Document 13955796

advertisement

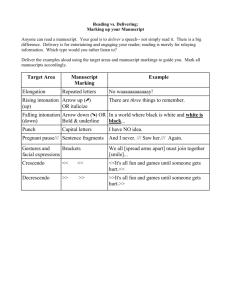

PTLC2005 Juhani Toivanen Stylized intonation in Finnish English second language speech: a semantic and acoustic study:1 Stylized intonation in Finnish English second language speech: a semantic and acoustic study Juhani Toivanen Academy of Finland and MediaTeam, University of Oulu 1 Introduction In spoken English produced by native speakers, stylized intonation (stylization) involves the use of levels rather than glides. The typical pattern involves stepping down from a steady level pitch to another level pitch. Stylized intonation contours are usually placed at mid-pitch or at high pitch in the speaker’s voice range. Stylized intonation is used in spoken English with such speech functions as calling, warning, reminding, etc. Basically, stylized intonation conveys the idea that what is communicated is in some way a predictable or routine (or ritualistic) message. Thus, with stylized intonation, it is assumed that a part of the message is implicitly available in the context. Stylized intonation contours often occur in “domestic” situations where the message is part of people’s everyday activities. The following expressions, for example, might be accompanied by stylized intonation in everyday parlance: /food’s ready!/, /anyone there?/, and /hi grandma!/. According to Roach (1991: 140), stylized intonation typically accompanies speech events saying something “routine”, “uninteresting” or “boring”. Brazil (1997: 136) argues that “certain language formulae which accompany oft-repeated business” are often produced with stylization (or with the level “o tone”): the level “o tone” indicates that the words are “a routine performance” whose “appropriateness” to the speakers’ present situation is recognized by both speakers. It should be stressed that stylization is by no means limited to the general category of “calling” or “oft-repeated business”; as Cruttenden (1997: 120) points out, stylization often co-occurs with “teasing” in a creative way. Utterances meant to sound playful or slightly teasing may involve stylization: /boring!/, /you’ve got a hole in your tights!/, etc. Stylization is thus a productive category in spoken English: it is possible to produce long utterances with stylized patterns with no restrictions on the semantic/pragmatic content of the message (as long as the “routine-like”, “teasing” or “playful” overtone of the message is intended, or if the message is meant to ritualistically reflect the common ground between speaker and hearer). Similarly, Brazil (1997: 137-138) points out that long stretches of speech, if they mark off a “piece of received wisdom” or a “definitive expression of a truth”, are uttered with stylization; such intonation patterns are, according to Brazil, very common in lectures and teaching in general. 2 Speech data There is a considerable literature on English intonation representing both theoretical and pedagogical viewpoints: the descriptive approach may be based on the traditional nuclear tone framework or the more recent ToBI model. It is fair to say that the acoustic and semantic/pragmatic aspects of (British) English intonation are understood quite well. In contrast, the literature on the English intonation of Finns is very limited: the most systematic and recent treatment can be found in Toivanen (2001). Other dissertations on the topic date back to the 1960’s (e.g. Hirvonen 1967). However, even the most recent source (Toivanen 2001) is based on completely non-spontaneous speech data, the PTLC2005 Juhani Toivanen Stylized intonation in Finnish English second language speech: a semantic and acoustic study:2 experimental design involving a dialogue reading exercise from a phonetics text book. In Toivanen (2001), a detailed acoustic and semantic analysis is carried out on the major tones (fall, rise, rise-fall, fall-rise), while very little attention is paid to stylization. It can be argued, then, that stylization is the least well-known tone type as far as Finnish English intonation is concerned. It is plausible, however, that Finnish speakers of English systematically use stylization in their English speech, but that the non-native way of stylizing is (semantically and/or phonetically) different from native speaker conventions. As for the present investigation, the emphasis was put on spontaneous (or nearly spontaneous) speech data, and the aim was to compare systematically Finnish English intonation and native English intonation from the viewpoint of stylization. The speech data in this project was collected as part of English conversation class in a Finnish college (the speech data is being used for a number of research purposes in addition to the present investigation). The test subjects (six females) discussed a topic of their choice (which turned out to be the recent international recognition of Finnish pop music). The speakers’ speech data was recorded directly to hard disk (44.1 kHz, 16 bit) using a high-quality microphone; the discussion and recording took place in a sound-treated room in Oral Communication Skills class. The total duration of the discussion (including pauses, asides in Finnish, short interruptions, etc.) was 45 minutes (i.e. half of a doublelesson). It must be pointed out that the conversation touched upon Finnish films and actors/actresses and other celebrities, in addition to the agreed-on topic (pop music). The recorded speech data was transcribed orthographically without punctuation; capital letters were used with proper names. Six native speakers of British English (female exchange students (not studying linguistics or phonetics) were asked to act out the transcripts in a group session to simulate conversational English; technically, the data collection procedure was carried out as with the Finnish English data set. The British informants took the roles of the original speakers and read out exactly the same lexical material (excluding the remarks made in Finnish). The British informants could divide the material into speech units (TCU’s) of they choice (see the next section), and they could, of course, produce each unit with any intonation pattern they thought appropriate. 