Document 13910660

advertisement

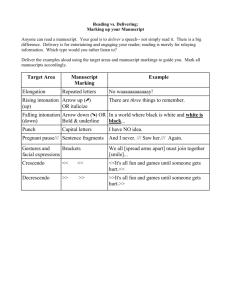

Turn-Taking and Coordination in Human-Machine Interaction: Papers from the 2015 AAAI Spring Symposium The Sound Makes the Greeting: Interpersonal Functions of Intonation in Human-Robot Interaction Maria Ibh Crone Aarestrup, Lars C. Jensen, and Kerstin Fischer Institute for Design and Communication, University of Southern Denmark appreciate robots that employ different intonation contours in greetings in human-robot interaction and which kinds of intonation contours people prefer. Abstract In this paper, we study the effects of different ways of producing greetings in human-robot interaction. We first generated computer utterances of verbal greetings, whose intonation contours, we then manipulated using Praat. Each utterance was matched with a video of a robot waving a greeting at the observer. Altogether, the experiment uses two lexical items (hello vs. hi), three robots and four different intonation contours. The videos were distributed over different questionnaires so that each participant only got to see each robot once. The results reveal that native speakers of English rate the robots significantly different concerning friendliness, assertiveness, and engagement depending on the intonation contours. However, these effects differ for the different lexical items, and the apparently non-conventional hi with rising intonation contour was in fact rated as most engaging. 2 Previous Work Previous work concerns greetings in human communication, the functions of intonation in greetings, and the role of greetings in human-robot interaction. 2.1 Human Greetings In interactions between humans, greetings are important because they often have consequences for the interaction that follows and they fulfill several functions. Krivonos and Knapp (1975) describe three different functions of greetings: First, greetings are a means of signaling accessibility to other people. Second, greetings can reveal information about the exact state of the relationship between two people, depending on which kind of greeting people engage in and how well they know each other. Third, they also have a maintaining function, regulating interpersonal relationships; for instance, one would want to design a greeting for a close friend differently than for a new colleague, and for that close friend differently whether it’s been a year or two hours since our last encounter (PilletShore 2012). Kendon (1990) distinguishes between three stages of greetings: the distance salutation, the approach, and the close salutation. These stages might be accompanied by different nonverbal acts such as head tosses, head lowers, nodding and waves. In this paper, we concentrate on close salutations. 1 Introduction Greetings are social exchanges (Kendon 1990) and involve both nonverbal, such as proxemics (e.g. Kendon 1990), and verbal features. Verbal features comprise the length, height and loudness of an utterance as well as its realization in terms of speech melody, or intonation contour, which speakers make use of when designing greetings for their respective addressees (Pillet-Shore 2012). Several studies in human-robot interaction have focused on nonverbal properties of greetings, such as proximity, gesture and facial expression (e.g. Heenan et al 2013, Trovato et al. 2013, and Scheeff et al. 2002). In contrast, this paper focuses on verbal greetings in human-robot interaction, more precisely on the use of different intonation contours to fulfill interpersonal functions, for instance regarding formality, politeness and friendliness in greetings. It is examined how people perceive and 2.2 Greetings and Intonation Contours Copyright © 2015, Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved. People design their greetings prosodically, adapting the intonation contours of the greetings to the addressee, and 67 by doing this, people express stance toward their addressee and their current relationship (Pillet-Shore 2012). On the one hand, there are suggestions about the functions of intonation contours in general. For instance, Tench (1996:105) suggests that thus different predictions regarding the effects of speech melody on the perception of the speaker. In sum, intonation is an important feature of spoken interaction to convey both linguistic and pragmatic meanings. In the case of greetings, intonation contours have been suggested to indicate, for instance, formality or informality and interest in the addressee, yet the exact function is unclear. - a fall indicates the speaker’s dominance in knowing and telling something, in telling someone what to do, and in expressing their own feelings; - a rise indicate a speaker’s deference to the addressee’s knowledge, their right to decide, and their feelings. 