Appellate, Constitutional and Governmental Litigation Alert Federal Appeals Court Holds Tribes Are

advertisement

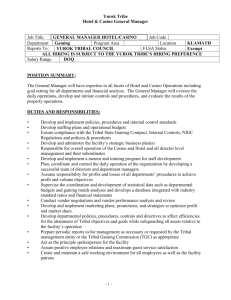

Appellate, Constitutional and Governmental Litigation Alert March 2007 Authors: Bart J. Freedman +1.206.270.7655 bart.freedman@klgates.com Linda J. Shorey +1.717.231.4510 linda.shorey@klgates.com K&L Gates comprises approximately 1,400 lawyers in 21 offices located in North America, Europe and Asia, and represents capital markets participants, entrepreneurs, growth and middle market companies, leading FORTUNE 100 and FTSE 100 global corporations and public sector entities. For more information, please visit www.klgates.com. www.klgates.com Federal Appeals Court Holds Tribes Are Subject to Federal Labor Law Tribal businesses operating on reservation land have traditionally been exempt from federal labor law. The inapplicability of federal labor law to tribes was recognized in the 1976 National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”) ruling, Fort Apache Timber Company, which held that a tribal government operating an on-reservation timber mill was not an “employer” within the meaning of the National Labor Relations Act (“NLRA”).1 Recently, however, in San Manuel Indian Bingo and Casino v. National Labor Relations Board, the federal Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit overruled Fort Apache to hold that Indian tribes running certain on-reservation businesses are now subject to the NLRA. This ruling, discussed in detail below, directly affects tribal casinos, which must now comply with federal labor regulations and submit to NLRB oversight. Tribal casinos may also, as a result of this ruling, experience an increase in unionization efforts directed at casino employees, most of whom are not currently unionized. The ruling is also of interest to the broader gaming community, which may see the increasing standardization of labor relations across the industry, as the NLRA is now uniformly applicable to both tribal and non-tribal casino enterprises. San Manuel Indian Bingo and Casino In San Manuel Indian Bingo and Casino, 2007 WL 420116 (D.C. Cir. February 9, 2007), the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians challenged an NLRB ruling that it had engaged in unfair labor practices in violation of the NLRA. The San Manuel tribe owns and operates a casino on their reservation in San Bernardino County, California that employs approximately 2,500 workers. The tribe regulates fair labor practices through its own tribal ordinances, as required by its gaming compact with the state of California. In 1999, the Hotel Employees & Restaurant Employees International Union (“HERE”) filed an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB, claiming that the San Manuel casino had denied it access to casino employees, while giving another union, the Communications Workers of America (“CWA”) preferential access. At the time HERE filed its charge, employees at the tribe’s casino were in the process of unionizing with CWA under the tribal labor ordinances. Applying the NLRA, the NLRB found that the casino had engaged in unfair labor practices and, in 2004, ordered the tribe to give HERE equal access to the casino. The tribe petitioned the federal court of appeals for review of the NLRB ruling, arguing that, under Fort Apache, the NLRA did not apply to tribal businesses on reservation land and the NLRB therefore had no jurisdictional basis to decide HERE’s claim. The Court of Appeals upheld the NLRB ruling in a decision that discussed the historical and legal nature of tribal sovereignty as well as more technical issues of statutory construction in the tribal context. The Court framed its analysis around two questions: 1) Would application of the NLRA to San Manuel’s casino violate federal Indian law by impinging upon protected tribal sovereignty? and 2) If the NLRA applies, does the term “employer” in the NLRA reasonably encompass Indian tribal governments operating commercial enterprises? 1. Fort Apache Timber Co., 226 N.L.R.B. 503 (1976). Appellate, Constitutional and Governmental Litigation Alert In answering the first question, the Court reasoned that tribal sovereignty is strongest where a tribe acts within its territorial borders to regulate purely internal matters and weakest where a tribe engages in off-reservation business activities with non-Indians. Within this framework, the San Manuel casino presented a hybrid circumstance. The casino itself is located on reservation land, is regulated by tribal ordinances and economically supports the tribal government. However, the casino is primarily operated as a commercial enterprise that employs non-Indians and markets to non-Indians living outside the reservation. The Court determined that the commercial aspects of the San Manuel casino far outweighed its governmental functions and held, therefore, that applying the NLRA to regulate labor relations at the casino would only minimally impinge on the tribe’s sovereignty. With respect to the second question – whether a tribe is an “employer” within the meaning of the NLRA – the Court recognized that the federal statute itself does not specifically define what constitutes an “employer.” Because Congress did not explicitly speak to this question when it enacted the NLRA, courts are required to defer to NLRB determinations on this issue and give “controlling weight” to “permissible” interpretations of the statute. Under this deferential standard of review, the Court held that the NLRB had reasonably interpreted the statute to find that, in its casino operations, the tribe constituted an “employer” within the meaning of NLRA. Conclusion The ultimate impact of the San Manuel decision remains to be seen. It is unclear, for instance, whether the decision will provide a basis for applying the NLRA to other types of tribal businesses that are more closely identified with a tribe’s governmental functions, like schools or health care facilities, or tribal businesses that employ and serve only tribal members. What is clear, however, is that San Manuel overturns the longstanding exemption of tribes from the requirements of the NLRA with respect to tribal casinos. It permits the NLRB to regulate labor relations within those casinos, irrespective of whether the tribe maintains its own labor ordinances or inconsistent decisions by other federal circuit courts. In the absence of this case reaching the Supreme Court of the United States on appeal of an inconsistent decision by a different federal circuit court, San Manuel governs and makes tribal casinos subject to NLRA regulations. In 2005, after the NLRB issued its ruling, Representative J.D. Hayworth of Arizona introduced “The Tribal Relations Restoration Act” (House Bill 16), which aimed restore the longstanding Fort Apache rule by amending the NLRA to add Indian tribes to the list of other governments exempt from the statute. The Act died in committee, and Hayworth lost re-election in 2006. It is unclear whether current legislators will introduce similar amendments to the NLRA. In the meantime, San Manuel governs and makes tribal casinos subject to NLRA regulations. K&L Gates comprises multiple affiliated partnerships: a limited liability partnership with the full name Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP qualified in Delaware and maintaining offices throughout the U.S., in Berlin, and in Beijing (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP Beijing Representative Office); a limited liability partnership (also named Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP) incorporated in England and maintaining our London office; a Taiwan general partnership (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis) which practices from our Taipei office; and a Hong Kong general partnership (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis, Solicitors) which practices from our Hong Kong office. K&L Gates maintains appropriate registrations in the jurisdictions in which its offices are located. A list of the partners in each entity is available for inspection at any K&L Gates office. This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. Data Protection Act 1998—We may contact you from time to time with information on Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP seminars and with our regular newsletters, which may be of interest to you. We will not provide your details to any third parties. Please e-mail london@klgates.com if you would prefer not to receive this information. ©1996-2007 Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP. All Rights Reserved. March 2007 |