3 Analysis The prosodic analysis was carried out instrumentally/acoustically with CSL (Computerized Speech Laboratory), and the prosodic unit of interest in the speech data was the turn constructional unit (TCU). In the analysis, it was assumed that each turn consisted of at least one TCU, and that each TCU contained a transition relevant place. The TCU’s were identified with prosodic and syntactic criteria: the most obvious criterion was the presence of pause (preceded by a coherent tone unit). In effect, in the analysis, the TCU’s were defined as tone units, and they contained, by definition, tonics; the TCU’s were sometimes (but not nearly always) also pause-defined units. It was assumed that there was a transition relevant place after each TCU in the turn: after a coherent nuclear tone and possible final syllable lengthening (sometimes followed by a pause), the next speaker could select herself. Theoretically, a tone unit is not always a TCU as it might be difficult for the next speaker to treat an adverbial clause in initial position containing a fall-rise pattern, for example, as a TCU: the next speaker would probably feel that this clause is necessarily followed by the main clause, so there cannot be a transition relevant place between the clauses. Theoretical considerations aside, the TCU was in this analysis an operational unit equated with a tone unit. PTLC2005 Juhani Toivanen Stylized intonation in Finnish English second language speech: a semantic and acoustic study:3 Intonation was coded using the Brazil framework (1997) involving “tone”, “key” and “termination”. The possible intonation contours were the following: r (fall-rise), r+ (rise), p (fall), p+ (rise-fall), and o (level tone). So far, the Brazilian type of intonation analysis has been carried out for tone unit segmentation and tone; features of key and termination are yet to be analyzed in detail. The recorded speech data produced by the informants was auditorily transcribed by the present author: the speech was divided into tone units (TCU’s), and tone choice was determined for each unit. The f0 contour data produced by the acoustic analysis helped the investigation when the auditory impression of tone choice was unclear. The analysis was carried out in the same way for both sets of speech data (the original conversational data and the simulated data produced by the native speakers). In addition to the (auditory) intonation analysis, the average length of a TCU containing stylization was calculated (in syllables). Furthermore, the average pitch range (f0 range) was determined for the stylized contours: for each stylized contour, the f0 maximum and the f0 minimum were determined, and the difference was expressed on the logarithmic semitone scale (ST). 4 Results Table 1 shows the distribution of tones for both sets of speech data; note that the absolute number of tones also indicates the absolute number of TCU’s in this analysis. Tone choice Data set Non-native speakers: 1456 tones Native speakers: 1227 tones r fall-rise r+ rise p fall p+ rise-fall o stylization 5.0 % 73 15.1 % 220 70.3 % 1024 6.6 % 96 3.0 % 44 12.3 % 151 25.1 % 308 52.3 % 642 7.5 % 92 2.8 % 34 Table 1. Tone choice in the speech data: non-native and native speakers. Stylized intonation contours made up 3.0 % of all tone types in the non-native speech data and 2.8 % in the native speech data; the difference in the absolute number was not significant (x2=0.15, df=1, p>0.05). In the native data, the average length of a TCU containing stylized intonation was 5.7 syllables, while in the Finnish data it was 2.3 syllables. The difference was highly significant (t=3.9, df=22.0, p<0.001). The acoustic analysis revealed that the native speakers used a narrower pitch range with stylization than the Finns (1.2 ST vs. 1.6 ST); the difference was significant (t=3.2, df=18.3, p<0.01). From a qualitative viewpoint, it can be observed that, with the Finns, the stylized contours were practically always limited to short utterances basically representing backchannel communication, such as /yes/, /I see/, /OK/, etc., whereas the English speakers mostly used stylization in considerably longer utterances (without any restrictions on the lexical content) to signal that a part of the message was implicitly available in the context. 5 Discussion and conclusion PTLC2005 Juhani Toivanen Stylized intonation in Finnish English second language speech: a semantic and acoustic study:4 First of all, it should be pointed out that any conclusions must be tentative as the native speech data represented simulated speech material. We cannot be sure that the native speakers would have used a similar pattern of stylization (acoustically and/or semantically/pragmatically) had the speech situation been natural. This said, however, a number of conclusions seem possible. Firstly, the results suggest that the Finns used stylized intonation rather restrictively in comparison with native English standards: the tone was used mainly in formulaic utterances or ready-made chunks (often representing straightforward back-channel communication). The native speakers, in contrast, used stylization in a more productive way. Typical examples are the following TCU’s, in which most of the native-speaker informants, unlike the Finns, used stylization: /all over the charts everywhere now/, /over and over again/, and /who wants to hear that all the time/. In these examples, in the discussion on pop music, the common ground aspect of stylization is obvious. The more productive use of stylization on the part of the native speakers naturally reflects the observed difference in the average length of stylizationTCU’s between the two data sets. The results also suggest that there may be potentially relevant differences between the realizations of the tones: the native speakers used a significantly narrower pitch range with stylization. This observation is interesting as the existing evidence points in the opposite direction: with rising intonation, Finnish speakers of English use significantly narrower pitch ranges than native speakers of English (Hirvonen 1967; Toivanen 2001). Maybe stylization is, however, a different kind of challenge for the non-native speaker: in contrast with the high-rise, for example, the most important thing with stylization is to be able to produce a pitch range which is, in actual fact, narrow enough (so that the tone can be interpreted as stylization instead of a glide). The pedagogical implication is that Finnish learners/speakers of English should be made aware of the full meaning potential of stylized intonation; some instruction in the phonetic form of this intonation pattern may also be useful. These needs exist despite the fact that Finnish speakers of English probably have an overall idea of the general form and function of this tone in spoken English. 6 References Brazil, David (1997) The Communicative Value of Intonation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cruttenden, Alan (1997) Intonation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hirvonen, Pekka (1967) On the problems met by Finnish students in learning the rising interrogative intonation in English. Publications of the Department of Phonetics: University of Turku. Roach, Peter (1991) English Phonetics and Phonology: a practical course. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Toivanen, Juhani (2001) Perspectives on Intonation: English, Finnish and English Spoken by Finnish. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.