separated state (P700+/A1-). Discussion Transfer from the Car S2 States. The Car S2 lifetime obtained in this work (60 ( 20 fs, see Figure 7) is somewhat shorter than that obtained from the upconverted Car fluorescence at 580 nm for S. elongatus in ref 25 (105 fs), but similar to the value obtained in a recent upconversion experiment on PSI cores with better time resolution.41 Our Car S2 lifetime is shorter than β-Carotene to Chlorophyll Singlet Energy Transfer those in the CP43 and CP47 complexes of spinach (80 ( 20 fs, inferred from transient absorption,23 and a value similar to 80 fs was inferred from upconverting the Car fluorescence41). The IC time for β-carotene ranges between 120 and 180 fs, depending on the polarity and polarizability of the environment.15 The PSI core proteins represent a polarizable medium, as can be inferred from the downshifted S2 energies of β-carotene. The CP47 protein was proposed to be nonpolar.42 Because CP47 is homologous to a peripheral domain of the PSI core antenna,3 we suggest that also the PSI core presents a nonpolar environment. Using the refractive index reported for CP47 by Renge et al. (n ) 1.51)42 and the relation between the S2 lifetime and the polarizability for nonpolar media given by Macpherson et al.,15 we find that the expected IC time in the PSI core is 150 fs. Obviously, the Car S2 lifetime in the PSI core of S. elongatus is significantly shortened with respect to solution. Using values of 60 fs for the Car S2 lifetime and 150 fs for the Car S2 f S1 IC time, we find that the calculated quantum yield of energy transfer is 60%, which is higher than the total yield of Car to Chl EET in CP43 and CP47 (∼35%).23 The energy transfer in CP43, CP47, and the PSI core follows from the spectral overlap between the donor (Car S2) emission and acceptor (Chl Qx or Qy or both) absorption and the dipoledipole coupling between these states. In the absence of significant spectral overlap between the Car S2 emission and the vibronically relaxed Qy absorption (∼680 nm), we propose that the Qx or vibronic Qy states or both accept the excitations from the Car S2 states. An indication for the involvement of the Qx state follows from an ESA band at 520-540 nm, which was ascribed to Chl. Decrease of this Chl ESA is present on the time scale of 0.2-0.3 ps (following 400 nm excitation but more pronounced following 508 nm excitation). No decay on this time scale could be resolved in the Chl Qy region, suggesting that the population of Chl* does not decrease. A transient population of Qx states, however, can explain the observed decay. Note that following Car excitation Chl Qx states can only be populated from the Car S2 states. This suggestion is in line with the possible delayed SE in the Qy region; though the Stokes’ shift of the bulk Chls is small, hindering a precise interpretation of the data in the Qy region, we observedfollowing Car excitation-an ingrowth of the bleaching/SE (150 ( 30 fs, Figure 4B) slower than the Car S2 lifetime (60 ( 20 fs, Figure 7). However, a definitive conclusion concerning the involvement of the Qx states in the Car S2 to Chl EET in the PSI core of S. elongatus awaits further experiments. Transfer from the Car S1 States. From the biphasic decay of the Car S1 states, it was proposed that two pools of Cars exist, one pool that can (decay 3 ps) and one pool that cannot (decay 10 ps) transfer its S1 energy to the Chls. From the amplitudes of both components, it was proposed that ∼30% of the Car S1 states is “in contact” with the Chls. From the results of a target analysis on upconversion experiments on PSI cores, in which it was assumed that S1 transfers only to the bulk Chls, it was argued that in S. elongatus almost all Car S1 excitations are transferred to the Chls on a ∼1 ps time scale.25 This is at odds with the direct measurement of the Car S1 lifetimes and Car S1 contributions to the total Car to Chl EET process in this study. Kennis