Health Care Alert Disposing of Hazardous Pharmaceutical Wastes: It’s The Problem

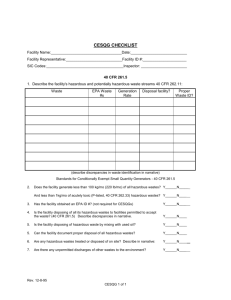

advertisement

Health Care Alert December 2008 Authors: Raymond P. Pepe +1.717.231.5988 raymond.pepe@klgates.com Patricia Shea +1.717.231.5870 patricia.shea@klgates.com Jessica Leigh Wray +1.717.231.4815 leigh.wray@klgates.com K&L Gates comprises approximately 1,700 lawyers in 28 offices located in North America, Europe and Asia, and represents capital markets participants, entrepreneurs, growth and middle market companies, leading FORTUNE 100 and FTSE 100 global corporations and public sector entities. For more information, visit www.klgates.com. www.klgates.com Disposing of Hazardous Pharmaceutical Wastes: It’s Not Just for Hospitals Anymore The Problem The EPA is stepping up its inspections of healthcare facilities to ensure that they are complying with regulations governing the disposal of hazardous pharmaceutical wastes. Indeed, recent EPA inspections of hospitals in Regions 1, 2 and 4 have produced compliance orders and fines ranging from $40,000 to more than $250,000 for violations of hazardous waste management requirements. The EPA has also notified many other hospitals that they are targets of future EPA inspections, and given the breadth of the federal regulations, other types of healthcare facilities are left to wonder who is going to be next. The EPA, however, wants to make it “easier” for hospitals and other healthcare facilities to comply with regulations governing hazardous pharmaceutical waste disposal. The EPA’s “solution” is a proposal published in the December 2, 2008, Federal Register for healthcare facilities, and others, to optionally classify hazardous pharmaceutical waste as “universal wastes.” This proposal would apply not only to hospitals, but also to most other types of healthcare facilities, including retail pharmacies, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and physician, dentist and veterinary offices. Healthcare facilities should regard EPA’s proposal as a clear indication that the EPA and state environmental regulators will be expanding current efforts to ensure compliance with pharmaceutical waste management requirements beyond hospitals to other types of healthcare facilities. Owners and operators of all types of healthcare facilities therefore have a stake in the EPA’s proposal and should review it and submit comments as warranted. Perhaps more importantly, healthcare facilities should also carefully evaluate whether their current operations comply with existing waste management regulations so that they do not become the next recipients of the EPA’s fines. This Alert describes generally how hazardous pharmaceutical wastes are currently regulated and how the EPA’s proposal would modify that regulatory structure. The Alert discusses whether the EPA’s proposal makes sense for healthcare facilities and explains how healthcare facilities can, and perhaps should, submit comments to the EPA’s proposal. Current Regulation of Hazardous Pharmaceutical Wastes How Is Hazardous Pharmaceutical Waste Generated? All healthcare facilities – not just hospitals – have the potential to become generators of hazardous pharmaceutical waste if they collect or receive returns of unused prescription or over-the-counter medications, generate residues through the compounding of prescriptions, dispose of medications that are spilled or otherwise contaminated, or dispose of out-of-date medications other than through their return to reverse distributors or manufacturers for credit. In these circumstances, Health Care Alert the healthcare facilities must evaluate whether the pharmaceutical products contain as their sole active ingredient chemical products which (1) could potentially be lethal if administered in oral doses of 50 mg/kg or less (i.e., “acutely hazardous” “P” class waste), (2) have been specifically designated by the EPA as “toxic” (i.e., “U” class wastes); or (3) display characteristics of ignitability, corrosivity, reactivity or toxicity as determined by testing or other analysis. Hazardous waste generators are classified into one of three categories depending on the total amounts of all types of hazardous waste generated at a particular site in any month, as follows: Large Quantity Generators (“LQGs”) Small Quantity Generators (SQGs”) Conditionally Exempt Small Quantity Generators (“CESQGs”) produce 1000 kg or more of hazardous waste per month (approximately 2,200 lbs), or greater than 1 kg of acutely hazardous waste per month (approximately 2.2 lbs) produce between 100 kg (approximately 220 lbs) and 1,000 kg of hazardous waste per month and 1 kg or less of acutely hazardous waste per month produce 100 kg or less per month of hazardous waste, or 1 kg or less per month of acutely hazardous waste In applying these quantity limits, generators must include not only pharmaceutical wastes, but also containers used for storage of hazardous pharmaceutical wastes, personal protective clothing contaminated with such wastes, or other materials with which hazardous waste are mixed, including debris contaminated by spills, when making their calculations. Most facilities that generate hazardous pharmaceutical wastes are classified as SQGs or CESQGs. However, classifications may change from month-to-month, especially based upon the production of more than one kilogram of any acute hazardous wastes. What must generators do to dispose of the hazardous pharmaceutical wastes? LQGs and SQGs are required to manage, store and arrange for the processing or disposal of hazardous pharmaceutical wastes pursuant to federal and state hazardous wastes management requirements that obligate them to (1) register with the EPA as hazardous waste generators; (2) either limit the amounts of hazardous waste stored on-site and the