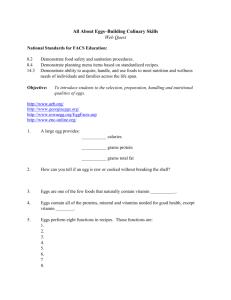

E

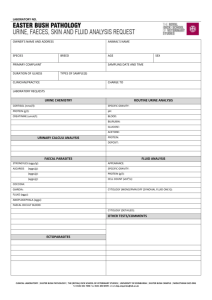

advertisement