et al.25 noted, however, that the upconversion data were consistent with a model in which a fraction of the S1 states would not transfer its energy to the Chls, as we suggest now on the basis of the experiments described in this work. From the ∼3 ps lifetime (and 10 ps IC time) observed here, a quantum efficiency of EET from these transferring S1 states of ∼65% can be calculated. Then, taking a 40% IC yield from the Car S2 J. Phys. Chem. B, Vol. 107, No. 24, 2003 6001 to the S1 state, in total ∼10% of the initial S2 excitations will be transferred to the Chls via the S1 states, bringing the total efficiency to ∼70%. The above numbers were derived from the observed lifetimes of the Car excited states. We note that these lifetimes are not affected by the singlet-singlet annihilation because this annihilation occurs between the Chls. By comparing the kinetics in the Qy region upon 400 and 508 nm excitation, we suggested that the delayed Car S1 transfer equals at most a small fraction of the fast transfer via the Car S2 states. This is in line with the ratio of EET from S2 over EET from S1 as obtained from the Car excited-state dynamics (60/10). The value obtained for the total quantum yield of EET (∼70%) from Cars to Chls might be slightly higher because of transfer from “hot” Car S1 states on a few hundred femtosecond time scale. Such a process could not clearly be resolved in our experiment, and we conclude that transfer from “hot” S1 states is at most a small fraction of the total. Because most of the Car S1 states cannot transfer their energy, the total quantum yield of EET from the Cars to the Chls in the PSI core from S. elongatus is somewhat lower than that estimated for the same species by Kennis et al. (>90%, inferred from fluorescence upconversion),25 and for Synechocystis PCC6803 by Van der Lee et al. (∼85%, inferred from fluorescence excitation spectrum at 77 K).24 The 0-0 of the Car S0 f S1 transition is estimated to be at ∼700 nm, and the emission from the Car S1 state is broad,12-14 and therefore some overlap with the Chl Qy absorption is expected. Transfer to the Chls from the Car S1 states can then be explained by a Coulombic coupling but now (because of the forbidden nature of the Car S1 states) using higher-order terms in the multipole expansion of the transition charge density.17-20 We will now consider the possible reasons for the presence of the two Car (S1) pools identified above. We first mention the presence of red Chls in the PSI core and the effect on the overlap integral between the Car S1 emission and the Chl Qy absorption. Red Chls absorb at lower energy and seem better tuned to the Car S1 emission. Although the slightly different ratio of bulk versus red excitations between 5 and 30 ps upon 400 and 508 nm excitation (Figure 2 and trace at 720 nm in Figure 3) might suggest preferential transfer to red Chls, it is difficult to obtain support for such preferential transfer from our experimental data; the S1 transfer is only a small fraction of the S2 transfer, and the time scale of S1 transfer coincides with the equilibration between bulk and red Chls. Moreover, as mentioned above, also spectral overlap between the Car S1 emission (0-0 at ∼700 nm) and bulk Chl absorption (∼680 nm) is expected because the Car S1 state is very broad. For this reason, the effect of preferential transfer to red Chls from the Car S1 state cannot be large. Therefore, the Car S1 transfer heterogeneity most likely originates from differences in π-π stacking with nearby Chls, and we will now consider the possibility that the heterogeneity reflects different isomerization states of the Cars. We note that the fourth SADS in Figure 7 is approximately 5 nm blue-shifted compared to the third SADS. Though a blue shift over a few nanometers on a few picosecond time scale was also observed in CP43, CP47, and the PSII RC, we suggest the possibility that the cis Cars are responsible for the fast decay (and