length of time waste is accumulated prior to offsite management and disposal, or obtain hazardous waste storage permits; (3) either arrange for the transportation of waste for processing or disposal at facilities permitted to process or dispose of hazardous waste, or obtain permits for the on-site processing or disposal; (4) comply with hazardous waste transportation requirements pertaining to packaging and manifesting requirements; (5) comply with detailed requirements regarding containers and tanks used for the on-site storage of hazardous waste; (6) comply with hazardous waste preparedness and prevention plan and emergency management requirements; (7) certify the completion of best efforts to minimize the production of hazardous wastes; and (8) maintain detailed records regarding the generation and management of hazardous wastes. CESQGs have more flexibility in managing hazardous wastes. For example, CESQGs are not required to register with the EPA and do not have to comply with manifesting requirements. CESQGs may also use certain types of qualified municipal or non-hazardous industrial waste disposal facilities and sewage systems connected to publicly-owned wastewater treatment facilities. Like LQGs and SQGs, however, CESQGs must determine whether wastes are hazardous. CESQGs are also subject to more stringent limitations than other generators regarding the amounts of hazardous waste that may be stored prior to processing or disposal and the period of time that it may be stored, unless a December 2008 | 2 Health Care Alert CESQG applies for and obtains a hazardous waste storage permit. Do the states also regulate this waste? The federal hazardous waste management program establishes minimum standards that apply in all states, but states are free to impose additional, more stringent requirements. For example, in some jurisidictions, including Pennsylvania, CESQGs are prohibited from disposing of any hazardous wastes in municipal or residual waste management facilities. States are also not required to adopt the EPA’s more flexible universal waste management standards, and to date only a limited number of states have done so. The EPA’s compliance program and proposed expansion of the universal waste rule may spur many states into re-evaluating their requirements for the management of pharmaceutical wastes. As a result, while more states may adopt EPA’s universal waste rule, there is also a potential for each state to adopt more stringent requirements, such as bans on landfill or sewage disposal of pharmaceutical wastes, supplemental manifesting requirements, sourceseparation mandates, and additional requirements for waste reduction, minimization, recordkeeping, and emergency management procedures. State professional licensing boards, in particular pharmacy and medical boards, may also elect to enhance inspection and facility management requirements in response to EPA’s regulatory initiatives. EPA’s Proposed Changes for Disposing of Hazardous Pharmaceutical Wastes The EPA has proposed expanding the “universal waste rule” to include the disposal of hazardous pharmaceutical wastes. The EPA adopted the universal waste rule in 1995 to provide an optional streamlined and simplified set of requirements for managing certain types of hazardous waste typically generated in small quantities by a very large number of generators. Currently the universal waste rule applies to batteries, pesticides, mercury-containing equipment, and fluorescent, high intensity, neon, mercury vapor, high pressure sodium, metal halide or other types of lamps (called “universal wastes”). Generally, disposing of universal wastes may be a little less complicated than complying with the disposal requirements for hazardous pharmaceutical waste even though universal waste disposal is restricted to facilities permitted for the processing or disposal of hazardous wastes. In fact, generators who accumulate less than 5,000 kilograms (or approximately 11,000 pounds) of universal waste are not required to register with the EPA as hazardous waste generators. These generators may also arrange for the transportation of universal waste without compliance with hazardous waste manifesting requirements, and are not required to consider the volumes of materials handled as universal wastes in the SQGs or CESQG calculations when a facility also generates other types of hazardous wastes. In addition, if all wastes that fall within a category of materials classified as universal wastes are managed in compliance with universal waste standards, generators are not required to conduct assessments to determine whether particular materials constitute hazardous versus non-hazardous wastes. Small quantity “handlers” of universal waste, however, must generally limit the period of time universal wastes are stored on-site to not more than one year; comply with employee safety, labeling and record keeping requirements for the storage of universal wastes; and establish procedures to ensure that universal wastes are only processed and disposed of by other universal or hazardous waste management facilities. In its proposal, the EPA has suggested designating pharmaceutical wastes as an additional category of universal waste without any significant modifications of the existing requirements for the management of universal wastes. For purposes of the proposed expansion to the universal waste rule, “pharmaceuticals” consist of chemical products, vaccines or allergenics, or products primarily used to dispense or deliver chemical products, vaccines or allergenics, that do not contain a radioactive component, and are intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease or injury in man or other animals, or that affect the structure or function of the body in man or other animals. This definition includes products such as