2.3 Greetings and Intonation Contours Several studies in human-robot interaction have addressed how robots should initiate conversation. Many have looked at nonverbal behavior including proximity (e.g. Heenan et al. 2013 and Satake et al. 2009), gestures (e.g. Trovato et al. 2013), and facial expressions (e.g. Breazeal & Scassellati 1999 and Scheeff et al. 2002). Cockley et al. (2005) argue that greetings should be used in human-robot interaction to foster long-term interactions. The greetings should make the robot friendly and engaging and help shape expectations for humans on how to communicate with robots. Furthermore, Pitsch et al. (2009) demonstrate that the first 5 seconds matter in human-robot interaction and Bar et al. (2006) suggest that first impressions can be formed already after the first 39ms; thus, verbal greetings may have an effect on creating certain robot personalities. However, other authors suggest other functions for rising and falling intonation contours. For instance, Lakoff (1972) suggests that rising intonation contours are associated with politeness and insecurity. In contrast, Fishman (1978) holds that a rising intonation contour is associated with more involvement of, and openness to, the addressee, whereas a falling intonation contour is associated with more factual information and less involvement of the addressee. Moreover, utterances do not necessarily only have either a falling or rising nuclear tone, but they can also exhibit a so-called fall/rise intonation contour (Wells 2006); a fall/rise contour has been suggested to attract attention to what is said (Tench 1996). Using ethnomethodological conversation analysis (Sacks et al. 1974), some authors have also identified interactional effects of such intonation contours. For instance, Gardner (2001) analyzes the functions of intonation contours of the backchannel mm and finds that a falling speech melody signals the end of a topic whereas a rising melody elicits further information from the communication partner. These studies suggest that a greeting with rising intonation should be perceived as more open and engaging than a greeting with falling intonation contour. On the other hand, some studies make concrete predictions regarding intonation contours in greetings. For instance, Wells (2006) argues that there are default tones for the greetings hello and hi. The greeting hello can either have a falling or a rising intonation contour. The falling intonation contour is the default tone and is assumed to be more formal. The rising intonation contour makes the greeting hello more personal and expresses an added interest in the addressee. According to Wells (2006), the greeting hi in English can only take a falling intonation contour. In contrast, Pillet-Shore (2012), who uses as conversation analytic approach, finds only either slightly falling or falling-to-low intonation contours in her data. She argues that longer fall-to-low greetings are used with friends while shorter greetings with slight falls are used for strangers. These two studies, Wells and Pillet-Shore, make 3 Method and Procedure Figure 1: ‘Hello’ with falling and rising contour We created videos of three different robots greeting the observer using different intonation contours as stimuli by matching video scenes of robots waving at the observer with one of two utterances in order to study the effect of different greetings and their intonation contours. Thus, the same robot would be heard in one condition with one intonation contour and in the second condition with another. These videos were then played to participants in a questionnaire study. Participants were asked about their impressions of each robot based on its greeting, which meant that they could only see each robot once and three in total. The effects of the intonation contours were thus tested in pairs (see the section on stimuli creation below). 