Document 13893853

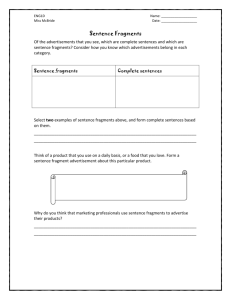

advertisement