Document 13691873

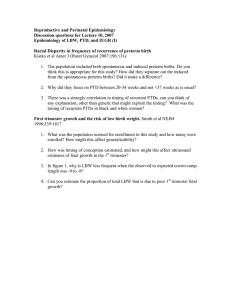

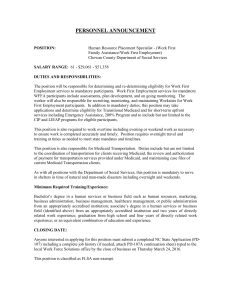

advertisement