68 3.3 Analysis The analysis of the results of the questionnaire was carried out by means of a one-way ANOVA using the statistical software package SPSS. 4 Results In total, 200 participants completed the questionnaire on Crowdflower, yet we eliminated the data of those participants who completed the questionnaire faster than the total length of the videos in the questionnaire, leaving us with 120 participants. The majority of these participants are non-native speakers of English and between 20 and 40 years old. The linguistic background of this group is very heterogeneous; the participants report more than 30 different languages as their native languages. Of the 120 participants, 24 participants are native speakers of English. The statistical analysis shows that there are no significant results for the conditions for the non-native speakers of English. However, if we consider only the evaluations made by the group of native speakers of English, the results are very different: First, concerning the Care-O-bot, when asked to rate the robot that uses hello with a falling intonation contour, the robot is rated significantly more friendly (M = 2.83, SD = 0,91) than the robot that uses the rising intonation contour (M = 3.67. SD = 1.03), [F(1,28) = 5.46, p = .027]. Furthermore, the Care-O-bot that uses hello with a falling intonation contour is rated significantly more certain (M = 3.00, SD = 1.04) than the Care-O-bot that uses the rising intonation contour (M = 3.89, SD = 1.23), [F(1,28) = 5.35, p = .028]. Moreover, the Care-O-bot that uses hello with a falling intonation contour is rated significantly better at getting attention (M = 3.00, SD = 1.41) than the Care-O-bot that uses the rising intonation contour (M = 4.00, SD = 0.91) [F(1,28) = 5.60, p = .025]. Second, we find that concerning the Nao that uses hello with a falling-rising intonation contour is rated significantly more engaging (M = 2.64, SD = 0.92) than the Nao that uses hello with the flat intonation contour (M = 3.44, SD = 0.98) [F(1,27) = 4.82, p = .037]. Third, the Robosapien that uses hi with a rising intonation contour (M = 2,36, SD = 1,21) is rated more engaging on a near-significant level than the Robosapien that uses hi with the falling intonation contour (M = 3.17. SD = 1.04) [F(1,27) = 4.40, p = .069]. Further, the robot that uses hi with a rising intonation contour (M = 2.27, SD = 1.19) is rated as significantly better at getting attention in a positive way than the robot that uses the falling intonation contour (M = 3.39. SD = 1.20) [F(1,27) = 5.97, p = .021]. Figure 2: ‘Hello’ with fall/rise and flat intonation contour. 3.1 Stimuli Each greeting (hello and hi) was first produced using a text-to-speech synthesizer and then imported into Praat, where the intonation contours were manually manipulated to create the chosen intonation contours for each greeting. We then matched each greeting with a video of a robot waving a greeting at the observer. The robots used are: Care-O-bot, developed by Frauenhofer IPA; the video of the Care-O-bot was matched with hello with a falling and with hello with a rising intonation contour. Nao, developed by Aldebaran Robotics; the video of the Nao was matched with hello with a fall-rise and with hello with a flat intonation contour. Robosapien, developed by WowWee; the video of the Robosapien was matched with hi with a falling and with hi with a rising intonation contour. Figure 3: ‘Hi’ with a falling and rising intonation contour 3.2 Questionnaire We used a self-administered online questionnaire using the distribution platform Crowdflower. The first part of the questionnaire consists of demographic questions. In the second part, participants were asked to rate the robot they have seen in the video on a semantic differential scale from 1-7 regarding the following aspects: formality, politeness, friendliness, certainty, and engagement. These questions concern the functions hypothesized to hold for the intonation contours suggested in the literature. The videos were distributed across different questionnaires so that each participant only got to see each robot once. 69 unfolding (see Pitsch et al. 2009). The effects identified occurred with all three robots, suggesting that the findings may apply to social robots in general. The details of linguistic production should thus be taken into account in robot utterance design. 5 Discussion First, we find that the different intonation contours do not influence the interpretation of the robots by nonnative speakers of English. This is understandable since the intonation systems differ considerably between languages, yet they are hardly ever covered in language teaching. Non-native speakers thus seem to simply ignore this cue in their evaluation of the greeting. Second, we observed that native speakers of English rate the robots significantly different depending on the intonation contours used. The robot that uses hello with a falling intonation contour was rated as more friendly, more certain, and better at getting attention. This is in line with the literature on the effects