Which weight loss surgery patients are at risk for development... post-surgical substance use disorders?

advertisement

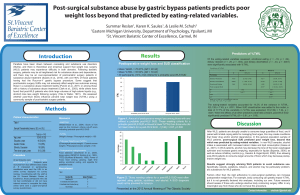

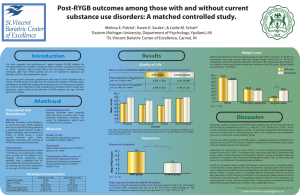

Which weight loss surgery patients are at risk for development of post-surgical substance use disorders? Karen Saules1, Summar Reslan1, & Leslie M. Schuh2 1 Eastern Michigan University, Department of Psychology, Ypsilanti, MI 2 St. Vincent Bariatric Center of Excellence, Carmel, IN Results Introduction Our research team has observed that weight loss surgery (WLS) patients are overrepresented in substance abuse treatment (Saules et al., 2010; Wiedemann et al., 2012). Specifically, we observed that between 2-6% of patients in an inpatient detoxification/rehabilition program had a history of WLS, and over 90% of those cases had the Roux-en-Y procedure. Despite typically achieving successful weight loss outcomes (Pulcini et al., 2011), we have also observed that WLS patients in substance abuse treatment had poorer quality of life than their non-WLS counterparts (Saules et al., 2011). Furthermore, over half of the post-WLS substance abuse treatment patients whom we have interviewed described an onset of substance abuse after surgery; those who admitted to substance use problems prior to surgery typically were not using substances at or even near the time of their weight loss surgery (Wiedemann et al., under review). Although it is a minority of WLS patients who experience substance use disorders (SUDs) after surgery, the magnitude of the SUD problem (i.e., warranting inpatient treatment) and the associated consequences warrant a better understanding of who is most at risk. Procedure Measures All participants were at least 24 mos post-Roux-en-Y WLS. A convenience sample of 141 gastric bypass patients was recruited. Participants completed a survey assessing eating- and weight-related variables, mood, quality of life, and substance use. ~MAST/AD (Westermeyer et al., 2004): Score of five used as the cut-off score indicating probable post-WLS SUD Patients were recruited from those who had participated in our previous studies (n=37), a support group at Henry Ford Hospital (Detroit, MI; n=15), and from St. Vincent Bariatric Center of Excellence (Carmel, IN; n=42 online and n=47 by mail). ~Family History of SUD ~Depression (PHQ-9; Spitzer et al., 1999), ~Postoperative eating-behavior: Food addiction (YFAS; Gearhardt et al., 2009), binge eating (QEWP-R; Spitzer et al., 1993), TFEQ (Stunkard & Messick, 1985), Power of Food (PFS), food craving, grazing, night eating syndrome, emotional eating, and appetite for palatable foods. 79% 72.2% 27.8% 47.8% 12.3% 29.7% 10.1% Age (M ± SD) Race (% White) Education (M ± SD) 53.4 ± 10.3 93% 14.5 ± 2.6 Surgery Age Years Since Surgery % Roux-en-Y Excess Weight Loss Total Weight Loss 47.0 ± 10.0 yrs 6.2 ± 2.7 yrs 100% 70.7% (± 22.3%) 35.5% (± 10.4%) Because it is relatively easy to assess family history of SUD, we aimed to understand whether other variables would explain additional variance, if included in a prediction model. At the bivariate level, Nightime Eating, Power of Food, YFAS Food Addiction, and TFEQ Hunger were significantly associated with post-WLS SUD. Family history of SUD was thus entered on the first step of a multiple logistic regression model, and these eating-related variables were added on a second step. Only Night Time Eating contributed significant variance to the prediction of the development of post-WLS SUD in the combined model Percentage of participants in each SUD Category 80 Final Logistic Regression Model predicting Post-WLS SUD Beta S.E Odds 95% CI Ratio Fam Hx SUD 1.19 .652 3.30† 0.92-11.85 Night time Eating .141 .058 1.15* 1.03-1.30 Power of Food -.009 .026 0.99 .94-1.04 YFAS Symptom Total -.030 .213 0.97 .64-1.47 Hunger .063 .129 1.07 .83-1.37 Note. N = 115. CI = Confidence interval, † p <.10 *p <.05 60 40 20 0 No SUD Recovered Relapsed NOU Percentage of Post-WLS SUD vs. Non SUD participants with a Family History of SUD 50 Patient characteristics Gender (% Female) Marital Status Married/Live with partner Single/Divorced/Widowed Employment Status Full time Part time Retired/Disabled Unemployed/Student 100 A total of 20 participants (14.3%) met criteria for a probable post-WLS SUD, 70% of whom denied SUD before WLS -- a group we refer to as New Onset SUD. Post-surgical SUD cases were significantly younger (M = 46.70, SD = 8.91) than non-SUD cases (M = 54.55, SD = 10.15), t (134) = 3.25, p = .001. Post-surgical SUD cases also had bariatric surgery at a younger age (M = 40.05, SD = 8.34) than non-post-surgical SUD cases (M = 48.09, SD = 9.79), t (139) = 3.47, p = .001. No other demographic variables were significantly associated with post-surgical SUD classification. Method Recruitment Predictors of Post-WLS SUD 40 30 20 10 0 Post-WLS SUD Non SUD Relative to non-SUD WLS patients, those with post-WLS SUD were significantly more likely to have a family history of SUD, χ2 (1), = 4.18, p= .04, and they endorsed having significantly more categories of family members with a SUD history, t (139) = 2.3, p =.023. The odds of developing a probable post-surgical SUD were nearly three times as high for those with a family history of SUD, OR = 2.67; 95% CI [1.02, 6.99], p = .046. Presented at the 2012 Annual Meeting of The Obesity Society Following bariatric surgery, patients find themselves abruptly confronted with an inability to eat, but perhaps limited resources for managing food urges through other means, which can create conditions that foster drug and/or alcohol dependence. As the remaining eating-related variables (i.e., PFS, YFAS, and Hunger) were not significantly associated with post-surgical SUD in the model that included all predictors, the intercorrelation between these eating-related variables and NEQ were explored. Results revealed a significant correlation between NEQ with YFAS symptom total, r = .29, p = .001, PFS, r = .53, p = .001, and Hunger, r = .42, p = .001. Discussion Following bariatric surgery, patients find themselves abruptly confronted with an inability to eat, but perhaps limited resources for managing food urges through other means, which can create conditions that foster drug and/or alcohol dependence. Those with a family history of SUD had roughly a three-fold risk of developing post-WLS SUD, and each additional family member with a SUD history compounded risk. Fortunately, family history of SUD is relatively easy to assess, and participants commonly admit to having individuals with SUDs in their families. For example, 29.3% of our total sample endorsed having at least one family member with a SUD history. Given the stigma associated with having a SUD and the fact that it may potentially become an obstacle to WLS authorization, patients may be reluctant to admit to their own substance use difficulties. Therefore, screening for family history of SUD may provide a more valid indicator of a patient’s post-WLS risk of developing or relapsing to a SUD. Our post-WLS SUD group also had significantly higher scores on the Night Eating Questionnaire, the Power of Food Scale, YFAS Food Addiction, and TFEQ Hunger, with Night Eating showing the strongest contribution to the prediction of post-WLS SUD in a model that included family history and eating-related variables. Results have practical implications in that family history of SUD can be easily assessed, and at-risk patients can be advised accordingly. Results also have theoretical implications in that those most likely to develop post-WLS SUD appear to be those with stronger affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses to food, providing some support for the concept of “addiction transfer.” Contact information: ksaules@emich.edu