Post-RYGB outcomes among those with and without current

advertisement

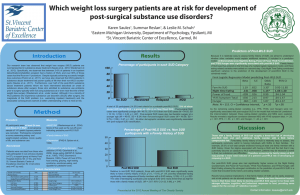

Post-RYGB outcomes among those with and without current substance use disorders: A matched controlled study. Melissa E. Pulcini1, Karen K. Saules1, & Leslie M. Schuh2 1 Eastern Michigan University, Department of Psychology, Ypsilanti, MI 2 St. Vincent Bariatric Center of Excellence, Carmel, IN Results Introduction Method Control group (cont) Measures Control participants (those with a history of RYGB but not postoperative SUDs) were recruited for the present study. Potential control participants were identified using a database from St. Vincent Bariatric Center of Excellence by matching with the SUDs participants on sex, age, and time since surgery. Quality of Life 2.69 (0.93) 3.46 (1.21) 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 * * * Postoperative SUD (controls only) World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test Version 3.0 (WHOASSIST V3.0) Control Group (n=26) 80.8% 96.2% 49.77 (8.09) 7.63 (2.97) 53.48 (8.74) Physical Psychological Social Domain 14.5 Environmental _____ 34.7% 34.6% 11.5% %EWL %Total body weight loss Surgical Failure 7.0 6 3 SUD group Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Prevalence Preliminary evidence suggests that RYGB surgery patients may be at an elevated risk for SUD during the postoperative period (e.g., King et al., 2012; Saules et al., 2010). As the number of bariatric surgery patients increase, so does this postoperative SUD subpopulation and the importance of understanding the nature of its weight loss and psychosocial outcomes, as well as its unique treatment needs. Following bariatric surgery, patients find themselves abruptly confronted with an inability to eat, but perhaps limited resources for managing food urges through other means, which can create conditions that foster drug and/or alcohol dependence. The present study found that post-RYGB patients in inpatient treatment for SUDs fared at least as well as post-RYGB controls in regard to weight loss but evidenced poorer quality of life and greater symptoms of depression. ______________________ * 9 0 38.2% Discussion 12 Note. * p= .001. 66.5% Note. * p=.048. Depression 15 74.4% * Global rating item 2: How satisfied are you with your health? * 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Control group _ 4.31 (0.84) Depressive Symptoms Patient Health Questionnaire- 9 (PHQ-9; Spitzer et al., 1999) Participant characteristics Gender (% female) Race (% White) Age Time since Surgery (yrs) Preoperative BMI (kg/m²) 2.62 (1.20) World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) SUD Group (n=26) 80.8% 92.3% 48.04 (8.31) 6.76 (2.76) 54.29 (12.02) Control group Note. Data are presented as M (SD). Global rating items range from scores of 1 through 5, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Transformed domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. * p<.05. Depression Control group SUD group __ Data from a previous study (Saules et. al., 2010) were used. Briefly, inpatients with one or more SUDs being treated at a substance abuse treatment facility in Brighton, Michigan were screened for a history of RYGB during a routine medical interview upon intake. Interested individuals with a history of RYGB were recruited into the study. Control Group (n=26) Global rating item 1: How would you rate your quality of life? * __ SUD group Matched individuals were contacted about the study via postal mail. Those endorsing problematic substance use during the postoperative period were excluded from the analyses. SUD Group (n=26) Mean PHQ-9 score Procedures and Recruitment SUD group Mean scores of WHOQOL-BREF global items and transformed domains _ The present study compared questionnaire data from 26 SUD inpatients with a history of RYGB surgery with data from 26 controls with a history of RYGB surgery and absence of problematic postoperative substance use. For closer group comparison, controls were matched on three variables that have been linked to weight loss, depression, and/or quality of life outcomes in RYGB patients: sex, age, and time lapse since surgery. Differences between the SUD and control groups in mean %EWL (74.4±22.1 vs. 66.5±27.6, respectively) and mean percent total body weight change (-38.2±11.8 vs. -34.7±15.0, respectively) were not statistically significant. Members of the control group were, however, more likely to meet surgical failure criteria than members of the SUD group. Surgical failure was defined as < 50 %EWL. Quality of Life Mean score Our work suggests that post-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) patients are overrepresented in the inpatient substance abuse treatment population (Saules et al., 2010). However, little is known about how the surgical outcomes of these individuals differ from RYGB patients who do not experience substance use disorders (SUD) in the postoperative period. Weight Loss Control group Twenty-two of the 26 individuals (84.6%) in the SUD group met the PHQ-9 10+ point criteria for probable MDD, compared with five out of the 26 (19.2%) control participants. The difference in frequency between groups was significant, X2 (1, 52) = 22.3, p< .001. Expectation for improvement in quality of life is a common reason for seeking bariatric surgery (Munoz et al., 2007). The present study has shown that SUD is associated with poorer quality of life among post-RYGB patients. Bariatric surgery candidates should be educated on conditions that compromise postoperative quality of life, as well as the risk factors for, and likelihood of, developing these conditions. Contrary to the present study’s weight loss findings, a recent study of a community sample of post-bariatric surgery patients found that the presence of postoperative SUD predicted poorer weight loss and that this effect persisted after controlling for eating-related variables (Reslan, Saules, & Schuh, 2012). It is possible that this discrepancy may be due to the likely attenuation of SUD severity of individuals in the community sample relative to that of individuals in the present study. The appetite suppression effect of chronic substance use may be greater in those with more severe SUDs. Future research is needed to clarify the relationship between weight loss and SUD in the postoperative period. PostPres Presented at the 2012 Annual Meeting of The Obesity Society Contact information: mpulcini@emich.edu