of falling versus rising intonation in general, where falling intonation is associated with assertiveness. Moreover, people preferred the robot that uses a fall/rise intonation contour over a robot that uses a flat intonation contour in terms of engagement. This is in accordance with PilletShore (2012) since a falling-rising intonation contour signals more interactional effort than a flat contour and should thus signal more engagement. Finally, the robot that uses hi with a rising intonation contour was rated as more engaging and as better at getting attention. Particularly interesting is the finding that hello with rising contour is rated as less attention getting than hi with rising intonation, which corresponds to Wells’ observation that hi is not conventionally used with rising intonation. Thus, the unusual combination of lexical item and intonation contour creates an attention-getting effect. The results have implications for the design of robot greetings such that at least for native speakers of the respective language intonation seems to provide important social cues. A possible limitation of this study is the use of Crowdflower to elicit responses; online questionnaires may simply not be reliable enough. Another possible problem is that the results have been obtained using video interactions and thus may not be applicable to real interactions with ‘live’ robots. However, the results obtained here are in line with recent results by Fischer et al. (2014), where similar effects were observed for robots with falling and rising intonation in beep sequences. Thus, we believe that we can safely assume that the results also apply to real-life humanrobot interactions. To conclude, while much previous work on human-robot interaction has concentrated on nonverbal aspects of human-robot interaction, our results suggest that the highly multifunctional, social system of verbal communication needs to be adjusted carefully to interactions with robots in order to produce the desired effects. Our results show that for native speakers of English, intonation contours carry meanings that influence the first impression the robot makes, which in turn may be defining for the interaction References Bar,M., Neta, M., Linz, H. 2006. Very first impressions. Emotion 6(2), 269-278. Doi:10.137/1528-3542.6.2.269 Breazeal, C., & Scassellati, B. 1999. How to build robots that make friends and influence people. Intelligent Robots and Systems, IROS'99. Fischer, K., Jensen, L.C. and Bodenhagen, L. 2014. To Beep or not to Beep Is not the Whole Question. International Conference on Social Robotics’14, Sydney. Fishman, P. 1978. Interaction: The work women do. Social Problems 25, pp. 397-406. Gardner, R. 2001. When Listerners talk. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Gardner, R., Lambert, W. 1972. Attitudes and motivation in a second-language learning. Rowley Massachusetts: Newsbury House Publishers. Heenan, B., Greenberg, S., Aghelmanesh, S., & Shalin, E. 2013. Designing Social Greetings and Proxemic in Human Robot Interaction. Designing Interactive Systems DIS'14, 855-864. Kendon, A. 1990. Conducting interaction - patterns of behavior in focused encounters. Cambridge University Press. Krivonos, P.D., Knapp, M.L. 1957. Initiating Communication: What Do You Say When You Say Hello? Central States Speech Journal 26(2), 115-125. Lakoff, R. 1972. Language and Women’s Place. New York. Harper & Row. Pillet-Shore, D. 2012. Greeting: Displaying Stance Through Prosodic Recipient Design. Research on language and social interaction 45 (4), 375-398. Pitsch, K., Kuzuoka, H., Suzuki, Y., Süssenbach, L., Luff, P & Heath, C. 2009. ‘The first five seconds’: Contingent stepwise entry into an interaction as a means to secure sustained engagement in HRI. The 18th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Toyama, 985-991. Satake, S., Kanda, T., Glas, D., Imai, M., Ishiguro, H., & Hagita, N. 2009. How to approach humans? Strategies for social robots to initiate interaction. Proc. of the Human-Robot Interaction Conference HRI’09. Scheeff, M., Pinto, J., Rahardja, K., Snibbe, S., & Tow, R. 2002. Experiences with Sparky, a social robot. Socially Intelligent Agents (pp. 173-180): Springer. Tench, P. 1996. The Intonation Systems of English. London: Cassell. Trovato, G., Zecca, M., Sessa., S., Jamone, L., Ham, J., Hashimoto, K., & Takanishi, A. 2013. Towards culture-specific robot customisation: A study on greeting interaction with Egyptians. RO-MAN’13, 447-452. Wells, J. C. 2006. English intonation: an introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 70