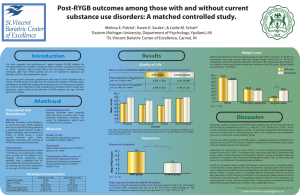

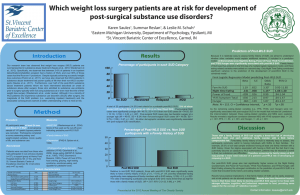

Introduction Methods Results

advertisement

Post-surgical substance abuse by gastric bypass patients predicts poor weight loss beyond that predicted by eating-related variables. Summar Reslan1, Karen K. Saules1, & Leslie M. Schuh2 1 Eastern Michigan University, Department of Psychology, Ypsilanti, MI 2 St. Vincent Bariatric Center of Excellence, Carmel, IN Predictors of %TWL Results Introduction Posttoperative weight loss and SUD classification Predictors of %TWL • Mean %EWL = 70.67% (SD = 22.34) • Mean %TWL = 35.54% (SD = 10.43) • 20 participants (14%) met criteria for a probable post-WLS SUD Model 1 Dietary Restraint Dietary Disinhibition 35 Emotional Eating 30 15 Sample Characteristics [mean ± SD, or n (%)] Age, years Education, years Gender: Female Ethnicity: Caucasian Time since surgery, years Total (n = 141) 53.40 (10.33) 14.50 (2.61) 112 (79%) 130 (93%) 6.13 (2.69) Procedure All participants were at least 24 months post-Roux-en-Y WLS. Subjects were recruited from four different sites (Table 2). If interested in participating, candidates were sent the URL to an online survey deployed via survey monkey. Coordinating with the staff at the St. Vincent Bariatric Center of Excellence, those participants who did not feel comfortable or did not have internet access to complete the study online were sent a paper-and-pencil survey questionnaire. Measures ~MAST/AD (Westermeyer et al., 2004): Score of five used as the minimum criteria cut-off score indicating probable post-WLS SUD ~%Excess Weight loss (%EWL) ((Presurgical excess weight - Current excess weight) / Presurgical excess weight) x 100. ~Postoperative eating-behavior Food addiction (Gearhardt et al., 2009), binge eating (QEWP-R; Spitzer et al., 1993), TFEQ (Stunkard & Messick, 1985), Power of Food, food craving, grazing, night time eating, emotional eating, and appetite for palatable foods. Probable post-WLS SUD 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Recruitment Table 2 Recruitment Site General Survey Link St. Vincent Bariatric Center of Excellence (online) St. Vincent Bariatric Center of Excellence (Hard-copy) Henry Ford Hospital Number of Participants 37 42 47 15 [0.08, 0.77] [-1.50, -0.33] .044 [-0.06, 0.14] .045 [-0.05, 0.14] -5.61* [-10.24, -0.97] .142 .177 7.49*** 7.24*** ∆R2 .035 ∆F 5.73* The eating-related variables accounted for 14.2% of the variance in %TWL, F(3,139) = 7.49, p = .0001. When SUD classification was added to the model, a total of 17.7% of the variability in %TWL was explained, F(4,139) = 7.24, p = .0001. When the effects of all other predictors were held constant, post-WLS SUD significantly predicted %TWL (B = -5.61, p = .018). No post-WLS SUD Figure 1. Amount of postoperative weight loss among those with and without a probable post-WLS SUD. Those meeting criteria for a probable post-WLS SUD achieved a lower %TWL than those who did not meet criteria for a post-WLS SUD , t (138) = 2.67, p=.009 ~%TWL (Weight change / Presurgical weight) x 100 .421* -.918** Note. N = 139. CI = Confidence interval. *p <.05, **p < .01, *** p < .001 5 Percentage Table 1 [0.05, 0.75] [-1.59, -0.41] F 10 Patient characteristics .403* R2 20 0 95% CI B -.998** Post-surgical SUD 25 Methods Model 2 95% CI B Variables 40 %TWL • Parallels have been drawn between overeating and substance use disorders (SUDs), and there is theoretical and empirical support that weight loss surgery • (WLS) patients may experience difficulty in both domains. Following might bariatric • s, oncologists surgery, patients may be at heightened risk for substance abuse and dependence, and • there may be an over-representation of post-bariatric surgery patients in substance abuse treatment (Saules et postal., 2010), with over 90% of those patients having had the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure. Some suggest that • post-bariatric surgery SUDs may not adversely affect weight loss outcomes among • in a substance abuse treatment facility (Pulcini et al., 2011) or among those those before with a history of substance abuse treatment (Clark et al., 2003), while others have found that post-WLS patients who drink large volumes of high-calorie liquids (e.g., • alcohol) lose less weight following surgery (Yale & Weiler, 1991). We assessed • whether post-WLS SUDs influence percent total weight loss (%TWL) using a community sample of post-bariatric surgery patients. Of the eating-related variables assessed, emotional eating (r = -.16, p = .04), dietary restraint (r = .25, p = .003), and dietary disinhibition (r = -.33, p = .0001) were significantly associated with %TWL. Figure 2. Those meeting criteria for a post-WLS SUD most often reported using opioids, sedatives, and alcohol. A SUD diagnosis could not be provided for tobacco. Presented at the 2012 Annual Meeting of The Obesity Society Following bariatric surgery, patients find themselves abruptly confronted with an inability to eat, but perhaps limited resources for managing food urges through other means, which can create conditions that foster drug and/or alcohol dependence. Discussion • WLS, patients are abruptly unable to consume large quantities of food, and if After paired with limited coping skills for managing food urges, this may create conditions that foster drug and/or alcohol dependence. In this general population sample of • WLS patients, post-surgical SUD predicted poor weight loss, beyond that • was predicted by eating-related variables. In non-WLS samples, alcohol which intake is associated with increased caloric intake and lipid consumption (Kesse et al., 2001). In WLS patients, alcohol may decrease the tone of the lower esophageal • sphincter and increase gastric emptying, especially for liquids (Bujanda, 2000), as well as reduce inhibitory control (e.g., Easdon post- & Vogel-Sprott, 2000), thus allowing post-WLS patients to consume larger amounts of food, which may decrease postop• erative weight loss. Following bariatric surgery, patients find themselves abruptly confronted with an inability to eat, but perhaps limited resources for managing food urges through other means, which can create conditions that foster drug and/or alcohol dependence. Results suggest strongly advising WLS patients to avoid substance use. • Specifically, opioids, sedatives, tobacco, and alcohol may be particularly problematic substances for WLS patients. Factors other • than the rigid adherence to post-surgical guidelines can increase postoperative weight loss. For example, body contouring can greatly impact %TWL, • generally factored into analyses, including our own. Future research but it is not should assess if those who undergo elective body contouring surgery differ in any meaningful way from those who do not have this procedure. Contact information: shabhab1@emich.edu