transdermal patches and oral delivery devices such as gums or lozenges, but excludes sharps, infectious or biohazardous waste, dental amalgams, December 2008 | 3 Health Care Alert medical devices not used for delivery or dispensing purposes. If adopted, the proposed expansion of the universal waste rule will give healthcare facilities and other facilities handling pharmaceutical waste, including reverse distributors, the option of managing pharmaceutical wastes through LQG, SWG or CESQG standards, or as universal wastes. In particular, the proposed rule would require healthcare facilities electing to handle pharmaceutical waste as a type of universal waste to comply with the following requirements: Waste management. Handlers of universal wastes must manage these wastes in a manner that prevents release of the materials into the environment. Wastes must be packed into containers that are structurally sound and pose minimal risks of release through spills or leakage. The containers are not required to be closed because most pharmaceutical wastes would be unused and in the original package. Handlers must not store incompatible pharmaceutical wastes in the same container without evaluating whether the mixture of the materials will threaten human health or the environment. For example, handlers must determine whether the mixture will create an explosion or omit toxic mists, fumes, dusts or gases. Wastes may be sorted in a manner that complies with applicable OSHA regulations, but sorting is not required. Accumulation Limit. Pharmaceutical universal wastes handlers will be most likely classified as a small quantity universal waste handler, which allows the handler to accumulate 5,000 kg (11,000 lbs.) or less of any type of universal waste at any time. Accumulation Time Limits. There is a one year accumulation limit. For any accumulation beyond one year, the handler must demonstrate that accumulation is solely to facilitate proper recovery, treatment or disposal. Labeling. Pharmaceutical waste items or containers must be labeled either “Universal Waste – Pharmaceuticals,” or “Waste Pharmaceuticals.” Employee training. Employees must be familiar with proper waste handling and emergency procedures. Training that is provided under other programs that meet any or all of the requirements under the universal waste rule may be used to satisfy the requirements. Off-site shipments. Pharmaceutical universal wastes must be taken or sent to a place that is another universal waste handler, a destination facility or a foreign destination. Tracking universal waste shipments. Manifests are not required for shipments of universal wastes. Large quantity handlers of universal wastes must comply with basic tracking requirements under the universal waste rule. Comparison of the Current Disposal Requirements to the EPA’s Proposal The EPA’s proposed expansion of the universal waste rule to include pharmaceutical wastes may present an attractive alternative to complying with the current LQG and SQG standards. Notably, however, the question of whether the proposal offers practical benefit to CESQGs is less clear because of the costs associated with shipping pharmaceutical waste off-site for processing or disposal in compliance with universal waste standards. Such compliance will in most cases substantially exceed the costs of municipal waste disposal or commingling of pharmaceutical wastes with community sewage. On the other hand, the option to treat all pharmaceutical wastes as universal wastes without testing or evaluation may wholly or in part offset these costs for facilities otherwise subject to CESQG requirements because of the costs, difficulty and complexity of assessing whether particular streams of pharmaceutical waste are hazardous. EPA’s Rulemaking Process Regardless of the type of healthcare facility, the EPA’s proposal signals two very important things for all healthcare facilities – not just hospitals. First, healthcare facilities need to review the proposal to determine whether the expanded universal waste rule may be beneficial to them December 2008 | 4 Health Care Alert or whether more information is needed before they can make that determination. The EPA has also raised a number of questions regarding the proposal for which it has expressly requested comment. Given the influence the proposal, if adopted, might have on state regulation, healthcare facilities may want to provide such commentary. Questions and comments regarding the proposed expansion of the universal waste rule can be submitted to the EPA until February 9, 2009. Probably more important, however, is the clear message that the EPA is sending to all healthcare facilities that generate pharmaceutical waste – namely, complying with disposal requirements is simply not optional, and healthcare facilities that choose to ignore those requirements will pay a price. K&L Gates comprises multiple affiliated partnerships: a limited liability partnership with the full name K&L Gates LLP qualified in Delaware and maintaining offices throughout the U.S., in Berlin, in Beijing (K&L Gates LLP Beijing Representative Office), and in Shanghai (K&L Gates LLP Shanghai Representative Office); a limited liability partnership (also named K&L Gates LLP) incorporated in England and maintaining our London and Paris offices; a Taiwan general partnership (K&L Gates) which practices from our Taipei office; and a Hong Kong general partnership (K&L Gates, Solicitors) which practices from our Hong Kong office. K&L Gates maintains appropriate registrations in the jurisdictions in which its offices are located. A list of the partners in each entity is available for inspection at any K&L Gates office. This publication is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. ©1996-2008 K&L Gates LLP. All Rights Reserved. December 2008 | 5