part of the blue shift). Different Car S1 f SN ESA maxima have been reported for β-carotene isomers: the 9-cis is 9 nm and the 13cis is 4 nm red-shifted compared to the all-trans configuration. All of these isomers display similar S1 lifetimes.43 In the crystal structure, the five cis isomers (∼25% of the total number of 6002 J. Phys. Chem. B, Vol. 107, No. 24, 2003 Cars) were modeled as 9-cis (2×), as 9,9′-cis (1×), as 9,13′cis (1×), and as 13-cis (1×).2 Note that the ratio of cis over all-trans Cars more or less matches the ratio of the fast over the slow decay component. Why would a cis Car be a better donor of its S1 energy than an all-trans Car? Though the C2-symmetry is broken, the cis S0 f S1 transition is still forbidden because of the alternating single and double bond structure. However, the coupling between the Car S0 f S1 transition and the Chl transition is Coulombic and depends on the mutual configuration rather than on the oscillator strength of the transitions. The twisted configuration may give rise to important contributions of the higher-order terms in the multipole expansion. In other words, the cis Car might be better positioned “around” the Chl to facilitate the energy-transfer process. The presence of nearby red Chls or Cars adopting a cis configuration or both as reasons for a transferring Car S1 pool in PSI could explain why EET from the (relaxed) Car S1 state to the Chls is absent in the PSII core, which does not comprise red Chls and most likely lacks cis β-carotenes.23 However, as mentioned above, the effect of red Chls on the spectral overlap cannot be large and both suggestions are difficult to support with our experimental data. Therefore, we conclude that the S1 transfer associated with the fast-decaying Car S1 pool in the PSI core from S. elongatus is due to favorable π-π stacking of several β-carotenes (cis or all-trans or both) with nearby Chls. Acknowledgment. We thank Eberhard Schlodder for providing us with the samples. This research was supported by The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) via the Dutch Foundation for Earth and Life Sciences (ALW). References and Notes (1) van Grondelle, R.; Dekker, J. P.; Gillbro, T.; Sundström, V. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1994, 1187, 1-65. (2) Jordan, P.; Fromme, P.; Witt, H.-T.; Klukas, O.; Saenger, W.; Krauss, N. Nature 2001, 411, 909-917. (3) Rhee, K.-H.; Morris, E. P.; Barber, J.; Kühlbrandt, W. Nature 1998, 396, 283-286. (4) Gobets, B.; van Grondelle, R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1507, 80-99. (5) Pålsson, L. O.; Dekker, J. P.; Schlodder, E.; Monshouwer, R.; van Grondelle, R. Photosynth. Res. 1996, 48, 239-246. (6) Byrdin, M.; Rimke, I.; Schlodder, E.; Stehlik, D.; Roelofs, T. A. Biophys. J. 2000, 79, 992-1007. (7) Zazubovich, V.; Matsuzaki, S.; Johnson, T. W.; Hayes, J. M.; Chitnis, P. R.; Small, G. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 275, 47-59. (8) Sener, M. K.; Lu, D.; Ritz, T.; Park, S.; Fromme, P.; Schulten, K. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 7948-7960. (9) Damjanovic, A.; Vaswani, H. M.; Fromme, P.; Fleming, G. R. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 10251-10262. (10) Gobets, B.; van Stokkum, I. H. M.; van Mourik, F.; Dekker, J. P.; van Grondelle, R. Biophys. J., submitted for publication. (11) Frank, H. A.; Cogdell, R. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 1996, 63, 257264. (12) Haley, J. L.; Fitch, A. N.; Goyal, R.; Lambert, C.; Truscott, T. G.; Chacon, J. N.; Stirling, D.; Schalch, W. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992, 17, 1175-1176. de Weerd et al. (13) Andersson, P. O.; Bachilo, S. M.; Chen, R. L.; Gillbro, T. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 16199-16209. (14) Onaka, K.; Fujii, R.; Nagae, H.; Kuki, M.; Koyama, Y.; Watanabe, Y. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 315, 75-81. (15) Macpherson, A. N.; Gillbro, T. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 50495058. (16) Förster, Th. In Modern quantum chemistry; Sinanoglu, O., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, 1965; Part II, pp 93-137. (17) Krueger, B. P.; Scholes, G. D.; Jimenez, R.; Fleming, G. R. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 2284-2292. (18) Krueger, B. P.; Scholes, G. D.; Fleming, G. R. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 5378-5386. (19) Damjanovic, A.; Ritz, T.; Schulten, K. Phys. ReV. E 1999, 59, 3293-3311. (20) Hsu, C. P.; Walla, P. J.; Head-Gordon, M.; Fleming, G. R. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 11016-11025. (21) van Dorssen, R. J.; Breton, J.; Plijter, J. J.; Satoh, K.; van Gorkom, H. J.; Amesz, J. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1987, 893, 267-274. (22) Kwa, S. L. S.; Newell, W. R.; van Grondelle, R.; Dekker, J. P. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1992, 1099, 193-202. (23) de Weerd, F. L.; Dekker, J. P.; van Grondelle, R. J. Phys. Chem. B, in press. (24) van der Lee, J.; Bald, D.; Kwa, S. L. S.; van Grondelle, R.; Rögner, M.; Dekker, J. P. Photosynth. Res. 1993, 35, 311-321. (25) Kennis, J. T. M.; Gobets, B.; van Stokkum, I. H. M.; Dekker, J. P.; van Grondelle, R.; Fleming, G. R. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 44854494. (26) Fromme, P.; Witt, H.-T. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1365, 175184. (27) Gradinaru, C. C.; van Stokkum, I. H. M.; Pascal, A. A.; van Grondelle, R.; van Amerongen, H. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 93309342. (28) van Stokkum, I. H. M.; Scherer, T.; Brouwer, A. M.; Verhoeven, J. W. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 852-866. (29) Pålsson, L. O.; Flemming, C.; Gobets, B.; van Grondelle, R.; Dekker, J. P.; Schlodder, E. Biophys. J. 1998, 74, 2611-2622. (30) Savikhin, S.; Xu, W.; Chitnis, P. R.; Struve, W. S. Biophys. J. 2000, 79, 1573-1586. (31) Gobets, B.; van Stokkum, I. H. M.; Rögner, M.; Kruip, J.; Schlodder, E.; Karapetyan, N. V.; Dekker, J. P.; van Grondelle, R. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 407-424. (32) Brettel, K.; Leibl, W. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1507, 100114. (33) Käss, J.; Fromme, P.; Witt, H.-T.; Lubitz, W. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 1225-1239. (34) Donovan, B.; Walker, L. A.; Yocum, C. F.; Sension, R. J. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 1945-1949. (35) Gradinaru, C. C.; Kennis, J. T. M.; Papagiannakis, E.; van Stokkum, I. H. M.; Cogdell, R. J.; Fleming, G. R.; Niederman, R. A.; van Grondelle, R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001, 98, 2364-2369. (36) Papagiannakis, E.; Kennis, J. T. M.; van Stokkum, I. H. M.; Cogdell, R. J.; van Grondelle, R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 60176022. (37) Billsten, H. H.; Zigmantas, D.; Sundström, V.; Polı́vka, T. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 355, 465-470. (38) Zhang, J. P.; Inaba, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Koyama, Y. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 331, 154-162. (39) de Weerd, F. L.; van Stokkum, I. H. M.; van Grondelle, R. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 354, 38-43. (40) van Stokkum, I. H. M.; Beekman, L. M. P.; Jones, M. R.; van Brederode, M. E.; van Grondelle, R. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 11360-11368. (41) Kennis, J. T. M.; Holt, N. E.; Schlodder, E.; Dekker, J. P.; van Grondelle, R.; Fleming, G. R., manuscript in preparation. (42) Renge, I.; van Grondelle, R.; Dekker, J. P. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 1996, 96, 109-121. (43) Hashimoto, H.; Koyama, Y.; Hirata, Y.; Mataga, N. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 3072-3076.

![Solution to Test #4 ECE 315 F02 [ ] [ ]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/011925609_1-1dc8aec0de0e59a19c055b4c6e74580e-300x300.png)